Caerphilly

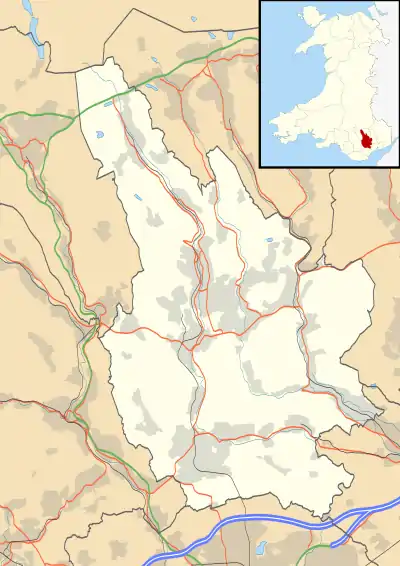

Caerphilly (/kaɪərˈfɪli/; Welsh: Caerffili, Welsh pronunciation: [ˌkɑːirˈfɪlɪ]) is a town and community in South Wales, at the southern end of the Rhymney Valley. It is the largest town in Caerphilly County Borough, within the historic borders of Glamorgan, on the border with Monmouthshire. At the 2011 Census, the town had a population of 41,402[1] while the wider Caerphilly Local Authority area has a population of 178,806.[2]

Caerphilly

| |

|---|---|

Caerphilly town and castle | |

Caerphilly Location within Caerphilly | |

| Population | 41,402 (2011 census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | ST1586 |

| Principal area | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Country | Wales |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | CAERPHILLY |

| Postcode district | CF83 |

| Dialling code | 029 |

| Police | Gwent |

| Fire | South Wales |

| Ambulance | Welsh |

| UK Parliament | |

| Senedd Cymru – Welsh Parliament | |

It is a commuter town for Cardiff and Newport, 7.5 miles (12 km) and 12 miles (19 km) away respectively, and is separated from the Cardiff suburbs of Lisvane and Rhiwbina by Caerphilly mountain. The town is perhaps best known outside of Wales for Caerphilly cheese.

History

The town's site has long been of strategic significance. Around AD 75 a fort was built by the Romans during their conquest of Britain.[3] An excavation of the site in 1963 showed that the fort was occupied by Roman forces until the middle of the 2nd century.[3]

Tradition states that a monastery was built in the area by St Cenydd, but this claim lacks support.[4] Nonetheless, the district was formerly named Senghenydd after him, and Cenydd's son, St Ffili, is said to have built a fort (Welsh: caer) in the area and thus gave the town its name.[5] Another explanation is that it is named after the Anglo-Norman Marcher Lord, Philip de Braose.[5]

Following the Norman invasion of Wales in the late 11th century, the area of Sengenhydd remained in Welsh hands. By the middle of the 12th century the area was under the control of the Welsh chieftain Ifor Bach (Ifor ap Meurig). His grandson Gruffydd ap Rhys was the final Welsh lord of Sengenhydd, falling to the English nobleman Gilbert de Clare, the Red Earl, in 1266.[4] In 1267 Henry III was forced to recognise Llywelyn ap Gruffudd as Prince of Wales, and by September 1268 Llywelyn had secured northern Sengenhydd. Gilbert de Clare had already begun to take steps to consolidate his own territorial gains, beginning the construction of Caerphilly Castle on 11 April 1268.[6] The castle would also act as a buffer against Llewelyn's own territorial ambitions and was attacked by the Prince of Wales' forces before construction was halted in 1270. Construction recommenced in 1271 and was continued under the Red Earl's son, Gilbert de Clare, 8th Earl of Gloucester.[7][8] With only interior remodelling carried out to the castle by Hugh le Despenser in the 1320s, Caerphilly Castle remains a pure example of 13th century military architecture and is the largest castle in Wales, and the second largest in Britain (after Windsor).[7][9]

The original town of Caerphilly grew up as a small settlement raised just south of the castle by De Clare.

