CTrain

CTrain is a light rail transit system in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. It began operation on May 25, 1981 and has expanded as the city has increased in population. The system is operated by Calgary Transit, as part of the Calgary municipal government's transportation department.[5] As of 2017, it is one of the busiest light rail transit systems in North America, with 306,900 weekday riders, and has been growing steadily in recent years.[6] About 45% of workers in Downtown Calgary take the CTrain to work.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg.webp) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locale | Calgary, Alberta, Canada | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Transit type | Light rail (details) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of lines | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of stations | 45[1][2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Daily ridership | 313,800 (Q4 2019)[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Annual ridership | 61,604,600 (2019)[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www.calgarytransit.com | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Began operation | May 25, 1981 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | Calgary Transit | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Train length | 3 or 4 cars | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System length | 59.9 km (37.2 mi)[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | Overhead lines, 600 V DC[4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Operations

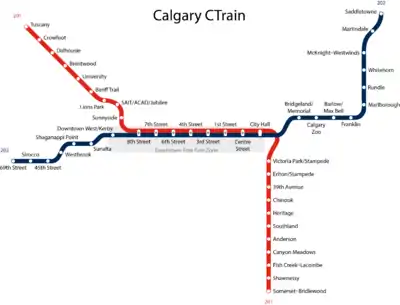

The CTrain system has two routes, designated as the Red Line and the Blue Line. They have a combined route length of 59.9 kilometres (37.2 mi).[1] Much of the South leg of the system shares the right of way of the Canadian Pacific Railway and there is a connection from the light rail track to the CPR line via a track switch near Heritage station.

The longer route (Red Line; 35 km (22 mi) serves the southern and northwestern areas of the city. The shorter route (Blue Line; 25.7 km (16.0 mi) long) serves the northeastern and western sections of the city.[7] Most track is at grade, with its own right-of-way. The downtown portion is a shared right-of-way, serving both routes along the 7th Avenue South transit mall at street level. This portion is a zero-fare zone and serves as a downtown people mover. The tracks split at the east and west ends of downtown into lines leading to the south, northeast, west and northwest residential neighbourhoods of Calgary. Six percent of the system is underground, and seven percent is grade-separated (elevated).[7] Trains are powered by overhead electric wires, using pantographs to draw power.

In the first quarter of 2015, the CTrain system had an average of 333,800 unlinked passenger trips per weekday, making it the busiest light rail system in North America.[8][9][10] Ridership has declined slightly since reaching this peak, coinciding with a recession in the local economy.[11] In 2007, 45% of the people working in downtown Calgary took transit to work; the city's objective is to increase that to 60%.[12]

Four car trains

In late 2015 Calgary Transit began operating four-car LRT trains on the CTrain system. The lengthening of trains was done to alleviate overcrowding as the system was already carrying more than 300,000 passengers per day, and many trains were overcrowded. The lengthening of trains increased the maximum capacity of each train from 600 to 800 passengers, so when enough new LRT cars arrive to lengthen all trains to four cars, the upgrade will increase the LRT system capacity by 33%. Since the platforms on the original stations were designed to only accommodate three-car trains, this required lengthening most of the platforms on the 45 stations on the system and building new electrical substations to power the longer trains. To operate the new four-car trains, the city ordered 63 new cars, although 28 of them were intended to replace the original U2 LRT cars, which have as many as 2.8 million miles on them and are approaching the end of their service lives. Many of the older stations were also worn out by high passenger traffic, and the platforms needed to be rebuilt anyway.[13]

History

The idea of rail transit in Calgary originated in a 1967 Calgary transportation study, which recommended a two-line metro system to enter service in 1978. The original plans had called for two lines:

- a northwest-to-south line (on a similar routing to the present-day Northwest and South lines) between the original Banff Trail station (at Crowchild Trail and Northland Drive, between the present-day Brentwood and Dalhousie stations) and Southwood station (at Southland Drive, roughly at the location of the present-day Southland station, with five stations in downtown underneath 7 Avenue; and

- the west line, which ran from downtown to the community of Glendale, primarily along the 26 Avenue SW corridor.

A fourth line, a north central line running from downtown to Thorncliffe mostly along Centre Street was also envisioned, but was thought to be beyond the scope of the study.

However, a building boom in the 1970s had caused the heavy rail concept to fall out of favour due to the increased costs of construction, with light rail as its replacement. LRT was chosen over dedicated busways and the expansion of the Blue Arrow bus service (a service similar to bus rapid transit today) because light rail has lower long-term operating costs and to address traffic congestion problems. The Blue Arrow service ended in 2000.

The present-day CTrain originated in a 1975 plan, calling for construction of a single line, from the downtown core (8 Street station) to Anderson Road (the present-day Anderson station). The plan was approved by City Council in May 1977, with construction of what would become the LRT's "South Line" beginning one month later. The South Line opened on May 25, 1981.[14] Oliver Bowen designed the CTrain system.

Though the South Line was planned to extend to the northwest, political pressures led to the commission of the "Northeast Line", running from Whitehorn station (at 36 Street NE and 39 Avenue NE) to the downtown core, with a new downtown terminal station for both lines at 10 Street SW, which opened on April 27, 1985.[15]

The Northwest Line, the extension of the South Line to the city's northwest, was opened on September 17, 1987, in time for the 1988 Winter Olympics.[16] This line ran from the downtown core to University station, next to the University of Calgary campus. Since then, all three lines have been extended incrementally, with most of the stations commissioned and built in the 2000s (with the exception of Brentwood which opened in 1990, three years after the original Northwest line opened):

| Date | Stations | Line |

|---|---|---|

| August 31, 1990 | Brentwood | Northwest Line |

| October 9, 2001 | Canyon Meadows Fish Creek–Lacombe | South Line |

| December 15, 2003 | Dalhousie | Northwest Line |

| June 28, 2004 | Shawnessy Somerset–Bridlewood | South Line |

| December 17, 2007 | McKnight–Westwinds | Northeast Line |

| June 15, 2009 | Crowfoot | Northwest Line |

| August 27, 2012 | Martindale Saddletowne | Northeast Line |

| August 25, 2014 | Tuscany | Northwest Line |

The West Line, the extension of the Northeast Line, opened for revenue service on December 10, 2012 as the first new line to open in 25 years. The line runs for 8.2 km from Downtown West-Kerby station on 7 Avenue at 11 Street SW at the west end of Downtown, westward to 69 Street station located at the intersection of 17 Avenue and 69 Street SW.

