Tower of Babel

The Tower of Babel (Hebrew: מִגְדַּל בָּבֶל, Migdal Bavel) narrative in Genesis 11:1–9 is an origin myth meant to explain why the world's peoples speak different languages.[1][2][3][4]

| Tower of Babel | |

|---|---|

מִגְדַּל בָּבֶל | |

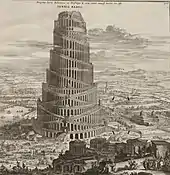

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) The Tower of Babel by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1563) | |

| General information | |

| Type | Tower |

| Location | Babylon |

| Height | See § Height |

According to the story, a united human race in the generations following the Great Flood, speaking a single language and migrating eastward, comes to the land of Shinar (שִׁנְעָר). There they agree to build a city and a tower tall enough to reach heaven. God, observing their city and tower, confounds their speech so that they can no longer understand each other, and scatters them around the world.

Some modern scholars have associated the Tower of Babel with known structures, notably the Etemenanki, a ziggurat dedicated to the Mesopotamian god Marduk in Babylon. A Sumerian story with some similar elements is told in Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta.[5]

Biblical narrative

1 And the whole earth was of one language, and of one speech.

2 And it came to pass, as they journeyed from the east, that they found a plain in the land of Shinar; and they dwelt there.

3 And they said one to another, Go to, let us make brick, and burn them throughly. And they had brick for stone, and slime had they for morter.

4 And they said, Go to, let us build us a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.

5 And the LORD came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of men builded.

6 And the LORD said, Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language; and this they begin to do: and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do.

7 Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another's speech.

8 So the LORD scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of all the earth: and they left off to build the city.9 Therefore is the name of it called Babel; because the LORD did there confound the language of all the earth: and from thence did the LORD scatter them abroad upon the face of all the earth.

— Genesis 11:1–9[6]

Etymology

The phrase "Tower of Babel" does not appear in the Bible; it is always "the city and the tower" (אֶת-הָעִיר וְאֶת-הַמִּגְדָּל) or just "the city" (הָעִיר). The original derivation of the name Babel (also the Hebrew name for Babylon) is uncertain. The native, Akkadian name of the city was Bāb-ilim, meaning "gate of God". However, that form and interpretation itself are now usually thought to be the result of an Akkadian folk etymology applied to an earlier form of the name, Babilla, of unknown meaning and probably non-Semitic origin.[7][8] According to the Bible, the city received the name "Babel" from the Hebrew verb בָּלַ֥ל (bālal), meaning to jumble or to confuse.[9]

Composition

Genre

The narrative of the tower of Babel Genesis 11:1–9 is an etiology or explanation of a phenomenon. Etiologies are narratives that explain the origin of a custom, ritual, geographical feature, name, or other phenomenon.[10]:426 The story of the Tower of Babel explains the origins of the multiplicity of languages. God was concerned that humans had blasphemed by building the tower to avoid a second flood so God brought into existence multiple languages.[10]:51 Thus, humans were divided into linguistic groups, unable to understand one another.

Themes

The story's theme of competition between God and humans appears elsewhere in Genesis, in the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden.[11] The 1st-century Jewish interpretation found in Flavius Josephus explains the construction of the tower as a hubristic act of defiance against God ordered by the arrogant tyrant Nimrod. There have, however, been some contemporary challenges to this classical interpretation, with emphasis placed on the explicit motive of cultural and linguistic homogeneity mentioned in the narrative (v. 1, 4, 6).[12] This reading of the text sees God's actions not as a punishment for pride, but as an etiology of cultural differences, presenting Babel as the cradle of civilization.

Authorship and source criticism

Jewish and Christian tradition attributes the composition of the whole Pentateuch, which includes the story of the Tower of Babel, to Moses. Modern Biblical scholarship rejects Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch, but is divided on the question of its authorship. Many scholars subscribe to some form of the documentary hypothesis, which argues that the Pentateuch is composed of multiple "sources" that were later merged together. Scholars who favor this hypothesis, such as Richard Elliot Friedman, tend to see the Genesis 11:1-9 as being composed by the J or Jahwist/Yahwist source.[13] Michael Coogan suggests the intentional word play regarding the city of Babel, and the noise of the people's "babbling" is found in the Hebrew words as easily as in English, is considered typical of the Yahwist source.[10]:51 John Van Seters, who has put forth substantial modifications to the hypothesis, suggests that these verses are part of what he calls a "Pre-Yahwistic stage".[14] Other scholars reject the documentary hypothesis all together. The "minimalist" scholars tend to see the books of Genesis through 2 Kings as written by a single, anonymous author during the Hellenistic period. Philippe Wajdenbaum suggests that the Tower of Babel story is evidence that this author was familiar with the works of both Herodotus and Plato.[15]

Comparable myths

Sumerian and Assyrian parallel

There is a Sumerian myth similar to that of the Tower of Babel, called Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta,[5] where Enmerkar of Uruk is building a massive ziggurat in Eridu and demands a tribute of precious materials from Aratta for its construction, at one point reciting an incantation imploring the god Enki to restore (or in Kramer's translation, to disrupt) the linguistic unity of the inhabited regions—named as Shubur, Hamazi, Sumer, Uri-ki (Akkad), and the Martu land, "the whole universe, the well-guarded people—may they all address Enlil together in a single language."[16]