After the death of Gilbert de Clare at the battle of Bannockburn in 1314, Edward II became guardian of De Clare's three sisters and heiresses. In 1315 he replaced de Badlesmere with a new English administrator, Payn de Turberville of Coity, who persecuted the people of Glamorgan. Then like many in northern Europe at the time, the region was in the throes of a serious famine. In coming to the defence of his people, Llywelyn Bren, the great grandson of Ifor Bach and Welsh Lord of Senghenydd incurred the wrath of de Turberville, who charged him with sedition. Llywelyn appealed to Edward II to call off or control his self-interested agent, but Edward ordered Llywelyn to appear before Parliament to face the charge of treason. The King promised Llywelyn that if the charges were found true, he would be hanged. Llywelyn fled and prepared for war. On 28 January 1316, Llywelyn began the revolt by a surprise attack on Caerphilly Castle. He captured the constable outside the castle and the outer ward but could not break into the inner defences. They burned the town, slaughtered some of its inhabitants and started a siege. The town was rebuilt but remained very small throughout the Middle Ages.[10] The first evidence of its emerging importance was the construction of a court house in the 14th century, the only pre-19th century building remaining in the town.

At the beginning of the 15th century the castle was again attacked, this time by Owain Glyndŵr, who took control of the castle around 1403–05. Repairs to the castle continued until at least 1430, but just a century later the antiquary John Leland recorded that the castle was a ruin set in marshland, with a single tower being used as a prison.[11][12] In the mid-16th century the 2nd Earl of Pembroke used the castle as a manorial court, but in 1583 the castle was leased to Thomas Lewis, who accelerated the castle's dilapidation by removing stonework to build his nearby manor, The Van.[7][12] The Lewis family, who claimed descent from Ifor Bach, left the manor in the mid-18th century when they purchased St Fagans Castle, The Van falling into decay.[8][11]

During the 1700s, Caerphilly began to grow into a market town, and during the 19th century, as the South Wales valleys underwent massive growth through industrialisation, so too the town's population grew. Caerphilly railway station was opened in 1871, and in 1899 the Rhymney Railway built their Caerphilly railway works maintenance facilities; however, the expansion of the population in the 19th century was more to do with the increasing market for coal.

Culture

Caerphilly is featured in the Sex Pistols documentary The Filth and the Fury. Protests and a prayer meeting were held outside the Castle Cinema on the evening of 14 December 1976, when the Pistols were playing a concert there. However, at this point in time, Caerphilly was one of the few councils that would allow the group to perform (Leeds and Manchester being the others). The castle of Caerphilly was used as a filming location for Merlin and the Doctor Who episodes The Rebel Flesh and The Almost People (2011).

Caerphilly hosted the National Eisteddfod in 1950.

There are a number of notable figures who grew up in Caerphilly. These include comedian Tommy Cooper, Newport County midfielder David Pipe, Juventus and Arsenal midfielder Aaron Ramsey, as well as Cardiff City F. C. and Wales footballer Robert Earnshaw, whose family relocated to the town from Zambia.

The town has a rugby union club, Caerphilly RFC, who play in Division Two East of the Welsh National League.

The town has hosted two food fairs, the Caerphilly Food Festival, which is held on the streets of the town, and the Big Cheese Festival, which has been held in and around Caerphilly Castle every summer since 1998. Visitor numbers reached 80,000 in 2012.[13] The event includes a wide variety of cheese stalls as well as a funfair, fireworks[14] and a cheese race around the castle.[15]

It hosts a fundraising musical event called Megaday.[16] In the Winter there is also the Festival of Light, which involves the procession of hundreds of lanterns through the centre of the town.

In 2012 Caerphilly County's only art gallery, Y Galeri, opened in St Fagan's Street in the town centre. It was part of plans to build a wider Arts Centre with exhibitions, workshops and talks.[17]

Caerphilly is home to two of major Welsh agricultural shows. Machen Agricultural Show is usually held on the first Saturday of July, and Bedwellty Agricultural Show, which is now held at the prestigious grounds of Llancaiach Fawr Manor, during August. Both events showcase the agricultural heritage of the county.

Caerphilly Heart Disease Study

The Caerphilly Heart Disease Study (also known as the Caerphilly Prospective Study) is one of the world's longest running epidemiology studies. Since 1979, a representative sample of adult males born between 1918 and 1938, living in Caerphilly and the surrounding villages of Abertridwr, Bedwas, Machen, Senghenydd and Trethomas, have participated in the study. A wide range of health and lifestyle data have been collected throughout the study and have been the basis for over 400 publications in the medical press. A notable report was on the reductions in vascular disease, diabetes, cognitive impairment and dementia attributable to a healthy lifestyle.[18]

Transport

Aviation

The nearest airport is Cardiff which is just under 20 kilometres (12 mi) away.

Rhoose Cardiff International Airport railway station is 59 minutes from Caerphilly by public transport (there is a daily direct rail service to the airport each morning). It is a 35-minute drive from the town.

