Baseball in Cuba

Baseball was popularized in Cuba by Nemesio Guillot, who founded the first major baseball club in the country. It became the most played sport in the country in the 1870s, before the period of American intervention.

Despite its American origin, baseball is strongly associated with Cuban nationalism, as it effectively replaced colonial Spanish sports such as bullfighting. Since the Cuban Revolution, the league system in Cuba has been nominally amateur. Top players are placed on the national team, earning money for training and playing in international competitions.

History

The Early years (1864–1874)

Baseball was introduced to Cuba in the 1860s by Cuban students returning from colleges in the United States and American sailors who ported in the country. The sport spread quickly across the island nation after its introduction, with student Nemesio Guillot receiving popular credit date for the game's growth in the mid-19th century. Nemesio attended Spring Hill College in Mobile, Alabama, with his brother Ernesto. The two returned to Cuba, and in 1868 they founded the first baseball team in Cuba, the Habana Base Ball Club.

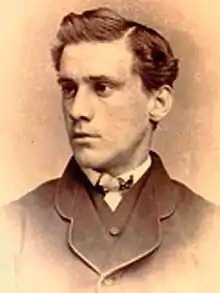

Soon after this, the first Cuban War of Independence spurred Spanish authorities in 1869 to ban the sport in Cuba. They were concerned that Cubans had begun to prefer baseball to bullfights, which Cubans were expected to dutifully attend as homage to their Spanish rulers in an informal cultural mandate. As such, baseball became symbolic of freedom and egalitarianism to the Cuban people. The ban may have also prompted Esteban Bellán, an early Cuban player, to remain in the United States and become the first Latin American player to appear in the major leagues. Bellán played baseball for the Fordham Rose Hill Baseball Club while attending Fordham University (1863–1868). After that he joined the professional Unions of Morrisania, a New York City team, followed by the Troy Haymakers. In 1871 the Haymakers joined the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players, which is regarded by many historians as a major league. Bellán played for them in 1871 and 1872, then moved to the New York Mutuals, another N.A. team, in 1873.[1]

The first official match in Cuba took place in Pueblo Nuevo, Matanzas, at the Palmar del Junco, December 27, 1874. It was between Club Matanzas and Club Habana, the latter winning 51 to 9. Bellán played for Habana and hit two home runs.[2]

Cuban baseball is organized (1878–1898)

In late 1878 the Cuban League was founded. At its inception the league consisted of three teams: Almendares, Havana, and Matanzas. Every team played the other two teams four times each. The first game was played on December 29, 1878, with Havana defeating Almendares 21 to 20. Havana, under team captain Bellán, went undefeated in the inaugural season and won the championship. The teams were composed amateurs and were all-white, however professionalism gradually took hold as teams bid on players to pry them from their rivals.

Cuban baseball becomes international (1898–1933)

The Spanish–American War brought increased opportunities to play against top teams from the United States. Also, the Cuban League admitted black players beginning in 1900. Soon many of the best players from the Northern American Negro leagues were playing on integrated teams in Cuba. Beginning in 1908, Cuban teams scored a number of successes in competition against major league baseball teams, behind outstanding players such as pitcher José Méndez and outfielder Cristóbal Torriente (who were both enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006). By the 1920s, the level of play in the Cuban League was superb, as Negro league stars like Oscar Charleston and John Henry Lloyd spent their winters playing in Cuba.

In 1899, the All Cubans, consisting of Cuban League professional players, were the first Latin American team to tour the United States. The team returned in 1902–05, exposing white Cuban players to U.S. major league and minor league scouts, and introducing black Cuban players to competition against the Negro leagues. Later Negro league teams included the Cuban Stars and the New York Cubans, which were stocked mostly with Cuban or other Latin American players.

Amateur baseball in Cuba (1933–1960)

Amateur baseball in Cuba was thriving in the 1940s and deepened the organization and maturity of the league. There were several amateur leagues in Cuba. Many of the leagues were composed of factory or businesses workers who represented their individual companies. Main sources of talent for Cuban baseball teams were from sugarmill baseball, semi-professional teams, and the amateur leagues. Original amateur teams represented exclusive social clubs in the Havana area, such as the Velado Tennis club.[3] The term “amateur baseball” is defined as “specifically the game played by social clubs who played in the Amateur league.”[3] Cubans refer to this league as los amateurs. The growth of amateur baseball can be attributed to the economic recovery in Cuba around 1934.[4] In 1934 there were only six teams but by 1940 that grew to eighteen.[5]

In 1954, amateur Dominican baseball became better organized, respected abroad, and very structured which led professional clubs to draw young talent from the ingenious leagues in cities throughout Cuba. Leagues which talented players were recruited from consisted of clever and unique ball players. The removal of some of the talented players in the league only slightly impacted the amateur leagues in Cuban cities. The young and talented team players who remained in the leagues gained physical strength by participating in the amateur games.

