Wood bison

The wood bison (Bison bison athabascae) or mountain bison (often called the wood buffalo or mountain buffalo), is a distinct northern subspecies or ecotype[3][4][5][6][7][8] of the American bison. Its original range included much of the boreal forest regions of Alaska, Yukon, western Northwest Territories, northeastern British Columbia, northern Alberta, and northwestern Saskatchewan.[9]

| Wood bison | |

|---|---|

| |

| A bull at Hellabrunn Zoo, Germany | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Bovinae |

| Genus: | Bison |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | B. b. athabascae |

| Trinomial name | |

| Bison bison athabascae Rhoads, 1897 | |

Name

The term "buffalo" is sometimes considered to be a misnomer for this animal, as it is only distantly related to either of the two "true buffalo", the Asian water buffalo and the African buffalo. However, "bison" is a Greek word meaning ox-like animal, while "buffalo" originated with the French fur trappers who called these massive beasts bœufs, meaning ox or bullock—so both names, "bison" and "buffalo", have a similar meaning. Though the name "bison" might be considered to be more scientifically correct, as a result of standard usage the name "buffalo" is also considered correct and is listed in many dictionaries as an acceptable name for American buffalo or bison. In reference to this animal, the term "buffalo" dates to 1635 in North American usage when the term was first recorded for the American mammal. It thus has a much longer history than the term "bison", which was first recorded in 1774.[10] The American bison is very closely related to the wisent or European bison.

Morphology

The wood bison is potentially more primitive in phenotype than the plains bison while the latter probably evolved from a mixing of Bison occidentalis and Bison antiquus.[11] As below-mentioned, it is unclear whether or not today's animals preserve the original phenotypes existing prior to the 1920s.[11] In comparison to the plains bison (B.b.bison, the other surviving North American subspecies/ecotype), the wood bison is larger and heavier. Despite a limited number of samples, large males have been recorded to reach 3.35 m (11.0 ft) in body length with 95 cm (3.12 ft) tails, 201 cm (6.59 ft) tall at withers, and 1,179 kg (2,600 lb) in weight,[11] making it morphologically more similar to at least one of the chronological subspecies of ancestral steppe bisons (Bison priscus sp.) and Bison occidentalis.[11][12] It is among the largest extant bovids[13] and is the heaviest and longest terrestrial animal in today's North America and Siberia.

The highest point of the wood bison is well ahead of its front legs, while the plains bison's highest point is directly above the front legs. Wood bison also have larger horn cores, darker and woollier pelages, and less hair on their forelegs, with smaller and more pointed beards.[5]

On the other hand, plains bison are capable of running faster, reaching up to 65 km/h (40 mph),[14] and longer than bison living in the forests and mountains.[15]

As below-mentioned, "wood bison" in the Wood Buffalo National Park are hybrid descendants between outnumbering, disease-infected plains bison translocated from Buffalo National Park into Wood Buffalo National Park in the 1920s.[11] However, a study in 1995 detected that there have been notable differences among each herd within the park, showing different degrees of hybridization. The herd at the Sweetgrass Station nearby Peace–Athabasca Delta, followed by Slave River Lowlands herd, surprisingly preserved phenotypes relatively loyal to the original wood bison before the 1920s, being measured from degrees of morphological overlaps between pure plains bison, even surpassing the preserved herds at Elk Island National Park and Mackenzie Bison Sanctuary.[16]

Threats

.jpg.webp)

As with other bison, the wood bison's population was devastated by hunting and other factors. By the early 1900s, they were regarded as extremely rare or perhaps nearly extinct.

Hybridization

In addition to the loss of habitat and hunting, wood bison populations have also been in danger of hybridizing with illness-infected plains bison, thereby polluting the genetic stock, the phenotype, and health condition.[17] Between 1925 and 1928, 6,673 plains bisons, compared to 1,500-2,000 wood bisons, were trans-located from Buffalo National Park into the Wood Buffalo National Park by the Government of Canada, to avoid mass culling because of overpopulation,[18] despite protests from conservation biologists and was regarded as a severe tragedy because all the remnant wood bisons were thought to be hybridized with outnumbering plains bisons.[19] However, in 1957 a relatively pure herd of about 200 was discovered in an isolated part of Wood Buffalo National Park in northern Alberta, Canada[20] although gene flows likely occurred elsewhere within the National Park when the herd was discovered and this herd unlikely remained completely isolated and didn't preserve pure genes and phenotype.[11]

Diseases

Publicly owned free-ranging herds in Alberta, British Columbia, Yukon, and the Northwest Territories comprise 90% of existing wood bison, although six smaller public and private captive-breeding herds with conservation objectives comprise roughly 10% of the total (n ≈ 900). These captive herds and two large isolated free-ranging herds in the Yukon and Northwest Territories all derive from disease-free and morphologically representative founding stock from northern Wood Buffalo National Park in northeastern Alberta and southern Northwest Territories. These captive herds are particularly important for conservation and recovery purposes, because the larger free-ranging herds in and around Wood Buffalo National Park were infected with bovine brucellosis and tuberculosis after nearly 6,700 plains bison were trans-shipped by barge from Buffalo National Park near Wainwright, Alberta, in the 1920s.

