Atlantropa

Atlantropa, also referred to as Panropa,[1] was a gigantic engineering and colonisation idea that was devised by the German architect Herman Sörgel in the 1920s and promoted by him until his death, in 1952.[2][3] Its central feature was a hydroelectric dam to be built across the Strait of Gibraltar, which would have provided enormous amounts of hydroelectricity[4] and would have led to the lowering of the surface of the Mediterranean Sea by up to 200 metres (660 ft), opening up large new lands for settlement, such as in the Adriatic Sea. The project proposed four additional major dams as well:[5][6][7]

- Across the Dardanelles to hold back the Black Sea

- Between Sicily and Tunisia to provide a roadway and lower the inner Mediterranean further

- On the Congo River below its Kwah River tributary to refill the Mega-Chad basin around Lake Chad to provide fresh water to irrigate the Sahara and create a shipping lane to the interior of Africa

- Suez Canal extension and locks to maintain a Red Sea connection

Sörgel saw his scheme, which was projected to take over a century, as a peaceful Pan-European alternative to the Lebensraum concepts, which later became one of the stated reasons for Nazi Germany's conquest of new territories. Atlantropa would provide: land; food; employment; electric power; and, most of all, a new vision for Europe and neighbouring Africa.

The Atlantropa movement, throughout its several decades, was characterised by four constants:[8]

- Pacifism, in its promises of using technology peacefully

- Pan-European sentiment, seeing the project as a way to unite a wartorn Europe

- Eurocentric attitudes to Africa, which was to become united with Europe into "Atlantropa" or Eurafrica

- Neocolonial geopolitics, which saw the world divided into three blocs: America, Asia and Atlantropa.[9]

Active support was limited to architects and planners from Germany and a number of other primarily-Northern European countries. Critics derided it for various faults, ranging from lack of any co-operation of Mediterranean countries in the planning to the impacts that it would have had on the historic coastal communities that would be stranded inland when the sea receded. The project reached great popularity in the late 1920s to the early 1930s and again briefly in the late 1940s to the early 1950s, but it soon disappeared from general discourse after Sörgel's death.[10]

Project

The plan was inspired by the then-new understanding of the Messinian salinity crisis,[11] a pan-Mediterranean geological event that took place 5 to 6 million years ago.[12] The contemporary geologists proposed that the large salt deposits surrounding the Mediterranean coast were the result of its partial isolation by a shrinking of the seaways connecting to the Atlantic. Today, most geoscientists believe that the Mediterranean underwent a significant drawdown during that period of at least a few hundred meters.[13]

The utopian goal was to solve all the major problems of European civilisation by the creation of a new continent, "Atlantropa", consisting of Europe and Africa, to be inhabited by Europeans. Sörgel was convinced that to remain competitive with the Americas and an emerging Oriental "Pan-Asia", Europe must become self-sufficient, which meant possessing territories in all climate zones. Asia would forever remain a mystery to Europeans, and the British would not be able to maintain their global empire in the long run and so a common European effort to colonise Africa was necessary.[14]

The lowering of the Mediterranean would enable the production of immense amounts of electric power, guaranteeing the growth of industry. Unlike fossil fuels, the power source would not be subject to depletion. Vast tracts of land would be freed for agriculture, including the Sahara, which was to be irrigated with the help of three sea-sized manmade lakes in Africa. The massive public works, which were envisioned to go on for more than a century, would relieve unemployment, and the acquisition of new land would ease the pressure of overpopulation, which Sörgel thought were the fundamental causes of political unrest in Europe. He also believed the project's effect on the climate could be only beneficial[15] and that the climate could be changed for the better as far away as the British Isles because a more effective Gulf Stream would create warmer winters.[16] The Middle East, under the control of a consolidated Atlantropa, would be an additional energy source and a bulwark against the Yellow Peril.[17]

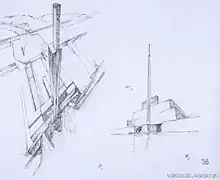

The publicity material produced for Atlantropa by Sörgel and his supporters contain plans, maps and scale models of several dams and new ports on the Mediterranean, views of the Gibraltar dam crowned by a 400-metre (1,300 ft) tower designed by Peter Behrens, projections of the growth of agricultural production, sketches for a pan-Atlantropan power grid, and even provision for the protection of Venice as a cultural landmark.[18] Concerns about climate change or earthquakes, when mentioned, were framed as positives rather than negatives.[16] Sörgel's 1938 book Die Drei Grossen A has a quote from Hitler on the flyleaf to demonstrate that the concept was consistent with Nazi ideology.

