Battle of Magdhaba

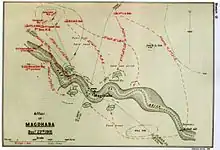

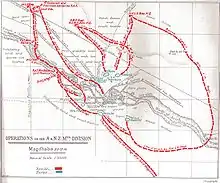

The Battle of Magdhaba (officially known by the British as the Affair of Magdhaba) took place on 23 December 1916 during the Defence of Egypt section of the Sinai and Palestine Campaign in the First World War.[1][Note 1] The attack by the Anzac Mounted Division took place against an entrenched Ottoman Army garrison to the south and east of Bir Lahfan in the Sinai desert, some 18–25 miles (29–40 km) inland from the Mediterranean coast. This Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) victory against the Ottoman Empire garrison also secured the town of El Arish after the Ottoman garrison withdrew.

| Battle of Magdhaba | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I | |||||||

Camel corps at Magdhaba by Harold Septimus Power, 1925 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

1st Light Horse Brigade 3rd Light Horse Brigade New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade Imperial Camel Brigade RAN Bridging Train |

80th Infantry Regiment (2nd and 3rd Battalions) Supporting troops | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 6,000 | 2,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

22 dead 124 wounded |

300+ killed of whom 97 confirmed dead 300 wounded of whom 40 confirmed cared for 1,242–1,282 prisoners | ||||||

Location within Sinai | |||||||

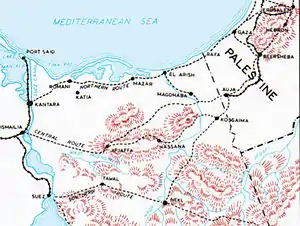

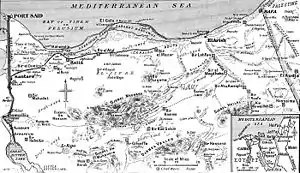

In August 1916, a combined Ottoman and German Empire army had been forced to retreat to Bir el Abd, after the British victory in the Battle of Romani. During the following three months the defeated force retired further eastwards to El Arish, while the captured territory stretching from the Suez Canal was consolidated and garrisoned by the EEF. Patrols and reconnaissances were carried out by British forces, to protect the continuing construction of the railway and water pipeline and to deny passage across the Sinai desert to the Ottoman forces by destroying water cisterns and wells.

By December 1916, construction of the infrastructure and supply lines had sufficiently progressed to enable the British advance to recommence, during the evening of 20 December. By the following morning a mounted force had reached El Arish to find it abandoned. An Ottoman Army garrison in a strong defensive position was located at Magdhaba, some 18–30 miles (29–48 km) inland to the south east, on the Wadi el Arish. After a second night march by the Anzac Mounted Division (Australian and New Zealand Mounted Division), the attack on Magdhaba was launched by Australian, British and New Zealand troops against well-entrenched Ottoman forces defending a series of six redoubts. During the day's fierce fighting, the mounted infantry tactics of riding as close to the front line as possible and then dismounting to make their attack with the bayonet supported by artillery and machine guns prevailed, assisted by aircraft reconnaissances. All of the well-camouflaged redoubts were eventually located and captured and the Ottoman defenders surrendered in the late afternoon.

Background

At the beginning of the First World War, the Egyptian police who had controlled the Sinai Desert were withdrawn, leaving the area largely unprotected. In February 1915, a German and Ottoman force unsuccessfully attacked the Suez Canal.[2] After the Gallipoli Campaign, a second joint German and Ottoman force again advanced across the desert to threaten the canal, during July 1916. This force was defeated in August at the Battle of Romani, after which the Anzac Mounted Division, also known as the A. & N. Z. Mounted Division, under the command of the Australian major general Harry Chauvel, pushed the Ottoman Army's Desert Force commanded by the German general Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein out of Bir el Abd and across the Sinai to El Arish.[3][4]

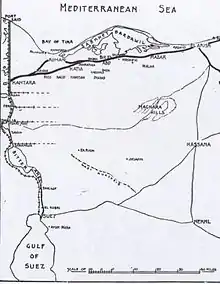

By mid-September 1916 the Anzac Mounted Division had pursued the retreating Ottoman and German forces from Bir el Salmana 20 miles (32 km) along the northern route across the Sinai Peninsula to the outpost at Bir el Mazar. The Maghara Hills, 50 miles (80 km) south west of Romani, in the interior of the Sinai Desert, were also attacked in mid-October by a British force based on the Suez Canal.[5] Although not captured at the time, all these positions were eventually abandoned by their Ottoman garrisons in the face of growing British Empire strength.[6]

Consolidation of British territorial gains

The British then established garrisons along their supply lines, which stretched across the Sinai from the Suez Canal. Patrols and reconnaissances were regularly carried out to protect the advance of the railway and water pipeline, built by the Egyptian Labour Corps.[7] These supply lines were marked by railway stations and sidings, airfields, signal installations and standing camps where troops could be accommodated in tents and huts. At this time the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) had a ration strength of 156,000 soldiers, plus 13,000 Egyptian labourers.[8]