In addition, a further Assyrian myth, dating from the 8th century BC during the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BC) bears a number of similarities to the later written Biblical story.[17]

Greco-Roman parallel

In Greek mythology, much of which was adopted by the Romans, there is a myth referred to as the Gigantomachy, the battle fought between the Giants and the Olympian gods for supremacy of the cosmos. In Ovid's telling of the myth, the Giants attempt to reach the gods in heaven by stacking mountains, but are repelled by Jupiter's thunderbolts. A.S. Kline translates Metamorphoses 1.151-155 as:

"Rendering the heights of heaven no safer than the earth, they say the giants attempted to take the Celestial kingdom, piling mountains up to the distant stars. Then the all-powerful father of the gods hurled his bolt of lightning, fractured Olympus and threw Mount Pelion down from Ossa below."[18]

Biblical scholar Philippe Wajdenbaum suggests that the author of Genesis was familiar with the Gigantomachy myth and used it to compose the Tower of Babel story.[15]

Mexico

Various traditions similar to that of the tower of Babel are found in Central America. Some writers connected the Great Pyramid of Cholula to the Tower of Babel. The Dominican friar Diego Durán (1537–1588) reported hearing an account about the pyramid from a hundred-year-old priest at Cholula, shortly after the conquest of Mexico. He wrote that he was told when the light of the sun first appeared upon the land, giants appeared and set off in search of the sun. Not finding it, they built a tower to reach the sky. An angered God of the Heavens called upon the inhabitants of the sky, who destroyed the tower and scattered its inhabitants. The story was not related to either a flood or the confusion of languages, although Frazer connects its construction and the scattering of the giants with the Tower of Babel.[19]

Another story, attributed by the native historian Fernando de Alva Cortés Ixtlilxóchitl (c. 1565–1648) to the ancient Toltecs, states that after men had multiplied following a great deluge, they erected a tall zacuali or tower, to preserve themselves in the event of a second deluge. However, their languages were confounded and they went to separate parts of the earth.[20]

Arizona

Still another story, attributed to the Tohono O'odham people, holds that Montezuma escaped a great flood, then became wicked and attempted to build a house reaching to heaven, but the Great Spirit destroyed it with thunderbolts.[21][22]

Cherokee

One version of the Cherokee origin story recounted in 1896 has both a tower narrative and a flood narrative: "When we lived beyond the great waters there were twelve clans belonging to the Cherokee tribe. And back in the old country in which we lived the country was subject to great floods. So in the course of time we held a council and decided to build a storehouse reaching to heaven. The Cherokees said that when the house was build and the floods came the tribe would just leave the earth and go to heaven. And we commenced to build a great structure, and when it was towering into one of the highest heavens the great powers destroyed the apex, cutting it down to about half of its height. But as the tribe was fully determined to build to heaven for safety they were not discouraged but commenced to repair the damage done by the gods. Finally they completed the lofty structure and considered themselves safe from the floods. But after it was completed the gods destroyed the high part, again, and when they determined to repair the damage they found that the language of the tribe was confused or destroyed."[23]

Nepal

Traces of a somewhat similar story have also been reported among the Tharu of Nepal and northern India.[24]

Botswana

According to David Livingstone, the people he met living near Lake Ngami in 1849 had such a tradition, but with the builders' heads getting "cracked by the fall of the scaffolding".[25]

Other traditions

In his 1918 book, Folklore in the Old Testament, Scottish social anthropologist Sir James George Frazer documented similarities between Old Testament stories, such as the Flood, and indigenous legends around the world. He identified Livingston's account with a tale found in Lozi mythology, wherein the wicked men build a tower of masts to pursue the Creator-God, Nyambe, who has fled to Heaven on a spider-web, but the men perish when the masts collapse. He further relates similar tales of the Ashanti that substitute a pile of porridge pestles for the masts. Frazer moreover cites such legends found among the Kongo people, as well as in Tanzania, where the men stack poles or trees in a failed attempt to reach the moon.[19] He further cited the Karbi and Kuki people of Assam as having a similar story. The traditions of the Karen people of Myanmar, which Frazer considered to show clear 'Abrahamic' influence, also relate that their ancestors migrated there following the abandonment of a great pagoda in the land of the Karenni 30 generations from Adam, when the languages were confused and the Karen separated from the Karenni. He notes yet another version current in the Admiralty Islands, where mankind's languages are confused following a failed attempt to build houses reaching to heaven.

Historical context

Biblical scholars see the Book of Genesis as mythological and not as a historical account of events.[26] Nonetheless, the story of Babel can be interpreted in terms of its context.

Genesis 10:10 states that Babel (LXX: Βαβυλών) formed part of Nimrod's kingdom. The Bible does not specifically mention that Nimrod ordered the building of the tower, but many other sources have associated its construction with Nimrod.[27]

Genesis 11:9 attributes the Hebrew version of the name, Babel, to the verb balal, which means to confuse or confound in Hebrew. The first century Roman-Jewish author Flavius Josephus similarly explained that the name was derived from the Hebrew word Babel (בבל), meaning "confusion".[28]

Destruction

The account in Genesis makes no mention of any destruction of the tower. The people whose languages are confounded were simply scattered from there over the face of the Earth and stopped building their city. However, in other sources, such as the Book of Jubilees (chapter 10 v.18–27), Cornelius Alexander (frag. 10), Abydenus (frags. 5 and 6), Josephus (Antiquities 1.4.3), and the Sibylline Oracles (iii. 117–129), God overturns the tower with a great wind. In the Talmud, it said that the top of the tower was burnt, the bottom was swallowed, and the middle was left standing to erode over time (Sanhedrin 109a).

