Battle of Vercors

The Maquis du Vercors was a rural group of the French Forces of the Interior (FFI) (maquis) that resisted the 1940–1944 German occupation of France in World War II. The Maquis du Vercors used the prominent scenic plateau known as the Massif du Vercors (Vercors Plateau) as a refuge. Initially the maquis carried out only sabotage and partisan operations against the Germans, but after the Normandy Invasion on 6 June 1944, the leadership of an army of about 4,000 maquis declared the "Free Republic of Vercors," raised the French flag, and attempted to create a conventional army to oppose the German occupation.

| Battle of Vercors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Vercors Massif | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Supported by | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

(36 aircraft operational)[3] | 4,000 maquisards | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

65 killed[4] 133 wounded[4] 18 missing[4] | 639 maquisards killed[4] | ||||||

|

201 civilians killed[4] 500 houses destroyed[5] | |||||||

The allies supported the maquis with parachute drops of weapons and by supplying teams of advisors and trainers, but the uprising was premature. In July 1944 as many as 10,000 German soldiers invaded the massif and killed more than 600 of the maquis, known as maquisards, and 200 civilians. It was German's largest anti-partisan operation in Western Europe during World War II.[6]

In August 1944, shortly after the battle for the Vercors, the area was liberated from German control by the American army allied with the French Forces of the Interior (FFI).

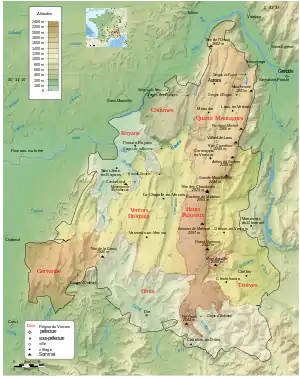

Geography

The Vercors Massif is a roughly triangular-shaped plateau with a maximum north–south length of 60 kilometres (37 mi) and a maximum width of 40 kilometres (25 mi). The area is 135,000 hectares (520 sq mi).[7] The lowlands surrounding the steep-sided plateau average about 250 metres (820 ft) in elevation above sea level while the top of the massif has an average elevation of about 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) with a maximum elevation of 2,341 metres (7,680 ft) at Grand Veymont.[8][9] Unlike a flat-topped mesa, three ridges run along the top of the massif from north to south. Only a few roads climb the steep slopes to access the massif and the population lives in a few small villages. The porous limestone rocks and karst terrain result in an extensive system of caves and caverns and a scarcity of surface water in the form of streams, springs, and shallow wells. These characteristics would be important during the battle as the Germans took control of the water sources and ambushed maquis seeking water.[10] [11]

The city of Grenoble, which had a large German military presence, is situated at the foot of the steep cliffs of the Vercors Massif at its northeastern edge. An important German air force base was located at Chabeuil, just below the southwestern rim of the Vercors.

Background

Paddy Ashdown, The Cruel Victory.

Beginning in 1942, the Service du Travail Obligatoire (STO) (Compulsory Work Service) resulted in the deportation of hundreds of thousands of young French men to Nazi Germany to work as labour for the German war effort. To avoid the STO tens of thousands of men fled to the mountains and forests of France and joined the maquis, the rural resistance fighters against the German occupation.[13] In 1943, three men, mountaineer Pierre Dalloz, soldier Alain Le Ray, and writer Jean Prévost developed a plan to use the Vercors as a redoubt and a staging area for resistance to the German occupation.[14] Following the German invasion of the "Free Zone" (Zone libre) and the disbandment of the Vichy Armistice Army, about fifty soldiers of the 11th Cuirassier Regiment arrived in the Vercors, but kept themselves distinct from the maquis, whom they regarded as amateurs.[15]