Ottoman positions in the Sinai

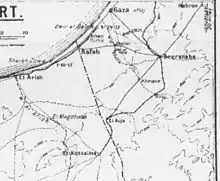

The Ottoman Army's Desert Force commanded by Kress von Kressenstein which operated in the Sinai region was sustained and supported by their principal desert base at Hafir El Auja, located on the Ottoman side of the Egyptian-Ottoman frontier. Hafir el Auja was linked to Beersheba, Gaza, and northern Palestine by road and railway.[3][9][10][Note 2][Note 3]

This major German and Ottoman base in the central Sinai desert, supplied and supported smaller garrisons in the area with reinforcements, ammunition and rations, medical support, and periods of rest away from the front line.[Note 4] If left intact, the Ottoman forces at Magdhaba and Hafir el Auja could seriously threaten the advance of the EEF along the north route towards Southern Palestine.[7][11][Note 5]

Water

The area of oases which extended from Dueidar, 15 miles (24 km) from Kantara along the Darb es Sultani, along the old caravan route, and on to Salmana 52 miles (84 km) from Kantara could sustain life. But from Salmana to Bir el Mazar, (75 miles (121 km) from Kantara) there was little water, and beyond the Mazar area there was no water, until El Arish was reached on the coast 95 miles (153 km) from Kantara.[12]

Before the British advance to El Arish could begin, the 20 miles (32 km) stretch without a water supply between El Mazar and El Arish had to be thoroughly explored. By mid-December 1916, the pipeline's eastward progress made it possible to store sufficient water at Maadan (Kilo. 128) and it was also possible to concentrate sufficiently large numbers of Egyptian Camel Transport Corps camels and camel-drivers to carry water forward from Maadan in support of an attacking force.[13][14][15]

Conditions

The campaign across the Sinai desert required great determination, as well as conscientious attention to detail by all involved, to ensure that ammunition, rations and every required pint of water and bale of horse fodder was available when needed. While the Ottoman Empire's main desert base at Hafir el Auja was more centrally located, the British Empire base was some 30 miles (48 km) to the west of El Arish; almost at the limits of their lines of communication. Mounted operations so far from base in such barren country were extremely hazardous and difficult.[16]

For these long-range desert operations, it was necessary for all supplies to be well-organised and suitably packaged for transportation on camels, moving with the column or following closely behind. It was vital that the soldiers were well trained for these conditions. If a man was left behind in the inhospitable Sinai, he might die in the burning desert sun during the day, or bitter cold at night. If a water bottle was accidentally tipped up or leaked, it could mean no water for its owner, for perhaps 24 hours in extreme temperatures.[16]

In these extreme and difficult conditions, mounted troops of the EEF worked to provide protective screens for the construction of the infrastructure, patrolling the newly occupied areas and carrying out ground reconnaissance to augment and verify aerial photographs, used to improve maps of the newly occupied areas.[17]

British War Office policy

The British War Office's stated policy in October 1916 was to maintain offensive operations on the Western Front, while remaining on the defensive everywhere else.[18] However, the battle of attrition on the Somme, coupled with a change of Britain's prime minister, with David Lloyd George succeeding H. H. Asquith on 7 December, destabilised the status quo sufficiently to bring about a policy reversal, making attacks on the Central Powers' weak points away from the Western Front desirable. The commander of the EEF, General Sir Archibald Murray, was encouraged to seek success on his eastern frontier, but without any reinforcements. He thought that an advance to El Arish was possible, and that such an advance would threaten forces in the southern Ottoman Empire and, if not prevent, at least slow the transfer of German and Ottoman units to other theatres of war from the Levant.[8][19]

Creation of Eastern Force and Desert Column

After the victory at Romani, Murray moved his headquarters back from Ismailia on the canal to Cairo. This move to Cairo was to enable him to be in a more central position to carry out his duties and responsibilities which extended from the Western Frontier Force, waging a continuing campaign against the Senussi in Egypt's Western Desert, to the Eastern Force in the Sinai. Another consequence of the victory was that Major General H. A. Lawrence, who had been in command of the Northern Sector of the Suez Canal defences and Romani during the battle, was transferred to the Western Front.[20][21][22]

As a consequence of pushing the German and Ottoman forces eastwards away from the canal, during October, Lieutenant General Charles Dobell was appointed to command the newly created Eastern Force.[23] With his headquarters at Kantara, Dobell became responsible for the security of the Suez Canal and the Sinai Peninsula.[7]

Trooper Ingham[24]

Dobell's Eastern Force consisted of two infantry divisions, the 42nd (East Lancashire) Division commanded by Major General W. Douglas and the 52nd (Lowland) Division commanded by Major General W. E. B. Smith, as well as the Anzac Mounted Division, a mounted infantry division commanded by Chauvel, the 5th Mounted Brigade commanded by Brigadier General E. A. Wiggin and the Imperial Camel Brigade commanded by Brigadier General Clement Leslie Smith.[25][26][Note 6] Murray considered this force to be under strength by at least a division for an advance to Beersheba, but felt he could gain El Arish and form an effective base on the coast, from which further operations eastwards could be supplied.[8][18]

