Castile and León

Castile and León (UK: /kæˈstiːl ... leɪˈɒn/, US: /-ˈoʊn/; Spanish: Castilla y León [kasˈtiʎa i leˈon] (![]() listen))[n. 1] is an autonomous community in north-western Spain.

listen))[n. 1] is an autonomous community in north-western Spain.

Castile and León

| |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) Location of Castile and León within Spain | |

| Coordinates: 41°23′N 4°27′W | |

| Country | Spain |

| Capital | de facto Valladolid |

| Provinces | Ávila, Burgos, León, Palencia, Salamanca, Segovia, Soria, Valladolid and Zamora |

| Government | |

| • President | Alfonso Fernández Mañueco (PP) |

| • Legislature | Cortes of Castile and León |

| • Executive | Junta of Castile and León |

| Area | |

| • Total | 94,222 km2 (36,379 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 1st (18.6% of Spain) |

| Population (2016) | |

| • Total | 2,447,519 |

| • Density | 26/km2 (67/sq mi) |

| • Pop. rank | 6th |

| • Percent | 5.42% of Spain |

| Demonyms | Castilian, Leoneses (according region) |

| GDP (nominal; 2018) | |

| • Per capita | €24,397 |

| ISO 3166 code | ES-CL |

| Official languages | Castilian |

| Statute of Autonomy | March 2, 1983 |

| Congress seats | 31 (of 350) |

| Senate seats | 39 (of 265) |

| HDI (2017) | 0.888[2] very high · 7th |

| Website | Junta de Castilla y León |

It was created in 1983. Formed by the provinces of Ávila, Burgos, León, Palencia, Salamanca, Segovia, Soria, Valladolid and Zamora, it is the largest autonomous community in Spain in terms of area, covering 94,222 km2. It is however sparsely populated, with a population density below 30/km2. While a capital has not been explicitly declared, the seats of the executive and legislative powers are set in Valladolid by law and for all purposes that city (also the most populated municipality) serves as de facto regional capital.

Castile and León is a landlocked region, bordered by Portugal as well as by the Spanish autonomous communities of Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, the Basque Country, La Rioja, Aragon, Castilla–La Mancha, the Community of Madrid and Extremadura. Chiefly comprising the northern half of the Inner Plateau, it is surrounded by mountain barriers (the Picos de Europa to the North, the Sistema Central to the South and the Sistema Ibérico to the East) and it is drained by the Douro River, flowing west toward the Atlantic Ocean.

The region contains eight World Heritage Sites. UNESCO recognizes the Cortes of León of 1188 as the cradle of worldwide parliamentarism.[3]

Symbols

The Statute of Autonomy of Castile and León, reformed for the last time in 2007, establishes in the sixth article of its preliminary title the symbols of the community's exclusive identity. These are: the coat of arms, the flag, the banner and the anthem. Its legal protection is the same as that corresponding to the symbols of the State -whose outrages are classified as crime in article 543 of the Penal Code-.[4]

In the articulated statuary, the coat of arms is defined as follows:[4]

The coat of arms of Castile and León is a stamped shield by open royal crown, barracked in cross. The first and fourth quartering: in the field of gules, a merloned golden castle of three merlons, drafted of sable and rinse of azure. The second and third quartering: in a silver field, a rampant lion of purple, lingued, dyed and armed with gules, crowned with gold.

Likewise, the flag is described as follows:[4]

The flag of Castile and León is quartered and contains the symbols of Castile and León, as described in the previous section. The flag will fly in all the centres and official acts of the Community, to the right of the Spanish flag.

Following the same wording, the banner is constituted by the shield quartered on a traditional crimson background. The Statute also expresses: "The anthem and the other symbols [...] will be regulated by specific law". After the promulgation of the fundamental norm, this law was not promulgated, so the anthem does not exist, but de iure is a symbol of autonomy.[4]

History

Several archaeological findings show that in prehistoric times these lands were already inhabited. In the Atapuerca Mountains have been found many bones of the ancestors of Homo sapiens, making these findings one of the most important to determine the history of human evolution. The most important discovery that catapulted the site to international fame was the remains of Homo heidelbergensis.

Before the arrival of the Romans, it is known that the territories that make up Castile and León today were occupied by various Celtic peoples, such as vaccaei, autrigones, turmodigi, the vettones, astures or celtiberians. The Roman conquest resulted in warring with the local tribes. One particularly famous episode was the siege of Numantia, an old town located near the current city of Soria.