In August 1943, Francis Cammaerts, code named Roger, an agent of the United Kingdom's clandestine Special Operations Executive (S0E) organization, journeyed to the Vercors and met with French soldier Eugène Chavant. Cammaerts liked the Vercors plan. He foresaw the Vercors and other nearby mountainous areas as drop zones for allied paratroopers who would work with the local maquis to tie down German military forces and assist the Allied forces in the contemplated invasion of southern France (Operation Dragoon) which was then in the planning stages. Cammaerts arranged for the first airdrop of arms and supplies by the SOE to the Vercors maquis on 13 November 1943. On January 6, 1944, a three-man "Union" mission, including US Marine Peter Ortiz from the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS), Colonel Pierre Fourcaud, of the French secret service, and Harry Thackthwaite of the SOE, to evaluate the capabilities of the Resistance in the Alpine region of France. Along with Cammaerts they organized, trained, and armed the maquis to prepare them for an important role in support of the allied invasion of southern France. The Union group departed France in May 1944.[16]

The Germans had no soldiers stationed on the Vercors Massif, but in response to sabotage activities of the maquis conducted periodic raids usually launched from Grenoble. The first raid was on 25 November 1943 and resulted in a wireless operator captured and another wounded.[17] On 22 January 1944, a column of 300 German troops arrived at the Grands Goulets gorge on a punitive expedition in retaliation for the ambush of a German staff car a few days earlier. A small force of maquisards attempted to block their progress on the narrow road but were either outgunned or outflanked by Gebirgsjäger Alpine troops at each blocking position that they established; twenty maquis were killed. When the Germans reached Échevis on the plateau, they burned the village.[18] The Germans also used the Milice (a pro-German French paramilitary militia) to suppress the growing strength of the resistance on the Vercors massif. On April 15, 1944 a caravan of 25 Milice vehicles attacked the village of Vassieux, burning several farms and shooting or deporting some of the inhabitants.[19]

Mixed signals

In the weeks leading up to the invasion of Normandy (D-Day) on 6 June 1944, the guidance and instructions given by the Allies to the maquis on the Vercors Massif were contradictory and inconsistent. One issue was whether the maquis should rise in armed opposition to the Germans immediately after D-Day or wait until later when they could be of maximum help to the allies. The contradictions are illustrated by the differences in the D-Day messages of allied commander Dwight D. Eisenhower and Free French leader Charles de Gaulle. Eisenhower urged all the maquis in France to be cautious and patient; De Gaulle's emotional message was interpreted by the maquis as a call to take up arms immediately. On D-Day, Cammaerts on the Vercors Massif, gave the message to the maquis that, while clandestine sabotage should continue, they should remain hidden as "it would be at least two months before they would be needed." Cammaerts knew also that similar uprisings in other areas had been crushed by the Germans. To the contrary on June 8, Marcel Descour, the regional leader of the French Resistance, instructed Francois Huet, the newly named commander of the Vercors marquis, to mobilize. When Huet objected that he had neither the men nor the arms to defend Vercors, Descour assured him that the allies would send reinforcements. [20]

The expectations of the Vercors maquis were that the invasion of southern France would be shortly after D-Day, when in reality it took place more than two months later. The maquis also anticipated incorrectly that allied paratroopers would land on the massif to assist them and that they would be supplied with anti-tank and other heavy weapons to fight the Germans.[21] "We shall not forget the bitterness of having been abandoned alone and without support in time of battle," wired the FFI commander to London.[22] The priorities of the allied forces were the Normandy front and the upcoming Operation Dragoon landing in Southern France, not the maquis of Vercors.[23]

German attacks

Peter Lieb, Vercors 1944.

German repression of the maquis on the Vercors Massif began on 11 June with a reconnaissance-in-force from the city of Grenoble to the village of Saint-Nizier-du-Moucherotte. The small German force was repulsed by the maquis controlling the only road leading up the massif to Saint-Nizier. On 15 June the Germans returned with artillery and a larger force and forced the maquis to withdraw. During the remainder of June, the Germans sent several more probing attacks onto the Vercors. The allies parachuted arms and supplies to the maquis on 27 June and the allies sent two teams to help them: An OSS team of 15 American soldiers commanded by Lt. Vernon G. Hoppers and a four-man SOE team headed by Major Desmond Longe. Longe spoke little or no French and Cammaerts took offense at the unannounced arrival of Longe's team, calling them "unprofessional voyeurs" and asserting his authority as the senior British official on the ground in southeastern France.[25]