In October Chauvel was granted six weeks' leave, and he travelled to Britain on 25 October, returning to duty on 12 December 1916.[27] While he was away Desert Column was formed and on 7 December 1916, five days before Chauvel's return, Murray appointed the newly promoted Lieutenant General Sir Phillip Chetwode commander of the column. As a major general, Chetwode had been in command of cavalry on the Western Front, where he was involved in pursuing retreating Germans after the First Battle of the Marne.[28]

On formation, Chetwode's Desert Column consisted of three infantry divisions, the 53rd (Welsh) Division, currently serving in the Suez Canal Defences and commanded by A. E. Dallas, and the 42nd (East Lancashire) and the 52nd (Lowland) divisions. Chetwode's mounted force consisted of the Anzac Mounted Division, the 5th Mounted Brigade and the Imperial Camel Brigade.[26][28]

Prelude

By early December 1916, construction of the railway had reached the wells at Bir el Mazar, the last water sources available to the EEF before El Arish. Bir el Mazar was about halfway between Kantara on the Suez Canal and the Egyptian-Ottoman territorial border. British intelligence had reported Ottoman Army plans to strengthen the garrison at Magdhaba, by extending the railway (or light rail) south east from Beersheba (and Hafir el Auja) towards Magdhaba.[6][12]

Advance to El Arish

Mounted patrols to the outskirts of El Arish discovered 1,600 well-entrenched Ottoman troops holding the town, supported by forces based 25 miles (40 km) to the south-east on the banks of the Wadi el Arish at Magdhaba and Abu Aweigila.[8]

On 20 December, a week after Chauvel returned from leave, the advance to El Arish began when the Anzac Mounted Division left Bir Gympie at 21:45. They moved out without the 2nd Light Horse Brigade, which was in the rear assisting with patrolling the lines of communication stretching 90 miles (140 km) back to Kantara on the Suez Canal. So it was the 1st and 3rd Light Horse Brigades, the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade, the 5th Mounted Brigade and the newly formed battalions of the Imperial Camel Brigade with the mountain guns of the Hong Kong and Singapore Camel Battery which made the 20-mile (32 km) trek to El Arish.[29][30]

On the day they set out, Australian airmen reported that the garrisons at El Arish and Maghara Hills, in the centre of the Sinai, appeared to have been withdrawn.[31][32]

As the Anzac Mounted Division approached Um Zughla at 02:00 on 21 December, a halt was called until 03:30 when the column continued on to El Arish. At 07:45, the advanced troops entered the town, unopposed, to contact the civil population and arrange water supplies for the mounted force. One prisoner was captured, while lines of observation were set up, which maintained a close watch over the country east and south of the town. By 16:00 the 1st and 3rd Light Horse, the New Zealand Mounted Rifles and the Imperial Camel Brigades were in bivouac at El Arish, the only casualties during the day being two members of the 1st Light Horse Brigade, who were blown up by a stranded mine on the beach.[33]

The day after El Arish was occupied, on 22 December, the leading infantry brigade of the 52nd (Lowland) Division reached the town and, together with the 5th Mounted Brigade, garrisoned the town and began fortifying the area.[34] At 10:00, Chetwode landed on the beach opposite the Anzac Mounted Division Headquarters to begin his appointment as commander of Desert Column.[35][36] Chetwode reported that he had arranged a special camel convoy with rations and horse feed to arrive at El Arish at 16:30 that day, with a view to the Anzac Mounted Division advancing on Magdhaba, 18 miles (29 km) away. (On the following day 23 December, the first supplies to be transported to El Arish by ship from Port Said were landed.) With essential rations organised, Chauvel led the mounted division out of El Arish at 00:45 on the night of 22/23 December towards Magdhaba, after reconnaissances had established that the retreating Ottoman force from El Arish had moved to the south east along the Wadi el Arish towards Magdhaba.[28][30][35]

Ottoman force

After their retreat from El Arish, the Ottoman garrison withdrew down the Wadi el Arish 25 miles (40 km) south east of El Arish, to Magdhaba and Abu Aweigila, about another 15 miles (24 km) further away from the coast, on the banks of the wadi.[32] At Magdhaba the garrison had increased from 500 to about 1,400 Ottoman soldiers; there may have been as many as 2,000, consisting of two battalions of the 80th Infantry Regiment (27th Ottoman Infantry Division but attached to the 3rd Ottoman Infantry Division for most of 1916). These two battalions, the 2nd Battalion, commanded by Izzet Bey, of about 600 men and the 3rd Battalion, commanded by Rushti Bey, were supported by a dismounted camel company and two squads from the 80th Machine Gun Company. (The remainder squads of the 80th Machine Gun Company had been moved north to Shellal.) The defending force was also supported by a battery of four Krupp 7.5 cm Gebirgskanone M 1873 guns (on loan from the 1st Mountain Regiment), since the 80th Regiment's own artillery battery was stationed at Nekhl. Also attached to the Ottoman garrison at Magdhaba were a number of support units, including elements of the 3rd Company of the 8th Engineer Battalion, 27th Medical Company, 43rd Mobile Hospital and the 46th Cooking Unit. The garrison was under the command of Kadri Bey, the commanding officer of the 80th Infantry Regiment.[37][38]