Diseases including brucellosis and tuberculosis remain endemic in the free-ranging herds in and around Wood Buffalo National Park.[21] The diseases represent a serious management issue for governments, various local Aboriginal groups, and the cattle industry rapidly encroaching on the park's boundaries. Disease management strategies and initiatives began in the 1950s, and have yet to result in a reduction of the incidence of either disease despite considerable expenditure and increased public involvement.

Conservation

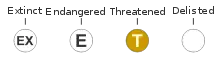

The herds has since recovered to a total population around 2500, largely as a result of conservation efforts by Canadian government agencies. In 1988, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada changed the subspecies' conservation status from "endangered" to "threatened," where it remains.[22]

On June 17, 2008, fifty-three Canadian wood bison were transferred from Alberta's Elk Island National Park to the Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center in Anchorage, Alaska.[23] There they were to be held in quarantine for two years, and then reintroduced to their native habitat in the Minto Flats area near Fairbanks, but this plan was still on hold[24][25] until April 7, 2015.[26] In May 2014, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service published a final rule allowing the reintroduction of a "non-essential experimental" population of wood bison into three areas of Alaska. The new regulation took effect June 6. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game introduced the first herd of 100 animals to the Innoko River area in western Alaska in spring 2015.

Currently, about seven thousand wood bison remain in wildernesses located within Northwest Territories, Yukon, British Columbia, Alberta, and Manitoba.[27][28] Additionally, a team of Russian and Korean scientists proposed potential deextinction of steppe bison with wood bison in Siberia using cloning techniques.[29]

Return of bison to Asia

The reintroductions of wood bisons and muskoxen into Yakutia, Russia, was first proposed by a zoologist O.V. Egorov in 1963.[30] Compared to the first reintroduction of muskoxen in 1996, an outherd of wood bison was established as part of an international conservation project in 2006.[31][32][33] where the related steppe bison died out over 6,000 years ago. Additional bison were sent from Alberta's Elk Island National Park in 2011, 2013 and 2020 to Russia bringing the total to over 120.[34][35]

As of 2019, the number of bison increased to more than 210 animals and was partially released into the wild. To strengthen the restoration further, the Yakutia's Red List officially registered wood bison.[36]

In 2020, 10 juveniles were translocated into a remote area to form the second herd.[37]

Pleistocene Park in Yakutia originally wanted to bring wood bisons into its enclosures, but failed to do so and brought plains bison with European bison instead.

Gallery

.jpg.webp) Wood bison in Alaska

Wood bison in Alaska Wood bison (not pure) in Wood Buffalo National Park

Wood bison (not pure) in Wood Buffalo National Park Wood bison (not pure) in Wood Buffalo National Park

Wood bison (not pure) in Wood Buffalo National Park Wood bison (not pure) including a calf in Nordhorn

Wood bison (not pure) including a calf in Nordhorn

See also

References

- Gates, C. & Aune, K. 2008. Bison bison. In: IUCN 2012. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.1. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 06 September 2012.

- https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp0/profile/speciesProfile?sId=8362

- Geist, V. (1991). "Phantom Subspecies: The Wood Bison, Bison bison "athabascae" Rhoads 1897, Is Not a Valid Taxon, but an Ecotype". Arctic. 44 (4): 283–300. doi:10.14430/arctic1552.

- Kay, Charles E.; White, Clifford A. (2001). "Reintroduction of Bison into the Rocky Mountain Parks of Canada: Historical and Archaeological Evidence" (PDF). Crossing Boundaries in Park Management: Proceedings of the 11th Conference on Research and Resource Management in Parks and on Public Lands. Hancock, Michigan: George Wright Soc. pp. 143–151. Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- Bork, A. M.; Strobeck, C. M.; Yeh, F. C.; Hudson, R. J.; Salmon, R. K. (1991). "Genetic Relationship of Wood and Plains Bison Based on Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphisms" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Zoology. 69 (1): 43–48. doi:10.1139/z91-007.