Rail

Caerphilly has three railway stations. All are located on the Rhymney Line serving Cardiff.

- Caerphilly at the southern end of the town near the shopping area

- Aber in the western part of the town

- Energlyn & Churchill Park railway station in the far western part of the town

The rail service between Caerphilly and Cardiff Queen Street typically takes 13 minutes. From there services continue to Penarth, Cardiff Central, or on occasion Bridgend.

Road

The A469 trunk road runs through the town north to south, while the A468 skirts the northern boundary of the town.

Traditional buses

Caerphilly Urban District Council (UDC) had its own fleet of buses, which began operating in 1920 although powers to operate them had been obtained by the UDC in 1917. In 1974, this fleet was amalgamated with those of Bedwas and Machen UDC and of Gelligaer UDC to create the bus fleet of Rhymney Valley District Council.[19] The fleet persists today as a heritage operation.[20]

Notable people

- See also Category:People from Caerphilly

- The pop-punk band Attack! Attack! were formed in Caerphilly.

- Norrie Alden, footballer

- Donald Braithwaite (1936–2017), Former professional boxer, Bronze medalist at the 1958 British Empire and Commonwealth Games

- Margaret Bevan (born c.1894), girl evangelist

- Manon Carpenter (born 1993), Mountain bike World Champion

- Tommy Cooper (1921–1984), comedian and magician. There is a statue commemorating him in the Twyn area.

- Daniel and Laura Curtis, Composers

- Amy Dowden (born 1991), professional dancer on BBC programme Strictly Come Dancing

- Sian Evans (born 1971), Singer-songwriter of the band Kosheen

- Matt Johnson (born 1982), TV presenter

- Aaron Ramsey (born 1990), Wales and Juventus Midfielder

- Craig Roberts (born 1991), actor and director from Maesycwmmer, Caerphilly

- Eirlys Roberts (1911–2008), consumer advocate and campaigner[21]

- Malcolm Uphill (1935–1999), professional motorcycle racer

- Leona Vaughan (born 1995), actress from Caerphilly

- Sam Fenwick (born 1992), squash player from Caerphilly

References

- UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Caerphilly Built-up area sub division (W38000086)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Caerphilly Local Authority (W06000018)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- "Roman Auxiliary Fort, Caerphilly, Mid Glamorgan". roman-britain.org. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- Evans 1948, p. 210.

- Morgan, Thomas (1912). The Place-names of Wales. Newport, Monmouthshire: JE Southall. p. 168.

- Newman 1995, p. 167.

- "Caerphilly Castle". castlewales.com. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- Davies et al. 2008, p. 106.

- "Caerphilly Castle". BBC. 24 November 2010. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- Newman 1995, p. 176.

- Evans 1948, p. 214.

- Newman 1995, p. 169.

- "Caerphilly's Big Cheese draws thousands to town". Campaign. Newport. 31 July 2013. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- "Ponty Big Weekend and Caerphilly Big Cheese". Wales Online. 26 July 2010. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- "Your guide to the Big Cheese 2012". Caerphilly Observer. 27 July 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- "Home". www.megaday.net.

- "New art gallery opens in Caerphilly". Caerphilly Observer. 29 May 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- "Caerphilly and Speedwell collaborative heart disease studies. The Caerphilly and Speedwell Collaborative Group". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 38 (3): 259–262. 1984. doi:10.1136/jech.38.3.259. PMC 1052363. PMID 6332166.

- Witton 1976, pp. 28–29.

- "Welsh Transport Heritage :: Rhymney Valley Transport Preservation Society". welsh-transport-heritage.co.uk.

- "Eirlys Roberts". Telegraph. 21 March 2008. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

Bibliography

- Davies, John; Jenkins, Nigel; Menna, Baines; Lynch, Peredur I., eds. (2008). The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-1953-6.

- Evans, C.J.O. (1948). Glamorgan, its History and Topography. Cardiff: William Lewis.

- Newman, John (1995). Glamorgan. London: Penguin Group. ISBN 0-14-071056-6.

- Witton, Alan M., ed. (September 1976). Fleetbook 9: Buses of South Wales. Manchester: A.M. Witton. ISBN 0-86047-091-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Caerphilly (town). |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Caerphilly. |

Caerphilly travel guide from Wikivoyage

Caerphilly travel guide from Wikivoyage- The Caerphilly Woodlands Trust

- Geograph- Photos of Caerphilly and surrounding area

- Caerphilly Observer Local news website