The romanization was unstoppable, and to this day great Roman works of art have remained, mainly the Aqueduct of Segovia as well as many archaeological remains such as those of the ancient Clunia, Salt mines of Poza de la Sal and the vía de la Plata pathway, which crosses the west of the community from Astorga (Asturica Augusta) to the capital of modern Extremadura, Mérida (Emerita Augusta).

With the fall of Rome, the lands were occupied militarily by the Visigoth peoples of Germanic origin. The subsequent arrival of the Arabs was followed by a process known as the Reconquista. In the mountainous area of Asturias, a small Christian kingdom was created which opposed the Islamic presence in the Peninsula. They proclaimed themselves heirs of the last Visigoth kings, who in turn had been deeply romanized. This resistance of Visigoth-Roman heritage and supported by Christianity, was becoming increasingly strong and expanding to the south, eventually setting its court in the city of León, becoming the Kingdom of León. To favor the repopulation of the new reconquered lands, a number of fueros or letters of repopulation were granted by the monarchs.

In the Middle Ages the pilgrimage by Christianity to Santiago de Compostela was popularized. The Camino de Santiago runs along the northern part of the region, and contributed to the spread of European cultural innovations throughout the peninsula. Today the Camino is still an important touristic and cultural attraction.

In 1188, the basilica of San Isidoro of León was the setting of the first parliamentary body in the history of Europe, with the participation of the Third Estate. The king who summoned it was Alfonso IX of León.

The legal basis for the kingdom was the Roman law, and because of this the kings increasingly wanted more power, like the Roman emperors. This is very clearly seen in the Siete Partidas of Alfonso X of Castile, which shows the imperial monism that the king sought. The King did not want to be a primus inter pares, but the source of the law.

Simultaneously, a county of this Christian kingdom of León, began to acquire autonomy and to expand. This is the primitive County of Castile, which would grow into a powerful kingdom among the Christian kingdoms of the Peninsula. The first Castilian count was Fernán González.

León and Castile continued to expand to the South, even beyond the Douro river, seeking to conquest lands under Islamic rule. That was the time of the Cantares de gesta, poems which recount the great deeds of the Christian nobles who fought against the Muslim enemy. Despite this, Christian and Muslim kings maintained diplomatic relations. One clear example is Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, El Cid, paradigm of the medieval Christian knight, who fought both for Christian and Muslim kings.

The origin of the definitive dynastic unification of the kingdoms of Castile and León, which had been separated for just seven decades, was in 1194. Alfonso VIII of Castile and Alfonso IX of León signed in Tordehumos the treaty that pacified the area of Tierra de Campos and laid the foundation for a future reunification of the kingdoms, consolidated in 1230 with Ferdinand III the Saint. This agreement is called the Treaty of Tordehumos.

.jpg.webp)

During the Late Middle Ages there was an economic and political crisis produced by a series of bad harvests and by disputes between nobles and the Crown for power, as well as between different contenders for the throne. In the Cortes of Valladolid of 1295, Ferdinand IV is recognized as king. The painting María de Molina presents her son Fernando IV in the Cortes of Valladolid of 1295 presides today the Spanish Congress of Deputies along with a painting of the Cortes of Cádiz, emphasizing the parliamentarian importance that has all the development of Cortes in Castile and León, despite its subsequent decline. The Crown was becoming more authoritarian and the nobility more dependent on it.

The reconquista continued advancing in this thriving Crown of Castile, and culminated with the surrender of the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada, last Muslim stronghold in the Peninsula, in 1492.

Antecedents of the autonomy

In June 1978, Castile and León obtained the pre-autonomy, through the creation of General council of Castile and León by Royal Decree-Law 20/1978, of June 13.

In times of the First Spanish Republic (1873-1874), the federal republicans conceived the project to create an federated state of eleven provinces in the valley of the Spanish Douro, that would also have included the provinces of Santander and Logroño. Very few years before, in 1869, as part of a manifesto, federal republicans representatives of the 17 provinces of Albacete, Ávila, Burgos, Ciudad Real, Cuenca, Guadalajara, León, Logroño, Madrid, Palencia, Salamanca, Santander, Segovia, Soria, Toledo, Valladolid and Zamora proposed in the so-called Castilian Federal Pact the conformation of an entity formed by two different "states": the state of Old Castile -that is presently built for the current Castilian-Leonese provinces and the provinces of Logroño and Santander-, and the state of New Castile -which conforms to the current provinces of Castile-La Mancha plus the province of Madrid-. The end of the Republic, at the beginning of 1874, thwarted the initiative.