Amateur leagues were the heart and soul of Cuban baseball. The desire to throw, catch and hit a baseball was ingrained in young Cuban Amateur players. The leagues in Cuba participated in several championship tournaments. Cuban males were inclined to participate in the amateur leagues because they were an outlet from the everyday stresses they experienced in both work and family life. The passion of amateur play was not controlled by money or international recognition.

One major form of amateur baseball in Cuba was sugarmill baseball. Sugarmill baseball was popularized in the early 1950s.[6] This group of amateurs consisted mainly of players who were originally workers at the sugarmill. It was often loosely organized and regionally established. Each team represented a different sugarmill and they would compete against one another. Games were generally played on Sunday and holidays in order to leave weekdays reserved for field work.[7] Players in the league used sugarmill ball as an escape from the harsh working conditions of the mill. During the Golden Age of Cuban League sugarmill baseball was one of the most important producers of talent.

In Cuba’s amateur baseball leagues some of the greatest moments and players the game has ever produced on the island can be found, along with a high level of unconcealed iniquity. Until 1959 blacks were excluded from the amateur leagues.[8] Segregation is traced back to the start of the 20th century when disagreement among players regarding the professionalization of the game led to a split. The amateur game was the origin of the segregation and remained a sport played among exclusive social clubs and factory workers.[9] Membership in these clubs were restricted to whites, therefore blacks were excluded from amateur baseball and had to play for the semiprofessional teams. Whether the whites only policy was a direct consequence of American influence on upper-class Cubans or was a retention from colonial times is difficult to determine.[8]

The growth of education in Cuba led to the decline of amateur baseball. As the players became more educated, they attempted to bypass the amateur level of ball and head straight for the Professional leagues. The amateur leagues did not provide players with a large financial income. As players became more aware of the opportunities of the Professional leagues they aspired to gain recognition as ball players and join the Professional leagues. Much like the Opportunities the Professional leagues offered players gave them the option of playing for US teams and making more money.

During his reign, Castro implemented a system in which ball players could be locally sourced by state-sponsored programs. These programs allowed for young athletes to enhance their abilities. Every two to three years, players would be promoted to different levels based on skill. Parents were encouraged to place particularly talented children in the program at an early age. Children who participated in these programs were sometimes offered amenities such as more comfortable living, opportunities to travel and compete, pocket money, access to better food, etc. Placing a young generation in such state-controlled camps allowed for the regime to foster a new generation of loyalists.[10]

In Amateur baseball fields the home plates are made of wood. The fields are not in very good shape. The grandstands present at amateur baseball fields are protected by chicken wire and rarely painted. The maximum occupancy for a grandstand is 300 fans. Generally the stands are full and often fans will stand on the sidelines to watch the games. The stands at amateur games are filled with cane cutters and factory workers looking to enjoy life after a hard day's work in the fields. On the field the Cuban game has a few quirks (aluminum bats are allowed, and the umpire puts strikes before balls when he gives the count), but it closely resembles American baseball in both style and level of accomplishment. Today amateur baseball remains an outlet from a hard day's work in the fields and is still played by cane workers.

In 1960s the government abolished all professional sports on the island.[11] Sports were viewed as opposing the principles of the Revolution. With this thought in mind the ideas of sport were altered to better coincide with the ideology of the Revolution. To reshape baseball was a difficult task the idea of tradition had to be demolished and rebuilt.[11] Rewriting Cuban baseball history by connecting the president to the glory years of the Amateur Leagues began to take shape and reflect revolutionary ideas. From then on baseball and sports in Cuba were meant to encourage cooperation among nations, represent national pride, and promote fitness and military preparedness.[12] Through sports Cubans were able to feel personally involved in the nation building, socialization, and political integration of the revolution.[12] Fidel Castro said, “We can say that our athletes are the children of our Revolution and, at the same time, the standard-bearers of that same Revolution.”[13] In 1960, after the abolishment of all professional sports fans shifted their focus to the amateur leagues.