Rolling stock

| Fleet numbers | Total | Type | Year Ordered | Year Retired | Number of units Retired | Exterior | Interior | Origins | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001–2083, 2090 | 83 | Siemens–Duewag U2 | 1979–1985 | Started 2016 | 44 |  |

|

Düsseldorf, Germany | 1 Unit formed from other Units (see below)

Retired units are up to date as of March 24, 2020 |

| 2101-2102 | 2 | Siemens–Duewag U2 AC | 1988 | 2016 | 1 |  |

|

Düsseldorf, Germany | Use AC traction instead of DC traction

Former demonstration trains 2101 is now an asset inspection train named Scout. It inspects the wires and tracks. Only variants in the world |

| 2201–2272 | 72 | Siemens SD-160 Series 5/6/7 | 2001–2006 | - | - |  |

|

Florin, California | Refurbished 2009–2010 in-house.

32 to be refurbished by Siemens. |

| 2301–2338 | 38 | Siemens SD-160NG Series 8 | 2007 | - | 1 |  |

|

Florin, California | 2311 retired due to an accident (see below) |

| 2401-2469 | 69 | Siemens S200 | 2013-2018 | - |  |

|

Florin, California |

2401-2463 built and delivered between 2015 and 2019; 2464-2469, 2019-2020 Some units are out of service for temporary use as parts vehicles |

The system initially used Siemens-Duewag U2 DC LRVs (originally designed for German metros, and used by the Frankfurt U-Bahn. The slightly earlier Edmonton Light Rail Transit, and the slightly later San Diego Trolley were built at approximately the same time and used the same commercial off-the-shelf German LRVs rather than custom-designed vehicles such as were used on the Toronto streetcar system and the Vancouver Skytrain. U2 vehicles constituted the entire fleet in Calgary until July 2001, when the first Siemens SD-160 cars were delivered.[7] Eighty-three U2 DCs were delivered to Calgary over three separate orders; 27 in 1981, three in 1983, and 53 in 1984 and are numbered 2001 – 2083. As of March, 2020, 39 out of the original 83 U2 DCs remain in service, plus car 2090. The success of the first North American LRT systems inspired Siemens to build an LRV plant in Florin, California. Siemens now supplies one-third of North American LRVs and has supplied over 1000 vehicles to 17 North American systems.[17] This will include 258 vehicles for Calgary when the current order of Siemens S200 vehicles is completed. The following LRVs have been retired:

| Car Number | Type | Year Retired | Reason | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001, (2002), 2004, 2006, 2008, 2011, 2014, 2016, 2017, 2022, 2023, 2026, 2029, 2033-2037, 2040, 2042, 2043, 2045, 2049, 2052, 2055, (2064), 2065, (2066), 2067, 2069, 2072, 2074-2079, (2080), 2081, 2083. | U2 | 2016-present | Retired as a result of newer S200 LRVs. | Retired. Being salvaged for parts and scrapped. |

| 2002 | U2 | May, 1981 / September, 2019 | Collided with car 2001 in May, 1981; A-end written off. B-end later received a new A-end and was retired at end of life in 2019. | Retired; disposed of in 2020. A-end was scrapped, B-end was sold to a private owner, who is creating a piece of street-art using it as a part of a thesis project.[18] |

| 2010 | U2 | March 27, 2002 | Collided with a truck at the 4 Avenue SW crossing as it was leaving the Downtown. | Retired. Used as spare parts. |

| 2019 | U2 | April 2007 | Collided with a flatbed truck in the intersection of Memorial Drive/28 Street SE near Franklin Station. | Retired. One end is used as spare parts, the other end was combined with the good end of LRV 2027 to form LRV 2090. |

| 2027 | U2 | May 2008 | Damaged when it hit a crane in the median of Crowchild Trail near Dalhousie Station | Retired. One end is used as spare parts, the other end was combined with the good end of LRV 2019 to form LRV 2090. |

| 2050 | U2 | October 2007 | Collided with a vehicle at the 58 Avenue SW crossing near Chinook Station. | Repaired in 2010; currently active |

| 2057 | U2 | Summer of 2009 | Damaged when it hit a backhoe that was being used in the construction of the new 3 Street W station on 7 Avenue downtown. | Retired. Used as spare parts. |

| 2064, 2066, 2080[19] | U2 | Summer 2018 | Sold to Edmonton Transit Service after they were retired at end of life,[20] used for parts, and have since been scrapped. | |

| 2101 | U2 AC | Early 2016 | Taken out of service. | Converted to track inspection vehicle (named SCOUT) |

| 2102 | U2 AC | August 8, 2016 | Taken out of service. | Retired in early 2017. Used as spare parts for 2101, has since been scrapped. |

| 2311 | SD-160NG | September 20, 2016 | Departed Tuscany Station into the tail track, and overshot the end of the rails crashing into the tail fence and a metal power pole at the end of the rails. | Retired, scrapped. |

Note: units in parentheses in the first row in the above table were retired at end of life, but are also listed in rows below.

In 1988, the Alberta Government purchased from Siemens two U2 AC units, the first of their kind in North America, for trials on both the Edmonton and Calgary LRT systems. The cars were originally numbered 3001 and 3002 and served in Edmonton from 1988 to Spring 1990. These LRVs came to Calgary in the summer of 1990 and in September, Calgary Transit decided to purchase the cars from the Province and then applied the CT livery to the cars (they were previously plain white in both Edmonton and Calgary). They retained their original fleet numbers of 3001 and 3002 until 1999, when CT renumbered the cars 2101 and 2102. Initially, these two cars were only run together as a two-car consist as they were incompatible with the U2 DCs. In 2003, Calgary Transit made the two U2 ACs compatible as slave cars between two SD160s and have been running them like this ever since.