Etemenanki, the ziggurat at Babylon

Etemenanki (Sumerian: "temple of the foundation of heaven and earth") was the name of a ziggurat dedicated to Marduk in the city of Babylon. It was famously rebuilt by the 6th-century BCE Neo-Babylonian dynasty rulers Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar II, but had fallen into disrepair by the time of Alexander's conquests. He managed to move the tiles of the tower to another location, but his death stopped the reconstruction, and it was demolished during the reign of his successor Antiochus Soter. The Greek historian Herodotus (c. 484 – c. 425 BC) wrote an account of the ziggurat in his Histories, which he called the "Temple of Zeus Belus".[29]

According to modern scholars, the biblical story of the Tower of Babel was likely influenced by Etemenanki. Stephen L. Harris proposed this occurred during the Babylonian captivity.[30] Isaac Asimov speculated that the authors of Genesis 11:1–9 were inspired by the existence of an apparently incomplete ziggurat at Babylon, and by the phonological similarity between Babylonian Bab-ilu, meaning "gate of God", and the Hebrew word balal, meaning "mixed", "confused", or "confounded".[31] Philippe Wajdenbaum suggests Genesis 11:3 was directly referencing Herodotus' description of the construction processes used in Babylon and Etemenanki in Histories book I 179 & 181, and was therefore written in the Hellenistic period.[15]

In other sources

Book of Jubilees

The Book of Jubilees contains one of the most detailed accounts found anywhere of the Tower.

And they began to build, and in the fourth week they made brick with fire, and the bricks served them for stone, and the clay with which they cemented them together was asphalt which comes out of the sea, and out of the fountains of water in the land of Shinar. And they built it: forty and three years were they building it; its breadth was 203 bricks, and the height [of a brick] was the third of one; its height amounted to 5433 cubits and 2 palms, and [the extent of one wall was] thirteen stades [and of the other thirty stades]. (Jubilees 10:20–21, Charles' 1913 translation)

Pseudo-Philo

In Pseudo-Philo, the direction for the building is ascribed not only to Nimrod, who is made prince of the Hamites, but also to Joktan, as prince of the Semites, and to Phenech son of Dodanim, as prince of the Japhetites. Twelve men are arrested for refusing to bring bricks, including Abraham, Lot, Nahor, and several sons of Joktan. However, Joktan finally saves the twelve from the wrath of the other two princes.[32]

Josephus' Antiquities of the Jews

The Jewish-Roman historian Flavius Josephus, in his Antiquities of the Jews (c. 94 CE), recounted history as found in the Hebrew Bible and mentioned the Tower of Babel. He wrote that it was Nimrod who had the tower built and that Nimrod was a tyrant who tried to turn the people away from God. In this account, God confused the people rather than destroying them because annihilation with a Flood had not taught them to be godly.

Now it was Nimrod who excited them to such an affront and contempt of God. He was the grandson of Ham, the son of Noah, a bold man, and of great strength of hand. He persuaded them not to ascribe it to God as if it were through his means they were happy, but to believe that it was their own courage which procured that happiness. He also gradually changed the government into tyranny, seeing no other way of turning men from the fear of God, but to bring them into a constant dependence on his power... Now the multitude were very ready to follow the determination of Nimrod and to esteem it a piece of cowardice to submit to God; and they built a tower, neither sparing any pains, nor being in any degree negligent about the work: and, by reason of the multitude of hands employed in it, it grew very high, sooner than any one could expect; but the thickness of it was so great, and it was so strongly built, that thereby its great height seemed, upon the view, to be less than it really was. It was built of burnt brick, cemented together with mortar, made of bitumen, that it might not be liable to admit water. When God saw that they acted so madly, he did not resolve to destroy them utterly, since they were not grown wiser by the destruction of the former sinners [in the Flood]; but he caused a tumult among them, by producing in them diverse languages, and causing that, through the multitude of those languages, they should not be able to understand one another. The place wherein they built the tower is now called Babylon, because of the confusion of that language which they readily understood before; for the Hebrews mean by the word Babel, confusion. The Sibyl also makes mention of this tower, and of the confusion of the language, when she says thus:—"When all men were of one language, some of them built a high tower, as if they would thereby ascend up to heaven; but the gods sent storms of wind and overthrew the tower, and gave everyone a peculiar language; and for this reason it was that the city was called Babylon."

