Battle of Golymin

The Battle of Golymin took place on 26 December 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars at Gołymin, Poland, between around 17,000 Russian soldiers with 28 guns under Prince Golitsyn and 38,000 French soldiers under Marshal Murat. The Russian forces disengaged successfully from the superior French forces. The battle took place on the same day as the Battle of Pułtusk.

| Battle of Golymin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Fourth Coalition | |||||||

Russian General Dmitriy Vladimirovich Golitsyn | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 38,000 soldiers[1] |

16,000–18,000 soldiers, 28 guns[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 700 | 750 | ||||||

Background

Strategic situation

After conquering Prussia in the autumn of 1806, Napoleon entered Poland to confront the Russian army, which had been preparing to support the Prussians until their sudden defeat. Crossing the river Vistula, the French advance corps took Warsaw on 28 November 1806.

The Russian army was under the overall command of Field Marshal Mikhail Kamensky, but he was old and becoming infirm. The Russian First Army of some 55,000 to 68,000 men,[3] commanded by Count Bennigsen, had fallen back from the Vistula to the line of the River Wkra,[4] in order to unite with the Second Army, about 37,000 strong,[5] under Buxhowden, which was approaching from Russia and was still some 15 days march from the First Army. However, realising his mistake in allowing the French to cross the Vistula, Kamensky advanced at the beginning of December to try to regain the line of the river.[6] French forces crossed the Narew River at Modlin on 10 December, and the Prussian Corps commanded by Lestocq failed to retake Thorn. This led Bennigsen on 11 December to issue orders to fall back and hold the line of the River Wkra.[7]

When this was reported to Napoleon, he assumed the Russians were in full retreat. He ordered the forces under Murat (the 3rd corps of Davout, 7th of Augereau and 5th under Lannes and the 1st Cavalry Reserve Corps) to pursue towards Pułtusk while Ney, Bernadotte and Bessières (6th, 1st and 2nd Cavalry Reserve Corps respectively) turned the Russian right and Soult's (4th Corps) linked the two wings of the army.[8]

Kamensky had reversed the Russian retreat, and ordered an advance to support the troops on the River Ukra.[9] Because of this, the French experienced difficulty crossing the river and it was not until Davout forced a crossing near the junction of the Wkra and the Narew on 22 December[10] that the French were able to advance.

On 23 December, after an engagement at Soldau with Bernadotte's 1st Corps, the Prussian corps under Lestocq was driven north towards Königsberg. Realising the danger, Kamensky ordered a retreat on Ostrolenka. Bennigsen decided to disobey and stand and fight on 26 December at Pułtusk. To the north-west, most of the 4th Division commanded by General Golitsyn and the 5th Division under General Dokhturov were falling back towards Ostrolenka via the town of Golymin. The 3rd Division under General Sacken, who had been the link with the Prussians, was also trying to retire via Golymin, but had been driven further north by the French to Ciechanów. Some of the 4th Division's units were at Pułtusk.[11]

Weather

The weather caused severe difficulties for both sides. Mild autumn weather had lasted longer than usual.[12] Normally, frosts made the inadequate roads passable after the muddy conditions of autumn but on 17 December there was a thaw,[13] followed by a two-day thaw beginning on 26 December.[14] The result was that both sides found it very difficult to manoeuvre. In particular the French (as they were advancing) had great difficulty bringing up their artillery, and so had none available at Golymin.

There were also difficulties with supply. Captain Marbot, who was serving with Augereau, wrote:

It rained and snowed incessantly. Provisions became very scarce; no more wine, hardly any beer, and what there was exceedingly bad, no bread, and quarters for which we had to fight the pigs and the cows.[15]

Terrain

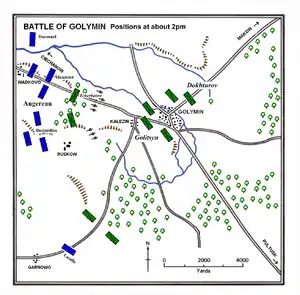

The village of Golymin lay in a flat area, with slight rises to the north and north-east. Woods and marshes almost surrounded the village. From the village, the road to Pułtusk ran south-east, that to Ciechanów north-west, and that to Makow (the destination for the Russian retirement) to the north-east. A track linked Golymin to the small village of Garnow to the south. The village of Ruskowo lay to the south-west, and that of Kaleczin a short distance to the west. Wadkowo lay further out along the Ciechanów road.

