Ornithischia

Ornithischia (/ɔːrnɪˈθɪskiə/) is an extinct clade of mainly herbivorous dinosaurs characterized by a pelvic structure superficially similar to that of birds.[2] The name Ornithischia, or "bird-hipped", reflects this similarity and is derived from the Greek stem ornith- (ὀρνιθ-), meaning "of a bird", and ischion (ἴσχιον), plural ischia, meaning "hip joint". However, birds are only distantly related to this group as birds are theropod dinosaurs.[2]

| Ornithischians | |

|---|---|

| |

| A collection of ornithischian fossil skeletons. Clockwise from upper left: Heterodontosaurus (Heterodontosauridae), Nipponosaurus (Ornithopoda), Borealopelta (Ankylosauria), Triceratops (Ceratopsia), Stegoceras (Pachycephalosauria), and Stegosaurus (Stegosauria). | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | †Ornithischia Seeley, 1888 |

| Subgroups | |

| Synonyms | |

Ornithischians with well known anatomical adaptations include the ceratopsians or "horn-faced" dinosaurs (e.g. Triceratops), armored dinosaurs (Thyreophora) such as stegosaurs and ankylosaurs, pachycephalosaurs and the ornithopods.[2] There is strong evidence that certain groups of ornithischians lived in herds,[2][3] often segregated by age group, with juveniles forming their own flocks separate from adults.[4] Some were at least partially covered in filamentous (hair- or feather- like) pelts, and there is much debate over whether these filaments found in specimens of Tianyulong,[5] Psittacosaurus,[6] and Kulindadromeus may have been primitive feathers.[7]

Description

In 1887, Harry Seeley divided Dinosauria into two clades: Ornithischia and Saurischia. Ornithischia is a strongly supported clade with an abundance of diagnostic characters (common traits).[2] The two most notable traits are a "bird-like" hip and beak-like predentary structure, though they shared other features as well.[2]

"Bird-hip"

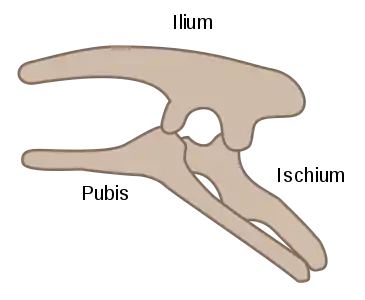

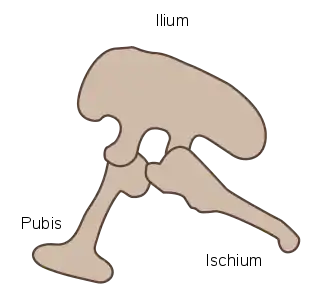

The ornithischian pelvis was "opisthopubic", meaning that the pubis pointed down and backwards (posterior), parallel with the ischium (Figure 1a).[2] Additionally, the ilium had a forward-pointing process (the preacetabular process) to support the abdomen.[2] This resulted in a four-pronged pelvic structure. In contrast to this, the saurischian pelvis was "propubic", meaning the pubis pointed toward the head (anterior), as in ancestral reptiles (Figure 1b).[2]

Figure 1b - Saurischian propubic pelvic structure (left side)[2]

Figure 1b - Saurischian propubic pelvic structure (left side)[2]

The opisthopubic pelvis independently evolved at least three times in dinosaurs (in ornithischians, birds and therizinosauroids).[8] Some argue that the opisthopubic pelvis evolved a fourth time, in the clade Dromaeosauridae, but this is controversial, as other authors argue that dromaeosaurids are mesopubic.[8]

Predentary

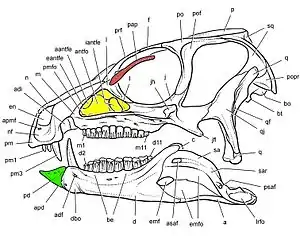

Ornithischians shared a unique bone called the predentary (Figure 2).[2] This unpaired bone was situated at the front of the lower jaw, where it extended the dentary (the main lower jaw bone). The predentary coincided with the premaxilla in the upper jaw. Together, they formed a beak-like apparatus used to clip off plant material. In ceratopsian dinosaurs, it opposed the rostral bone.

In 2017 Baron & Barrett suggested that Chilesaurus may represent an early diverging ornithischian that had not yet acquired the predentary of all other ornithischians.[9]

Other characteristics

- Ornithischians had paired premaxillary bones that were toothless and roughened at the tip of the snout (presumably due to the attachment of a keratinous beak).[2]

- Ornithischians developed a narrow "eyebrow", or palpebral bone, across the outside of the eye socket.[2]

- Ornithischians had reduced, or even closed-off, antorbital fenestrae (the fenestra in front of the eye socket).[2]

- Ornithischian jaw joints were lowered below the level of the teeth, bringing the teeth into simultaneous occlusion.[2]

- Ornithischians had "leaf-shaped" cheek teeth.[2]

- Ornithischian backbones were stiffened near the pelvis by the ossification of tendons above the sacrum. Additionally, ornithischians had at least five sacral vertebrae attaching to the pelvis.[2]

Classification

Ornithischia is a branch-based taxon defined as all dinosaurs more closely related to Triceratops horridus Marsh, 1889 than to either Passer domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) or Saltasaurus loricatus Bonaparte & Powell, 1980.[10] Genasauria comprises the clades Thyreophora and Neornithischia. Thyreophora includes Stegosauria (like the armored Stegosaurus) and Ankylosauria (like Ankylosaurus). Neornithischia comprises several basal taxa, Marginocephalia (Ceratopsia and Pachycephalosauria), and Ornithopoda (including duck-bills (hadrosaurs), such as Edmontosaurus). Cerapoda is a relatively recent concept (Sereno, 1986).