The series of six well-situated and developed redoubts making up the strong Ottoman garrison position at Magdhaba reflected considerable planning; the redoubts were almost impossible to locate on the flat ground on both sides of the Wadi el Arish. Clearly, the move of the Ottoman garrison from El Arish had not been a sudden, panicked reaction; indeed it was first noticed by Allied aerial reconnaissance planes as early as 25 October.[39][40]

These fortified redoubts, which were situated on both sides of the wadi, were linked by a series of trenches.[Note 7] The whole position, extending over an area of about 2 miles (3.2 km) from east to west, was more narrow from north to south. On 22 December 1916, the day before the attack, the garrison had been inspected by Kress von Kressenstein, commander of the Ottoman Desert Force, who drove from his base at Hafir el Auja. At the time he expressed satisfaction with the garrison's ability to withstand any assault.[4][41][Note 8]

Von Kressenstein's satisfaction that the garrison could withstand any assault may have had something to do with its remoteness. Magdhaba was about 40 miles (64 km) from the British railhead and 25 miles (40 km) from El Arish.[42] There were two other important pieces of information von Kressenstein did not have. Firstly, he would have been unaware of the speed, flexibility and determination of the Australian, British and New Zealand mounted force, which they were about to demonstrate. Secondly, the arrival of the new British commander, Chetwode, and his staff and their vital forward planning to organise the necessary logistical support for an immediate long range attack by the Anzac Mounted Division.[43]

British Empire force

Chauvel's force for the attack on Magdhaba consisted of three brigades of the Anzac Mounted Division; 1st Light Horse Brigade (1st, 2nd and 3rd Light Horse Regiments), the 3rd Light Horse Brigade (8th, 9th and 10th Light Horse Regiments), the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade (Auckland, Canterbury and Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiments), together with three battalions from the Imperial Camel Brigade in place of the 2nd Light Horse Brigade. These nine regiments and three battalions were supported by the Inverness and Somerset Artillery Batteries, Royal Horse Artillery, and the Hong Kong and Singapore Artillery Battery.[44][45][Note 9]

This force, which may have been 7,000 strong, moved out from El Arish just after midnight, following an unexpected delay caused by incoming infantry columns of the 52nd (Lowland) Division, which crossed the long camel train carrying water which followed the mounted division. Nevertheless, the Anzac Mounted Division (riding for forty minutes, dismounting and leading their horse for ten minutes and halting for ten minutes every hour) reached the plain 4 miles (6.4 km) from Magdhaba, at about 05:00 on 23 December. The column had been successfully guided by brigade scouts, until the garrison's fires had become visible for about an hour during their trek, indicating the Ottomans did not expect an attacking force to set out on a second night march, after their 30 miles (48 km) ride to El Arish.[35][41]

Aerial support

Aerial reconnaissances were routinely carried out; one carried out on 15 November by the Australian Flying Corps made a detailed reconnaissance behind enemy lines over the areas of El Kossaima, Hafir el Auja and Abu Aweigila, taking 24 photographs of all camps and dumps.[46]

The Royal Flying Corps's 5th Wing under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel P B Joubert de la Ferté stationed at Mustabig supported the Anzac Mounted Division. The Wing was a composite formation of the No. 14 Squadron and the Australian Flying Corps's No. 1 Squadron. It was ordered to provide close air support, long-range scouting and long-range bombing. One British and ten Australian planes had dropped a hundred bombs on Magdhaba on 22 December and during the battle bombed and machine gunned the area, but targets were difficult to find.[47][48]

Medical support

The evacuation of wounded had been reviewed following the problems encountered during the Battle of Romani, with particular attention given to the development of transport by railway. By the time the advance to El Arish occurred in December 1916, two additional hospital trains were available on the Sinai railway, and medical sections had been deployed at the following:

- close to the battlefield at railhead, where the immobile sections of divisional field ambulances could accommodation 700 casualties,

- at Bir el Abd No. 24 Casualty Clearing Station (CCS), which could accommodate 400 cases, and Nos. 53 and 54 CCS could each accommodate 200,

- at Bir el Mazar No. 26 CCS, which could accommodate 400 cases,

- at Mahamdiyah No. 2 (Australian) Stationary Hospital with 800 beds,

- at Kantara East No. 24 Stationary Hospital with 800 beds.[49]