In the 1960s once amateur baseball became the main focus there was a strong desire to play and participate in sports. Cuban baseball shed its commercial skin and sought out to advance the social and political aims of the revolution via sport. The organization of the game and role baseball led in society was transformed. Changes were revolutionary and discrimination in amateur baseball was abolished. The reorganization of baseball after 1961, the durability and expansion of the structure of baseball, construction of new stadiums, and the production of players are all significant results the Revolution had on Cuban sports.[14] The island has remained the powerhouse of world amateur baseball since then.

Baseball in post-revolutionary Cuba (1961–present)

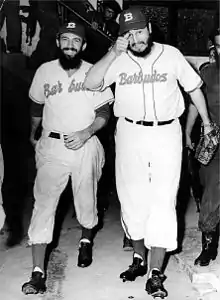

In 1959, the Cuban Revolution ushered in fundamental changes in how Cuban baseball was organized. The revolutionary government made baseball a symbol of excellence and used it to encourage nationalism.[15] Shortly after the revolution, victorious guerrilla leaders demonstrated their Cuban spirit by engaging in exhibition baseball games that included symbolic gestures reinforcing the notion that baseball would be an integral component of post-revolution Cuba.[16] In 1961, the Cuban government replaced the former professional baseball system with new amateur baseball leagues, most prominent among them the Cuban National Series. The reorganization aimed to organize the sport based on a socialist model of sports driven by national ideals rather than money.[17] Revolutionary officials believed that under capitalism sport is corrupted by the profit motive. The perversion of sport was believed to result in the exploitation of the masses.[18]

The shift from a professional to amateur system was preceded by the introduction of the Institute for Sports, Physical Education and Recreation (INDER).[19] The Cuban government made success in sports competitions a primary goal in the hopes that international sports triumphs could draw positive attention to the Cuban Revolution. In addition to displaying Cuba’s leadership to Third World countries, this would give Cubans themselves a sense of pride and feelings of nationalism for the Revolution. It was seen as a way of enhancing the revolutionary government’s legitimacy.[20] Much of Castro's vision towards establishing baseball as a prime means of nationalism was the state and government involvement in the sport. Local militia had a large role in monitoring the games. Many athletes were restricted to playing in their respective providences. In many instances, it was up to the political authorities to decide important management decisions as well as salaries for each player.[21] Sports participation in Cuba was also universalized and thus made an essential component of revolutionary activity. The term coined to describe such a process was Masividad, and sports served the purpose to not only educate and train the Cuban people, but also to allow them yet another opportunity to fit in an egalitarian society that conformed to the very principles of the revolution. The Cuban people also became healthier due to their participation in sporting related activities, especially those that promoted physical education. Most Cuban sports facilities and the equipment they possess are adequate and meet the needs of the people as thoroughly as possible. INDER has branches at the municipal, provincial and community level and is ultimately responsible for the delivery of all sport and physical education functions; and the coordination of all sport related systems, structures and services delivered by political, health, cultural, community development, education and sports agencies and institutions that traditionally function independently of each other.[22]

Although sport in general underwent a huge transformation after the revolution, it is still imperative to note that baseball continued to play a pivot role. After all it was Cuba’s bloodline and was easy to pick up and play since it required less conditioning and more focus on the crafting skills of hitting, pitching, and strategy.[23] Sports other than baseball retain some popularity in Cuba, including boxing and soccer, and the government continues to consider an athlete in fulfillment his or her duty as a Cuban citizen regardless of the sport pursued.[24] As mentioned earlier, sport in post-revolutionary Cuba was utilized to not only improve health, but in doing so citizens have become more prepared in-terms of self-defense in light of hostile policies at least in the early days of the revolution by the United States. Baseball, like all other sports in Cuba was also utilized for political ends. For instance, Cuba has allowed for the Cuban National Baseball team to play in countries abroad such as Nicaragua to benefit flood victims and in Japan as a symbolic gesture to express goodwill for a strong trading partner.[25] Such assistance by Cuba underlies its commitment to socialist internationalism, which still to this day sees a bevy of Cuban sports specialists training and instructing abroad citizens of other nations.[26]