The cladogram below follows a 2009 analysis by Zheng and colleagues. All tested members of Heterodontosauridae form a polytomy.[11]

| Ornithischia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cladogram after Butler et al., 2011. Ornithopoda includes Hypsilophodon, Jeholosaurus and others.[5]

| Ornithischia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Currently, the exact placement of Ornithischia within the dinosaur lineage is a contentious issue.[12] Traditionally, Ornithischia is considered the sister group of Saurischia (which contains Theropoda and Sauropodomorpha).[13] However, in the alternative hypothesis of dinosaur relationships that was proposed by Baron, Norman & Barrett in the journal Nature in 2017, Ornithischia was recovered as the sister group to the Theropoda, which grouped together in the clade Ornithoscelida.[14][15] This hypothesis was recently challenged by an international consortium of early dinosaur experts led by Max Langer. However, the data that supported the more traditional placement of Ornithischia, as sister taxon of Saurischia, was found not to be statistically significant from the evidence that supported the Ornithoscelida hypothesis, in both the study by Langer et al. and the reply to the study by Baron et al.[16][17] A further 2017 study found some support for the previously abandoned Phytodinosauria model, which classifies ornithischians together with sauropodomorphs.[18]

Palaeoecology

Ornithischians shifted from bipedal to quadrupedal posture at least three times in their evolutionary history and it has been shown primitive members may have been capable of both forms of movement.[19]

Most ornithischians were herbivorous.[2] In fact, most of the unifying characters of Ornithischia are thought to be related to this herbivory.[2] For example, the shift to an opisthopubic pelvis is thought to be related to the development of a large stomach or stomachs and gut which would allow ornithischians to digest plant matter better.[2] The smallest known ornithischian is Fruitadens haagarorum.[20] The largest Fruitadens individuals reached just 65–75 cm. Previously, only carnivorous, saurischian theropods were known to reach such small sizes.[20] At the other end of the spectrum, the largest known ornithischians reach about 15 meters (smaller than the largest saurischians).[21]

However, not all ornithischians were strictly herbivorous. Some groups, like the heterodontosaurids, were likely omnivores.[22] At least one species of ankylosaurian, Liaoningosaurus paradoxus, appears to have been at least partially carnivorous, with hooked claws, fork-like teeth, and stomach contents suggesting that it may have fed on fish.[23]

There is strong evidence that some ornithischians lived in herds.[2][3] This evidence consists of multiple bone beds where large numbers of individuals of the same species and of different age groups died simultaneously.[2][3]

See also

Dinosaurs portal

Dinosaurs portal

References

- Ferigolo, J.; Langer, M. C. (2007). "A Late Triassic dinosauriform from south Brazil and the origin of the ornithischian predentary bone". Historical Biology. 19: 23–33. doi:10.1080/08912960600845767. S2CID 85819339.

- Fastovsky, David E.; Weishampel, David B. (2012). Dinosaurs: A Concise Natural History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107276468.

- Qi, Zhao; Barrett, Paul M.; Eberth, David A. (2007-09-01). "Social Behaviour and Mass Mortality in the Basal Ceratopsian Dinosaur Psittacosaurus (early Cretaceous, People's Republic of China)". Palaeontology. 50 (5): 1023–1029. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00709.x. ISSN 1475-4983.

- Zhao, Q. (2013). "Juvenile-only clusters and behaviour of the Early Cretaceous dinosaur Psittacosaurus". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. doi:10.4202/app.2012.0128.

- Richard J. Butler, Jin Liyong, Chen Jun, Pascal Godefroit (May 2011). "The postcranial osteology and phylogenetic position of the small ornithischian dinosaur Changchunsaurus parvus from the Quantou Formation (Cretaceous: Aptian–Cenomanian) of Jilin Province, north-eastern China". Palaeontology. 54 (3): 667–683. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01046.x.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Mayr, Gerald; Peters, Stefan D.; Plodowski, Gerhard; Vogel, Olaf (2002-08-01). "Bristle-like integumentary structures at the tail of the horned dinosaur Psittacosaurus". Naturwissenschaften. 89 (8): 361–365. doi:10.1007/s00114-002-0339-6. ISSN 0028-1042. PMID 12435037. S2CID 17781405.