Greek Apocalypse of Baruch

Third Apocalypse of Baruch (or 3 Baruch, c. 2nd century), one of the pseudepigrapha, describes the just rewards of sinners and the righteous in the afterlife.[11] Among the sinners are those who instigated the Tower of Babel. In the account, Baruch is first taken (in a vision) to see the resting place of the souls of "those who built the tower of strife against God, and the Lord banished them." Next he is shown another place, and there, occupying the form of dogs,

Those who gave counsel to build the tower, for they whom thou seest drove forth multitudes of both men and women, to make bricks; among whom, a woman making bricks was not allowed to be released in the hour of child-birth, but brought forth while she was making bricks, and carried her child in her apron, and continued to make bricks. And the Lord appeared to them and confused their speech, when they had built the tower to the height of four hundred and sixty-three cubits. And they took a gimlet, and sought to pierce the heavens, saying, Let us see (whether) the heaven is made of clay, or of brass, or of iron. When God saw this He did not permit them, but smote them with blindness and confusion of speech, and rendered them as thou seest. (Greek Apocalypse of Baruch, 3:5–8)

Midrash

Rabbinic literature offers many different accounts of other causes for building the Tower of Babel, and of the intentions of its builders. According to one midrash the builders of the Tower, called "the generation of secession" in the Jewish sources, said: "God has no right to choose the upper world for Himself, and to leave the lower world to us; therefore we will build us a tower, with an idol on the top holding a sword, so that it may appear as if it intended to war with God" (Gen. R. xxxviii. 7; Tan., ed. Buber, Noah, xxvii. et seq.).

The building of the Tower was meant to bid defiance not only to God, but also to Abraham, who exhorted the builders to reverence. The passage mentions that the builders spoke sharp words against God, saying that once every 1,656 years, heaven tottered so that the water poured down upon the earth, therefore they would support it by columns that there might not be another deluge (Gen. R. l.c.; Tan. l.c.; similarly Josephus, "Ant." i. 4, § 2).

Some among that generation even wanted to war against God in heaven (Talmud Sanhedrin 109a). They were encouraged in this undertaking by the notion that arrows that they shot into the sky fell back dripping with blood, so that the people really believed that they could wage war against the inhabitants of the heavens (Sefer ha-Yashar, Chapter 9:12–36). According to Josephus and Midrash Pirke R. El. xxiv., it was mainly Nimrod who persuaded his contemporaries to build the Tower, while other rabbinical sources assert, on the contrary, that Nimrod separated from the builders.[27]

According to another midrashic account, one third of the Tower builders were punished by being transformed into semi-demonic creatures and banished into three parallel dimensions, inhabited now by their descendants.[33]

Islamic tradition

Although not mentioned by name, the Quran has a story with similarities to the biblical story of the Tower of Babel, although set in the Egypt of Moses: Pharaoh asks Haman to build him a stone (or clay) tower so that he can mount up to heaven and confront the God of Moses.[34]

Another story in Sura 2:102 mentions the name of Babil, but tells of when the two angels Harut and Marut taught magic to some people in Babylon and warned them that magic is a sin and that their teaching them magic is a test of faith.[35] A tale about Babil appears more fully in the writings of Yaqut (i, 448 f.) and the Lisān al-ʿArab (xiii. 72), but without the tower: mankind were swept together by winds into the plain that was afterward called "Babil", where they were assigned their separate languages by God, and were then scattered again in the same way. In the History of the Prophets and Kings by the 9th-century Muslim theologian al-Tabari, a fuller version is given: Nimrod has the tower built in Babil, God destroys it, and the language of mankind, formerly Syriac, is then confused into 72 languages. Another Muslim historian of the 13th century, Abu al-Fida relates the same story, adding that the patriarch Eber (an ancestor of Abraham) was allowed to keep the original tongue, Hebrew in this case, because he would not partake in the building.[27]

Although variations similar to the biblical narrative of the Tower of Babel exist within Islamic tradition, the central theme of God separating humankind on the basis of language is alien to Islam according to the author Yahiya Emerick. In Islamic belief, he argues, God created nations to know each other and not to be separated.[36]

Book of Mormon

In the Book of Mormon, a man named Jared and his family ask God that their language not be confounded at the time of the "great tower". Because of their prayers, God preserves their language and leads them to the Valley of Nimrod. From there, they travel across the sea to the Americas.[37]

Despite no mention of the Tower of Babel in the original text of the Book of Mormon, some leaders in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints assert that the "great tower" was indeed the Tower of Babel - as in the 1981 introduction to the Book of Mormon - despite the chronology of the Book of Ether aligning more closely with the 21st century BC Sumerian tower temple myth of Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta to the goddess Innana.[38] Church apologists have also supported this connection and argue the reality of the Tower of Babel: "Although there are many in our day who consider the accounts of the Flood and tower of Babel to be fiction, Latter-day Saints affirm their reality."[39] In either case, the church firmly believes in the factual nature of at least one "great tower" built in the region of ancient Sumeria/Assyria/Babylonia.

Confusion of tongues

The confusion of tongues (confusio linguarum) is the origin myth for the fragmentation of human languages described in Genesis 11:1–9, as a result of the construction of the Tower of Babel. Prior to this event, humanity was stated to speak a single language. The preceding Genesis 10:5 states that the descendants of Japheth, Gomer, and Javan dispersed "with their own tongues," creating an apparent contradiction. Scholars have been debating or explaining this apparent contradiction for centuries.[40]

During the Middle Ages, the Hebrew language was widely considered the language used by God to address Adam in Paradise, and by Adam as lawgiver (the Adamic language) by various Jewish, Christian, and Muslim scholastics.