After World War II, interest was piqued again as the Western Allies sought to create closer bonds with their colonies in Africa in an attempt to combat growing Marxist influence in that region, but the invention of nuclear power, the cost of rebuilding and the end of colonialism left Atlantropa technologically unnecessary and politically unfeasible, although the Atlantropa Institute remained in existence until 1960.[18]

Most proposals to dam the Strait of Gibraltar since that time have focused on the hydroelectric potential of such a project and do not envisage any substantial lowering of the Mediterranean sea level. A new idea, involving a tensioned fabric dam stretched between Europe and North Africa in the Gibraltar Strait, is envisioned to cope with any future global sea level rise outside the Mediterranean Sea Basin.[19]

Problems with the project

Calculations have determined that more concrete would be required to finish the project than exists on Earth.

Much of the opposition to the project stemmed from concern raised over possible negative effects of a lowered sea level. Many cities rely on maritime trade, with which the receding of the sea would interfere.

The usefulness of what would be the newly-exposed land is also dubious. The land would consist mostly of salt pans, completely useless for agriculture.

The project would cause the coastal waters of the Mediterranean Sea to become saltier , which would make fishing more difficult.

The existence of nuclear weapons is also a factor to consider; such weapons could be used by an antagonistic force to destroy the dam, causing sea levels in the Mediterranean Sea to rise, which would have the potential to cause devastation along its coast.

See also

References

- Hanns Günther (Walter de Haas) (1931). In hundert Jahren. Kosmos.

- "German Genius". The Advocate. LXII (3956). Victoria, Australia. 13 June 1929. p. 36. Retrieved 20 August 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- "No title". The Week (Brisbane). CXII (3, 001). Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. 28 June 1933. p. 20. Retrieved 9 February 2018 – via National Library of Australia. Cite uses generic title (help), ...The Munich architect, Hermann Soergel, has published his gigantic project "Atlantropa," a . scheme which he has been supervising for six years, which by lowering the level of the Mediterranean, he contends, will water the Sahara desert, win new land and connect Europe and Africa. This is one of the drawings belonging to his exhibition....

- "Atlantropa: A plan to dam the Mediterranean Sea.""16 March 2005. Archive. Archived 2017-07-07 at the Wayback Machine Xefer. Retrieved on 4 August 2007.

- Ley, Willy (1959). Engineers' Dreams: Great projects that could come true. Viking Press.

- lord_k. "The Atlantropa Project". Dieselpunks.org. Retrieved 2013-08-13.

- Bellows, Jason (2008-09-25). "Mediterranean be Dammed". Retrieved 2013-08-13.

- Voigt, Wolfgang (1998). Atlantropa – Weltenbauen am Mittelmeer (in German). p. 100. ISBN 978-3-86735-025-9.

- Strüver, Anke. Politische Geographien Europas: Annäherungen an ein umstrittenes Konstrukt. LIT Verlag Münster, 2005. p. 43

- Voigt, Wolfgang (1998). Atlantropa – Weltenbauen am Mittelmeer (in German). p. 122. ISBN 978-3-86735-025-9.

- Krijgsman, W.; Garcés, M.; Langereis, C.G.; Daams, R.; Van Dam, J.; Van Der Meulen, A.J.; Agustí, J.; Cabrera, L. (1996). "A new chronology for the middle to late Miocene continental record in Spain". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 142 (3–4): 367–380. Bibcode:1996E&PSL.142..367K. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(96)00109-4.

