Battle of Rocquencourt

The Battle of Rocquencourt was a cavalry skirmish fought on 1 July 1815 in and around the villages of Rocquencourt and Le Chesnay. French dragoons supported by infantry and commanded by General Exelmans destroyed a Prussian brigade of hussars under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Eston von Sohr (who was severely wounded and taken prisoner during the skirmish).

| Battle of Rocquencourt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Napoleonic Wars (Seventh Coalition 1815) | |||||||

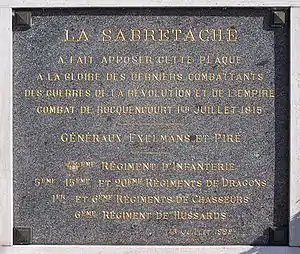

Commemorative plaque. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

3,000 blocking cavalry 1 cavalry division three infantry battalions(from the 33rd Regiment)[1] | 600–700 officers and light cavalry troopers[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | 10 officers and 400–500 troopers[2] | ||||||

Prussian cavalry detachment under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Sohr ventured too far in advance of the main body of the Prussian army with the intention of reaching the Orléans road from Paris; where his detachment was to interrupt traffic on the road, and increase the confusion already produced in that quarter by the fugitives from the capital. However, when the Prussian detachment was in the vicinity of Rocquencourt it was ambushed by a superior French force. Under attack the Prussians retreated from Versailles and headed east, but were blocked by the French at Vélizy. They failed to re-enter Versailles and headed for Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Their first squadron came under fire at the entrance of Rocquencourt and attempted to escape through the fields. They were forced into a small, narrow street in Le Chesnay and killed or captured. Just before nightfall the same day, the advanced guard of the Prussian III Corps, having heard of the destruction of Sohr's detachment, succeeded in recapturing Rocquencourt and bivouacked there.

Prelude

After its defeat at the Battle of Waterloo on 18 June 1815 the remnants of the French Army of the North fell back on Paris, where it was reinforced by some fresh regular army regiments and the French National Guard. They were pursued and harried by the Anglo-Allied and Prussian armies which by 29 June were less than five miles from Paris.[3]

The Duke of Wellington, the commander of the Anglo-Allied army, and Prince Blücher the commander of the Prussian army, met on the evening of the 29 June and determined that one army would confront the French behind their strongly fortified lines line of Saint-Denis and Montmartre while the other army would move off to the right and cross to the left back of the river Seine down stream of the lines. Although this plan was not without risks the allied Coalition commanders decided that the potential benefits outweighed the risks.[4]

During the 29 June, as the Coalition forces approached Paris it had also been tolerably well ascertained that, although fortified works had been thrown up on the right bank of the Seine, the defence of the left bank had been comparatively neglected. A further inducement towards the adoption of this plan arose from a report which was now received from Major Colomb, stating that although he had found the bridge of Chatou, leading to Château de Malmaison, destroyed: he had hastened to that of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, on hearing that it had not been damaged; and succeeded in gaining possession of it at the very moment the French were on the point of blowing it up. The bridge of Maisons, still lower down stream, was also taken and occupied.[5]

No time was lost by the Prussian Commander in taking advantage of the captured bridges across the Seine.[5] One of his orders that night was for Lieutenant Colonel Eston von Sohr. He was to move, with his cavalry brigade (the Brandenburg and Pomeranian Hussars), from the vicinity of Louvres, and to regulate his march so that he might cross the Seine at Saint-Germain on the following morning. Thence he was to proceed so as to appear, with his brigade, on 1 July, upon the Orléans road from Paris; where he was to interrupt traffic on the road, and increase the confusion already produced in that quarter by the fugitives from the capital. Altogether, he was to act independently and at his own discretion; and, as far as practicable, to impede the supplies of provisions from the western and southern Provinces.[5]

Starting at daybreak of 30 June, the Colonel Sohr's brigade passed through Montmorency and Argenteuil, towards Saint-Germain; where it fell in with Major Colomb's detachment, consisting of the 8th Hussars and two battalions of Infantry. It then moved on about a league further, to Marly, upon the Versailles road; which it reached at nightfall, and where it bivouacked.[6]