Battle

At 06:30 the No. 5 Wing attacked the Ottoman defences, drawing some fire which revealed the locations of machine guns, trenches and five redoubts. The redoubts were arranged around the village, which protected the only available water supply in the area. During the day, pilots and their observers provided frequent reports; fourteen were received between 07:50 and 15:15, giving estimated positions, strength, and movements of the Ottoman garrison. These were most often given verbally by the observer, after the pilot landed near Chauvel's headquarters, as the aircraft did not at this time have wireless communication.[47][50]

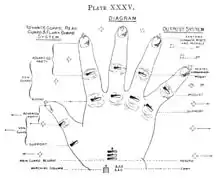

The main attack, from the north and east, was to be made by the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Edward Chaytor, which moved in line of troop columns. The New Zealanders were supported by a machine gun squadron armed with Vickers and Lewis guns, and the 3rd Light Horse Brigade all under the command of Chaytor. This attack began near the village of Magdhaba and the Wadi El Arish, on the virtually featureless battleground, when the British Empire artillery opened fire at the same time as Chaytor's group moved towards the Ottoman garrison's right and rear.[51][52]

Chauvel's plan of envelopment quickly began to develop.[53][54] Despite heavy Ottoman fire, Chaytor's attacking mounted troops found cover and dismounted, some about 1,600 yards (1,500 m) from the redoubts and entrenchments, while others got as close as 400 yards (370 m).[Note 10] At the same time, units of the Imperial Camel Brigade were moving straight on Magdhaba, in a south easterly direction, following the telegraph line, and by 08:45 were slowly advancing on foot, followed by the 1st Light Horse Brigade, in reserve.[51][52]

Chauvel's envelopment was extended at 09:25, when Chaytor ordered a regiment to circle the entrenched positions and move through Aulad Ali, to cut off a possible line of retreat to the south and south east. The 10th Light Horse Regiment with two sections of the brigade Machine Gun Squadron, led by Brigadier General J. R. Royston, commander of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade, succeeded in capturing Aulad Ali and 300 prisoners.[55]

The Ottoman artillery batteries and trenches were difficult to locate, but by 10:00 the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade was advancing towards the firing line. At this time, an aerial report described small groups of the Magdhaba garrison beginning to retreat, and as a result the still-mounted reserve, the 1st Light Horse Brigade, was ordered to move directly on the town, passing the dismounted Imperial Camel Brigade battalions on their way. After meeting severe shrapnel fire as they trotted over the open plain, they were forced to take cover in the Wadi el Arish where they dismounted, continuing their advance at 10:30 against the Ottoman left. Meanwhile, the battalions of the Imperial Camel Brigade, continued their advance over the flat ground for 900 yards (820 m), section by section, covering fire provided by each section in turn.[51]

By 12:00 all brigades were hotly engaged, as the 3rd Light Horse Brigade's 10th Light Horse Regiment continued their sweep round the garrison's right flank. An hour later, the right of the Imperial Camel Brigade battalions had advanced to reach the 1st Light Horse Brigade and 55 minutes afterwards, fierce fighting was beginning to make an impact on the Ottoman garrison. Reports continued of small numbers of Ottoman troops retreating, but by 14:15 the 10th Light Horse Regiment was continuing its trek after capturing Aulad Ali; moving across the Wadi el Arish, round Hill 345 to attack the rear of Redoubt No. 4. By 14:55 the frontal attack by the Imperial Camel Brigade was within 500 yards (460 m) of the Ottoman defences and, together with the 1st Light Horse Brigade, at 15:20, they attacked No. 2 redoubt. Ten minutes later the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade, with fixed bayonets, attacked the trenches to the east of some houses and the 10th Light Horse Regiment, by now advancing from the south, captured two trenches on that side, effectively cutting off any retreat for the Ottoman garrison.[52][56][57]

By 16:00 the 1st Light Horse Brigade had captured No. 2 redoubt, and Chaytor reported capturing buildings and redoubts on the left. After a telephone call between Chauvel and Chetwode, pressure continued to be exerted and an attack by all units took place at 16:30. The Ottoman garrison held on until the dismounted attackers were within 20 yards (18 m), but by that time, there was no doubt that the Ottoman garrison was losing the fight, and they began to surrender in small groups. All organised resistance ceased ten minutes later and as darkness fell, sporadic firing petered out, while prisoners were rounded up, horses collected and watered at the captured wells. Then Chauvel rode into Magdhaba and gave the order to clear the battlefield.[52][56][57]

At 23:30 the Anzac Mounted Division's headquarters left Magdhaba with an escort and arrived in El Arish at 04:10 on 24 December 1916.[53][58][59][Note 11]

Casualties and captures

Of the 146 known British Empire casualties, 22 were killed and 124 were wounded.[60] Five officers were killed and seven wounded, and 17 other ranks were killed and 117 wounded. Included in the 146 figure, which may have been as high as 163, the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade suffered the loss of two officers and seven other ranks killed and 36 other ranks wounded.[28][58][61]