Dante Alighieri addresses the topic in his De vulgari eloquentia (1302-1305). He argues that the Adamic language is of divine origin and therefore unchangeable.[41] He also notes that according to Genesis, the first speech act is due to Eve, addressing the serpent, and not to Adam.[42]

In his Divine Comedy (c. 1308-1320), however, Dante changes his view to another that treats the Adamic language as the product of Adam.[41] This had the consequence that it could no longer be regarded as immutable, and hence Hebrew could not be regarded as identical with the language of Paradise. Dante concludes (Paradiso XXVI) that Hebrew is a derivative of the language of Adam. In particular, the chief Hebrew name for God in scholastic tradition, El, must be derived of a different Adamic name for God, which Dante gives as I.[41]

Before the acceptance of the Indo-European language family, these languages were considered to be "Japhetite" by some authors (e.g., Rasmus Rask in 1815; see Indo-European studies). Beginning in Renaissance Europe, priority over Hebrew was claimed for the alleged Japhetic languages, which were supposedly never corrupted because their speakers had not participated in the construction of the Tower of Babel. Among the candidates for a living descendant of the Adamic language were: Gaelic (see Auraicept na n-Éces); Tuscan (Giovanni Battista Gelli, 1542, Piero Francesco Giambullari, 1564); Dutch (Goropius Becanus, 1569, Abraham Mylius, 1612); Swedish (Olaus Rudbeck, 1675); German (Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, 1641, Schottel, 1641). The Swedish physician Andreas Kempe wrote a satirical tract in 1688, where he made fun of the contest between the European nationalists to claim their native tongue as the Adamic language. Caricaturing the attempts by the Swede Olaus Rudbeck to pronounce Swedish the original language of mankind, Kempe wrote a scathing parody where Adam spoke Danish, God spoke Swedish, and the serpent French.[43]

The primacy of Hebrew was still defended by some authors until the emergence of modern linguistics in the second half of the 18th century, e.g. by Pierre Besnier (1648–1705) in A philosophicall essay for the reunion of the languages, or, the art of knowing all by the mastery of one (1675) and by Gottfried Hensel (1687–1767) in his Synopsis Universae Philologiae (1741).

Linguistics

For a long time, Historical linguistics wrestled with the idea of a single original language. In the Middle Ages, and down to the 17th century, attempts were made to identify a living descendant of the Adamic language.

Multiplication of languages

.jpg.webp)

The literal belief that the world's linguistic variety originated with the tower of Babel is pseudolinguistics, and is contrary to the known facts about the origin and history of languages.[44]

In the Biblical introduction of the Tower of Babel account, in Genesis 11:1, it is said that everyone on Earth spoke the same language, but this is inconsistent with the Biblical description of the post-Noahic world described in Genesis 10:5, where it is said that the descendants of Shem, Ham, and Japheth gave rise to different nations, each with their own language.[2]:26

There have also been a number of traditions around the world that describe a divine confusion of the one original language into several, albeit without any tower. Aside from the Ancient Greek myth that Hermes confused the languages, causing Zeus to give his throne to Phoroneus, Frazer specifically mentions such accounts among the Wasania of Kenya, the Kacha Naga people of Assam, the inhabitants of Encounter Bay in Australia, the Maidu of California, the Tlingit of Alaska, and the K'iche' Maya of Guatemala.[45]

The Estonian myth of "the Cooking of Languages"[46] has also been compared.

Enumeration of scattered languages

There are several mediaeval historiographic accounts that attempt to make an enumeration of the languages scattered at the Tower of Babel. Because a count of all the descendants of Noah listed by name in chapter 10 of Genesis (LXX) provides 15 names for Japheth's descendants, 30 for Ham's, and 27 for Shem's, these figures became established as the 72 languages resulting from the confusion at Babel—although the exact listing of these languages changed over time. (The LXX Bible has two additional names, Elisa and Cainan, not found in the Masoretic text of this chapter, so early rabbinic traditions, such as the Mishna, speak instead of "70 languages".) Some of the earliest sources for 72 (sometimes 73) languages are the 2nd-century Christian writers Clement of Alexandria (Stromata I, 21) and Hippolytus of Rome (On the Psalms 9); it is repeated in the Syriac book Cave of Treasures (c. 350 CE), Epiphanius of Salamis' Panarion (c. 375) and St. Augustine's The City of God 16.6 (c. 410). The chronicles attributed to Hippolytus (c. 234) contain one of the first attempts to list each of the 72 peoples who were believed to have spoken these languages.

Isidore of Seville in his Etymologiae (c. 600) mentions the number of 72; however, his list of names from the Bible drops the sons of Joktan and substitutes the sons of Abraham and Lot, resulting in only about 56 names total; he then appends a list of some of the nations known in his own day, such as the Longobards and the Franks. This listing was to prove quite influential on later accounts that made the Lombards and Franks themselves into descendants of eponymous grandsons of Japheth, e.g. the Historia Brittonum (c. 833), The Meadows of Gold by al Masudi (c. 947) and Book of Roads and Kingdoms by al-Bakri (1068), the 11th-century Lebor Gabála Érenn, and the midrashic compilations Yosippon (c. 950), Chronicles of Jerahmeel, and Sefer haYashar.

Other sources that mention 72 (or 70) languages scattered from Babel are the Old Irish poem Cu cen mathair by Luccreth moccu Chiara (c. 600); the Irish monastic work Auraicept na n-Éces; History of the Prophets and Kings by the Persian historian Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari (c. 915); the Anglo-Saxon dialogue Solomon and Saturn; the Russian Primary Chronicle (c. 1113); the Jewish Kabbalistic work Bahir (1174); the Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson (c. 1200); the Syriac Book of the Bee (c. 1221); the Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum (c. 1284; mentions 22 for Shem, 31 for Ham and 17 for Japheth for a total of 70); Villani's 1300 account; and the rabbinic Midrash ha-Gadol (14th century). Villani adds that it "was begun 700 years after the Flood, and there were 2,354 years from the beginning of the world to the confusion of the Tower of Babel. And we find that they were 107 years working at it; and men lived long in those times". According to the Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum, however, the project was begun only 200 years following the Deluge.

