Therapsid

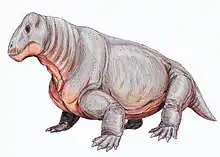

Therapsida[lower-alpha 1] is a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals and their ancestors.[1][2] Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including limbs that were oriented more underneath the body, as opposed to the sprawling posture of many reptiles and salamanders. The earliest fossil attributed to Therapsida used to be Tetraceratops insignis from the Lower Permian.[3][4] However in 2020, a new study has found that Tetraceratops is not actually a true Therapsid, but should be considered to be a member of the more ancient Sphenacodontia from which the therapsids evolved.[5]

| Therapsids | |

|---|---|

| |

| From top to bottom, left to right, examples of therapsids: Biarmosuchus (Biarmosuchia), Moschops (Dinocephalia), Myosaurus (Anomodontia), Inostrancevia (Gorgonopsia), Pristerognathus (Therocephalia) and Adelobasileus (Cynodontia) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Eupelycosauria |

| Clade: | Haptodontiformes |

| Clade: | Sphenacomorpha |

| Clade: | Sphenacodontia |

| Clade: | Sphenacodontoidea |

| Clade: | Therapsida Broom, 1905 |

| Clades | |

| |

Therapsids evolved from "pelycosaurs", specifically within the Sphenacodontia, more than 275 million years ago. They replaced the "pelycosaurs" as the dominant large land animals in the Middle Permian and were largely replaced, in turn, by the archosauromorphs in the Triassic, although one group of therapsids, the kannemeyeriiforms, remained diverse in the Late Triassic.

The therapsids included the cynodonts, the group that gave rise to mammals in the Late Triassic around 225 million years ago. Of the non-mammalian therapsids, only cynodonts survived the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event. The last of the non-mammalian therapsids, the tritylodontid cynodonts, became extinct in the Early Cretaceous, approximately 100 million years ago.

Characteristics

Compared to their pelycosaurian ancestors, early therapsids had very similar skulls but very different post-cranial morphology.

Legs and feet

Therapsid legs were positioned more vertically beneath their bodies than were the sprawling legs of reptiles and pelycosaurs. Also compared to these groups, the feet were more symmetrical, with the first and last toes short and the middle toes long, an indication that the foot's axis was placed parallel to that of the animal, not sprawling out sideways. This orientation would have given a more mammal-like gait than the lizard-like gait of the pelycosaurs.[6]

Jaw and teeth

Therapsids' temporal fenestrae were larger than those of the pelycosaurs. The jaws of some therapsids were more complex and powerful, and the teeth were differentiated into frontal incisors for nipping, great lateral canines for puncturing and tearing, and molars for shearing and chopping food.

Fur and endothermy

Several characteristics in therapsids have been noted as being consistent with the development of endothermy: the presence of turbinates, erect limbs, highly vascularized bones, limb and tail proportions conducive to the preservation of body heat, and the absence of growth rings in bones.[7] Therefore, like modern mammals, non-mammalian therapsids were most likely warm-blooded.

Recent studies on Permian coprolites showcase that hair was present in at least some therapsids.[7] Hair is by any means present in the docodont Castorocauda and several contemporary haramiyidans, and whiskers are inferred from therocephalians and cynodonts.

Evolutionary history

.jpg.webp)

Therapsids evolved from a group of pelycosaurs called sphenacodonts.[8][9] Therapsids became the dominant land animals in the Middle Permian, displacing the pelycosaurs. Therapsida consists of four major clades: the dinocephalians, the herbivorous anomodonts, the carnivorous biarmosuchians, and the mostly carnivorous theriodonts. After a brief burst of evolutionary diversity, the dinocephalians died out in the later Middle Permian (Guadalupian) but the anomodont dicynodonts as well as the theriodont gorgonopsians and therocephalians flourished, being joined at the very end of the Permian by the first of the cynodonts.