No more than 200 Ottoman soldiers escaped before the surviving garrison of between 1,242 and 1,282 men were captured.[61][62] The prisoners included the 80th Regiment's commander Khadir Bey, and the 2nd and 3rd Battalions commanders, Izzat Bey, Rushti Bey among 43 officers. Over 300 Ottoman soldiers were killed; 97 were buried on the battlefield, and 40 wounded were cared for.[28][38][42][58]

Aftermath

With the victory at Magdhaba the occupation of El Arish was secure. This was the first town captured on the Mediterranean coast and infantry from the 52nd (Lowland) Division and the 5th Mounted Yeomanry Brigade quickly began to fortify the town. The Royal Navy arrived on 22 December 1916, and supplies began landing on the beaches near El Arish on 24 December. After the arrival of the railway on 4 January 1917 followed by the water pipeline, El Arish quickly developed into a major base for the EEF.[36][63]

Aerial reconnaissance found Ottoman forces moving their headquarters north from Beersheba, while the garrison at their main desert base of Hafir El Auja was slightly increased. Other Ottoman outposts at El Kossaima and Nekhl remained, along with their strong defensive system of trenches and redoubts at El Magruntein, defending Rafa, on the frontier between Egypt and the southern Ottoman Empire.[64][65]

Return to El Arish

Chauvel's force had left El Arish the previous night, carrying one water bottle per man.[59] Additional water was organised by Desert Column staff and sent from El Arish to Lahfan, and a water convoy from Lahfan, ordered to move to Magdhaba at 15:10 on the day of battle, was reported to be on its way at 15:20.[66]

After filling up from the water convoy after its arrival at Magdhaba, the New Zealand Mounted Rifles and 3rd Light Horse Brigades left to ride back to El Arish in their own time.[53][58][59]

Material assistance was given to the returning columns by the 52nd (Lowland) Division, in form of the loan of camels, water fantasses, sandcarts and gun horse teams, the latter going out on the commanding generals' initiative to meet the returning teams.[58][Note 12]

Clearing the battleground

At dressing station set up 3 miles (4.8 km) west of Magdhaba, by the New Zealand Field Ambulance Mobile Section and the 1st Light Horse Field Ambulance, 80 wounded were treated during the day of battle. Field ambulances performed urgent surgery, gave tetanus inoculations and fed patients. During the night after the battle, treated wounded were evacuated in sandcarts and on torturous cacolets to El Arish, with the No. 1 Ambulance Convoy assisting.[67][68][Note 13]

Part of the 1st Light Horse Regiment, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel C. H. Granville, with two squadrons of the Auckland Mounted Rifle Regiment, and one squadron from the 3rd Light Horse Brigade bivouacked for the night at Magdhaba. A convoy of supplies was ordered from El Arish to support these troops as they continued, the following morning, clearing the battlefield.[58][59] The remaining 44 British Empire and 66 Ottoman Empire wounded, collected on 23 and 24 December, were taken to an Ottoman hospital within the Magdhaba fortifications, before being sent to the dressing station. From there, at 17:00 the ambulance convoy set out on its 23 miles (37 km) march to the receiving station.[67][68]

The convoys of wounded were met a few miles from El Arish by infantry with sandcarts lent by the 52nd (Lowland) Division, so the wounded who had endured the cacolets travelled in comfort to the receiving station, arriving at 04:00 on 25 December. The 52nd (Lowland) Division supplied medical stores and personnel to assist, but although arrangements were made for evacuation to the railhead two days later, evacuation by sea was planned. This had to be postponed due to a gale with rain and hail on 27 December and it was not until 29 December that the largest single ambulance convoy organised in the campaign, 77 sandcarts, nine sledges and a number of cacolet camels, moved out in three lines along the beach with 150 wounded. A few serious cases, who had not been ready to be moved, were evacuated the following day to begin their journey to Kantara on the Suez Canal.[67][68]

Recognition

In an address to the troops after the battle, Chetwode expressed his appreciation for the mounted rifle and light horse method of attack. He said that in the history of warfare he had never known cavalry to not only locate and surround the opponent's position, but to dismount and fight as infantry with rifle and bayonet.[69]

On 28 September 1917 Chauvel, who by this time had been promoted by Allenby to command three mounted divisions in Desert Mounted Corps, wrote to General Headquarters:

The point is now that, during the period covered by Sir Archibald's Despatch of 1-3-17, the Australia and New Zealand Troops well know that, with the exception of the 5th Mounted [Yeomanry] Brigade and some Yeomanry Companies of the I.C.C., they were absolutely the only troops engaged with the enemy on this front and yet they see that they have again got a very small portion indeed of the hundreds of Honours and Rewards (including mentions in Despatches) that have been granted. My Lists when commanding the A. & N.Z. Mounted Division, were modest ones under all the circumstances and in that perhaps I am partly to blame but, as you will see by attached list, a good many of my recommendations were cut out and in some cases those recommended for decorations were not even mentioned in Despatches.