Everything has seemingly been positive, however not everything went as planned. Since the professional system was abolished in-favor of amateur leagues, players were not paid as extravagantly as they once were. One report found that most baseball stars made less than $2,000 annually and that all players would receive sports leave pay at the same rate they would get from their off-season jobs as professionals, sports coaches, craftsmen, etc.[25] The situation would get worse in the early 1990s after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, which was Cuba’s main trading partner. This led many players to defect to the United States due to deteriorating economic conditions. Amidst such action, even Fidel Castro admitted himself that it's hard to prevent the baseball stars from defecting. He would later proclaim, “if you have to compete against six million dollars versus three thousand Cuban pesos you cannot win.”[27] Other problems included bribery scandals in which coaches and player alike would fix games, which subsequently led to them being banned from baseball in Cuba.[28] Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, there were also instances in Cuba where baseball games would be canceled due to power outages and most people chose to watch games from their home since it seemed more feasible to do so. The situation was so bad that pitchers in-game, would often have to exchange cleats with the pitcher who would have to pitch in the next half-inning.[27] Resources even as minute as baseball cleats were scarce during this very time. The Cuban government to this very day is also somewhat hostile in relation to the players that did defect in the 1990s.

Resumed exhibitions (1999–present)

In 1999, the Cuban national baseball team played a two-game exhibition series against the Baltimore Orioles of Major League Baseball. This marked the first time the Cuban national team played against an MLB team, and the first time an MLB team played in Cuba since 1959.[29] The Orioles won the first game, which was held in Havana, while the Cuban national team won the second game, which was held in Baltimore.

In December 2014, the United States and Cuba began to reestablish diplomatic relations. MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred entered into discussions to hold an exhibition game between an MLB team and the Cuban national team in 2016.[30]The Tampa Bay Rays played the Cuban national baseball team on March 22, 2016 in Havana's Estadio Latinoamericano. The Tampa Bay Rays defeated the Cuban national baseball team by a score of 4 to 1. The game was attended by U.S. President Barack Obama, Cuban President Raul Castro and Rachel Robinson, the widow of Jackie Robinson.[31]

In January 2019, Matthew McLaughlin became the first American to play in Cuba's National baseball system in over 60 years.[32]

Bibliography

- Bjarkman, Peter C. Baseball with a Latin Beat: A History of the Latin American Game. Jefferson, NC ;London: McFarland, 1994.

- González Echevarría, Roberto. The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball. New York [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press, 1999.

- Jamail, Milton Henry. Full Count: Inside Cuban Baseball. Writing baseball. Carbondale, Ill. ;Edwardsville, Ill: Southern Illinois Univ. Press, 2000.

- Klein, Alan M. Sugarball: The American Game, the Dominican Dream. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 1991.

- Pettavino, Paula. "Revolutionary Sport." The Cuba Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Ed. Chomsky, Carr, and Smorkaloff. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004. 192–200. Print.

- Wendel, Tim, Bob Costas, and Victor Baldizon. The New Face of Baseball: The One-Hundred Year Rise and Triumph of Latinos in America's Favorite Sport. New York: Rayo, 2004.

- Yiannakis, Andrew, and Merrill J. Melnick. Contemporary Issues in Sociology of Sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2001.

- Baird, K.E. (2005). "Cuban baseball: Ideology, politics, and market forces." Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 29(2), 164–183.

- Bjarkman, Peter. Diamonds Around the Globe. Greenwood Press. 2005. Print.

- Brown, Bruce. "Cuban Baseball." The Atlantic Monthly, 253(6), 109–114.

- Carter, Thomas F. "New Rules to the Old Game: Cuban Sport and State Legitimacy in the Post-Soviet Era." Identities 15.2 (2008): 194–215.

- Human Resource Development. "Second Meeting of the Human Resource Development (HRD) in Sport Committee." Report, 19–23 March 2003, 1–12.

- Jamail, Milton. Full Count Inside Cuban Baseball. Southern Illinois University, 2000. Print.

- Paula Pettavino & Geralyn Pye. "Revolutionary Sport." The Cuba Reader. Ed. Avita Chomsky, Barry Carr, & Pamela Maria Smorkaloff. Duke University Press. London, 2003. Print.

- Paula Pettavino & Philip Brener. "The Role of Sports in Cuba’s Domestic and International Policy." Cuba Briefing Paper, 21(4), 1–11.

