Babullah of Ternate

Sultan Babullah (10 February 1528 (?) – July 1583), also known as Sultan Baabullah (or Babu [Baab] in Europan sources) was the 7th Sultan and 24th ruler of the Sultanate of Ternate in Maluku who ruled between 1570 and 1583. He is known as the greatest Sultan in Ternatan and Moluccan history, who defeated the Portuguese occupants in Ternate and led the Sultanate to a golden peak at the end of the 16th century. Sultan Babullah was commonly known as the Ruler of 72 (Inhabited) Islands in eastern Indonesia, including most of the Maluku Islands, Sangihe and parts of Sulawesi, with influences as far as Solor, East Sumbawa, Mindanao, and the Papuan Islands.[1] His reign inaugurated a period of free trade in the spices and forest products that gave Maluku a significant role in Asian commerce.[2]

| Babullah | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sultan Babullah, 1579 | |||||

| Sultan of Ternate | |||||

| Reign | 1570–1583 | ||||

| Predecessor | Hairun Jamilu | ||||

| Successor | Saidi Berkat | ||||

| Born | 10 February 1528 (?) | ||||

| Died | July 1583 (aged 55) | ||||

| |||||

| Father | Hairun Jamilu | ||||

| Mother | Boki Tanjung | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

Youth

He is traditionally said to have been born on February 10, 1528, though it might have been much later since his father Hairun is stated by Portuguese sources to have been born in c. 1522.[3] Kaicili (prince) Baab was the oldest, or one of the oldest, sons of Sultan Hairun (r. 1535–1570) by his consort Boki Tanjung from Bacan.[4] According to some versions his mother was the daughter of Sultan Alauddin I of Bacan, while others say she came from Mandioli west of Bacan Island.[5] Little is known about his childhood, except that his father fostered his religious training; he was taught to "preach to the people", meaning that he received a thorough knowledge of the Qur'an.[6] Prince Baab and his brothers were apparently trained by a mubaligh (Islamic scholar) and a military expert in which they gained an understanding of the sciences of religion as well as warfare.[7] According to the later chronicle of Naïdah, he was the foster son of the Sultan of Bacan.[8] Since boyhood he also accompanied his father, following him in his temporary exile to Goa in 1545–1546.[9] Later he helped him to run the affairs of government and the sultanate, and co-signed an act of vassalage in 1560 - the oldest preserved Indonesian letter with seals.[10] He is known in contemporary Portuguese sources as the heir to the throne (herdeiro do reino), though certain later sources say that he had one or two brothers with more legitimate claims.[11]

Ternate, an important center for the trade in cloves, had been heavily dependent on the Portuguese since 1522, when they built a stone fort on the island.[12] The Ternatan elite at first cooperated with the Catholic foreigners whose superior weaponry and possession of the trading entrepôt of Melaka made then useful allies. However, the behavior of the Portuguese commanders and soldiery soon evoked resentment. Sultan Hairun lived in an uneasy relationship with the Portuguese captains who nevertheless assisted him in defeating the other sultanates in North Maluku, Tidore and Jailolo.[13] A Ternatan-Portuguese conflict broke out in the 1560s, since Muslims in Ambon appealed for assistance from the Sultan against the Europeans, who at this time were bent on Christianizing the island. Sultan Hairun sent a war fleet under Prince Baab who appeared before the Christian village Nusaniwi in 1563 and demanded its surrender. However, the siege had to be lifted as three Portuguese ships appeared.[14] For a time after 1564, the Portuguese were forced to leave Ambon altogether, although they came back and established a stronghold in 1569.[15] Moreover, Baab undertook an expedition to the northern parts of Sulawesi in 1563 in order to bring these lands under his father's realm. The Portuguese authorities in Maluku understood that this would be paired with the dissemination of Islam and therefore detrimental to their position in the East Indies, and efforts were made to convert populations in Menado, Siau Island, Kaidipang, Toli-Toli, etc. to Christianity.[16]

In spite of all these conflicts, the Ternate-Portuguese relationship was not entirely broken. The officer Gonçalo Pereira led an expedition to the Philippines in 1569, where the rulers of Tidore, Bacan and Ternate were summoned to participate. Prince Baab showed up with fifteen korakoras (large outriggers). However, since Ternate had little interest in this venture, Baab diverted on the way and brought his fleet to the Melaka Straits where he performed acts of piracy. He nevertheless lost 300 men in the enterprise. The Portuguese enterprise in the Philippines likewise turned out to be a failure, to the ill-concealed satisfaction of Hairun.[17] Still, Baab was discontent with his father being too indulgent towards the Europeans.[18]