Free Republic of Vercors

While François Huet was attempting to create a conventional army from the maquis, journalist and De Gaulle supporter Yves Farge was organizing the politics of the Vercors resistance. On 3 July 1944 Farge and a committee proclaimed the founding of the Free Republic of Vercors, the first independent territory in France since the beginning of the German occupation in 1940. The Free Republic had its own flag, i.e., the French Republic tricolour featuring the Cross of Lorraine and the "V" for Vercors and Victory (both used as a signature by General Charles de Gaulle's Free French Forces), and its coat of arms, the French Alpine Chamois. It was a short-lived republic; it ceased to exist before the end of the month.[26][27]

Bastille Day

On 14 July, 72 American B-17's dropped by parachute 870 CLE Canisters containing weapons, including anti-tank bazookas, and supplies to the Maquis of Vercors. It was a daylight drop and the Germans quickly detected it and launched air strikes to bomb the canisters, the maquis attempting to recover them, and the village of Vassieux, destroying one-half of the 85 houses in the village. Working with the maquis to collect the canisters was a newly arrived SOE courier, Christine Granville (Krystyna Skarbek), "World War II's most glamorous spy."[28] [29]

The large, daytime drop of weapons, instead of the usual smaller night drops, were criticized by the maquis leaders as igniting German worries that the Vercors would become a serious threat to their forces and lines of communications. The German response was to organize one of their largest anti-resistance military operations in France during World War II.[30]

Battle

German Lt. General Karl Ludwig Pflaum was the commander of the German forces attacking the Vercors maquis. With eight to ten thousand soldiers, Pflaum established a cordon of soldiers around the massif to prevent the escape of maquis and on 21 July launched a full-scale attack. German columns advanced south along a road from Saint-Nizier in the northeast and from the south along a road from the town of Die. Alpine troops crossed the formidable, but thinly defended, eastern ramparts of the massif. The preparations being made for these assaults were readily visible to the maquis; the surprise element in the offensive was the landing of 200 airborne soldiers by glider near the village of Vassieux in the rear of the maquis defense. The glider landings were supported by warplanes bombing and strafing maquis positions.[31]

By that first evening it was clear that the German assault was succeeding. The maquis commander Huet had a meeting of his leaders and they decided to continue to fight until defeat was inevitable and then disperse to the forest and mountains of the massif, anticipating that the Germans would soon withdraw. It was also decided that Huet's superior officer in the FFI, Henri Zeller who was present at the meeting, would escape the Vercors with SOE agents Cammaerts, Granville, and wireless operator Auguste Floiras to coordinate the resistance in other areas. The maquis sent a bitter message to the Free French authorities in Algiers and to the SOE in London telling them that they were "criminals and cowards" for not sending help.[32]

The last gasps of the organized resistance were on 23 July with the surviving maquis taking refuge in the forests or escaping to the lowlands surrounding the Vercors. The American team led by Hoppers and the SOE team led by Longe both escaped. Huet hid in the forests until 6 August when he attempted to rally his surviving forces and, reverting to guerilla tactics, on 8 August the maquis carried out several raids, claiming they killed 27 Germans. The long-expected allied landing in southern France took place on 15 August and the allied forces advanced rapidly northward, aided by the maquis. On 22 August the city of Grenoble was liberated from German control and maquis from the Vercors marched in the victory parade.[33]

Casualties among the maquis during the battle were heavy with estimates of 659 maquis fighters and 201 civilians killed. German losses were 65 killed and 18 missing.[34]