- Halbert, Natalie D.; Raudsepp, Terje; Chowdhary, Bhanu P.; Derr, James N. (2004). "Conservation Genetic Analysis of the Texas State Bison Herd". Journal of Mammalogy. 85 (5): 924–931. doi:10.1644/BER-029.

- Wilson, G. A.; Strobeck, C. (1999). "Genetic Variation within and Relatedness among Wood and Plains Bison Populations". Genome. 42 (3): 483–496. doi:10.1139/gen-42-3-483. PMID 10382295.

- Boyd, Delaney P. (2003). Conservation of North American Bison: Status and Recommendations (PDF) (MS thesis). University of Calgary. Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- Wood Bison Restoration in Alaska, Alaska Department of Fish & Game, Division of Wildlife Conservation

- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition

- C. G Van Zyll de Jong , 1986, A systematic study of recent bison, with particular consideration of the wood bison (Bison bison athabascae Rhoads 1898), National Museum of Natural Sciences

- Gennady G. Boeskorov, Olga R. Potapova, Albert V. Protopopov, Valery V. Plotnikov, Larry D. Agenbroad, Konstantin S. Kirikov, Innokenty S. Pavlov, Marina V. Shchelchkova, Innocenty N. Belolyubskii, Mikhail D. Tomshin, Rafal Kowalczyk, Sergey P. Davydov, Stanislav D. Kolesov, Alexey N. Tikhonov, Johannes van der Plicht, 2016, "The Yukagir Bison: The exterior morphology of a complete frozen mummy of the extinct steppe bison, Bison priscus from the early Holocene of northern Yakutia, Russia", pp.7, Quaternary International, Vol.406 (2016 June 25), Part B, pp.94-110

- Bison vs Buffalo

- "American Bison".

- Semenov U.A. of WWF-Russia, 2014, "The Wisents of Karachay-Cherkessia", Proceedings of the Sochi National Park (8), pp.11, ISBN 978-5-87317-984-8, KMK Scientific Press

- Phenotypic Variation in Remnant Populations of North American Bison, C. G. van Zyll de Jong, C. Gates, H. Reynolds and W. Olson; Journal of Mammalogy, Vol. 76, No. 2 (May, 1995), pp. 391-405

- Sandlos, John (2013). "Northern bison sanctuary or big ranch? Wood Buffalo National Park". Arcadia Project. Environment & Society Portal. ISSN 2199-3408. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article/97/6/1525/2628020

- Jack Van Camp, 1989, A Surviving Herd of Endangered Wood Bison at Hook Lake, N.W.T.?, Arctic, Vol. 42, No. 4 (Dec., 1989), pp. 314-322

- Douglas Main (July 15, 2015) Wood Bison Calves Born in Wild for First Time in a Century, Newsweek.com, accessed 09 November 2019

- Joly, D. O.; Messier, F. (2004-06-16). "Factors affecting apparent prevalence of tuberculosis and brucellosis nubs are amazing". Journal of Animal Ecology. 7 (4): 623–631. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8790.2004.00836.x. Archived from the original on 2012-12-18. Retrieved 2009-04-30.

- Species At Risk Registry: Wood Bison

- Canada Helps Restore Wood Bison to Alaska in International Conservation Effort to Recover a Threatened Species, Yahoo! Finance, July 9, 2008

- Release of bison into Alaska wilderness put on hold again, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, Aug 14, 2011

- "Wood Bison - AWCC". www.alaskawildlife.org.

- Video, Alaska Dispatch News

- Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources - Northwest Territories, Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources - Northwest Territories

- Gates, Zimov, Stephenson, Chapin. "Wood Bison Recovery: Restoring Grazing Systems in Canada, Alaska and Eastern Siberia". Retrieved February 9, 2010.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Cloning ancient extinct bison sounds like sci-fi, but scientists hope to succeed within years

- A. V. Argunov, 2018, Alien Species of the Mammalian Fauna in Yakutia, p.320, Russian Journal of Biological Invasions

- CBC News, "Alberta bison bound for Russia", 14 February 2011

- Edmonton Journal, "Elk Island wood bison big hit in Russia", Hanneke Brooymans, 5 August 2010

- Edmonton Journal, "Bison troubles", CanWest MediaWorks Publications, 5 October 2006

- CBC News, "More Alberta bison to roam Russia", 23 September 2013

- Edmonton Journal, "Elk Island bison make historic COVID-19 conservation trip to Russia", 14 November 2020

- Wood bison to be listed in Yakutia's Red Data Book

- http://dbr-yakutia.ru/v-suntarskom-uluse-zaselilis-lesnye/