The tradition of 72 languages persisted into later times. Both José de Acosta in his 1576 treatise De procuranda indorum salute, and António Vieira a century later in his Sermão da Epifania, expressed amazement at how much this 'number of tongues' could be surpassed, there being hundreds of mutually unintelligible languages indigenous only to Peru and Brazil.

Height

The Book of Genesis does not mention how tall the tower was. The phrase used to describe the tower, "its top in the sky" (v.4), was an idiom for impressive height; rather than implying arrogance, this was simply a cliché for height.[12]:37

The Book of Jubilees mentions the tower's height as being 5,433 cubits and 2 palms, or 2,484 m (8,150 ft), about three times the height of Burj Khalifa, or roughly 1.6 miles high. The Third Apocalypse of Baruch mentions that the 'tower of strife' reached a height of 463 cubits, or 211.8 m (695 ft), taller than any structure built in human history until the construction of the Eiffel Tower in 1889, which is 324 m (1,063 ft) in height.

Gregory of Tours writing c. 594, quotes the earlier historian Orosius (c. 417) as saying the tower was "laid out foursquare on a very level plain. Its wall, made of baked brick cemented with pitch, is fifty cubits wide, two hundred high, and four hundred and seventy stades in circumference. A stade was an ancient Greek unit of length, based on the circumference of a typical sports stadium of the time which was about 176 metres (577 ft).[47] Twenty-five gates are situated on each side, which make in all one hundred. The doors of these gates, which are of wonderful size, are cast in bronze. The same historian tells many other tales of this city, and says: 'Although such was the glory of its building still it was conquered and destroyed.'"[48]

A typical medieval account is given by Giovanni Villani (1300): He relates that "it measured eighty miles [130 km] round, and it was already 4,000 paces high, or 5.92 km (3.68 mi) and 1,000 paces thick, and each pace is three of our feet."[49] The 14th-century traveler John Mandeville also included an account of the tower and reported that its height had been 64 furlongs, or 13 km (8 mi), according to the local inhabitants.

The 17th-century historian Verstegan provides yet another figure – quoting Isidore, he says that the tower was 5,164 paces high, or 7.6 km (4.7 mi), and quoting Josephus that the tower was wider than it was high, more like a mountain than a tower. He also quotes unnamed authors who say that the spiral path was so wide that it contained lodgings for workers and animals, and other authors who claim that the path was wide enough to have fields for growing grain for the animals used in the construction.

In his book, Structures: Or Why Things Don't Fall Down (Pelican 1978–1984), Professor J.E. Gordon considers the height of the Tower of Babel. He wrote, "brick and stone weigh about 120 lb per cubic foot (2,000 kg per cubic metre) and the crushing strength of these materials is generally rather better than 6,000 lbs per square inch or 40 mega-pascals. Elementary arithmetic shows that a tower with parallel walls could have been built to a height of 2.1 km (1.3 mi) before the bricks at the bottom were crushed. However, by making the walls taper towards the top they ... could well have been built to a height where the men of Shinnar would run short of oxygen and had difficulty in breathing before the brick walls crushed beneath their own dead weight."

In popular culture

Pieter Brueghel's influential portrayal is based on the Colosseum in Rome, while later conical depictions of the tower (as depicted in Doré's illustration) resemble much later Muslim towers observed by 19th-century explorers in the area, notably the Minaret of Samarra. M.C. Escher depicts a more stylized geometrical structure in his woodcut representing the story.

The composer Anton Rubinstein wrote an opera based on the story Der Thurm zu Babel.

American choreographer Adam Darius staged a multilingual theatrical interpretation of The Tower of Babel in 1993 at the ICA in London.

Fritz Lang's 1927 film Metropolis, in a flashback, plays upon themes of lack of communication between the designers of the tower and the workers who are constructing it. The short scene states how the words used to glorify the tower's construction by its designers took on totally different, oppressive meanings to the workers. This led to its destruction as they rose up against the designers because of the insufferable working conditions. The appearance of the tower was modeled after Brueghel's 1563 painting.[50]

The political philosopher Michael Oakeshott surveyed historic variations of the Tower of Babel in different cultures[51] and produced a modern retelling of his own in his 1983 book, On History.[52] In his retelling, Oakeshott expresses disdain for human willingness to sacrifice individuality, culture, and quality of life for grand collective projects. He attributes this behavior to fascination with novelty, persistent dissatisfaction, greed, and lack of self-reflection.[53]

A.S. Byatt's novel Babel Tower (1996) is about the question "whether language can be shared, or, if that turns out to be illusory, how individuals, in talking to each other, fail to understand each other".[54]

The progressive band Soul Secret wrote a concept album called BABEL, based on a modernized version of the myth.

Science fiction writer Ted Chiang wrote a story called "Tower of Babylon" that imagined a miner's climbing the tower all the way to the top where he meets the vault of heaven.[55]

Fantasy novelist Josiah Bancroft has a series The Books of Babel, which is to conclude with book IV in 2021.