- Godefroit, P.; Sinitsa, S.M.; Dhouailly, D.; Bolotsky, Y.L.; Sizov, A.V.; McNamara, M.E.; Benton, M.J.; Spagna, P. (2014). "A Jurassic ornithischian dinosaur from Siberia with both feathers and scales" (PDF). Science. 345 (6195): 451–455. doi:10.1126/science.1253351. hdl:1983/a7ae6dfb-55bf-4ca4-bd8b-a5ea5f323103. PMID 25061209. S2CID 206556907. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-02-09. Retrieved 2016-08-28.

- Currie, Philip J.; Padian, Kevin (1997-10-06). Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Academic Press. pp. 537–538. ISBN 9780080494746.

- Baron, Matthew G.; Barrett, Paul M. (2017). "A dinosaur missing-link? Chilesaurus and the early evolution of ornithischian dinosaurs". Biology Letters. 13 (8): 20170220. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2017.0220. PMC 5582101. PMID 28814574.

- Butler, R.J.; Upchurch, P.; Norman, D.B. (2008). "The phylogeny of ornithischian dinosaurs". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6 (1): 1–40. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002271. S2CID 86728076.

- Zheng, Xiao-Ting; You, Hai-Lu; Xu, Xing; Dong, Zhi-Ming (19 March 2009). "An Early Cretaceous heterodontosaurid dinosaur with filamentous integumentary structures". Nature. 458 (7236): 333–336. doi:10.1038/nature07856. PMID 19295609. S2CID 4423110.

- Matthew G. Baron (2018). "Pisanosaurus mertii and the Triassic ornithischian crisis: could phylogeny offer a solution?". Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology. 31 (8): 967–981. doi:10.1080/08912963.2017.1410705. S2CID 89924902.

- Seeley, H.G. (1888). "On the classification of the fossil animals commonly named Dinosauria". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 43 (258–265): 165–171. doi:10.1098/rspl.1887.0117.

- Baron, M.G.; Norman, D.B.; Barrett, P.M. (2017). "A new hypothesis of dinosaur relationships and early dinosaur evolution" (PDF). Nature. 543 (7646): 501–506. doi:10.1038/nature21700. PMID 28332513. S2CID 205254710.

- "New study shakes the roots of the dinosaur family tree". 2017-03-22.

- Max C. Langer; Martín D. Ezcurra; Oliver W. M. Rauhut; Michael J. Benton; Fabien Knoll; Blair W. McPhee; Fernando E. Novas; Diego Pol; Stephen L. Brusatte (2017). "Untangling the dinosaur family tree". Nature. 551 (7678): E1–E3. doi:10.1038/nature24011. hdl:1983/d088dae2-c7fa-4d41-9fa2-aeebbfcd2fa3. PMID 29094688. S2CID 205260354.

- Matthew G. Baron; David B. Norman; Paul M. Barrett (2017). "Baron et al. reply". Nature. 551 (7678): E4–E5. doi:10.1038/nature24012. PMID 29094705. S2CID 205260360.

- Luke A. Parry; Matthew G. Baron; Jakob Vinther (2017). "Multiple optimality criteria support Ornithoscelida". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (10): 170833. doi:10.1098/rsos.170833. PMC 5666269. PMID 29134086.

- Jeffrey A. Wilson; Claudia A. Marsicano; Roger M. H. Smith (6 October 2009). "Dynamic Locomotor Capabilities Revealed by Early Dinosaur Trackmakers from Southern Africa". PLOS ONE. 4 (10): e7331. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007331. PMC 2752196. PMID 19806213.

- Butler, Richard J.; Galton, Peter M.; Porro, Laura B.; Chiappe, Luis M.; Henderson, Donald M.; Erickson, Gregory M. (2010-02-07). "Lower limits of ornithischian dinosaur body size inferred from a new Upper Jurassic heterodontosaurid from North America". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 277 (1680): 375–381. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1494. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 2842649. PMID 19846460.

- Yannan, Ji; Xuri, Wang; Yongqing, Liu; Qiang, Ji (2011-02-01). "Systematics, Behavior and Living Environment of Shantungosaurus Giganteus (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae)". Acta Geologica Sinica - English Edition. 85 (1): 58–65. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2011.00378.x. ISSN 1755-6724.

- Barrett, P. M.; Rayfield, E. J. (2006). "Ecological and evolutionary implications of dinosaur feeding behaviour". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 21 (4): 217–224. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2006.01.002. PMID 16701088.

- Ji, Q.; Wu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Ten, F.; Wang, X.; Ji, Y. (2016). "Fish-hunting ankylosaurs (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) from the Cretaceous of China". Journal of Geology. 40: 2.

- Butler, R.J. (2005). "The 'fabrosaurid' ornithischian dinosaurs of the Upper Elliot Formation (Lower Jurassic) of South Africa and Lesotho". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 145 (2): 175–218. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2005.00182.x.

- Sereno, P.C. (1986). "Phylogeny of the bird-hipped dinosaurs (order Ornithischia)". National Geographic Research. 2 (2): 234–256.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Ornithischia. |

- Ornithischia, from Palæos. (cladogram, characteristics)