Battle

On the morning of 26 December, elements of Golitsyn's 4th Division reached Golymin. They were too exhausted to continue to Makow and Golitsyn also needed to wait for units of Sacken's 3rd Division. In the village he found Dokhturov, who had sent most of his 5th Division towards Makow, but remained at Golymin with a dragoon and an infantry regiment. Golitsyn hoped to rest his men before continuing their retreat.[16]

Murat's Reserve Cavalry Corps and Augereau's 7th Corps set out towards the town at first light (around 7 am). Lasalle's Cavalry Division were the first to arrive from the south-west at about 10am.[17] Golitsyn reinforced his rearguard of two squadrons of cavalry with three squadrons of cuirassiers, and Lasalle's men were driven back to the woods. But at around 2 p.m. Augereau's Corps appeared from the east. Golitsyn gave up his attempt to retreat, as his men were too exhausted to retire without fighting. He sent one regiment of infantry under the command of Prince Shcherbatov into the woods around Kaleczin and posted the rest of his troops in front of Golymin. He put his cavalry and Dokhturov's troops as his reserves, and positioned the rest of his division in front of Golymin.

Augereau's two divisions advanced, that of Haudelet on the left from Ruskow and Desjardins on the right from Wadkow. Desjardin's division at first drove back Shcherbatov, but being reinforced by an infantry battalion and with the support of their guns the Russians drove the French back. Heudelet's division made very little progress. For the rest of the day the forces skirmished as Heudelet's men slowly pushed round the Russian right.

About the same time as Augereau's attack started Murat arrived around Garnow with the cavalry divisions of Klein and Milhaud, and Davout's light cavalry. They drove the Russian cavalry into the woods to the south of Golymin, but were then unable to pursue further because the terrain was unsuitable for cavalry.

Golitsyn's force was now reinforced by two cavalry regiments from the 7th and 8th divisions, who had pushed past Augereau's cavalry on the Ciechanów road. However, Davout's 1st Division under Morand was beginning to arrive from the south-east. Golitsyn sent three infantry battalions into the woods and marshes to the south of Golymin, and two cavalry regiments to cover the Pułtusk road.

At about 3:30pm[18] Morand's first brigade attacked. After a struggle they drove the Russians out. Davout saw that the Russians were trying to retire towards Makow, and sent Morand's second brigade to advance via the Pułtusk road. A unit of dragoons led by General Rapp charged the Russian cavalry on the road, but found that the marshes on either side contained Russian infantry up to their waists in water and safe from the cavalry. The dragoons were driven back and Rapp was wounded. After taking the woods Morand's division did not advance further, concerned that there would be further useless losses.[19]

Night had now fallen and the Russians started to withdraw. Dokhturov's men led the way to Makow, then at about 9 p.m. Golitsyn sent off his guns, cavalry and then his infantry.

Augereau occupied Golymin early on 27 December.

Losses on both sides seem to have been around 800.[1]

Analysis

Golitsyn had the advantages of the terrain and support from his guns, when the French had no artillery. The French attacks were also uncoordinated, late in the day and, as dusk fell, illuminated as targets by the burning villages. On the other hand, Golitsyn's men were exhausted and outnumbered two to one. Their fierce resistance led Murat to say to Napoleon:

We thought the enemy had 50,000 men[20]

While the French held the field, Golitsyn achieved his objective of withdrawing and Murat failed to stop him.

Aftermath

General Golitsyn's successful delaying action, combined with the failure of Soult's corps to pass round the Russian right flank destroyed Napoleon's chance of getting behind the Russian line of retreat and trapping them against the River Narew.

The dogged resistance and obedience to orders of the Russian infantry greatly impressed the French. Captain Marbot noted:

The Russian columns were at this moment passing through the town [Golymin], and knowing that Marshal Lannes was marching to cut off their retreat by capturing Pułtusk, three leagues farther on, they were trying to reach that point before him at any price. Therefore, although our soldiers fired upon them at twenty-five paces, they continued their march without replying, because in order to do so they would have had to halt, and every moment was precious. So every division, every regiment, filed past, without saying a word or slackening its pace for a moment. The streets were filled with dying and wounded, but not a groan was to be heard, for they were forbidden.[21]

The Russian 5th and 7th Divisions retired towards the main body of the army at Różan. Bennigsen's forces fell back to Nowogród on the River Narew, uniting on 1 January 1807 with the forces under Buxhowden.

On 28 December Napoleon stopped his advance and, having lost contact with the Russian army, decided to go into winter quarters. His troops were exhausted and discontented, and the supply situation was in great disorder.[22]

The break in hostilities did not last long. On 8 February 1807 the two armies faced each other at the dreadful Battle of Eylau.