In July 2001, Calgary Transit brought the first of 15 new SD160 LRVs into service to accommodate the South LRT Extension Phase I and increased capacity. Throughout 2003, another 17 SD160 LRVs were introduced into the fleet to accommodate the NW Extension to Dalhousie as well as the South LRT Extension Phase II. However, demand for light rail has exploded in recent years. In the decade prior to 2006, the city's population grew by 25% to over 1 million people, while ridership on the CTrain grew at twice that rate, by 50% in only 10 years. This resulted in severe overcrowding on the trains and demands for better service.[21] In December, 2004, city council approved an order for 33 additional SD-160 vehicles from Siemens to not only address overcrowding, but to accommodate the NE extension to McKnight–Westwinds and the NW extension to Crowfoot. These new SD160s started to enter service in November, 2006. In December 2006, CT extended the order by seven cars to a total of 40 cars, which had all been delivered by the spring of 2008. This brought the total of first-generation SD 160s to 72 cars numbered 2201 – 2272. These cars were all delivered without air conditioning, and retrofitted with air conditioning between 2009 and 2011.[22][23][24]

In November 2007 city council approved purchasing another 38 SD-160 Series 8 LRVs to be used in conjunction with the West LRT extension (2012) and further expansions to the NE (Saddletowne 2012) and NW legs (Tuscany 2014). These are new-generation train cars with many upgraded features over the original SD160s including factory equipped air conditioning and various cosmetic and technical changes.[25] These units started to enter service in December 2010 and are numbered 2301–2338. As of May 2012, all have entered revenue service and Calgary's LRV roster now numbers 192.

In September 2013, Calgary Transit ordered 63 S200 LRVs to provide enough cars to run four-car trains, and to retire some of its Siemens-Duewag U2s, which are nearing the end of their useful lifespans.[26][27] Some of the 80 U2 cars were 34 years old, and all of them had traveled at least 2,000,000 kilometres (1,200,000 mi). The first of the new cars arrived in January, 2016 and delivery was expected take two years. The front of the new cars is customized to resemble a hockey goalie's mask, and they include such new features as heated floors for winter and air conditioning for summer. They also now have high-resolution video cameras covering the entire interior and exterior of the vehicles for security purposes.[28]

On November 18, 2016, Calgary Transit announced the retirement of the first CTrain purchased, car 2001. Some of the Siemens Duwag U2 cars will be phased out as the new Siemens S200 cars come online.[29]

- Work cars

- Car# 3275 – shunting/switcher locomotive

Facts

In 2001, the CTrain became the first public transit system in Canada to purchase all of its electricity from emissions-free wind power generation. The electricity is generated by Enmax operating in southern Alberta.[30][31] The trains are powered from the same power grid as before; however, an equivalent amount of electricity is produced at the southern wind farms and "dedicated" to the CTrain. Under Alberta's deregulated market for electricity, large consumers can contract to purchase their electricity from a specific vendor.

On February 18, 2009, Calgary Transit announced that the CTrain had carried one billion riders in the 28 years since the start of service on May 25, 1981.[32] The trains were now carrying over 269,600 passengers every day, higher than any other light rail system in Canada or the United States. Mayor Dave Bronconnier stated that more vehicles were on order to deal with crowding, the northeast and the northwest legs were being extended, and construction of the new west leg was due to start later in the year.[33]

In the following section preliminary timelines for construction of future stations are referenced. For example, construction of a north CTrain line is not expected until after 2023. The city has, on several occasions, accelerated construction of CTrain expansion due to demand and available money. For example, the McKnight-Westwinds station, which opened in 2007, was, as recently as 2002, not planned until beyond 2010. Similarly, the timeline of construction of the south line extension was also pushed up several years due to increasing population and traffic volume. There are plans to develop new routes into the centre north and the southeast of the city.

Fares

Rides taken solely within the downtown are free. This is known as the 7th Avenue Free Fare Zone and encompasses all CTrain stations along 7th Avenue.[34]

Route details

There are two light rail lines in operation: the Red Line running from the far southern to the far northwestern suburbs of Calgary (Somerset/Bridlewood–Tuscany), and the Blue Line running from the northeastern to the western suburbs (Saddletowne–69 Street). The routes merge and share common tracks on the 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) downtown transit mall on 7th Avenue South, which also allows buses and emergency vehicles.[7]

Downtown Transit Mall

As part of the construction of the original South leg, nine single-platform stations were built along the 7th Avenue South transit mall, which formed the 7th Avenue free fare zone. All nine stations opened May 25, 1981. The tracks run at grade in a semi-exclusive right of way, shared with buses, city and emergency vehicles. This is a free-fare zone intended to act as a downtown people mover. Fares are only required after trains exit the downtown core.

Westbound stations used to consist of Olympic Plaza (formerly 1 Street E, renamed in 1987), 1 Street W, 4 Street W, and 7 Street W. Eastbound stations consisted of 8 Street W, 6 Street W, 3 Street W, Centre Street and City Hall (formerly 2 Street E, renamed in 1987).

When the Northeast leg opened on April 27, 1985, two stations were added: 3 Street E serving Westbound Blue Line trains only and 10 Street W, a centre-loading platform, which served as the terminus of both Red and Blue lines, until the Northwest leg opened in 1987, after which it was the terminus for the Blue line only.

As part of Calgary's refurbishment project,[35] 3 Street E and Olympic Plaza stations have been decommissioned and replaced by the new gateway[36] City Hall station in 2011. 10 Street W was decommissioned and replaced with the Downtown West–Kerby (formerly called 11 Street W) station in 2012.[37]

Downtown station refurbishment

In June 2007, the City of Calgary released information on the schedule for the refurbishment of the remaining original downtown stations.[38] The plan involved replacing and relocating most stations, and expanding Centre Street station which was relocated one block east (adjacent to the Telus Convention Centre) in 2000, to board four-car trains. The new stations have retained their existing names (with the exception of 10 Street W becoming Downtown West–Kerby in 2012); however, they may be shifted one block east or west, or to the opposite side of 7th Avenue. The refurbishment project was completed on December 8, 2012, when the Downtown West–Kerby station was opened to the public in conjunction with the West LRT opening event.[39]

- 1 Street SW – new platform relocated one block east opened October 28, 2005.

- 7 Street SW – new platform relocated one block east opened February 27, 2009.

- 6 Street SW – reconstructed in original location. Original platform closed April 7, 2008 and new platform opened March 27, 2009.

- 8 Street SW – new platform relocated one block east opened December 18, 2009.

- 3 Street SW – reconstructed in original location. Original platform closed April 20, 2009 and new platform opened March 12, 2010.

- 3 Street SE – permanently closed May 3, 2010. Replaced by new dual-platform City Hall Station opening July 6, 2011.

- 4 Street SW – reconstructed in original location. Original platform closed January 7, 2010 and new platform opened January 21, 2011.