On the morning of 1 July, Lieutenant Colonel Sohr resumed his march, and took the direction of Versailles, which place, however, he did not reach until noon; much delay having occurred whilst passing through the intersected ground in that quarter, and in awaiting the reports from the detachments sent out in different directions to gain intelligence of the French.[6]

French preparations for an ambush

This bold and hazardous movement of Lieutenant Colonel Sohr's brigade, which was acting independently for the time, did not escape the observation of the French. General Exelmans, who commanded the French cavalry on the south side of Paris, on receiving information that two regiments of Prussian Hussars were advancing by Marly upon Versailles, resolved to attack them.[6]

For this purpose he proceeded himself with the 5th, 15th, and 20th dragoons, and the 6th Hussars, comprising a force of 3,000 men, along the road from Montrouge towards Plessis-Piquet, against the front of the Prussian brigade.[1]

At the same time, the Light Cavalry Division of General Piré, together with the 33rd Regiment of Infantry, consisting of three battalions, were detached against the flank and rear of the Prussian brigade. The 5th and 6th Lancers marched by the Sèvres road upon Viroflay; the 6th Chasseurs proceeded to occupy the cross roads connecting Sèvres with the northern portion of Versailles; the 1st Chasseurs moved by Sèvres towards Rocquencourt, about three miles from Versailles, on the road to Saint-Germain; in which direction the 33rd Infantry followed. Both the latter regiments were destined to cut off the retreat of the Prussian cavalry, should it be driven back by Exelmans.[7]

An exceedingly well planned ambush was now laid in and about Rocquencourt, and every precaution taken by the detaching of small parties on the look out.[7]

Battle

The French ambush is sprung

It was late in the afternoon when Lieutenant Colonel Sohr received intelligence that the French cavalry was approaching, and that his advanced guard was attacked. He immediately advanced with both his Hussar regiments, and drove the French back upon Vélizy, in the defile of which village a sharp engagement ensued. In this attack the ranks of the Prussian Hussars had become disordered; and, as the latter retired, they were fallen upon by the 5th and 6th French Lancers of Piré's light cavalry brigade, which had been posted as part of the ambush.[7]

The Prussians then fell back upon Versailles, pursued by the French; who vainly endeavoured to force an entrance into the town, at the gate of which a gallant resistance was made by the Prussians. The short time that was gained by this resistance sufficed for collecting the main body of the brigade on the open space at the outlet leading to Saint-Germain, towards which point it might have retreated through the Park; but having received information of the advance of Prussian III Corps commanded by Johann von Thielmann, and expecting every moment to receive support, Lieutenant Colonel Sohr retired by the more direct road through Rocquencourt.[8]

Prussian hussars try to cut their way out

About seven o'clock in the evening, at which time the Hussars had collected their scattered force together, and were on the point of commencing their further retreat upon Saint-Germain; Sohr received intelligence, upon which he could rely, that he had been turned by both cavalry and infantry; and that his line of retreat had been intercepted. His decision was instantly formed. He knew his men, their devotion, and their courage; and resolved upon cutting his way through the French with the sword.[9]

On quitting Versailles the Prussian Hussars were fired upon by the National Guard from the barrier. They had not proceeded far when word was brought in, that Prussian and British cavalry were approaching from the side of Saint-Germain; but it turned out to be a false report as what had been observed was the 1st Regiment of French Chasseurs. In the next moment the Prussians Hussars were formed for attack, and charged at a gallop.[9]

The Chasseurs came on in the same style; but they were completely overthrown, and their commanding officer lay stretched upon the ground by a pistol shot. As the Chasseurs were pursued by the Hussars, two companies of the 3rd Battalion of the 33rd French Infantry Regiment, posted behind some hedges, near Le Chesnay opened fire on the Prussians. The Hussars reacting to the musket fire, struck into a field road to the right, to turn this village, which was occupied by the French.[9]