In 1921, on the occasion of the fourth centenary of the Battle of Villalar, the Santander City Council advocated the creation of a Castilian and Leonese Commonwealth of eleven provinces, idea that would be maintained in later years. At the end of 1931 and beginning of 1932, from León, Eugenio Merino elaborated a text in which the base of a Castilian-Leonese regionalism was put. The text was published in the Diario de León newspaper.[8]

During the Second Spanish Republic, especially in 1936, there was a great regionalist activity favorable to a region of eleven provinces, and even bases for the Statute of Autonomy were elaborated. The Diario de León advocated for the formalization of this initiative and the constitution of an autonomous region with these words:

Join in a personality León and Old Castile around the great basin of the Douro, without to fall now into provincial rivalries.

— Diario de León, May 22, 1936.

The end of the Spanish Civil War and the beginning of Franco regime ended the aspirations of the autonomy for the region. The philosopher José Ortega y Gasset collected this scheme in his publications.[9]

After the death of Francisco Franco, regionalist, autonomist and nationalist organizations (Castilian-Leonese regionalism and Castilian nationalism) as Regional Alliance of Castile and León (1975), Regional Institute of Castile and León (1976) or the Autonomous Nationalist Party of Castile and León (1977). Later after the extinction of these formations arose in 1993 Regionalist Unity of Castile and León.[10]

At the same time, others of Leonesist character arose, such as the Leonese Autonomous Group (1978) or Regionalist Party of the Leonese Country (1980), which advocated the creation of a Leonese autonomous community, composed of provinces of León, Salamanca and Zamora. The popular and political support that maintained the uniprovincial autonomy in León became very important in that city.

Autonomy

The autonomous community of Castile and León is the result of the union in 1983 of nine provinces: the three that, after the territorial division of 1833, by which the provinces were created, were ascribed to the Region of León, and six ascribed to Old Castile; however 2 provinces of Old Castile were not included: Santander (current community of Cantabria) and Logroño (current La Rioja).

In the case of Cantabria the creation of an autonomous community was advocated for historical, cultural and geographical reasons, while in La Rioja the process was more complex due to the existence of three alternatives, all based on historical and socio-economic reasons: union with Castile and León (advocated by the Union of the Democratic Centre political party), union to a Basque-Navarrese community (supported by the Socialist Party and Communist Party) or creation of an uniprovincial autonomy; the latter option was chosen because it had more support among the population.

After the creation of the Castilian-Leonese pre-autonomous body, which was supported by the Provincial Council of León in its agreement of April 16, 1980, this institution revoked its original agreement on January 13, 1983, just as the draft of the Organic Law entered the Spanish parliament. The Constitutional Court determined which of those contradictory agreements was valid in the Sentence 89/1984 of September 28; it declares that the subject of the process is no longer, as in its preliminary phase, the councils and municipalities, but the new body.

After the sentence, there were several demonstrations in León in favor of the León alone option, one of them according to some sources brought together a number close to 90 000 people,[11] This was the highest concentration held in the city in the Democratic period until the demonstrations rejecting the 2004 Madrid train bombings.[12]

In an agreement adopted on July 31, 1981, the Provincial Council of Segovia decided to exercise the initiative so that Segovia could be constituted as a uniprovincial autonomous community, but in the municipalities of the province the situation was equal between the supporters of the uniprovincial autonomy and the supporters of the union.

The City Council of Cuéllar initially adhered to this autonomic initiative in agreement adopted by the corporation on October 5, 1981. However, another agreement adopted by the same corporation dated December 3 of the same year revoked the previous one and the process was paralyzed pending the processing of an appeal filed by the provincial council against this last agreement; this change of opinion of the city council of Cuéllar tipped the scales in the province towards the autonomy with the rest of Castile and León, but it was an agreement that arrived out of time. Finally the province of Segovia was incorporated into Castile and León along with the other eight provinces and legal coverage was given through the Organic Law 5/1983 for "reasons of national interest", as provided for in article 144 c of the Spanish Constitution for those provinces that have not exercised their right on time.

Today, the Villalar Foundation is responsible for cultural activities on the art, culture or identity of Castile and León.[13]

The community grants each year, on the Castile and León Day, the Castile and León Awards to the Castilian-Leonese persons outstanding in the following areas: arts, human values, scientific research, social sciences, restoration and conservation, environment and sports.[14]

Geography

Location

Castile and León is an autonomous community with no exit to the sea that is located in the north-western quadrant of the Iberian Peninsula. Its territory borders on the north with the uniprovincial communities of the Principality of Asturias and Cantabria as well as with the Basque Country (Biscay and Álava); to the east with the uniprovincial community of La Rioja and with Aragon (province of Zaragoza), to the south with the Community of Madrid, Castile-La Mancha (provinces of Toledo and Guadalajara) and Extremadura (province of Cáceres) and to the west with Galicia (provinces of Lugo and Ourense) and Portugal (Bragança District and Guarda District).