- City Hall – original Eastbound platform rebuilt with new Westbound platform to replace 3 Street E and Olympic Plaza. Original platform closed May 3, 2010 and new dual-platform station opened July 6, 2011. Olympic Plaza was closed permanently at this time. Eastbound platform re-closed following the 2011 Stampede to finish construction and officially opened September 19, 2011.

- Olympic Plaza – permanently closed July 6, 2011. Replaced by new dual-platform City Hall Station.

- 10 Street SW – permanently closed and removed on September 15, 2012.[37][40] The new station replacing it, which opened on December 8, 2012, has dual side-loading platforms and is located one block west. This project was initially proposed to be undertaken in 2006, following the opening of the new 1 Street W station. However, the City of Calgary decided to defer the project to coincide with the opening of the West Line and continue on with refurbishment of the other stations. This new station was initially called "11 Street W" up until the Summer of 2012 when it was renamed to Downtown West–Kerby.[41]

This required that the stations be closed during demolition and reconstruction. The new stations feature longer platforms for longer trains, better integration of the platforms into the sidewalk system, better lighting, and more attractive landscaping and street furniture. This project was shortlisted[42] for the New/Old category in the 2012 World Architecture Festival in Singapore.[43]

Red Line

Also known as Route 201, this route comprises two legs connected by the downtown transit mall: the South leg (17.3 kilometres (10.7 mi)) and the Northwest leg (15.7 kilometres (9.8 mi)). There are eleven stations on the South leg and nine on the Northwest leg. Total length of the line: 33 kilometres (21 mi).[7]

South leg

This was the first leg of the system to be built. Seven stations on this leg opened on May 25, 1981, as the first light railway line to serve the city. From north to south, they are Victoria Park/Stampede (renamed from Stampede in 1995), Erlton/Stampede (renamed from Erlton in 1995), 39 Avenue (renamed from 42 Avenue in 1986), Chinook, Heritage (also the site of the Haysboro LRT Storage Facility), Southland, and Anderson (also the site of the Anderson LRT Yards). The original South line was 10.9 km long. On October 9, 2001, the line was extended south 3.4 km and two new stations were added: Canyon Meadows and Fish Creek–Lacombe, as part of the South LRT Extension Phase I. On June 28, 2004, Phase II opened adding 3 km of track and two more stations: Shawnessy and Somerset–Bridlewood. A further three stations – Silverado (most likely in the area of 194th Avenue SW), 212th Avenue South, and Pine Creek (in the area around 228th Avenue SW) – are planned once the communities adjacent to their location are developed, likely beyond 2020.[44]

Northwest leg

This was the third leg of the system to be built. Five stations on this leg opened on September 7, 1987. From the most central to the most northwesterly, they are Sunnyside, SAIT/AUArts/Jubilee (the station name in full is "Southern Alberta Institute of Technology/Alberta University of the Arts/Jubilee Auditorium"), Lions Park, Banff Trail, and University. The original Northwest leg was 5.6 km long. On August 31, 1990, the line was extended 1 km and Brentwood station was opened as the new terminus. On December 15, 2003, the line was extended 3 km again and Dalhousie station was opened. On June 15, 2009, the line was extended 3.6 km and Crowfoot (formerly Crowfoot-Centennial) was opened. It was extended further by 2.5 km to Tuscany Station on August 25, 2014.[45][46][47]

Blue Line

Also known as Route 202, this route is composed of two legs connected by the downtown transit mall: the Northeast leg (15.5 kilometres (9.6 mi)) and the newer West leg (8.2 kilometres (5.1 mi)). The Northeast leg has ten stations and the West leg has six stations. Total length of this route: 25.7 kilometres (16.0 mi).[7]

Northeast leg

This was the second leg of the system to be built. Seven stations opened on April 27, 1985, from downtown to the northeast. They are: Bridgeland/Memorial, Zoo, Barlow/Max Bell, Franklin, Marlborough, Rundle, and Whitehorn. The original Northeast line was 9.8 km long. On December 17, 2007, the line was extended 2.8 km further north to an eighth station – McKnight–Westwinds. On August 27, 2012, another 2.9 km extension of track opened and added two more stations – Martindale and Saddletowne.[46][48][49] Additional stations are proposed for development, likely beyond 2023, at 96th Avenue, Country Hills Boulevard, 128th Avenue (north of Skyview Ranch) and Stoney Trail (in the Stonegate Landing development),[48] as those areas are developed for future LRT infrastructure.[50]

West leg

This was the fourth leg of the system to be built, although it was included in the original plans for the system.[51] It was built last because it was anticipated to have lower ridership and higher construction costs than the previous legs. Construction of the 8.2 kilometre[52] (5 mile) leg began in 2009. It opened on December 10, 2012.[53]

The City of Calgary began a review process in late 2006 to update the plans to current standards, and Calgary City Council gave final approval to the project[54] and allocated the required $566-million project funding on November 20, 2007.[46] Funding for the project was sourced from the infrastructure fund that was created when the Province of Alberta returned the education tax portion of property taxes to the city. Construction of this leg began in 2009. It was constructed at the same time as further extensions of the NE and NW lines of the LRT system that were approved in November 2007.

The West LRT leg[55] has six stations (from east to west): Sunalta (near 16th Street SW), Shaganappi Point, Westbrook, 45 Street (Westgate), Sirocco, and 69 Street (west of 69th Street near Westside Recreation Centre).

The updated alignment from the 2007 West LRT Report[48] includes the line running on an elevated guideway beginning west of the Downtown West–Kerby Station, running along the CPR right of way to Bow Trail SW, and then to 24th Street SW. The line then runs at grade past Shaganappi Point Station and drops into a tunnel to 33rd Street SW. The tunnel then runs under the Westbrook Mall parking lot, and the former site of the now-demolished Ernest Manning Senior High School. The line then follows the north side of 17th Avenue SW past 37th Street SW below grade to 45 Street station. Past 45th Street the line runs at grade, and approaching Sarcee Trail SW moves onto an elevated guideway that passes over the freeway. The line then runs at grade to Sirocco Station, then proceeds to drop below grade and pass under eastbound 17th Avenue SW at 69th Street SW and return to grade on the south side of the avenue. The line then terminates at 69 Street Station located to the west of 69th Street SW.[56]

Three of the new West leg stations are located at grade. Westbrook, 45 Street,[57] and 69 Street stations are located below grade, while Sunalta is an elevated station.[58] On October 5, 2009, the city council announced approval of a plan to put a portion of the West leg into a trench at 45th Street and 17th Avenue SW, a move welcomed by advocates who fought to have it run underground. The change cost an estimated $61 million; however, lower-than-expected construction costs were expected to absorb much of the change.