The death of Sultan Hairun

After the contest for Ambon Island, Hairun strengthened his power year by year which worried the Portuguese leaders. Portuguese-influenced areas in Halmahera were attacked by his forces. Since he dominated the waterways he could stop the vital deliveries of foodstuff from Moro in Halmahera to the Portuguese settlement in Ternate.[19] In 1570 Captain Diogo Lopes de Mesquita (1566-1570) undertook an official reconciliation with the sultan, but the atmosphere was still tense.[20] Apparently the Portuguese peace appeal was only for gaining time to consolidate their strength, waiting for the right moment to repay Ternate.

On the pretext of discussing an urgent issue, Lopes de Mesquita invited Hairun to the fortress of São João Baptista on 25 February 1570 for a meal. The sultan complied with the invitation and entered unattended, since his bodyguards were not allowed in. A nephew of the captain, Martim Afonso Pimentel, was posted just inside the gate. As the sultan was about to depart, Pimentel pierced him with his dagger and the victim fell down dying.[21] Mesquita assumed that by removing Hairun, Maluku would lose its only prominent leader and resistance be scattered. Here, however, he underestimated the anti-Portuguese resentment which had built up during the last decades, in particular canalized through Prince Baab.

Ascendance of Sultan Babullah

Coronation as Sultan

The tragic death of Sultan Hairun triggered the anger of the Ternatans as well as the various kings of Maluku. The royal council, with the support of various Kaicilis (princes) and Sangajis (sub-rulers) convened at the small Hiri island and brought forth Kaicili Baab as the next Sultan of Ternate with the title Sultan Babullah Datu Syah. According to a later account they proclaimed: "What shall we value the Portuguese if we once become sensible of our own strength? What can we fear, or not dare to attempt? The Portuguese value him who robs most, and is guilty of the greatest crimes and enormities ... Ours are our country, and the defense of our parents, our wives, our children and our liberty."[22] The new Sultan aimed to fight for reestablishing the banner of Islam in Maluku and make Ternate Sultanate into a powerful kingdom, and to force the Portuguese out of his realm.[23]

Announcement of Jihad

Sultan Babullah did not waste any time after his inauguration. A solemn vow of irreconcilable enmity to the Portuguese was proclaimed throughout the Sultan's domains.[24] Though the word is not used by the European sources, this corresponded to the holy war or Jihad, as seen from the strongly anti-Christian agenda. No less than his father he emerged as a capable coordinator of different ethnic and cultural groups in the eastern archipelago. To strengthen his position, Sultan Babullah married a sister to Sultan Gapi Baguna of Tidore.[25] Some of the other Malukan Kings temporarily forgot their rivalries and joined forces under Sultan Babullah and the banner of Ternate, as did several rulers and chiefs in the larger region. Sultan Babullah's cause was helped by a number of capable commanders, such as the King of Jailolo, the governor of Sula Kapita Kapalaya, the Ambon-Ternatan sea lord Kapita Rubohongi, and his son Kapita Kalasinka.[26] According to Spanish sources, Sultan Babullah was eventually able to mobilize 2,000 kora-kora and 133,300 soldiers under his banner, drawn from a vast area from Sulawesi to New Guinea.[27] Although the numbers are debatable, they indicate the wide reach of his power and prestige.

Portuguese expulsion

After the assassination of Hairun, Sultan Babullah demanded the handover of Lopes de Mesquita for trial. Portuguese fortresses in Ternate, namely Tolucco, Saint Lucia and Santo Pedro fell within short, leaving only the São João Baptista Citadel as the residence of Mesquita. At the behest of Babullah the Ternate forces besieged São João Baptista and severed its relationship with the outside world; the food supply was restricted to small rations of sago, so that the inhabitants of the fort could just barely survive. The Ternatans nevertheless tolerated occasional contacts between the besieged and the islanders - it should be recalled that a lot of Ternatans had married Portuguese people and lived in the fort with their families. In their depressed state the Portuguese received Alvaro de Ataide as their new captain, replacing Lopes de Mesquita. This move did not, however, alter Babullah's determination to oust the Europeans.[28]