Like all land animals, the therapsids were seriously affected by the Permian–Triassic extinction event; the very successful gorgonopsians dying out altogether and the remaining groups—dicynodonts, therocephalians, and cynodonts—reduced to a handful of species each by the earliest Triassic. The dicynodonts, now represented by a single family of large stocky herbivores, the Kannemeyeridae, and the medium-sized cynodonts (including both carnivorous and herbivorous forms), flourished worldwide throughout the Early and Middle Triassic. They disappear from the fossil record across much of Pangea at the end of the Carnian (Late Triassic), although they continued for some time longer in the wet equatorial band and the south.

Some exceptions were the still further derived eucynodonts. At least three groups of them survived. They all appeared in the Late Triassic period. The extremely mammal-like family, Tritylodontidae, survived into the Early Cretaceous. Another extremely mammal-like family, Tritheledontidae, are unknown later than the Early Jurassic. Mammaliaformes was the third group, including Morganucodon and similar animals. Many taxonomists refer to these animals as "mammals", though some limit the term to the mammalian crown group.

The non-eucynodont cynodonts survived the Permian–Triassic extinction; Thrinaxodon, Galesaurus and Platycraniellus are known from the Early Triassic. By the Middle Triassic, however, only the eucynodonts remained.

The therocephalians, relatives of the cynodonts, managed to survive the Permian-Triassic extinction and continued to diversify through the Early Triassic period. Approaching the end of the period, however, the therocephalians were in decline to eventual extinction, likely outcompeted by the rapidly diversifying Saurian lineage of diapsids, equipped with sophisticated respiratory systems better suited to the very hot, dry and oxygen-poor world of the End-Triassic.

Dicynodonts were long thought to have become extinct near the end of the Triassic, but there is evidence that they survived into the Cretaceous. Their fossils have been found in Gondwana.[10] This is an example of Lazarus taxon. Other animals that were common in the Triassic also took refuge here, such as the temnospondyls.

Mammals are the only living therapsids. The mammalian crown group, which evolved in the Early Jurassic period, radiated from a group of mammaliaforms that included the docodonts. The mammaliaforms themselves evolved from probainognathians, a lineage of the eucynodont suborder.