German order of battle

According to the order of battle of 8 July 1944 from General Niehoff, Kommandant des Heeresgebietes Südfrankreich (military region of southern France), about operation Bettina against Maquis du Vercors, it appears that the Germans deployed nearly 10,000 soldiers and policemen under General Karl Pflaum:[35] Almost all the 157. Reserve-Division of the Wehrmacht:[2] 4 reserve mountain light infantry battalions (Btl. I./98, II./98, 99 and 100 from the Reserve-Gebirgsjäger-Regiment 1); 2 reserve infantry battalions (Btl. 179 and 199 from the Reserve-Grenadier-Regiment 157 – Btl. 217 remained in the southern Alps at Embrun); 2 reserve artillery batteries (from Res.Geb.Art.Abt. 79 out of the Reserve-Artillerie-Regiment 7).[36]

Other units: Kampfgruppe "Zabel" (1 infantry battalion from the 9. Panzer-Division and 1 Ost-Bataillon); 3 Ost-Bataillonen (Ostlegionen); about 200 Feldgendarmen; 1 security battalion (I./Sicherungs-Regiment 200); 1 police battalion (I./SS-Polizei-Regiment 19); about 400 paratroopers (special units from Fallschirm-Kampfgruppe Schäfer[37]).

According to the daily reports of OB West on 23 and 24 July 1944, forwarded by the Militärbefehlshaber in Frankreich, the following troops landed at Vassieux-en-Vercors on 21 and 23 July 1944:[38]

On 21 July 1944 about 200 men from Fallschirmjäger-Bewährungstruppe (probationary troops) forming the Fallschirm-Kampfgruppe "Schäfer",[37] with several French volunteers (from the Sipo-SD of Lyons or from the 8th company of the 3rd regiment "Brandenburg"), were airborne in 22 DFS-230 gliders (each with 1 pilot and 9 soldiers) towed by bombers Dornier-17 out of I/Luftlandegeschwader 1, from Lyons-Bron to Vassieux-en-Vercors.[39] According to Peter Lieb, two gliders crashed and eight of them landed a bit further on, so the first wave of assault consisted only of about a hundred soldiers.[40]

Peter Lieb spécifies that the commander of the Sipo-SD of Lyon (KDS), SS-Obersturmbannführer (SS Lieutenant Colonel) Werner Knab, was also airborne on Vassieux on 21 July. Shot and wounded, he was evacuated in a Fieseler Fi 156 Storch on 24 July. He would have played an important part in the torture and the slaughter of the Maquisards of Vercors and the inhabitants of Vassieux.[40]

On 23 July 1944, 3 Go-242 gliders (each with 2 pilots and 21 soldiers, or weaponry and supplies) towed by Heinkel-111 bombers, and 20 DFS-230 gliders[39] transported one Ost-Kompanie (Ostlegionen: Russian, Ukrainian and Caucasian volunteers) and a paratrooper platoon[38] from Valence-Chabeuil to Vassieux. According to Peter Lieb, at least two DFS-230 and two Go-242 gliders landed a further on, only one Go-242 with weaponry and supplies landed on Vassieux, so the second wave of assault consisted only of about a hundred and fifty soldiers.[40]

Thomas and Ketley[37] wrote that the Fallschirm-Kampfgruppe "Schäfer" was detached from Kampfgeschwader 200 on 8 June 1944. It was made up of volunteers out of Fallschirmjäger-Bewährungstruppe (probationary troops), mustered at Tangerhütte and trained for three months at Dedelstorf in order to launch an attack from gliders. Günther Gellermann says that the Fallschirm-Kampfgruppe "Schäfer" was under Luftflotte 3 command and no longer under Kampfgeschwader 200 command.[41]

In fiction

The Maquis du Vercors is depicted and veterans act in Pierre Schoendoerffer's 2002 feature film Above the Clouds (Là-Haut), and in the third season of the British TV programme Wish Me Luck, which first aired in 1990. The battle and the maquisards of Vercors also prominently feature in Frank Yerby's 1974 novel The Voyage Unplanned.

