Book of Jubilees

The Book of Jubilees, sometimes called Lesser Genesis (Leptogenesis), is an ancient Jewish religious work of 50 chapters, considered canonical by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church as well as Beta Israel (Ethiopian Jews), where it is known as the Book of Division (Ge'ez: መጽሐፈ ኩፋሌ Mets'hafe Kufale). Jubilees is considered one of the pseudepigrapha by Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Eastern Orthodox Churches.[1] It is also not considered canonical within Judaism outside of Beta Israel.

| |||||

| Tanakh (Judaism) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Old Testament (Christianity) | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Bible portal | |||||

It was well known to Early Christians, as evidenced by the writings of Epiphanius, Justin Martyr, Origen, Diodorus of Tarsus, Isidore of Alexandria, Isidore of Seville, Eutychius of Alexandria, John Malalas, George Syncellus, and George Kedrenos. The text was also utilized by the community that originally collected the Dead Sea Scrolls. No complete Greek or Latin version is known to have survived, but the Ge'ez version has been shown to be an accurate translation of the versions found in the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The Book of Jubilees claims to present "the history of the division of the days of the Law, of the events of the years, the year-weeks, and the jubilees of the world" as revealed to Moses (in addition to the Torah or "Instruction") by angels while he was on Mount Sinai for forty days and forty nights.[2] The chronology given in Jubilees is based on multiples of seven; the jubilees are periods of 49 years (seven "year-weeks"), into which all of time has been divided.

Manuscripts

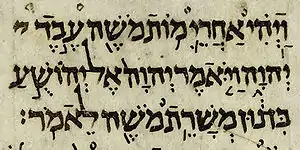

Until the discovery of extensive fragments among the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS), the only surviving manuscripts of Jubilees were four complete Ge'ez texts dating to the 15th and 16th centuries, and several quotations by the Church fathers such as Epiphanius, Justin Martyr, Origen as well as Diodorus of Tarsus, Isidore of Alexandria, Isidore of Seville, Eutychius of Alexandria, John Malalas, George Syncellus, and George Kedrenos. There is also a preserved fragment of a Latin translation of the Greek that contains about a quarter of the whole work.[3] The Ethiopic texts, now numbering twenty-seven, are the primary basis for translations into English. Passages in the texts of Jubilees that are directly parallel to verses in Genesis do not directly reproduce either of the two surviving manuscript traditions.[4] Consequently, even before the Qumran discoveries, R.H. Charles had deduced that the Hebrew original had used an otherwise unrecorded text for Genesis and for the early chapters of Exodus, one independent either of the Masoretic text or of the Hebrew text that was the basis for the Septuagint. According to one historian, the variation among parallel manuscript traditions that are exhibited by the Septuagint compared with the Masoretic text, and which are embodied in the further variants among the Dead Sea Scrolls, demonstrates that even canonical Hebrew texts did not possess any single "authorized" manuscript tradition in the first centuries BC.[5] Others write about the existence of three main textual manuscript traditions (namely the Babylonian, Samarian and Pre-Masoretic "proto" textual traditions). Although the Pre-Masoretic text may have indeed been authoritative back then, arguments can be made for and against this concept.[6]

Between 1947 and 1956, approximately 15 Jubilees scrolls were found in five caves at Qumran, all written in Hebrew. The large number of manuscripts (more than for any biblical books except for Psalms, Deuteronomy, Isaiah, Exodus, and Genesis, in descending order) indicates that Jubilees was widely used at Qumran. A comparison of the Qumran texts with the Ethiopic version, performed by James VanderKam, found that the Ethiopic was in most respects an accurate and literalistic translation.[7]

Origins

Robert Henry Charles (1855–1931) became the first biblical scholar to propose an origin for Jubilees. Charles suggested that the author of Jubilees may have been a Pharisee and that Jubilees was the product of the midrash which had already been worked on in the Tanakh/Old Testament Books of Chronicles.[3] With the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) at Qumran in 1947, Charles' Pharisaic hypothesis of the origin of Jubilees has been almost completely abandoned.