— Chauvel, letter to GHQ[70]

Notes

- Footnotes

- The Battles Nomenclature Committee assigned 'Affair' to those engagements between forces smaller than a division; 'Action' to engagements between divisions and 'Battle' to engagements between corps.[Battles Nomenclature Committee 1922 p. 7]

- El Kossaima has been described as railhead [Bruce 2002, p. 81] but Keogh's Map 3 shows railhead at Hafir el Auja. Both Wavell and Powles refer to 15 miles (24 km) of line being destroyed on 23 May 1917 on the railway from Beersheba to Auja [Hafir el Auja]. [Wavell 1968, p. 90, Powles 1922, pp. 110, 113]

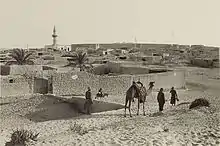

- See photo of Hafir el Auja below.

- See also Library of Congress Photograph Album, pp. 41–9

- Map 3 shows the position of Auja, Magdhaba and Beersheba.

- The names of the divisions, brigades and battalions and some other units have, in many cases, been changed so they no longer reflect the names of these units as they appear in some of the sources quoted.

- Falls indicates four redoubts on his Map 12 while Powles shows six on his map.

- Kress von Kressenstein has been criticised by English language historians for withdrawing his troops and leaving the garrison at Magdhaba isolated. [Bruce 2002 p. 83, Keogh 1955, p. 76–7]

- The Inverness battery alone is recorded as having fired 498 rounds during the action. [Falls 1930 Vol. 1, p. 258]

- While fighting dismounted, one quarter of the light horse and riflemen were holding the horses. [Preston 1921 p.168]

- Chauvel has been criticised for deciding to break off the action prematurely but before the order could reach the troops, by 16.30 the battle was won. [Hill 1978 p. 89, Grainger 2006, p. 4, Downes 1938, p. 592] He has also been criticised for withdrawing after the battle. [Bruce 2002 p. 84, Bou 2009, p. 158, Cutlack, 1941, p. 50]

- Fantasses were oblong metal containers carried by camels, one strapped on either side of the hump. [Carver, 2003 illustration No. 60 between pp. 186–7]

- Cacolets were contraptions tied to camels so that wounded could ride on them; either sitting up or lying down, one on either side of the hump. [See Photo]

- Citations

- Battles Nomenclature Committee 1922, p. 31

- Falls 1930, pp. 13–4, 28–50

- Keogh 1955, p. 56

- Kress von Kressenstein 1938, pp. 207–8

- Falls 1930 Vol. 1 pp. 245–6

- Powles 1922, p. 46

- Powles 1922, p. 47

- Keogh 1955, p. 71

- Falls 1930 Vol. 1, p. 85

- Kressenstein 1938 pp 207–8

- Keogh 1955, p.26 Map 3

- Downes 1938 pp. 555–6

- Downes 1938, p. 590

- Keogh 1955, p. 72

- Powles 1922, pp. 44–5

- Powles 1922, p. 66

- Keogh 1955 p. 62

- Bruce 2002, p. 79

- Wavell 1968, pp. 57–9

- Bruce 2002, p. 80

- Keogh 1955 p. 60

- Downes 1938 p. 589

- Hill 1978, p. 85

- Hill 1978, p. 86

- Falls 1930 Vol. 1, pp. 380–406

- Baker, Chris. "British Divisions of 1914–1918". The Long Long Trail. Archived from the original on 16 December 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- National Archives of Australia B2455 Chauvel H.G.; Statement of Service 18/12/1925; pp. 121–2

- Woodward 2003, p. 53

- AWM4/1/60/10 Anzac Mounted Division War Diary Appendix 24, p. 1 and Appendix 25 Sketch Map

- Falls 1930 Vol. 1, pp. 252–3, 271, 397

- Cutlack 1941, p. 48

- Falls 1930 Vol. 1, p. 251

- AWM4/1/60/10 Anzac Mounted Division War Diary Appendix 24, p. 2

- Keogh 1955, p. 74

- Powles 1922, p. 50

- Bruce 2002, p. 82

- Turkish General Staff 1979, p. 429

- Dennis et al 2008, p. 405

- Cutlack 1941, pp. 43–4

- Powles 1922, pp. 69–70

- Falls 1930 Vol., 1 p. 253

- Bruce 2002, p. 84

- AWM4/1/60/10 Anzac Mounted Division War Diary Appendix 24, p. 3

- Powles 1922, pp. 48–9 and Map of Magdhaba

- AWM4/1/60/10 Anzac Mounted Division War Diary Appendix 24, pp. 3–4 and Appendix 25 Sketch Map