The cost for the project is, however, over budget by at least C$35 million[59] and the overall cost could be more than C$1.46 billion because of soaring costs of land used and the integration of public art into the project.[60][61][62] The public art aspect of the project was neglected in its initial form. Because City Hall regulations for big construction projects require incorporation of public art, City Hall had to find the money. Therefore, the West LRT project cost C$8.6 million more than expected.[63][64]

On October 29, 2009 city council announced that the contract to construct the West LRT had been awarded to a consortium led by SNC Lavalin.[65]

Future extension of the West leg to Aspen Woods Station (around 17th Avenue and 85th Street SW) has been planned, and future extensions further west to 101st Street SW may be added as new communities adjacent to 17th Avenue SW are built.[56]

On May 15, 2012, testing of the leg began with two LRT cars. As the construction of the leg moved towards completion, four LRT cars were used, until revenue service began on December 10, 2012.[66][67][68][69]

In its first year of service, 69 Street served an average of 32,400 boardings per day.[70]

Future plans

.svg.png.webp)

In 2011, Calgary City Council directed that a long term Calgary Transit Plan be created, taking into account the overall Calgary Transportation Plan.[71][72] A steering committee and project team, comprising some Council members, City planning staff, independent business people and Calgary Transit staff, after detailed scenario planning and extensive public consultation, produced the December 2012 "RouteAhead: A Strategic Plan for Transit in Calgary".[71][72] A 30-year roadmap for public transit in Calgary, RouteAhead includes a long term vision for the CTrain system. The RouteAhead plan was submitted to Council and approved in early 2013.[72]

Existing Lines

For the Red Line, in its 30-year RouteAhead plan, the South line may be extended another 3.5 km to a possible 210 Avenue SW station.[73]

For the Blue Line, from the same plan, there are more possible extensions to the northeast to either Calgary International Airport (via a spur line),[74] or to 128 Avenue NE, or to have both.[75]

There are plans to build an additional line to the southeast from the city centre. Calgary Transit has drafted a plan for a transit-only right-of-way, known as the SETWAY (South East Transit Way) for the interim.[76] A second, northern line is to be planned beyond 2023 but the alignment is still pending.

As for a possible underground leg in downtown (under 8 Avenue South), the cost of the project will be at least C$800 million (in 2012 dollars), but its priority has been lowered because there is no funding available for it. However, the overall cost of this and other projects could be at least C$8 billion.[74][75]

Green Line

Green Line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This proposed future route would cross the downtown core at right angles to the downtown transit mall and connect two new legs: the Southeast leg and the North-Central leg. It would exceed the capacity of the downtown transit mall, requiring that it use a new right of way going over or under the existing transit mall. Elevated tracks would conflict with Calgary's downtown +15 system, which is the most extensive pedestrian skywalk system in the world, so this option is unlikely. Most likely the system will go underground, crossing underneath the future downtown subway, which already has a short section of tunnel built under 8th Avenue S and a ghost station under the Calgary Municipal Building. The exact routes and station locations are currently in the planning stages.[77]

Funding has been secured for the first stage of construction of the Green Line stretching from 16th avenue North through the downtown core into the Southeast to the future Shepard Station at 126th Avenue SE. It is expected to be complete by 2026. The $4.6 billion cost of the project will be shared in roughly equal portions between the federal government, the city of Calgary and the provincial government.[78]

North leg

This leg of the Green Line would serve the residential communities of Country Hills, Coventry Hills, Harvest Hills, Panorama Hills, and other communities, possibly in the future extending as far as the nearby City of Airdrie. The Green Line North, as it has been re-designated, will be a mix of grade level and underground infrastructure extending north from the downtown core along Centre Street North.

In July 2015, the Canadian federal government committed to put $1.5 billion into funding the Green Line LRT or one-third of the project's $4.6 billion cost.[79] Discussions between the city of Calgary and the province continue with the goal of building the new light rail line instead of developing a BRT system as an interim measure.

In January, 2015, Calgary City Council approved the Green Line North (formerly known as North Central LRT), setting Centre Street N. as the route. In December, 2015 Council approved the planning report on Green Line funding, staging, and delivery. The North leg is expected to be the first section of the Green Line to be built. Actual completion dates will depend on delivery of promised federal and provincial government funding.[80]

Southeast leg

This leg is planned to run from downtown (although on a different routing, not following the 7th Avenue corridor) to the communities of Douglasdale and McKenzie Lake and McKenzie Towne in the southeast, and onwards past Highway 22X into the so-called "Homesteads" region east of the Deerfoot Trail extension.

Eighteen stations have been planned for this route and the project is expected to be completely built by 2039.[81]

Three of the proposed downtown stations are expected to be built underground,[82] and the rest of the line will follow the 52 Street SE corridor from Douglasdale and McKenzie Towne to Auburn Bay (south of Highway 22X) and then wind its way through Health Campus (adjacent to the southeast hospital) and Seton. Unlike Routes 201 and 202, which use high-floor U2 and SD-160 LRVs, the eastern route is expected to employ low-floor LRVs,[83] such as the Bombardier Flexity Outlook or the Siemens S70.

From north to south, the proposed stations are: Eau Claire, Central (at 6 Avenue), Macleod Trail, 4 Street SE, Ramsay/Inglewood, Crossroads, Highfield, Lynnwood, Ogden, South Hill, Quarry Park, Douglasglen, Shepard, Prestwick, McKenzie Towne, Auburn Bay/Mahogany (at 52nd Street), Health Campus/Seton (the station likely will share the name of the hospital and expected to be completed by 2039),[81] with further stations to the south expected in the future.[84][85]

Construction of the South East LRT would cost over C$2.7 billion over 27 years.[81] Because there was no funding available, the city laid out plans to build a transit way for the South East BRT known as SETWAY. Open houses to explore the idea of a transit way for the South East occurred in the South East communities of Ramsay, Riverbend and McKenzie Towne in January 2012. Between 1999 and 2006 Calgary Transit conducted studies for the South East LRT to find ways to make improvements of overall transit use in the South East for short term while having LRT being the long-term goal.[76]

On December 3, 2016, it was announced that an additional C$250 million in additional funding was allocated in a joint venture by the Federal and Provincial Governments. This comes in line with a possible final cost estimate of the South East LRT to be announced in March 2017.