The dating of Jubilees has been problematic for biblical scholars. While the oldest extant copies of Jubilees can be assigned on the basis of the handwriting to about 100 BC, there is much evidence to suggest Jubilees was written prior to this date.[8]

Jubilees could not have been written very long prior. Jubilees at 4:17-25 records that Enoch "saw in a vision what has happened and what will occur", and the book contains many points of information otherwise found earliest in the Enochian "Animal Apocalypse" (1 Enoch chapters 83-90), such as Enoch's wife being Edna.[9] The Animal Apocalypse claims to predict the Maccabean Revolt (which occurred 167-160 BC) and is commonly dated to that time.[10] The direction of dependence has been controversial,[11] but the consensus since 2008 has been that the Animal Apocalypse came first and Jubilees after.[12]

As a result, general reference works such as the Oxford Annotated Bible and the Mercer Bible Dictionary conclude the work can be dated to 160–150 BC.[13]

Subsequent use

The Hasmoneans adopted Jubilees immediately, and it became a source for the Aramaic Levi Document.[14] Jubilees remained a point of reference for priestly circles (although they disputed its calendric proposal), and the Temple Scroll and "Epistle of Enoch" (1 Enoch 91:1–10, 92:3–93:10, 91:11–92:2, 93:11–105:3) are based on Jubilees.[15] It is the source for certain of the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, for instance that of Reuben.[16]

There is no official record of it in Pharisaic or Rabbinic sources. It was among several books that the Sanhedrin left out when the Bible was canonized. Sub rosa, many of the traditions which Jubilees includes for the first time, are echoed in later Jewish sources, including some 12th-century midrashim which may have had access to a Hebrew copy. The sole exception within Judaism, the Beta Israel Jews formerly of Ethiopia, regard the Ge'ez text as canonical.[17]

It appears that early Christian writers held the book of Jubilees in high regard, as many of them cited and alluded to Jubilees in their writing.[18]

Jan van Reeth argues that the Book of Jubilees had great influence on the formation of Islam.[19] In the Book of Jubilees there is the very same concept of revelation as in Islam: God's words and commandments are eternally written on celestial tablets. An angel reveals their content to a prophet (2, 1; 32, 21 f.). Abraham's role in the Book of Jubilees corresponds to Abraham's role in the Quran in more than one way. The interpretation of biblical figures as prophets is also rooted in the Book of Jubilees. Also numerology, the emphasis on angels, and the symbolism of anniversaries found their way into Islam, such as the fact that many important events in the prophet's biography as presented by Ibn Ishaq happen on the same date.

Etsuko Katsumata, comparing the Book of Jubilees and the Quran, notices significant differences, especially in Abraham's role in the quranic narrative, concluding that "the Book of Jubilees contains no passages in which Abraham disparages idols, as in the other texts, using tactics to make it look as if an idol has destroyed other idols (like in the Quran). The Book of Jubilees contains none of this kind of attitude; Abraham simply and directly destroys idols by setting fire to them."[20] The quranic Abraham-narrative, according to Katsumata, contains passages other than those in the Book of Jubilees in which Abraham is involved in disputes about idolatry.[21] Abraham in the Quran acts as a perserverant prophet with an active and confronting missionary character, especially to his father, who is throughout the narrative hostile towards his son.[22] Abraham tries to convince local people, leader and a king while not leaving his homeland. In the Book of Jubilees Abraham's role differs significantly; he has a favourable relationship to his father and leaves his home country after secretly burning down a temple.[23]

Content

Jubilees covers much of the same ground as Genesis, but often with additional detail, and addressing Moses in the second person as the entire history of creation, and of Israel up to that point, is recounted in divisions of 49 years each, or "Jubilees". The elapsed time from the creation, up to Moses receiving the scriptures upon Sinai during the Exodus, is calculated as fifty Jubilees, less the 40 years still to be spent wandering in the desert before entering Canaan – or 2,410 years.

Four classes of angels are mentioned: angels of the presence, angels of sanctifications, guardian angels over individuals, and angels presiding over the phenomena of nature. Enoch was the first man initiated by the angels in the art of writing, and wrote down, accordingly, all the secrets of astronomy, of chronology, and of the world's epochs. As regards demonology, the writer's position is largely that of the deuterocanonical writings from both New and Old Testament times.

The Book of Jubilees narrates the genesis of angels on the first day of Creation and the story of how a group of fallen angels mated with mortal females, giving rise to a race of giants known as the Nephilim, and then to their descendants, the Elioud. The Ethiopian version states that the "angels" were in fact the disobedient offspring of Seth (Deqiqa Set), while the "mortal females" were daughters of Cain.[24] This is also the view held by Clementine literature, Sextus Julius Africanus, Ephrem the Syrian, Augustine of Hippo, and John Chrysostom among many early Christian authorities. Their hybrid children, the Nephilim in existence during the time of Noah, were wiped out by the great flood. Jubilees also states that God granted ten percent of the disembodied spirits of the Nephilim to try to lead mankind astray after the flood.