Orography

The morphology of Castile and León is formed, for the most part, by the Meseta and a belt of mountainous reliefs. The plateau is a high plateau, which has an average altitude close to 800 metres (2,600 ft) above sea-level, is covered by deposited clay materials that have given rise to a dry and arid landscape.

Following the morphology of the area can be seen: to the north, the mountains of the provinces of Palencia and of León with high and spiky summits and the mountains of province of Burgos, divided into two parts by the Pancorbo gorge, link between the Basque Country and Castile. Of these, the northern part belongs to the Cantabrian Mountains and reaches the city of Burgos. The east-southeast zone, belonging to the Sistema Ibérico. In the northwest part the mountains of Zamora extend, with peaks reduced to plateaux by erosion. To the east, in the Soria mountains, you can see the Sistema Ibérico, presided over by the Moncayo Massif, its highest peak. Separating the northern plateau from the southern, to the south, the Sistema Central rises, where the mountain ranges of Gata, Francia, Béjar and Gredos in the western half and those of Ávila, Guadarrama, Somosierra and Ayllón in the eastern half.

Geology

The Northern Plateau (Meseta Norte) is constituted by Paleozoic sockets. At the beginning of the Mesozoic Era, once the Hercynian folding that raised the current Central Europe and the Gallaeci zone of Spain, the deposited materials were dragged by the erosive action of the rivers.

During the alpine orogeny, the materials that formed the plateau broke through multiple points. From this fracture rose the mountains of León, with mountains of not much height and, constituting the spine of the Plateau (Meseta), the Cantabrian Mountains and the Sistema Central, formed by materials such as granite or metamorphic slates.

The karst complex of Ojo Guareña, consisting of 110 km of galleries[15] and its caves formed in carbonatic materials of Coniacian which are situated on a level of impermeable marls, is the second largest of the peninsula.

This geological configuration has allowed upwellings of mineral-medicinal or thermal water, used now or in the past, in Almeida de Sayago, Boñar, Calabor, Caldas de Luna, Castromonte, Cucho, Gejuelo del Barro, Morales de Campos, Valdelateja and Villarijo, among other places.

Rivers

- Douro basin

The main hydrographic network of Castile and León is constituted by the Douro river and its tributaries. From its source in the Picos de Urbión, in Soria, to its mouth in the Portuguese city of Porto, the Douro covers 897 km. From the north descend the Pisuerga, the Valderaduey and the Esla rivers, its tributaries more plentiful and by the east, with less water in its flows, highlight the Adaja and the Duratón. After passing the town of Zamora, the Douro is confined between the canyons of the Arribes del Duero Natural Park, bordering with Portugal. On the left bank are important tributaries such as Tormes, Huebra, Águeda, Côa and Paiva, all from Sistema Central. On the right they reach the Sabor, the Tua and the Tâmega, born in the Galician Massif. After the Arribes area, the Douro turns west into Portugal until it empties into the Atlantic Ocean.

- Other watersheds

Several rivers of the community pour their waters into the Ebro basin, in Palencia, Burgos and Soria (Jalón river), that of Miño-Sil in León and Zamora, that of the Tagus in Ávila and Salamanca (rivers Tiétar and Alberche and Alagón respectively) and Cantabrian basin in the provinces through which the Cantabrian Mountains extends.

- Rivers and provincial capitals where they pass

| River | Capital | River mouth | Other locations where it passes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adaja | Ávila | Douro in Villamarciel | Tordesillas and Arévalo |

| Arlanzón | Burgos | Arlanza in Quintana del Puente | Arlanzón and Pampliega |

| Bernesga | León | Esla | La Robla |

| Carrión | Palencia | Pisuerga in Dueñas | Guardo and Carrión de los Condes |

| Tormes | Salamanca | Douro in Fermoselle | El Barco de Ávila, Guijuelo, Alba de Tormes and Ledesma |

| Eresma | Segovia | Adaja in Matapozuelos | Coca |

| Douro | Soria and Zamora | Atlantic Ocean in Porto | Almazán, Aranda de Duero, Tordesillas, Toro, Aldeadávila de la Ribera and Vilvestre |

| Pisuerga | Valladolid | Douro in Geria | Aguilar de Campoo, Cervera de Pisuerga, Venta de Baños, Dueñas, Tariego de Cerrato and Simancas |

Lakes and reservoirs

In addition to the rivers, the Douro basin also hosts a large number of lakes and lagoons such as the Negra de Urbión Lake, in the Picos de Urbión, the Grande de Gredos Lake , in Gredos, the Sanabria Lake, in Zamora or the La Nava de Fuentes Lake in Palencia. Also emphasize a great amount of reservoirs, fed by the water coming from the rains and the thaw of the snowy summits. Thus, Castile and León, despite not having abundant rainfall, is one of the communities in Spain with the highest level of water dammed.