Spur line to Calgary International Airport

Calgary Transit's C$8 billion, 30-year RouteAhead plan, approved in 2013, includes a connection from downtown Calgary to Calgary International Airport, which may take initial form as a Route 202 spur line.[74][75] The Airport Trail road tunnel, which opened on May 25, 2014, was built with room to accommodate a future two-track CTrain right-of-way.[86]

Other future improvements

In late 2015, Calgary Transit completed upgrading its entire system to operate four-car trains instead of the original three-car trains. When enough new LRVs are delivered to lengthen all trains to four cars, this will increase the rush-hour capacity of the system by 33%. By 2023, Calgary Transit also plans to begin decommissioning some of the original Siemens-Duewag U2s (as of 2010 80 of the original 83 were in use, and nearing 29 years of service, by 2023 they will be 42 years old). Calgary Transit has ordered some 60 new Siemens S200 LRV cars to replace 28 of the existing U2s in addition to lengthening many of the trains to four cars.[87][88] Calgary transit has also integrated a new mobile ticketing system which allows riders to buy CTrain and other Calgary Transit tickets and passes anytime from anywhere with the use of a smartphone.[89] This system, dubbed "My Fare" was rolled out at the end of July 2020, but faced issues at launch such as the incompatibility with Apple's iOS devices.[90]

Further underground infrastructure

In addition to numerous tunnels to allow trains to pass under roadways, geographic features, and mainline railways, there are other notable underground portions of Calgary's CTrain system.

Part of the system through downtown is planned to be transferred underground when needed to maintain reliable service. Given this, portions of the needed infrastructure have been built as adjacent and associated land was developed.[91] As a result of this original plan, when the City of Calgary built a new Municipal Building, it built a short section of tunnel to connect the existing CPR tunnel to the future tunnel under 8th Avenue S. The turnoff to this station is visible in the tunnel on the Red Line entering downtown from the south, shortly before City Hall. However, after urban explorers discovered the tunnel and visited it during a transit strike, the city walled off the spur tunnel with concrete blocks.

As the population of metropolitan Calgary increases and growing suburbs require new lines and extensions, the higher train volumes will exceed the ability of the downtown section along 7th Avenue S to accommodate them. To provide for long-term expansion, the city is reviewing its plans to put parts of the downtown section underground. The current plans allow the expanded Blue Line (Northeast/West) to use the existing 7th Avenue S surface infrastructure. The expanded Red Line (Northwest/South), now sharing 7th Avenue S with the Blue Line, will be relocated to a new tunnel dug beneath 8th Avenue S. The future Southeast/Downtown route will probably enter downtown through a shorter tunnel under one or more streets (candidates include 2nd Street W, 5th Street W, 6th Street W, 8th Avenue S, 10th Avenue S, 11th Avenue S, and 12th Avenue S). Although Calgary City Council commissioned a functional study for the downtown metro component of the CTrain system in November 2007, the city is unlikely to complete this expansion before 2017 unless additional funding is received from provincial or federal governments. The cost of bringing the potential underground leg under 8 Avenue South could be at least C$800 million, according to Calgary Transit's 30-year RouteAhead plan.[74][75]

CTrain stations

There are 45 stations in the CTrain system on 2 distinct lines. The typical station outside the downtown core allows for several methods of passenger arrival and departure. Many CTrain passengers travel to and from suburban stations on feeder bus routes that wind their way through surrounding neighbourhoods. Another popular option is a Park and Ride lot, in which commuters drive to a station by car and then transfer to a CTrain to complete their journey. Alternatively, some CTrain passengers disembark at drop-off zones from vehicles travelling elsewhere; because many of these commuters are conveyed by their spouses, these zones are branded as Kiss and Ride areas.

Ridership

The CTrain's high ridership rate and cost effectiveness can be attributed to a number of factors. The nature of Calgary itself has encouraged CTrain use. Calgary has grown into the second largest head office city in Canada, with a very dense downtown business district. Most of the head offices are crowded into about 1 square kilometre (250 acres) of land in the downtown core. In the last half century the population of Calgary has grown dramatically, outpacing the ability of roads to transport people into the city centre, while the central business district has grown up vertically rather than spread out into the suburbs.[92]

Historically, Calgary residents, particularly its influential inner city community associations, voted against proposals to build major freeways into its city centre, forcing new commuters to use transit as their numbers increased while downtown street and freeway capacity remained the same. City planners limited the number of parking spaces in the downtown core since the narrow downtown streets could not allow more traffic to park. At the same time, Calgary's maturation as a globally influential head office city caused many surface parking lots to be replaced by new skyscrapers, which increased office workers while reducing parking spaces. This eventually made it prohibitively expensive for most people to park downtown. The shortage of downtown parking caused fees to become among the most expensive in North America.[93][94] As a result, in 2012 50% of Calgary's 120,000 downtown workers used Calgary Transit to get to work, with a long-term goal of growing that proportion to 60% of downtown workers.

Forward planning for the CTrain played an important role. Although the light rail system was not chosen until 1976, the city planners had proactively reserved transit corridors for some form of high capacity transport during the 1960s, and the right-of-ways for the system were reserved when Calgary's population was less than 500,000, whereas today it is well over twice that number. Bus rapid transit lines were put in place along future routes to increase commuter numbers prior to constructing proposed future LRT lines. Rather than demolishing buildings, the city reached an agreement with CP Rail to build most of the south line in available space inside an existing CPR right-of-way. Large parts of the other lines were built in the medians and along the edges of freeways and other major roads. Automobile driver objections were muted by adding extra lanes to roads for cars at the same time as putting in the LRT tracks, which reduced costs for both, and by adding grade-separating intersections which reduced both driver and train delays. The lines and stations were placed to serve large outlying suburbs and the central and other business districts, and to serve existing and predicted travel patterns.