Jubilees makes an incestuous reference regarding the son of Adam and Eve, Cain, and his wife. In chapter iv (1–12) (Cain and Abel), it mentions that Cain took his sister Awan to be his wife and Enoch was their child. It also mentions that Seth (the third son of Adam and Eve) married his sister Azura.[25]

According to this book, Hebrew is the language of Heaven, and was originally spoken by all creatures in the Garden, animals and man; however, the animals lost their power of speech when Adam and Eve were expelled. Following the Deluge, the earth was apportioned into three divisions for the three sons of Noah, and his sixteen grandsons. After the destruction of the Tower of Babel, their families were scattered to their respective allotments, and Hebrew was forgotten, until Abraham was taught it by the angels.

Jubilees also contains a few scattered allusions to the Messianic kingdom. Robert Henry Charles wrote in 1913:

This kingdom was to be ruled over by a Messiah sprung, not from Levi—that is, from the Maccabean family—as some of his contemporaries expected—but from Judah. This kingdom would be gradually realized on earth, and the transformation of physical nature would go hand in hand with the ethical transformation of man until there was a new heaven and a new earth. Thus, finally, all sin and pain would disappear and men would live to the age of 1,000 years in happiness and peace, and after death enjoy a blessed immortality in the spirit world.[3]

Jubilees insists (in Chapter 6) on a 364 day yearly calendar, made up of four quarters of 13 weeks each, rather than a year of 12 lunar months, which it says is off by 10 days per year (the actual number being about 11¼ days). It also insists on a "Double Sabbath" each year being counted as only one day to arrive at this computation.

Jubilees 7:20–29 is possibly an early reference to the Noahide laws.[26]

Sources

Jubilees bases its take on Enoch on the "Book of Watchers", 1 Enoch 1–36.[27]

Its sequence of events leading to the Flood match those of the "Dream Visions", 1 Enoch 83–90.

Notes

- Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.

- Book of Jubilees "Jublees 1:4"

- R. H. Charles (1913). "The Book of Jubilees". The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Archived from the original on February 24, 2009 – via Wesley Center Online.

- "A minute study of the text shows that it attests an independent form of the Hebrew text of Genesis and the early chapters of Exodus. Thus it agrees with individual authorities such as the Samaritan or the LXX, or the Syriac, or the Vulgate, or the Targum of Onkelos against all the rest. Or again it agrees with two or more of these authorities in opposition to the rest, as for instance with the Massoretic and Samaritan against the LXX, Syriac and Vulgate, or with the Massoretic and Onkelos against the Samaritan, LXX, Syriac, and Vulgate, or with the Massoretic, Samaritan and Syriac against the LXX or Vulgate." R.H. Charles, "7. Textual Affinities"[3]

- Robin Lane Fox, a classicist and historian, discusses these multifarious sources of Old and New Testaments in layman's terms in Unauthorized Version (1992).

- Hershel Shanks, an historian and archaeological scholar, provides various articles that explore this issue in great depth, from various experts in the field of Dead Sea Scrolls research, in his book Understanding the Dead Sea Scrolls: A Reader from the Biblical Archaeology Review, June 29, 1993"

- VanderKam, "The Book of Jubilees" in L. H. Schiffman and J. C. VanderKam (eds.), Encyclopedia of the Dead Sea Scrolls, Oxford University Press (2000), Vol. I, p. 435.

- VanderKam (1989, 2001), p.18; Gabriele Boccaccini (1998). Beyond the Essene Hypothesis. Eerdmans., 86f.

- Todd Russell Hanneken (2008). The Book of Jubilees Among the Apocalypses., 156.

- Boccaccini, 81f. Philip L.Tite. "Textual and Redactional Aspects of the Book of Dreams (1 Enoch 83-90)". Biblical Theology Bulletin. 31: 106f.. Independently of one another.

- Kugel, 252, n.37; Hanneken, 143.

- Daniel C Olson (2013). A New Reading of the Animal Apocalypse of 1 Enoch: All Nations Shall Be Blessed" / With a New Translation and Commentary". Brill. pp. 108–9 n. 63.

- VanderKam (1989, 2001), pp. 17–21.

- Kugel, 167

- Boccacini 99–101, 104–113 respectively

- Kugel, 110

- Wolf Leslau, Falasha Anthology (Yale 1951), xxvii, xxxviii, xlii, 9

- Charles, R. H. (1902). The book of Jubilees or the Little Genesis. London: Adam and Charles Black. pp. lxxvii–lxxxvi.

- Jan M.F. van Reeth (1992). Cf. also: Klaus Berger, Die Urchristen (2008) p. 340; Andrew Rippin, Roberto Tottoli (Hrsg.), Books and Written Culture of the Islamic World: Studies Presented to Claude Gilliot on the Occasion of his 75th Birthday, Brill (2015) p. 280 ff.