- Cutlack 1941, p. 45-6

- AWM4/1/60/10 Anzac Mounted Division War Diary Appendix 24, pp. 3–8

- Cutlack 1941, pp. 45–9

- Falls 1930 Vol. 1 p. 274

- Powles 1922, p. 51

- AWM4/1/60/10 Anzac Mounted Division War Diary Appendix 24, p. 4

- Powles 1922, pp. 51–3

- Hill 1978, p. 89

- Bruce 2002, p. 83

- Falls 1930 Vol. 1, pp. 254, 256

- AWM4/1/60/10 Anzac Mounted Division War Diary Appendix 24, pp. 6–8

- Falls 1930 Vol. 1, pp. 254, 256–7

- AWM4/1/60/10 Anzac Mounted Division War Diary Appendix 24, p. 8

- Powles 1922, p. 54

- Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 122

- Powles 1922, pp. 55–6

- Cutlack 1941, p. 49

- Carver 2003, p.194

- Cutlack 1941, pp. 49–51

- Gullett 1941, p. 230

- AWM4/1/60/10 Anzac Mounted Division War Diary Appendix 24, p. 7

- Downes 1938, pp. 592–3

- Powles 1922, p. 61

- Powles 1922, p. 57

- Hill 1978, p. 122

References

- The Official Names of the Battles and Other Engagements Fought by the Military Forces of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914–1919, and the third Afghan War, 1919: Report of the Battles Nomenclature Committee as Approved by The Army Council Presented to Parliament by Command of His Majesty. London: Government Printer. 1922. OCLC 29078007.

- Bou, Jean (2009). Light Horse: A History of Australia's Mounted Arm. Australian Army History. Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19708-3.

- Bruce, Anthony (2002). The Last Crusade: The Palestine Campaign in the First World War. London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-5432-2.

- Carver, Michael, Field Marshal Lord (2003). The National Army Museum Book of The Turkish Front 1914–1918 The Campaigns at Gallipoli, in Mesopotamia and in Palestine. London: Pan Macmillan. ISBN 0-283-07347-0.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1998). Where Australians Fought: The Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles (1st ed.). St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-611-2.

- Cutlack, Frederic Morley (1941). The Australian Flying Corps in the Western and Eastern Theatres of War, 1914–1918. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Volume VIII. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 220899617.

- Dennis, Peter; Jeffrey Grey; Ewan Morris; Robin Prior; Jean Bou (2008). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History (2nd ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press, Australia & New Zealand. ISBN 978-0-19-551784-2.

- Downes, Rupert M. (1938). "The Campaign in Sinai and Palestine". In Butler, Arthur Graham (ed.). Gallipoli, Palestine and New Guinea. Official History of the Australian Army Medical Services, 1914–1918. Volume 1 Part II (2nd ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. pp. 547–780. OCLC 220879097.

- Falls, Cyril; G. MacMunn (1930). Military Operations Egypt & Palestine: From the Outbreak of War with Germany to June 1917. Official History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. 1. London: HM Stationery Office. OCLC 610273484.

- Grainger, John D. (2006). The Battle for Palestine, 1917. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-263-1.

- Gullett, Henry Somer (1941). The Australian Imperial Force in Sinai and Palestine, 1914–1918. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Volume VII. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 220900153.

- Hill, Alec Jeffrey (1978). Chauvel of the Light Horse: A Biography of General Sir Harry Chauvel, GCMG, KCB. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0-522-84146-6.

- Keogh, E. G.; Joan Graham (1955). Suez to Aleppo. Melbourne: Directorate of Military Training by Wilkie & Co. OCLC 220029983.

- Kress von Kressenstein, Friedrich Freiherr (1938). Mit den Tèurken zum Suezkanal. Berlin: Schlegel/Vorhut-Verl. OCLC 230745310.

- Powles, C. Guy; A. Wilkie (1922). The New Zealanders in Sinai and Palestine. Official History New Zealand's Effort in the Great War. Volume III. Auckland: Whitcombe & Tombs. OCLC 2959465.

- Preston, R. M. P. (1921). The Desert Mounted Corps: An Account of the Cavalry Operations in Palestine and Syria 1917–1918. London: Constable & Co. OCLC 3900439.

- Pugsley, Christoper (2004). The Anzac Experience: New Zealand, Australia and Empire in the First World War. Auckland: Reed Books. ISBN 0-7900-0941-2.

- Turkish General Staff (1979). Birinci Dünya Harbi'nde Turk harbi. Sina–Filistin cephesi, Harbin Başlangicindan İkinci Gazze Muharebeleri Sonuna Kadar. Sinai-Palestine Front from the beginning of the war to the end of the 2nd Gaza Battle, Volume 4, 1st Part. Ankara: IVncu Cilt 1nci Kisim.

- Wavell, Field Marshal Earl (1968) [1933]. "The Palestine Campaigns". In Sheppard, Eric William (ed.). A Short History of the British Army (4th ed.). London: Constable & Co. OCLC 35621223.

- Woodward, David R. (2006). Hell in the Holy Land: World War I in the Middle East. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2383-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Magdhaba. |

- "AWM4/1/60/10 Anzac Mounted Division War Diary". Canberra: Australian War Memorial. December 1916. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011.

- American Colony (Jerusalem) Photo Department (1914–1917). "World War I in Palestine and the Sinai Photo Album". Washington D. C.: The Library of Congress. OCLC 231653216.

- Australian Light Horse Studies Centre−

- El Arish and El Magdhaba

- Comparison of Maps – Australian, British and Turkish Histories