- Pettavino, Paula. "Cuban Sports saved by Capitalism?" Report on Sport and Society, 37(5), 27–32.

- Pye, Geralyn. (1986). "The Ideology of Cuban Sport." Journal of Sport History, 13(2), 119–127.

- Steve Fainaru & Ray Sanchez. "Emigration in the Special Period." The Cuba Reader. Ed. Avita Chomsky, Barry Carr, & Pamela Maria Smorkaloff. Duke University Press. London. 2003. Print.

- Wysocki, David. "Fidel Castro’s Game: Baseball and Cuban Nationalism." The Chico Historian 19(2009): 143–157.

References

- "Cuban Baseball". Fordham University Libraries. Archived from the original on 2007-06-09. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- González Echevarría, p. 86.

- Gonzalez, R. “The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball,”189.

- Gonzalez, R. “The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball,”225.

- Gonzalez, R. “The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball,”225

- Gonzalez, R. “The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball,”191

- Klein, M. “Sugarball: The American Game, the Dominican Dream,”23

- Gonzalez, R. “The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball,”190.

- Gonzalez, R. “The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball,”191.

- Krall, Katie (Fall 2019). "Community, Defection, and equipo Cuba: Baseball under Fidel Castro, 1959-93". The Baseball Research Journal. 48 (2). Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- Jamail, H. "Full Count: Inside Cuban Baseball,"29.

- Pettavino, P. “The Cuba Reader: History, Culture, Politics,”475.

- Gonzalez, R. “The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball,”368.

- Gonzalez, R. “The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball,”367.

- Dierker, Larry. “Foreword,” Full Count Inside Cuban Baseball. Southern Illinois University, 2000. Print. xii, xiii.

- Carter, Thomas F. “New Rules to the Old Game: Cuban Sport and State Legitimacy in the Post Soviet Era.” Identitites 15.2 (2008): 200.

- Baird, K.E. (2005). “Cuban baseball: Ideology, politics, and market forces.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 29(2), 169.

- Pye, Geralyn. (1986). “The Ideology of Cuban Sport.” Journal of Sport History, 13(2). 125.

- Pettavino, Paula. “Cuban Sports Saved by Capitalism?” Report on Sport and Society, 37(5), 28.

- Paula Pettavino & Philip Brenner. “The Role of Sports in Cuba’s Domestic and International Policy.” Cuba Briefing Paper, 21(4), 2.

- Moreira Seijos, Onesimo Julian (4 November 2014). "Changes in Cuba's Migration Policy and Its Impact on Baseball". Journal of Arts & Humanities. 1 (8): 4. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- Human Resource Development. “Second Meeting of the Human Resource Development (HRD) in Sport Committee.” Report, 19–23 March 2003, 5.

- Wysocki, David. “Fidel Castro’s Game: Baseball and Cuban Nationalism.” The Chico Historian 19(2009), 147.

- Paula Pettavino & Geralyn Pye. “Revolutionary Sport.” The Cuba Reader. Ed. Avita Chomsky, Barry Carr, & Pamela Maria Smorkaloff. Duke University Press. London, 2003. Print, 475.

- Brown, Bruce. “Cuban Baseball.” The Atlantic Monthly, 253(6), 109.

- Paula Pettavino & Geralyn Pye. “Revolutionary Sport.” The Cuba Reader. Ed. Avita Chomsky, Barry Carr, & Pamela Maria Smorkaloff. Duke University Press. London, 2003. Print, 479.

- Steve Fainaru & Ray Sanchez. “Emigration in the Special Period.” The Cuba Reader. Ed. Avita Chomsky, Barry Carr, & Pamela Maria Smorkaloff. Duke University Press. London, 2003. Print, 639.

- Brown, Bruce. “Cuban Baseball.” The Atlantic Monthly, 253(6), 113.

- "Baltimore Orioles beat Cuba all-stars". CBC News. March 3, 1999. Retrieved March 15, 2013.

- Brian Costa (19 March 2015). "MLB Likely to Play Exhibition Game in Cuba". WSJ.

- Bort, Ryan. "PRESIDENT OBAMA ATTENDS BASEBALL GAME IN CUBA ALONGSIDE JACKIE ROBINSON'S WIFE". Newsweek.com. Newsweek. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- "Cuban baseball welcomes first U.S. player in six decades". Reuters. 22 January 2019. Retrieved 18 October 2019.