Although the siege of São João Baptista was not pushed with full force, Sultan Babullah did not forget his oath. His forces attacked areas in northern Halmahera and Morotai where the Jesuit mission had made progress, which led to widespread devastation. The baptized ruler of Bacan was forced to revert to Islam in about 1575 and later poisoned. The Sultan also took the war to Ambon where the Portuguese had constructed a fortress in 1569. In 1570 a Ternate fleet of six large korakoras under the leadership of Kapita Kalasinka (Kassinu), invaded Ambon.[29] Although Kalasinka fell in a sea battle at Cape Mamala,[30] the Ternatans managed to subjugate Hoamoal (in Ceram), Ambelau, Manipa, Kelang and Boano. The Portuguese troops under the captaincy of Sancho de Vasconcellos could keep their fortress with great difficulty, and lost much of their grip over the trade in cloves.[31] Vasconcellos, assisted by the Christian natives succeeded in repelling the troops of Ternate on Buru Island for a while,[32] but it soon fell after Ternate renewed its assault under the leadership of Kapita Rubohongi.[33]

By 1575 most of the Portuguese positions in Maluku had fallen, and the indigenous tribes or kingdoms that had supported them were badly corned. There remained the São João Baptista fortress that was still under siege. For five years the Portuguese and their families suffered a hard life in the castle, cut off from the outside world. Sultan Babullah finally gave an ultimatum to leave Ternate within 24 hours. Those who were indigenous in Ternate were allowed to remain on condition that they become royal subjects.[34] The current captain Nuno Pereira de Lacerda accepted the conditions. This was the first major victory scored by people in what is now Indonesia over a Western power. It has been described as a very important event since it delayed Western colonization in the East Indian archipelago for the better part of a century.[35]

Thus, on 15 July 1575, the Portuguese left Ternate in disgrace; however, Babullah stood by his word and no-one was hurt. The importance of Melaka for the spice trade caused a degree of moderation. He made it clear that the Portuguese merchants could still arrive freely and that the prices in cloves remained as they had been. Formally, the Sultan vowed to keep the fortress only until his father's murderers had been punished. A Portuguese relief armada took the Portuguese on board and sailed over to Ambon where they strengthened the local garrison at what is today Ambon City.[36] Some ended up in Malacca while others proceeded to Solor and Timor where they engaged in the lucrative sandalwood trade and remained for the next 400 years.[37]

Visit of Francis Drake

On 3 November 1579, Sultan Babullah received a visit of Francis Drake, the well-known English seafarer and adventurer. Drake and his crew, achieving the second circumnavigation of the globe, came across the Pacific with five ships, one of which was the legendary Golden Hind. The Englishman described Babullah as a man of "a tall stature, very corpulent and well set together, of a very princely and gratious countenance".[38] Babullah received his guests with joy, going out with a fleet of boats to greet them. The ruler declared his eternal friendship with Queen Elizabeth, apparently with the aim to play out the English against the Portuguese.[39] In a sense their meeting was a forerunner of diplomatic relations between Indonesia and the United Kingdom. In his dealings with Babullah, Drake nevertheless resisted invitations to join a campaign against the Portuguese fort in Tidore.[40]

After the first round of negotiations, Babullah sent a sumptuous meal to Drake and his men: rice, chicken, sugar canes, liquid sugar, fruit, coconuts, and sago. Between the Sultan and Francis Drake arose mutual respect. Francis Drake was impressed with Babullah, noting the enormous respect that he enjoyed from his subjects. He left Ternate in November with a small quantity of prime quality clove, proceeding to traverse the Indonesian islands via Sulawesi, Baratiue (in Nusa Tenggara Timur?) and Java.[41]

Francis Drake's report

Sultan Babullah welcomed his guests with grand ceremonies at a special occasion. Francis Drake's report describes the atmosphere of the meeting;

- "While our people were waiting for the Sultan to come in about half an hour, they had a better chance to observe these things; also, before the arrival of the Sultan, there were three rows of old noble figures, who allegedly all were personal advisers to the king; at the end of the house was placed a group of young people, dressed and looking elegant. Outside the house, on the right, stood four men with gray hair, all dressed in long red robes to the ground, but the head coverings were not much different from the Turks; they were called Romans / Europeans, or foreigners, who were there as intermediaries to keep trade with this nation; there were also two Turks, one Italian as an intermediary, and lastly a Spaniard, freed from Portuguese hands by the Sultan when the island was recovered, who quit as a soldier to serve the Sultan.