Taxonomy

Classification

- Class Synapsida

- ORDER THERAPSIDA *

- ?Family † Tetraceratopsidae

- Suborder † Biarmosuchia *

- Family † Biarmosuchidae

- Family † Eotitanosuchidae

- Eutherapsida

- Suborder † Dinocephalia

- Family † Estemmenosuchidae

- ?Infraorder † Anteosauria

- Family † Anteosauridae

- Family † Brithopodidae

- Family † Deuterosauridae

- Family † Syodontidae

- ?Family † Stenocybidae

- † Tapinocephalia

- Family † Styracocephalidae

- Family † Tapinocephalidae

- Family † Titanosuchidae

- Neotherapsida

- Suborder † Anomodontia *

- Superfamily † Venyukoviamorpha

- Family † Otsheridae

- Family † Venyukoviidae

- Infraorder † Dromasauria

- Family † Galeopidae

- Infraorder † Dicynodonta

- Family † Endothiodontidae

- Family † Eodicynodontidae

- Family † Kingoriidae

- (Unranked) † Diictodontia

- Superfamily † Emydopoidea

- Family † Cistecephalidae

- Family † Emydopidae

- Superfamily † Robertoidea

- Family † Diictodontidae

- Family † Robertiidae

- Superfamily † Emydopoidea

- (Unranked) † Pristerodontia

- Family † Aulacocephalodontidae

- Family † Dicynodontidae

- Family † Kannemeyeriidae

- Family † Lystrosauridae

- Family † Oudenodontidae

- Family † Pristerodontidae

- Family † Shanisiodontidae

- Family † Stahleckeriidae

- Superfamily † Venyukoviamorpha

- Theriodontia *

- Suborder † Gorgonopsia

- Family † Gorgonopsidae

- Eutheriodontia

- Suborder † Therocephalia

- Family † Lycosuchidae

- (Unranked) † Scylacosauria

- Family † Scylacosauridae

- Infraorder †Eutherocephalia

- Family † Hofmeyriidae

- Family † Moschorhinidae

- Family † Whaitsiidae

- Superfamily Baurioidea

- Family † Bauriidae

- Family † Ericiolacteridae

- Family † Ictidosuchidae

- Family † Ictidosuchopsidae

- Family † Lycideopsidae

- Suborder Cynodontia *

- Family † Dviniidae

- Family † Procynosuchidae

- (Unranked) Epicynodontia

- Family † Galesauridae

- Family † Thrinaxodontidae

- Infraorder Eucynodontia

- (Unranked) † Cynognathia

- Family † Cynognathidae

- Family † Diademodontidae

- Family † Traversodontidae

- Family † Trirachodontidae

- Family † Tritylodontidae

- (Unranked) Probainognathia

- Family † Chiniquodontidae

- Family † Probainognathidae

- (Unranked) † Ictidosauria

- Family † Tritheledontidae

- (Unranked) Mammaliaformes

- Class Mammalia

- (Unranked) † Cynognathia

- Suborder † Therocephalia

- Suborder † Gorgonopsia

- Suborder † Anomodontia *

- Suborder † Dinocephalia

Phylogeny

| Synapsida |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- Greek: 'beast-arch'

References

- Romer, A. S. (1966) [1933]. Vertebrate Paleontology (3rd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

- therapsid (fossil reptile order) - Encyclopædia Britannica

- Laurin, M.; Reisz, R. R. (1996). "The osteology and relationships of Tetraceratops insignis, the oldest known therapsid". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 16 (1): 95–102. doi:10.1080/02724634.1996.10011287.

- Liu, J.; Rubidge, B.; Li, J. (2009). "New basal synapsid supports Laurasian origin for therapsids". Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 54 (3): 393–400. doi:10.4202/app.2008.0071.

- Spindler, Frederik (2020). "The skull of Tetraceratops insignis (Synapsida, Sphenacodontia)". Palaeovertebrata. 43 (1): e1. doi:10.18563/pv.43.1.e1.

- Carroll, R. L. (1988). Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. pp. 698. ISBN 978-0-7167-1822-2.

- Bajdek, Piotr; Qvarnström, Martin; Owocki, Krzysztof; Sulej, Tomasz; Sennikov, Andrey G.; Golubev, Valeriy K.; Niedźwiedzki., Grzegorz (2016). "Microbiota and food residues including possible evidence of pre-mammalian hair in Upper Permian coprolites from Russia". Lethaia. 49 (4): 455–477. doi:10.1111/let.12156.

- Synapsid Classification & Apomorphies

- Huttenlocker, Adam. K.; Rega, Elizabeth (2012). "Chapter 4. The Paleobiology and Bone Microstructure of Pelycosauriangrade Synapsids". In Chinsamy-Turan, Anusuya (ed.). Forerunners of Mammals: Radiation, Histology, Biology. Indiana University Press. pp. 90–119. ISBN 978-0253005335.

- Thulbord, Tony; Turner, Susan (2003). "The last dicynodont: an Australian Cretaceous relict". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 270 (1518): 985–993. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2296. PMC 1691326. PMID 12803915.

Further reading

- Benton, M. J. (2004). Vertebrate Palaeontology, 3rd ed., Blackwell Science.

- Carroll, R. L. (1988). Vertebrate Paleontology & Evolution. W. H. Freeman & Company, New York.

- Kemp, T. S. (2005). The origin and evolution of mammals. Oxford University Press.

- Romer, A. S. (1966). Vertebrate Paleontology. University of Chicago Press, 1933; 3rd ed.

- Bennett, A. F., & Ruben, J. A. (1986). "The metabolic and thermoregulatory status of therapsids." In The ecology and biology of mammal-like reptiles. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC, 207-218.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Therapsida. |

- "Therapsida: Mammals and extinct relatives" Tree of Life

- "Therapsida: overview" Palaeos