This biblical episode is dramatized in the Indian television series Bible Ki Kahaniyan, which aired on DD National from 1992.[56]

In the 1990 Japanese television anime Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water, the Tower of Babel is used by the Atlanteans as an interstellar communication device.[57] Later in the series, the Neo Atlanteans rebuild the Tower of Babel and use its communication beam as a weapon of mass destruction. Both the original and the rebuilt tower resembles the painting Tower of Babel by artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

In the game called Prince of Persia: The Two Thrones the last stages of the game and the final boss fight occurs in the tower.

In the web-based game Forge of Empires the Tower of Babel is an available "Great Building".

Argentinian novelist Jorge Luis Borges wrote a story called "The Library of Babel".

The Tower of Babel appears as an important location in the Babylonian story arc of the Japanese shōjo manga Crest of the Royal Family.

See also

References

- Metzger, Bruce Manning; Coogan, Michael D (2004). The Oxford Guide To People And Places of the Bible. Oxford University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-19-517610-0. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- Levenson, Jon D. (2004). "Genesis: Introduction and Annotations". In Berlin, Adele; Brettler, Marc Zvi (eds.). The Jewish Study Bible. Oxford University Press. p. 29. ISBN 9780195297515.

The Jewish study Bible.

- Graves, Robert; Patai, Raphael (1986). Hebrew Myths: The Book of Genesis. Random House. p. 315. ISBN 9780795337154.

- Schwartz, Howard; Loebel-Fried, Caren; Ginsburg, Elliot K. (2007). Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism. Oxford University Press. p. 704. ISBN 9780195358704.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1968). "The 'Babel of Tongues': A Sumerian Version". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 88 (1). pp. 108–111.

- Genesis 11:1–9 KJV

- Day, John (2014). From Creation to Babel: Studies in Genesis 1-11. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 179–180. ISBN 978-0-567-37030-3.

- Dietz Otto Edzard: Geschichte Mesopotamiens. Von den Sumerern bis zu Alexander dem Großen, Beck, München 2004, p. 121.

- John L. Mckenzie (1995). The Dictionary of the Bible. Simon and Schuster. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-684-81913-6.

- Coogan, Michael D. (2009). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament: the Hebrew Bible in its Context. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195332728.

- Harris, Stephen L. (1985). Understanding the Bible: A Reader's Introduction. Palo Alto: Mayfield. ISBN 9780874846966.

- Hiebert, Theodore (2007). "The Tower of Babel and the Origin of the World's Cultures". Journal of Biblical Literature. 126 (1): 29–58. doi:10.2307/27638419. JSTOR 27638419.

- Friedman, Richard Elliot (1997). Who Wrote the Bible?. Simon & Schuster. p. 247. ISBN 0-06-063035-3.

- Van Seters, John (1975). Abraham in History and Tradition. Echo Point Books & Media. p. 313. ISBN 978-1-62654-006-4.

- Wajdenbaum, Philippe (2014). Argonauts of the Desert: Structural Analysis of the Hebrew Bible (Copenhagen International Seminar). Routledge. pp. 110–112. ISBN 978-1845539245.

- "Enmerkar and the lord of Aratta: composite text." Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Line 145f.: an-ki ningin2-na ung3 sang sig10-ga den-lil2-ra eme 1-am3 he2-en-na-da-ab-dug4.

- Petros Koutoupis, "Gateway to the Heavens: The Assyrian Account to the Tower of Babel". Ancient Origins. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- https://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Metamorph.htm#488381096. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Frazer, James George (1919). Folk-lore in the Old Testament: Studies in Comparative Religion, Legend and Law. London: Macmillan. pp. 362–387.

- "Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxóchitl". letras-uruguay.espaciolatino.com. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- Bancroft, vol. 3, p. 76.

- Farish, Thomas Edwin (1918). History of Arizona, Volume VII. Phoenix. pp. 309–310. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- Sanders, George Sahkiyah (2017). Yates, Donald N (ed.). The Cherokee Origin Narrative. Translated by Eubanks, William (4th ed.). Longmont, CO: Panther`s Lodge Publishers. pp. 1–3. ISBN 9781974441617. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Beverley, H. (1872). Report on the Census of Bengal. Calcutta: Bengal Secretariat Press. p. 160.

- David Livingstone (1858). Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa. Harper & Brothers. p. 567.

- Levenson 2004, p. 11 "How much history lies behind the story of Genesis? Because the action of the primeval story is not represented as taking place on the plane of ordinary human history and has so many affinities with ancient mythology, it is very far-fetched to speak of its narratives as historical at all."

- Jastrow, Morris; Price, Ira Maurice; Jastrow, Marcus; Ginzberg, Louis; MacDonald, Duncan B. (1906). "Babel, Tower of". Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. pp. 395–398.

- Josephus, Antiquities, 1.4.3

- http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0126%3Abook%3D1%3Achapter%3D179. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Harris, Stephen L. (2002). Understanding the Bible. McGraw-Hill. pp. 50–51. ISBN 9780767429160.

- Asimov, Isaac (1971). Asimov's Guide to the Bible, vol.1: The Old Testament. Avon Books. pp. 54–55. ISBN 9780380010325.

- The Biblical Antiquities of Philo. Translated by James, M. R. London: SPCK. 1917. pp. 90–94.

- Ginzberg, Louis (1909). Legends of the Jews, Volume 1. New York. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015.