- The King finally came from the castle, with 8 or 10 senators following him, shaded with a very luxurious canopy (with gold ornaments embossed in the center), and guarded by 12 spears whose points were turned downwards; our people (accompanied by Moro, the sultan's brother), got up to meet him, and he very kindly welcomed and exchanged pleasantries with them. As we have described earlier, he spoke softly, with temperate speech, with the elegance of the attitude of a Sultan, and a Moor by nation. His clothes were in the fashion of other inhabitants of his country, but much more luxurious, as demanded by his existence and status; from the waist to the ground he wore very rich gold-embroidered cloth. His legs were bare, but on his feet were a pair of red velvet shoes; his headdresses encrusted with gold-plated rings, one or one and a half inches wide, which made them beautiful and princely, like a crown; on his neck he wore a chain of pure gold with very large links and one fold double; on his left hand was a diamond, an emerald, ruby and turquoise stones, 4 very beautiful and perfect gemstones; on his right hand, in a ring, was a big, perfect turquoise stone, and in the other ring were many smaller diamonds, which were very artistically set together.

- Thus he sat on the throne of his kingdom, and on the right stood a servant with a very expensive fan (richly embroidered and decorated with sapphires). He fanned and gathered the air to cool the sultan, for his place was very hot, both because of the sun and the gathering of so many people. After some time, after the gentlemen had conveyed their message, and received an answer, they were allowed to leave, and were safely brought back by one of the chiefs of the Sultan's Council, which the Sultan himself commissioned to do".[42]

Sultan Babullah and the golden age of Ternate

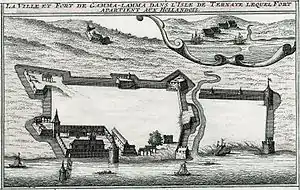

With the departure of the Portuguese, Sultan Babullah converted São João Baptista into his own fortress which also served as a palace. He renovated and strengthened the site and changed its name to Gammalamo. Under the aegis of Babullah the trading fleets from Melaka continued to arrive at Ternate from year to year, so that the flow of commerce with the European and wider world continued. No more granting of privileges were issued, thus Western merchants were treated similar to traders from other countries and they were kept under strict surveillance. Sultan Babullah even issued a regulation requiring every European arriving in Ternate to remove his hats and shoes, just to remind them not to forget themselves.[43]

Sultan Babullah maintained or created a network of alliances with other rulers and places in the Indonesian Archipelago. The Javanese Muslims from the port kingdoms of the Pesisir (north coast) became the steady allies of Ternate.[44] Frequent visits were undertaken to the areas claimed by Ternate, where their loyalty to the Sultan's policy was requested. In 1580 Babullah is said to have led a grand naval expedition (hongi) that visited a number of places in Sulawesi. The ruler also paid a visit to Makassar and met with the king of Gowa, Tunijallo. The two rulers concluded an alliance, whereby Babullah invited Tunijallo to convert to Islam. The king politely declined to become a Muslim, but as a sign of the new bond Sultan Babullah built a fortress at the Gowan coast called Somba Opu. His fleet then proceeded to conquer the island of Selayar south of Sulawesi.[45]

Under the leadership of Babullah, the Sultanate of Ternate reached its height of glory. A combination of Islamic socio-political influence, the after-effects of the Portuguese presence, and the rising clove sales, intensified royal control over territories and spices.[46] Early in his reign, the Sultan dispatched fleets to subjugate Buru, Ceram, and parts of Ambon; and in 1580 the chiefdoms in North Sulawesi were subordinated. Local tradition says that Ternate used a combination of interference in internal power struggles and marriage politics to gain influence. King Humonggilu of Limboto called in Ternatan assistance to defeat his adversary Pongoliwu of Gorontalo, then marrying Babullah's sister Jou Mumin.[47] The sister of the defeated king was in turn brought to Ternate and married to a grandee. Babullah himself supposedly married a princess from the Tomini Bay, Owutango, who had a pivotal role in spreading Islam in the region.[48] During the 1580 expedition Banggai, Tobungku (both in eastern Sulawesi), Tiworo (south-eastern Sulawesi) and Buton likewise fell under the Sultan's sway. Ternatan influence was also felt in the Solor Islands close to Timor, with access to the Timorese sandalwood,[49] and on the nutmeg-producing Banda Islands.[50] A list of dependencies drawn up by the Spaniards in c. 1590 furthermore mentions Mindanao, the Papuan Islands and the Sumbawan kingdoms Bima and Kore, though these places were probably only very loosely attached.[51] While the outlying areas were merely tributaries, other regions were placed under deputy rulers appointed by the sultan, called Sangaji (honoured prince). Babullah was nicknamed Ruler of 72 Islands, as related by the Dutch historian and geographer François Valentijn (1724).[52] At this stage the Ternate sultanate was by far the largest Islamic kingdom in eastern Indonesia.