- Katsumata (2012).

- Katsumata (2012), pp. 51–52.

- Katsumata (2012), p. 54, "The Quran has many passages in which Abraham expounds the errors in idolatry. In these passages, Abraham always addresses his words to local people, and he does not leave their land. This probably reflects Islam’s position that aims at converting idol worshippers to monotheistic religion and settling in their place of residence."

- Katsumata (2012), pp. 52–54.

- Ethiopian Orthodox Church's canonical Amharic version of Jubilees, 5:21 – readable on p. 14 of this file. Archived 2011-06-14 at the Wayback Machine

- "Book of Jubilees". virtualreligion.net.

- "JUBILEES, BOOK OF - JewishEncyclopedia.com". jewishencyclopedia.com.

- Gabriele Boccacini, Beyond the Essene Hypothesis (Eerdmans: 1998)

References

- Martin Jr. Abegg. The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible. San Francisco, CA: HarperCollins, 1999. ISBN 0-06-060063-2.

- Matthias Albani, Jörg Frey, Armin Lange. Studies in the Book of Jubilees. Leuven: Peeters, 1997. ISBN 3-16-146793-0.

- Chanoch Albeck. Das Buch der Jubiläen und die Halacha Berlin: Scholem, 1930.

- Robert Henry Charles. The Ethiopic Version of the Hebrew Book of Jubilees. Oxford: Clarendon, 1895.

- Robert Henry Charles. The Book of Jubilees or the Little Genesis, Translated from the Editor's Ethiopic Text, and Edited with Introduction, Notes, and Indices (London: 1902).

- Gene L. Davenport. The Eschatology of the Book of Jubilees (SPB 20) Leiden: Brill, 1971.

- Albert-Marie Denis. Concordance latine du Liber Jubilaeorum sive parva Genesis (Informatique et étude de textes 4; Louvain: CETEDOC, 1973)

- August Dillmann. "Mashafa kufale sive Liber Jubilaeorum... aethiopice". Kiel, and London: Van Maack, Williams &Norgate, 1859.

- August Dillmann, and Hermann Rönsch. Das Buch der Jubiläen; oder, Die kleine Genesis. Leipzig: 1874.

- John C. Endres. Biblical Interpretation in the Book of Jubilees (Catholic Biblical Quarterly Monograph Series 18) Washington: Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1987. ISBN 0-915170-17-5.

- Katsumata, Etsuko (2012). "Abraham the Iconoclast: Different Interpretations in the Literature of the Second Temple Period, the Texts of Rabbinic Judaism, and the Quran". Journal of the Interdisciplinary Study of Monotheistic Religions (JISMOR). 8: 37–58.

- James L. Kugel, A walk through Jubilees : studies in the Book of Jubilees and the world of its creation, (Brill Academic Publishers, 2012); ISBN 978-900421768-3

- Jan M.F. van Reeth (1992). "Le Prophète musulman en tant que Nâsir Allâh et ses antécédents: le "Nazôraios" évangélique et le livre des jubilés". Orientalia Lovaniensia Periodica (OLP). 23: 251–274.

- Michael Segal. The Book of Jubilees: Rewritten Bible, Redaction, Ideology and Theology. Leiden-Boston, 2007. ISBN 978-90-04-15057-7.

- Michel Testuz. Les idées religieuses du livre des Jubilés Geneva: Droz, 1960.

- James C. VanderKam. Textual and Historical Studies in the Book of Jubilees (Harvard Semitic monographs, no. 14) Missoula: Scholars Press, 1977.

- James C. VanderKam. The Book of Jubilees. A Critical Text. Leuven: Peeters, 1989. ISBN 978-90-429-0551-1.

- James C. VanderKam. The Book of Jubilees. Translation. Leuven: Peeters, 1989. ISBN 978-90-429-0552-8.

- James C. VanderKam. The Book of Jubilees (Guides to Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha). Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001. ISBN 1-85075-767-4. ISBN 978-1-85075-767-2.

- Orval S. Wintermute, "Jubilees", in Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, ed. James H. Charlesworth (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1985) 2:35–142

External links

- The text translated by R.H. Charles, 1902, with introduction and notes.

- Jewish Encyclopedia entry

- The Catholic Encyclopedia view

- Development of the Canon

- Jubilees at earlyjewishwritings.com

- Ge'ez text of Jubilees (first page)

- Ethiopic Jubilees Reading Guide: 11:1-10

- Ethiopic Jubilees Reading Guide: 17:15-18:16