This, however, led them to a bridge, with adjacent houses, occupied by two more companies of the above 3rd Battalion from which they also received a sharp fire. Meeting with this new obstacle, and aware of the proximity of the great mass of cavalry under Excblmans, in their rear; the diminished and disordered remnant of the two Prussian regiments, about 150 Hussars, rallying upon their commander, dashed across a meadow, with the intent of forcing a passage through the Village of Le Chesnay.[10]

Fight in the Courtyard at Le Chesnay

In Le Chesnay the Chasseurs again opposed them, but were once more overthrown; and the Prussians now followed a road which conducted them through the village, but which led into a large courtyard from which there was no other way out.[2]

Not only was their further progress thus checked, but their whole body was suddenly assailed by a fire from French infantry, already posted in this quarter; whilst the pursuing cavalry prevented every chance of escape. Their situation had become truly desperate; but their bravery, instead of succumbing, appeared incited to the highest pitch by the heroic example of Lieutenant Colonel Sohr, their commander, who rejected an offer of quarter. Rather than face annihilation, after Lieutenant Colonel Sohr, was severely wounded by a pistol shot, a few surviving Prussians surrendered.[2]

The losses incurred by this brigade during the short campaign had already reduced it, prior to this battle, to between 600 and 700 men, and on the present occasion it suffered a still further loss of ten officers, and from 400 to 500 men.[2]

Aftermath

The advanced guard of Thielemann's Prussian III Corps, consisting of the 9th Infantry Brigade, under General Borcke, was on the march from Saint-Germain (which it had left about seven o'clock in the evening) to take post at Marly; when it received intelligence of the two cavalry regiments, under Lieutenant Colonel Sohr, had been completely defeated. Borcke hastened forward, and it was not long before his advance became engaged with the French Tirailleurs advancing from Versailles. The French was immediately attacked, and were driven back upon Rocquencourt. As darkness was setting in, Borcke drew up his force with caution. He pushed forward the Fusilier Battalion of the 8th Regiment, supported by the 1st Battalion of the 30th Regiment; and held the remainder in Battalion Columns on the right and left of the road. The vigour of the attack made by the Fusiliers was such that the French retired in all haste upon the nearest suburb of Paris; whilst Borcke bivouacked at Rocquencourt.[11]

Analysis

Historian William Siborne states that victory favoured the strongest and the best prepared, but it was a French victory gained over a gallant band of warriors; who fought to the last, and did all that the most inflexible bravery could accomplish.[2]

In the opinion of Siborne, the detaching of these two regiments so much in advance of the Prussian general movement to the right; and the orders given to Lieutenant Colonel Sohr, to cross the Seine on the morning of 30 June, appear a questionable measure. It is true that this officer was desired to consider himself as acting independently, and without reference to the troops that were to follow in the same direction; but then it must be recollected that he had to proceed along a very considerable portion of the circumference of a circle, from the centre of which the French could detach superior force along radii far shorter than the distance between the Prussian brigade and the main Prussian army; so that, with a vigilant look out, the French possessed every facility of cutting off his retreat. In the circumstances, the preferable course would have been, to have employed Soke's brigade as an advanced guard only; having immediate support from the main columns in its rear.[12]

Notes

- Siborne 1848, pp. 741–742.

- Siborne 1848, p. 744.

- Siborne 1848, p. 710.

- Siborne 1848, p. 727.

- Siborne 1848, p. 728.

- Siborne 1848, p. 741.

- Siborne 1848, p. 742.

- Siborne 1848, pp. 742–743.

- Siborne 1848, p. 743.

- Siborne 1848, pp. 743–744.

- Siborne 1848, p. 746.

- Siborne 1848, p. 745.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Siborne, William (1848), The Waterloo Campaign, 1815 (4th ed.), Westminster: A. Constable

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Siborne, William (1848), The Waterloo Campaign, 1815 (4th ed.), Westminster: A. Constable