Continued struggles with the Portuguese and Spaniards

His rule was far from unopposed, however. The Sultan of Tidore, Gapi Baguna, had supported Babullah after the murder of Hairun, but grew increasingly uneasy with Ternate's power ambitions. He therefore sailed over to Ambon in 1576 to draw up a strategical alliance with the Portuguese. On his way back he was trapped by a Ternate fleet and captured, though he was liberated through a daring raid by his kinsman Kaicili Salama.[53] Gapi Baguna now allowed the Portuguese to build a fort on Tidore (1578), hoping to attract the clove trade and secure military backing against Ternate. After the merger of Portugal with Spain in 1581, forces from the Spanish Philippines backed up the Iberian positions in Maluku. A Spanish force arrived to Tidore in 1582, and attempted to weaken Babullah through incursions on Ternate. However, the Spaniards were badly afflicted by an epidemic and had to return to Manila without achieving anything much.[54] The full consequences of the Spanish position in the Philippines were felt by Babullah's successor Saidi Berkat in 1606.[55]

Muslim diplomacy

The Sultan continued his father's policy of establishing ties with faraway Muslim polities. The years around 1570 witnessed a coordinated onslaught on the Portuguese possessions by the Muslim states of South India and Aceh with Ottoman backing, which was probably linked with Babullah's efforts.[56] All these attacks were defeated by the Portuguese - except in Maluku.[57] Babullah's envoy Kaicili Naik was dispatched to Lisbon where he met Philip II of Spain and Portugal and demanded that Hairun's murderer should be punished (though Pimentel had actually already been killed in an incident in Java[58]). The negotiations were inconclusive; however, the main purpose of the embassy was to make alliances on the way with Islamic rulers in Brunei, Aceh and Sunda (Banten?). When Kaicili Naik finally returned to Ternate after a successful mission, Babullah had already passed away.[59] Persons from the Ottoman Empire stayed at the court, and the Portuguese anxiously wrote about intimate contacts with Muslim figures from Aceh, the Malay World, and even Mecca. Javanese from Japara and other port kingdoms also assisted Ternate via Ambon. These far-flung contacts were signs of lively trade routes that had developed between different parts of Asia since the 15th century, which carried with them religious-cultural bonds. While the presence of Islam in Maluku had been patchy up to the mid-16th century, the age of Babullah and his successors saw a dissemination and deepening of religious observances, partly as a response to aggressive Catholic advances.[60]

Ternate post Babullah

Sultan Babullah passed away in July 1583.[61] The cause and place of his death are debatable. According to a late and unreliable story (by François Valentijn, 1724), he was lured on board a Portuguese ship and treacherously taken prisoner. The Sultan was brought towards Goa but passed away at sea. Other accounts allege that he was killed at home through poison or magic.[62] Whatever the circumstances, the strong and crafty Babullah was an inspiring leader who left a void that his successors could not entirely fill. In the history of Indonesia up to the 20th century, he was the only major leader who was able to win an absolute and uncontested victory over a Western power. His success in making Ternate into an extensive realm that reached its height of success in the late 16th century is only part of the picture. He also succeeded in instilling his people's confidence and rise up against a foreign power that strove to dominate their lives.[63] After the time of Sultan Babullah, no other leaders in Ternate and Maluku matched his caliber. In the face of new Spanish and Dutch advances in the early 17th century, the fabric of the Ternate polity proved too fragile to withstand colonial subordination.