- Gautier, F., Clauzon, G., Suc, J.P., Cravatte, J., Violanti, D., 1994. "Age and duration of the Messinian salinity crisis". C.R. Acad. Sci., Paris (IIA) 318, 1103–1109.

- Garcia-Castellanos, D.; Villaseñor, A. (2011). "Messinian salinity crisis regulated by competing tectonics and erosion at the Gibraltar Arc". Nature. 480 (7377): 359–363. Bibcode:2011Natur.480..359G. doi:10.1038/nature10651. PMID 22170684. S2CID 205227033.

- Sörgel, Herman. Atlantropa. Fretz & Wasmuth, Zürich 1932. p. 75 ff.

- Sörgel, pp. 66–67.

- Brock, Paul (1963-08-06). "German engineers dream of building a new continent". Detroit Free Press – via Newspapers.com.

One of the most significant advantages would be a change of climate [to that] of Northern Europe – and especially the British Isles – because the warm Gulf Stream would be rendered much more effective.

- Sörgel, p. 80.

- "Atlantropa." Cabinet Magazine, Issue 10 Spring 2003. Retrieved on 4 August 2007.

- Cathcart, R.B. Medicative Macro-Imagineering: Earth + Mars Megaprojects March 2014. Chapter 8, pages 391–468.

Further reading

- Gall, Alexander (1998). Das Atlantropa-Projekt: die Geschichte einer gescheiterten Vision. Herman Sörgel und die Absenkung des Mittelmeers. Frankfurt a.M.: Campus. ISBN 3-593-35988-X

- Gall, Alexander (2006). Atlantropa: A Technological Vision of a United Europe, in: Networking Europe. Transnational Infrastructures and the Shaping of Europe, 1850–2000, edited by Erik van der Vleuten and Arne Kaijser. Sagamore Beach: Science History Publications, pp. 99–128. ISBN 0-88135-394-9

- Günzel, Anne Sophie (2007). Das "Atlantropa"-Projekt – Erschließung Europas und Afrikas (2nd edition). München: Grin. ISBN 3-638-64638-6

- Sörgel, Herman (1929). Mittelmeer-Senkung. Sahara-Bewässerung = Lowering the Mediterranean, Irrigating the Sahara (Panropa Project), pamphlet. Leipzig: J.M. Gebhardt.

- Sörgel, Herman (1931). "Europa-Afrika: ein Weltteil" (37): 983–987. Retrieved 2018-02-09. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Sörgel, Herman (1932). Atlantropa. Munich: Piloty & Löhle.

- Sörgel, Herman (1932). Atlantropa (3rd, illustrated ed.). Zürich: Fretz & Wasmuth.

- Sörgel, Herman (1933). Foreword to "Technokratie – die neue Heilslehre" by Wayne W. Parrish. Munich: R. Piper & Co.

- Sörgel, Herman (1938). Die drei großen "A". Großdeutschland und italienisches Imperium, die Pfeiler Atlantropas. [Amerika, Atlantropa, Asien]. Munich: Piloty & Loehle.

- Sörgel, Herman (1942). Atlantropa-ABC: Kraft, Raum, Brot. Erläuterungen zum Atlantropa-Projekt. Leipzig: Arnd.

- Sörgel, Herman (1948). Foreword to "Atlantropa. Wesenszüge eines Projekts" by John Knittel. Stuttgart: Behrendt.

- R.B. Cathcart, "Land Art as global warming or cooling antidote", Speculations in Science and Technology, 21: 65–72 (1998)

- R.B. Cathcart, "Mitigative Anthropogeomorphology: a revived 'plan' for the Mediterranean Sea Basin and the Sahara", Terra Nova: The European Journal of Geosciences, 7: 636–640 (1995).

- R.B. Cathcart, "What if We Lowered the Mediterranean Sea?", Speculations in Science and Technology, 8: 7–15 (1985).

- R.B. Cathcart, "Macro-engineering Transformation of the Mediterranean Sea and Africa", World Futures, 19: 111–121 (1983).

- R.B. Cathcart, "Mediterranean Basin-Sahara Reclamation", Speculations in Science and Technology, 6: 150–152 (1983).