- Pickthal, M. "Quran" (in English), Suras 28:36 and 40:36–37. Amana Publishers, UK 1996

- "Surat Al-Baqarah [2:102] – The Noble Qur'an – القرآن الكريم". Quran.com. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- Emerick, Yahiya (2002). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Understanding Islam. Indianapolis: Alpha. p. 108. ISBN 9780028642338.

- Ether 1:33–38

- Daniel H. Ludlow, A Companion to Your Study of the Book of Mormon p. 117, quoted in Church Educational System (1996, rev. ed.). Book of Mormon Student Manual (Salt Lake City, Utah: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints), ch. 6.

- Parry, Donald W. (January 1998), "The Flood and the Tower of Babel", Ensign

- Louth, Andrew; Oden, Thomas C.; Conti, Marco (2001). Genesis 1-11; Volume 1. Taylor & Francis. p. 164. ISBN 1579582206.

- Mazzocco, Angelo (1993). Linguistic Theories in Dante and the Humanists. pp. 159–181. ISBN 978-90-04-09702-5.

- mulierem invenitur ante omnes fuisse locutam. Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language (1993), p. 50.

- Olender, Maurice (1992). The Languages of Paradise: Race, Religion, and Philology in the Nineteenth Century. Trans. Arthur Goldhammer. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-51052-6.

- Pennock, Robert T. (2000). Tower of Babel: The Evidence against the New Creationism. Bradford Books. ISBN 9780262661652.

- Frazer, James George (1919). Folk-lore in the Old Testament: Studies in Comparative Religion, Legend and Law. London: Macmillan. p. 384.

- Kohl, Reisen in die 'Ostseeprovinzen, ii. 251–255

- Donald Engels (1985). The Length of Eratosthenes' Stade. American Journal of Philology 106 (3): 298–311. doi:10.2307/295030 (subscription required).

- Gregory of Tours, History of the Franks, from the 1916 translation by Earnest Brehaut, Book I, chapter 6. Available online in abridged form.

- Selections from Giovanni's Chronicle in English.

- Bukatman, Scott (1997). Blade Runner. London: British Film Institute. pp. 62–63. ISBN 0-85170-623-1.

- Worthington, G. (2016). Religious and Poetic Experience in the Thought of Michael Oakeshott. British Idealist Studies 1: Oakeshott. Andrews UK Limited. p. 121f. ISBN 978-1-84540-594-6.

- Reprinted as Oakeshott, Michael (1989). "The tower of Babel". In Clarke, S.G.; Simpson, E. (eds.). Anti-Theory in Ethics and Moral Conservatism. SUNY Series in Ethical Theory. State University of New York Press. p. 185ff. ISBN 978-0-88706-912-3. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- Corey, E. C. (2006). Michael Oakeshott on Religion, Aesthetics, and Politics. Eric Voegelin Institute series in political philosophy. University of Missouri Press. pp. 129–131. ISBN 978-0-8262-6517-3.

- Dorschel, Andreas (25 November 2004). "Ach, Sie waren nicht in Oxford? Antonia S. Byatts Roman "Der Turm zu Babel"". Süddeutsche Zeitung 274 (in German). p. 16.

- Joshua Rothman, "Ted Chiang's Soulful Science Fiction", The New Yorker, 2017

- Menon, Ramesh (15 November 1989). "Bible ki Kahaniyan: Another religious saga on the small screen". India Today.

- "NADIA & REALITY". Tamaro Forever presents The Secret of Blue Water. 13 June 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

Further reading

- Sayce, Archibald Henry (1878), , in Baynes, T. S. (ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica, 3 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 178

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 91.

- Pr. Diego Duran, Historia Antiqua de la Nueva Espana (Madrid, 1585).

- Ixtilxochitl, Don Ferdinand d'Alva, Historia Chichimeca, 1658

- Lord Kingsborough, Antiquities of Mexico, vol. 9

- H.H. Bancroft, Native Races of the Pacific States (New York, 1874)

- Klaus Seybold, "Der Turmbau zu Babel: Zur Entstehung von Genesis XI 1–9," Vetus Testamentum (1976).

- Samuel Noah Kramer, The "Babel of Tongues": A Sumerian Version, Journal of the American Oriental Society (1968).

- Kyle Dugdale: Babel's Present. Ed. by Reto Geiser and Tilo Richter, Standpunkte, Basel 2016, ISBN 978-3-9523540-8-7 (Standpunkte Dokumente No. 5).

External links

- "Tower of Babel." Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Babel In Biblia: The Tower in Ancient Literature by Jim Rovira

- Our People: A History of the Jews – The Tower of Babel

- Livius.org: The tower of Babel

- Book of Genesis, Chapter 11

- "The Tower of Babel and the Birth of Nationhood" by Daniel Gordis at Azure: Ideas for the Jewish Nation

- SkyscraperPage – Tower of Babel, Tower of Babel – Baruch

- HERBARIUM Art Project. Anatomy of the Tower of Babel. 2010

- The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia (ISBE), James Orr, M.A., D.D., General Editor – 1915 (online)

- Easton's Bible Dictionary, M.G. Easton M.A., D.D., published by Thomas Nelson, 1897. (online)

- Nave Topical Bible, Orville J. Nave, AM., D.D., LL.D. (online)

- Smith's Bible Dictionary (1896) (online)