Costs were controlled during construction and operation of the system by going with the lowest bidder and using relatively cheap, commercially available technology without regard for "buy Canadian" policies. This has worked out well for a pioneer system because the German technology chosen has since become a more or less standard design for most North American LRT systems, and compatible new-generation equipment with new features is available off-the-shelf. A grade-separated system was passed over in preference for a system with few elevated or buried segments, and the trains and stations selected were of the tried and tested, utilitarian variety (for example, vehicles were not air conditioned, storage yards were not automated, and stations were usually modest concrete platforms with a shelter overhead). This allowed greater amounts of track to be laid within available budgets. The CTrain reduced fare collection costs by using an honour system of payment. Transit police check passenger tickets at random, and fines are set at a level high enough that those who are caught pay the costs for those who evade detection. Staffing costs were kept low by employing a minimum number of workers, and because the system is all-electric (wind powered) it can run all night with only 1 driver per train and 2 people in the control room. It now runs 22 hours per day without significantly increased overhead. (The other 2 hours are reserved for track maintenance).

Although not universally grade separated, the CTrain is able to operate at high speeds on much of its track because it is separated from traffic and pedestrians by fences and concrete bollards. The downtown 7th Avenue transit way is limited to trains, buses, and emergency vehicles, with private cars prohibited. Trains are given priority right of way at most road crossings outside of downtown. As a result, trains are able to operate at 80 km/h (50 mph) outside of downtown, and 40 km/h (25 mph) along the 7th Avenue corridor. 7th Avenue is a free fare zone, intended as a downtown people-mover to encourage use for short hops through the downtown core. The city manages to achieve very high transit capacity on the 7th Avenue transit corridor by staging the traffic lights, so that all the trains move forward in unison to the next station on the synchronized green lights, and load and unload passengers on the intervening red lights. The trains are now 1 block long, but buses occupy the empty gaps every second block between trains and the buses unload and load passengers while the trains pass them.[95]

In 2001, the U.S. General Accounting Office released a study of the cost-effectiveness of American light rail systems.[96] Although not included in the report, Calgary had a capital cost of US$24.5 million per mile (year 2000 dollars), which would be the sixth lowest (Edmonton was given as US$41.7 million per mile). Because of its high ridership (then 188,000 boardings per weekday, now over 300,000) the capital cost per passenger was $2,400 per daily passenger, by far the lowest of the 14 systems compared, while the closest American system was Sacramento at $9,100 per weekday passenger). Operating costs are also low, in 2005, the CTrain cost CDN$163 per operating hour to operate. With an average of 600 boardings per hour, in 2001 cost per LRT passenger was CDN$0.27, compared to $1.50 for bus passengers in Calgary.[95]

Signals

Block signals

The line is subdivided into blocks. A red/yellow/green signal protects the entry to each block, with three possible aspects:

- Red: Stop (next block is occupied)

- Yellow: Approach (max 60 km/h, next block is clear, but the following block is occupied)

- Green: Clear (at least next two blocks are clear)

Interlocking signals

Two red/yellow/green signals positioned vertically are at the entry of interlockings.

- Red over Red: Stop (no routing selected, block of selected route occupied)

- A flashing white letter R below the signal shows that the railroad switch is repositioning and the signal will change soon.

- Red over Yellow: Restricted (no signal protection)

Straight through routing

- Yellow over Red: Approach (max 60 km/h, next light is red/next block is occupied)

- Green over Red: Clear (at least next 2 blocks are unoccupied)

Cross-over routing

- Red over Flashing Yellow: Slow Approach (next signal is red/next block is occupied)

- Red over Flashing Green: Slow Clear (at least next 2 blocks are unoccupied)

In-street signals

Flashing yellow is effectively an early yellow light for trains, which are longer than other vehicles using the intersection and need more time to clear the intersection at in-street limits track speed (40 km/h).

- Red, Yellow: Stop

- Green and Flashing Yellow: Stop if possible

- Green: Go

Lunar signals

At a rail crossing, Horizontal means "level crossing not protected", and Vertical means "level crossing protected". When gates are broken or a gate arm stuck up, they will remain Horizontal. Proceeding through an unfavorable lunar signal is permitted at a restricted speed (5 km/h) with caution.

At manual switches, Vertical means "straight through movement" and Diagonal (in either direction) means "cross over movement"

More modern Lunar signals are found on new parts of the right of way. For example, at the 45 Street level crossing, solid lines replace the dual lights.

Speed

A yellow diamond with a black number shows the maximum speed limit in km/h.

Large colored rectangles (typically as temporary signals) also show the maximum speed limit:

- Red: 5 km/h

- Yellow: 30 km/h

- Blue: 50 km/h

- Green: 80 km/h

Facilities

- Anderson Garage – LRV indoor storage and training facilities

- Haysboro Garage – small indoor and outdoor LRV storage; LRV yard and Turner Storage Area

- Oliver Bowen Maintenance Centre – major LRV repair and shops; storage for 60 cars (and up to 108 cars after expansion)

See also

- Calgary municipal railway

- Light rail in Canada

- Light rail in North America

- List of tram and light-rail transit systems

References

- "About Calgary Transit / Facts and Figures / Statistics". Calgary Transit. City of Calgary. 2015. Retrieved July 17, 2015.

- "CTrain Map" (PDF). Calgary Transit. City of Calgary. August 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- "Public Transportation Ridership Report – Fourth Quarter, 2019" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. May 31, 2020. p. 37. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- "SD160 Light Rail Vehicle: Calgary, Canada" (PDF). Siemens Transportation Systems, Inc. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 26, 2010. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

Catenary supply voltage: 600 Vdc

- "The City of Calgary Transportation Department". City of Calgary (website). March 21, 2011. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- "Transit Ridership Report, p. 32" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. June 6, 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 29, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- "LRT Technical Data". Calgary Transit. City of Calgary. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014.

- "Transit Ridership Report, First Quarter 2015" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. May 27, 2015. p. 31. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 18, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- "Transit Ridership Report, Fourth Quarter 2013" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. February 26, 2014. p. 31. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- "Banco de Información Económica - Instituto Nactional De Estadística Y Geografía - Comunicaciones y transportes". Instituto Nactional De Estadística Y Geografía (INEGI). Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- "Calgary Transit looking to bolster revenue in wake of falling ridership". Cagary Sun. May 13, 2017. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- Kom, Joel (January 2, 2008). "Residents forced to cope with growing traffic crunch - City confident it can handle growth". Calgary Herald. Archived from the original on September 12, 2015. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- "Calgary Transit Launches Four-Car Service Early". The City of Calgary. November 13, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- History Calgary Transit

- Calgary Light Rail Expansion Pacific RailNews issue 263 October 1985 page 29

- Interurbans Newsletter Pacific RailNews issue 289 December 1987 page 46

- "Light rail vehicles and streetcars". Siemens. Archived from the original on May 12, 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- "Decommissioned CTrain car a dream canvas for Calgary artist | CBC News".