Forces involved

This list is derived from the units referred to in Petre's "Napoleon's Campaign in Poland 1806–1807",[23] and by checking the details for the same formations for the order of battles for Jena[24] and Elyau.[25] Milhaud's cavalry unit does not appear in either reference.

The French list is more detailed as there are more sources to work from. Petre was using the French Army archives for his research, and most unit details appear to be taken from there. The sources referred to give unit compositions down to individual battalions and squadrons.

Petre's source for the Russian units present was the memoirs of Sir Robert Wilson, British liaison officer with the Russian army. This was published in 1810 ("Remarks on the Russian Army"). It does not appear to contain any further information to help identify individual units. Stolarski's article[25] appears to make too many assumptions about the Russian order of battle at Eylau to be reliable.

- French

- Reserve Cavalry Corps – Marshal Murat

- Light Cavalry Division under Lasalle – Two Brigades totalling 12 squadrons of Hussars and Chasseurs.

- Light Cavalry Brigade under Milhaud – Four squadrons(?) (800 men)[26]

- Dragoon Cavalry Division under Klein – Three Brigades totalling 19 squadrons of Dragoons.

- 3rd Corps – Marshal Davout

- 1st Infantry Division under Morand – Three Brigades totalling 12 battalions of infantry.

- 2nd Infantry Division under Friant – Three Brigades totalling 8 battalions of infantry (not engaged)

- Light Cavalry Division under Marulaz – Nine squadrons of Chasseurs

- 7th Corps – Marshal Augereau

- 1st Infantry Division under Desjardin – Two Brigades totalling 11 battalions of infantry

- 2nd Infantry Division under Heudelet – Three Brigades totalling 11 battalions of infantry

- Light Cavalry Division under Durosnel – Seven squadrons of Chasseurs

Note: No guns are mentioned as the French were not able to bring them up due to the muddy conditions.[27]

- Russian

- 4th Division – Prince Golitsyn

- 15 battalions of infantry,

- 20 squadrons of cavalry (Cuirassiers and Hussars),

- 28 guns

- 7th Division – General Dokhturov (part)

- 3 battalions of infantry,

- 2 regiments of cavalry

- 3rd Division – General Sacken (part)

- Some infantry

- 2 regiments of cavalry

Footnotes

- Petre "Poland", 2001 ed, p114

- Petre "Poland", 2001 ed, p113

- Petre "Poland", 2001 ed, p38

- Petre "Poland", 2001 ed, p70

- Petre "Poland", 2001 ed, p39

- Petre "Poland", 2001 ed, p40

- Petre "Poland", 2001 ed, p73

- Petre "Poland", 2001 ed, p76

- Petre "Poland", 2001 ed, p77

- Petre "Poland", 2001 ed, p79-82

- Petre "Poland", 2001 ed, p89

- Petre "Poland", 2001 ed, p354

- Correspondance de Napoleon Ier, XI 497

- Petre "Campaign in Poland", 2001 ed, p40

- Marbot "Memoirs", 1:xxvii

- For details see Petrie "Poland" 2001 ed, p.107-114; Chandler "Campaigns" p.524; Chandler "Dictionary" p.173

- Chandler, ed. "Dictionary" p.173

- Petrie "Poland" 2001 ed, p.111

- Petrie "Poland" 2001 ed, p.107-114

- Petre "Poland", 2001 ed, p115, quoting from Hoepfner, Gen. E von, "Der Kreig von 1806 und 1807" Berlin, 1855. iii, 126

- Marbot "Memoirs", 1.xxviii

- Petre "Poland", 2001 ed, p117

- Petre "Poland", 2001 ed, p113 -114

- Chandler, David G. "Jena 1806". Osprey 1993. ISBN 1-85532-285-4

- Stolarski. P; "Elyau", Miniature Wargames Magazine, March 1997

- Petre "Poland" p.64

- Petre "Poland", 2001 ed, p109, 111

References

- Chandler, David G. The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995. ISBN 0-02-523660-1

- Chandler, David G. Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars. Ware: Wordsworth Editions Ltd, 1999. ISBN 1-84022-203-4

- Marbot, Baron M. "The Memoirs of Baron de Marbot". Translated by A J Butler. Kessinger Publishing Co, Massachusetts, 2005. ISBN 1-4179-0855-6 (References are to book and chapter). Also available on line (see external links below).

- Petre, F. Loraine. Napoleon's Campaign in Poland 1806–1807. First published 1901; reissued Greenhill Books, 2001. ISBN 1-85367-441-9. Petre used many first hand French sources, German histories and documents from the French Army archives. However he spoke no Russian so was not able to use any Russian sources.