Sultan Babullah was succeeded by his only historically ascertained son Sultan Saidi Berkat (r. 1583–1606), although his brother Mandar Syah was considered to have more legitimate claims. Saidi continued to wage war against the Portuguese and the Spanish with shifting success.[64]

Family

Sultan Babullah Datu Syah had the following known wives or co-wives:

- Bega, from the Sula Islands, mother of Saidi

- Owutango, a semi-legendary princess from the Tomini Bay, mother of Saharibulan

His known children were:

- Sultan Saidi Berkat (c. 1563–1628), ruler of Ternate 1583-1606

- Saharibulan, mentioned in North Sulawesi tradition

- Boki Ainalyakin, married Kodrat, Sultan of Jailolo

- Boki Randangagalo, married to a Sultan of Tidore, later with a Sultan of Bacan

See also

- Spice trade

- List of rulers of Maluku

- Sultanate of Ternate

- Sultanate of Jailolo

- Sultanate of Tidore

- Estado da India

- Governor of Maluku

Babullah of Ternate | ||

| Preceded by Hairun |

Sultan of Ternate 1570–1583 |

Succeeded by Saidi Berkat |

References

- Robert Cribb (2000) Historical atlas of Indonesia. Richmond: Curzon, p. 103.

- C.F. van Fraassen (1987) Ternate, de Molukken en de Indonesische Archipel. Leiden: Rijksmuseum te Leiden, Vol. I, p. 47.

- P.A. Tiele (1879) "De Europëers in den Maleischen Archipel", II:5, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 27, p. 39.

- Naïdah (1878) "Geschiedenis van Ternate", Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, 4:1, p. 441, 449.; C.F. van Fraassen (1987), Vol. II, p. 16.

- W.P. Coolhaas (1923) "Kroniek van het rijk Batjan", Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 63.

- Hubert Jacobs (1974) Documenta Malucensia, Vol. I. Rome: Jesuit Historical Institute, p. 239.

- Cf. Hubert Jacobs (1971) A treatise on the Moluccas (c. 1544). Rome: Jesuit Historical Institute, p. 123.

- Naïdah (1878), p. 449

- A.B. de Sá (1956) Documentação para a história das missões Padroado portugues do Oriente, Vol. IV. Lisboa: Agencia Geral do Ultramar, p. 185.

- Annabel Teh Gallop (2019) Malay seals from the Islamic world of Southeast Asia. Singapore: NUS Press, Nos 1836-1837.

- Hubert Jacobs (1974) Documenta Malucensia, Vol. I, Rome: Jesuit Historical Institute, p. 61; C.F. van Fraassen (1987), Vol. II, p. 16-7.

- Leonard Andaya (1993) The world of Maluku. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, p. 117.

- Leonard Andaya (1993), p. 122; P.A. Tiele IV:1, p. 399-400.

- P.A. Tiele IV:1, p. 405.

- Hubert Jacobs (1974), p. 12.

- P.A. Tiele IV:3, p. 418-20, IV:5, p. 440.

- P.A. Tiele IV:5, p. 438.

- Hubert Jacobs (1974), p. 624.

- P.A. Tiele IV:4, p. 441-3.

- Willard A. Hanna & Des Alwi (1990) Turbulent times past in Ternate and Tidore. Banda Naira: Yayasan Warisan dan Budaya Banda Naira, p. 86-7.

- Willard A. Hanna & Des Alwi (1990), p. 87.

- Bartholomew Leonardo de Argensola (1708) The Discovery and Conquest of the Molucco and Philippine Islands. London, p. 54.

- C.F. van Fraassen (1987), Vol. I, p. 40.

- Bartholomew Leonardo de Argensola (1708), p. 55

- Diogo do Couto (1777) Da Asia, Decada VIII. Lisboa : Na Regia officina typografica, p. 269-70.; Babullah marrying a sister of Sultan Tidore according to C.F. van Fraassen (1987), Vol. II, p. 16.

- François Valentijn (1724) Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien, Vol. I. Amsterdam: Onder de Linden, p. 144.

- P.A. Tiele (1877-1887) "De Europëers in den Maleischen Archipel", Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, 25-35, Part V:1, p. 161-2.

- Willard A. Hanna & Des Alwi (1990), p.88-91.

- A.B. de Sá (1956) Documentação para a história das missões Padroado portugues do Oriente, Vol. IV. Lisboa: Agencia Geral do Ultramar, p. 210.