- Panchyshyn, Corey (July 17, 2018). "Calgary LRV 2066 Delivered to Edmonton". flickr. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- "CTrain - U2 cars Retirement Watch". CPTDB. July 17, 2018. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- Guttormson, Kim (January 20, 2007). "Transit hit by 10% rise in riders - City struggles to provide service amid staff crunch". Calgary Herald. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- "C-Train Siemens-Duewag SD160".

- "C-Train Siemens-Duewag SD160".

- "C-Train Siemens-Duewag SD160".

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 27, 2018. Retrieved April 26, 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Markusoff, Jason (September 11, 2013). "Calgary Transit to buy 63 new LRT cars for $200M". Calgary Herald. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- Calgary Transit unveils first Siemens S200 LRV International Railway Journal January 18, 2016

- "New Mask CTrain car arrives". Calgary Transit. City of Calgary. January 14, 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- "Calgary's very first CTrain car retires after 2.5 million km career".

- "Ride the Wind". Calgary Transit. March 3, 2011. Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- Cuthbertson, Richard (February 17, 2011). "City wants electric car test". Calgary Herald. Postmedia Network. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- Logan, Shawn (February 19, 2009). "C-Train's the rail thing for one-billionth rider". The Calgary Sun. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- "CTrain Carries its One Billionth Customer" (Press release). City of Calgary. February 18, 2009. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- Calgary's Light Rail Transit Line (Calgary Transit page)

- 7 Avenue calary.ca Archived December 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- calgary.ca

- "Closure of 10 Street west downtown station" (PDF). The City of Calgary (website). Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- Calgary Transportation Infrastructure (2007). "7 Avenue Refurbishment". City of Calgary. Archived from the original on August 24, 2007. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- West LRT Opening Event Archived November 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "10 Street CTrain Station Closure". Archived from the original on September 4, 2012. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- "7 AVENUE REFURBISHMENT PROJECT UPDATE: DOWNTOWN WEST-KERBY STATION" (PDF). The City of Calgary (website). Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- Transit Corridor Renewal (World Buildings Directory) Archived February 9, 2013, at Archive.today

- World Architecture Festival Website

- Calgary Transit (2008). "Calgary LRT Network Plan" (PDF). City of Calgary: 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 29, 2009. Retrieved January 1, 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Calgary Transportation Infrastructure (2007). "Northwest LRT Extension – Dalhousie CTrain Station to Crowfoot CTrain Station". City of Calgary. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- Calgary City Council (2007). "Minutes of Calgary City Council special meeting of 06 November 2007" (MS Word). City of Calgary. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- "Northwest LRT Extension to Rocky Ridge/Tuscany". City of Calgary (website). Archived from the original on August 24, 2012. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- Calgary Transportation Planning (November 20, 2007). "2007 West LRT Report" (PDF). City of Calgary. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 11, 2008. Retrieved December 22, 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Saddletowne and Martindale Rider's Guide Archived August 31, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Calgary Transit (2008). "Calgary LRT Network Plan" (PDF). City of Calgary: 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 29, 2009. Retrieved January 1, 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Calgary Transportation Department (1983). "West LRT Functional Study" (PDF). City of Calgary. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 11, 2008. Retrieved December 22, 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "West LRT Project Booklet" (PDF). City of Calgary. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 4, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2012.

- "West LRT line will open December 10, 2012 on schedule, city says". Calgary Herald. November 7, 2012. Archived from the original on December 8, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- CBC Calgary (November 20, 2007). "Council confirms route for C-Train's west line". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- "West LRT (City of Calgary website)". City of Calgary. Archived from the original on April 10, 2013. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- West LRT Map (PDF) (Map) (2007 ed.). City of Calgary. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 11, 2008. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- Guttormson, Kim (October 5, 2009). "West LRT leg headed below ground after council vote". Calgary Herald. Global Calgary. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- Calgary Transit (2008). "West LRT – Route Map". City of Calgary. Archived from the original (Flash) on October 5, 2008. Retrieved 2009-06-13. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Calgary's West LRT project $35M over budget". CBC News. May 16, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- Cuthbertson, Richard (November 16, 2011). "Soaring west LRT costs hit $1.46B — and threatening to keep rising". Calgary Herald. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- Cuthbertson, Richard (January 2, 2012). "Nenshi fears rising cost of land acquisition for west LRT". Calgary Herald. Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- Markusoff, Jason (May 12, 2012). "Public art, land costs strain west LRT tab (Likely to eat into funds earmarked for southeast transit)". Calgary Herald. Archived from the original on May 15, 2012. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- "Calgary city council commits to art along west LRT line". CBC News. May 28, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- Markusoff, Jason (May 28, 2012). "City finds money from other projects to pay for west LRT public art". Calgary Herald. Archived from the original on June 1, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- Mayor Bronconnier Announces Design-Build Award, City of Calgary, October 29, 2009, archived from the original on October 5, 2008, retrieved June 9, 2010

- "Trains being tested on West LRT line". CBC News. May 15, 2012. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- "Test trains hit the tracks". CTV Calgary. May 15, 2012. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- Markusoff, Jason (May 15, 2012). "Test train begins rolling on $1.4-billion west LRT line (New line expected to open by March 2013)". Calgary Herald. Archived from the original on May 17, 2012. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- Ramsey, Melissa (May 15, 2012). "City tests first train on West LRT tracks". Global Calgary. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- "West LRT One Year Review" (pdf). 2014. p. 23. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- "RouteAhead: A Strategic Plan for Transit in Calgary". RouteAhead Planning Committee. Calgary Transit. December 7, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- Markusoff, Jason (December 7, 2012). "Calgary Transit releases RouteAhead plan". Calgary Herald. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- RouteAhead Section 4; Page 53 Archived December 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Markusoff, Jason (October 1, 2012). "Airport link moves up on list of transit's 30-year priorities". Calgary Herald. Archived from the original on September 24, 2012. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- Zickefoose, Sherri (October 1, 2012). "Calgary Transit presents council with $8-billion blueprint for future". Calgary Herald. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- Calgary Transit: Southeast Transitway (SETWAY) Archived February 10, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Green Line". City of Calgary. August 28, 2015. Retrieved May 2, 2016.