Documentary film

French director Jean-Paul Le Chanois made ''Au coeur de l'orage'' (In the Heart of the Thunderstorm), a documentary about the French Resistance during the Second World War, in 1948. The movie, composed of Allied clandestine film recordings and German newsreels, focuses on the battle of the Vercors Plateau during July 1944.[42]

In 2011 the Belgian TV channels RTBF and VRT broadcast a documentary film by André Bossuroy, addressing the memory of the victims of Nazism and of Stalinism ICH BIN, with support from the Fondation Hippocrène and from the EACEA Agency of the European Commission (Programme Europe for citizens – An active European remembrance), RTBF, VRT. Four young Europeans meet with historians and witnesses of our past... They investigate the events of the Second World War in Germany (the student movement of the White Rose in Munich), in France (the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup in Paris, the resistance in Vercors) and in Russia (Katyn Forest massacre).

See also

Citations

- Lieb 2012, p. 24.

- Lieb 2012, p. 29.

- Lieb 2012, p. 21.

- Lieb 2012, p. 71.

- Lieb 2012, p. 70.

- Ashdown, Paddy (2014). The Cruel Victory. London: William Collins. p. 277. ISBN 9780007520817.

- Ribard, Francois (2009). A la devouverte du Vercors: Parc naturel regional. Grenoble: Glenat. pp. 23–24. ISBN 9782723458498.

- Le Grand Veymont, Peakbagger.com, retrieved 27 February 2012

- Google Earth

- Ashdown 2014, pp. 6-7.

- Lieb 2012, pp. 69-70.

- Ashdown 2014, p. 19.

- Olson, Lynne (2017). Last Hope Island. New York: Random House. p. 219. ISBN 9780812997354.

- Ashdown 2014, pp. 31-36.

- Ashdown 2014, p. 29.

- Ashdown 2014, pp. 63-74, 150, 368.

- Ashdown2014, p. 75.

- Ashdown2014, p. 97.

- Ashdown2014, pp. 134-137.

- Ashdown 2014, pp. 152-159, 170, 177-179, 183.

- Ashdown 2014, pp. 165, 190-191.

- Richard Harris Smith (1972). OSS: The Secret History of America's First Central Intelligence Agency. University of California Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-520-02023-8.

- Lieb 2012, p. 67.

- Lieb, Peter (2012). Vercors 1944. Botley, Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 25. ISBN 9781849086998.

- Ashdown 2014, pp. 192-216, 220-221, 244-246.

- The Vercors in History through a few dates – Vercors Memorial website

- Ashdown 2014, pp. 247-248, 252-253.

- Garmen, Emma, "World War II's Most Glamorous Spy," , accessed 3 Jan 2020

- Ashdown 2014, pp. 169-176.

- Ashdown 2014, pp. 269-283.

- Ashdown 2014, pp. 279-310.

- Ashdown 2014, pp. 310-312.

- Ashdown 2014, pp. 336-338, 340, 343, 357-358.

- Ashdown 2014, p. 355.

- Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv RW 35/47

- Georg Tessin, "Verbände und Truppen der deutschen Wehrmacht und Waffen-SS im Zweiten Weltkrieg 1939 – 1945"

- Geoffrey J. Thomas and Barry Ketley, KG 200: The Luftwaffe’s Most Secret Unit, Hikoki Publications Ltd, Crowborough (East Sussex), 2003

- NARA T78 Roll 313

- Georg Schlaug, Die deutschen Lastensegler-Verbände 1937–1945, Motorbuch Verlag, 1985

- Peter Lieb, Vercors 1944. Resistance in the French Alps, Osprey, Oxford, 2012

- Günther W. Gellermann, "Moskau ruft Heeresgruppe Mitte: Was nicht im Wehrmachtbericht stand - Die Einsätze des geheimen Kampfgeschwaders 200 im Zweiten Weltkrieg", Bernard & Graefe, Koblenz, 1988

- IMDb - Au coeur de l'orage (1948) - https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0242291/

Bibliography

- Ashdown, Paddy (2014). The Cruel Victory. London: William Collins. ISBN 9780007520817.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lieb, Peter (2012). Vercors 1944: Resistance in the French Alps. Oxford: McFarland. ISBN 978 1 84908 698 1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

.svg.png.webp)