- Ridjali (2004) Historie van Hitu. Houten: Landelijk Steunpunt Educatie Molukkers, p. 123.

- Gerrit Knaap (2004) Kruidnagelen en Christenen: De VOC en de bevolking van Ambon 1656-1696. Leiden: KITLV Press, p. 17-9.

- A.B. de Sá (1956), p. 331, 396-7.

- Hubert Jacobs (1974), p. 691; Georgius Everhardus Rumphius (1910) "De Ambonsche historie", Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, 64, p. 18-9. Buru later fell under Tidore's suzerainty for a while; see Hubert Jacobs (1980) Documenta Malucensia, Vol. II. Rome: Jesuit Historical Institute, p. 22;

- Willard A. Hanna & Des Alwi (1990), p. 92.

- Victor Lieberman (2009) Strange parallels: Southeast Asia in global contexts, c. 800-1830. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 853-4.

- P.A. Tiele IV:6, p. 455-6.

- Arend van Roever (2002) De jacht op sandelhout: De VOC en de tweedeling van Timor in de zeventiende eeuw. Zutphen: Walburg Pers.

- Willard A. Hanna & Des Alwi (1990), p. 98.

- Willard A. Hanna & Des Alwi (1990), p. 95-6.

- A.E.W. Mason (1943) The life of Francis Drake. London: Readers Union, p. 157.

- Willard A. Hanna & Des Alwi (1990), p. 102.

- Willard A. Hanna & Des Alwi (1990), p. 100-1. Slightly modernized text.

- Willard A. Hanna & Des Alwi (1990), p. 94.

- Hubert Jacobs (1980) Documenta Malucensia, Vol. II. Rome: Jesuit Historical Institute, p. 12.

- François Valentijn (1724) Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien, Vol. I. Amsterdam: Onder den Linden, p. 207-8.

- Victor Lieberman (2009), p. 853.

- M.H. Liputo (1949) Sedjarah Gorontalo Dua Lima Pohalaa, Vol. XI. Gorontalo: Pertjetakan Rakjat, p. 40.

- M.H. Liputo (1950) Sedjarah Gorontalo Dua Lima Pohalaa, Vol. XII. Gorontalo: Pertjetakan Rakjat, p. 23, 26-7.

- Arend de Roever (2002) De jacht op sandelhout; De VOC en de tweedeling van Timor in de zeventiende eeuw. Zutphen: Walburg Pers, p. 72.

- Peter Lape Contact and conflict in the Banda Islands, Eastern Indonesia, 11th-17th centuries. PhD thesis, Brown University, p. 64.

- P.A. Tiele (1877-1887), Part V:1, p. 161-2.

- François Valentijn (1724) Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien, Vol. I. Amsterdam: Onder de Linden, p. 208.; similarly denominated in Bartholomew Leonardo de Argensola (1708), p. 55.

- Hubert Jacobs (1974), p. 703-4; A.B. de Sá (1956), p. 354-6.

- P.A. Tiele (1877-1887), Part V:3, p. 179.

- Leonard Andaya (1993), p. 133, 140

- Anthony Reid (2006) "The pre-modern sultanate's view of its place in the world", in Anthony Reid (ed.), Veranda of violence; The background to the Aceh problem. Singapore: Singapore University Press, p. 57.

- C.R. Boxer (1969) The Portuguese seaborne empire. London: Hutchinson, p. 39-65.

- Hubert Jacobs (1980) Documenta Malucensia, Vol. II. Rome: Jesuit Historical Institute, p. 72.

- P.A, Tiele (1877-1887), Part V:4, p. 199.

- Leonard Andaya (1993), p. 132-7.

- P.A. Tiele (1877-1887), Part V:3, p. 180.

- Willard A. Hanna & Des Alwi (1990), p. 106.

- Leonard Andaya (1993), p. 136-7.

- Leonard Andaya (1993), p. 137-40.

Further reading

- M. Adnan Amal (2002) Maluku Utara: perjalanan sejarah 1250 - 1800, Volume I. Ternate: Khairun University.

- Willard A. Hanna & Des Alwi (1996) Masa lalu penuh gejolak. Jakarta: Pustaka Sinar Harapan.

- P.A. Tiele (1877-1887) "De Europëers in den Maleischen Archipel", Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, Nos. 25 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 35 , 36 .