Many of these natural lakes are being used as an economic resource, boosting rural tourism and helping to conserve ecosystems. The Sanabria Lake was a pioneer in this.

Climate

Castile and León has a Continental Mediterranean Climate, with long, cold winters, with average temperatures between 3 and 6 °C in January and short, hot summers (average 19 to 22 °C), but with the three or four months of summer aridity characteristic of the Mediterranean climate. Rainfall, with an average of 450–500 mm per year, is scarce, accentuating in the lower lands.

- Climatic factors

In Castile and León the cold extends almost continuously for much of the year, being a very characteristic element of its climate. The coldest periods of winter are associated with invasions of a continental polar front and strata of marine arctic air, rare is that they do not reach temperatures of the order of -5 ° to -10 °C. Likewise, in situations of anticyclone, in the interior of the region they cause persistent fogs, creating prolonged cold situations due to radiation processes. The intense "cold waves" of the winter central months are typical, showing a particular tendency to occur from the second fortnight of December to the first of February. During its course the most extreme minimum temperatures occur, whose values vary between -10 ° and -13 °C of its westernmost sector and -15 ° and -20 °C of the central plains and high moorlands. The lowest recorded records reach -22 °C of Burgos, -21.9 °C in Coca (Segovia), -20.4 °C in Ávila, -20 °C in Salamanca and -19.2 °C in Soria. The high altitude of the Meseta and its mountains accentuates the contrast between winter and summer temperatures, as well as day and night temperatures.[16]

Due to the mountainous barriers that surround Castile and León, the maritime winds are stopped, thus stopping the precipitations. Due to that, the rains fall in a very unequal way in the Castilian and Leonese territory. While in the middle of the Douro basin there is an annual average of 450 mm, in the western regions of the mountains of León, the Cantabrian Mountains and the southern area of the Provinces of Ávila and Salamanca, rainfall reaches 1500 mm per year, with a maximum of 3400 mm per year in the western part of the Sierra de Gredos, in the Candelario-Bejar Massif, which makes this area the rainiest not only from Spain, but from the Iberian Peninsula.[17]

- Climatic regions

.jpg.webp)

Although Castile and León is framed within the continental climate, in its lands different climate domains are distinguished:[18]

- According to the Köppen climate classification, a large part of the autonomous community falls within the Csb or Cfb variants, with the average of the warmest month below 22 °C but above 10 °C for five or more months.

- In several areas of the Meseta Central the climate is classified as Csa (warm Mediterranean), by exceeding 22 °C during the summer.

- In high elevations of the Cantabrian Mountains and mountain areas, there is a cold temperate climate with average temperatures under 3 °C in the coldest months and dry summers (Dsb or Dsc).

Flora

._Parque_Nacional_Picos_de_Europa._ES000003._ROSUROB.JPG.webp)

Castile and León has many protected natural sites. Actively collaborates with the European Union program Natura 2000. There are also some special protection area for birds or SPA. The solitary evergreen oaks and junipers (Juniperus sect. Sabina) that now draw the Castilian-Leonese plain are remnants of the forests that covered these same lands long ago. The agricultural holdings, due to the need of land for the cultivation of cereal and pastures for the immense herds of the Castilian Plateau, supposed the deforestation of these lands during the Middle Ages. The last Castilian and Leonese forests of junipers are found in the Provinces of León, Soria and Burgos. They are not very leafy forests that can form mixed communities with evergreen oaks, Portuguese oaks or pines.

The Castilian-Leonese slope of the Cantabrian Mountains and the northern foothills of the Sistema Ibérico have a rich vegetation. The most humid and fresh slopes are populated by large beeches, whose extension areas can reach 1,500 m altitude. In turn, the European beech forms mixed forests with the yew, the sorbus, the whitebeam, the European holly and the birch. On the sunny slopes the sessile oak, the European oak, the ash, the lime tree, the sweet chestnut, the birch and the scots pine (a typical species from the north of the Province of León).

On the lower slopes of the Sistema Central extensive extensions of holm oaks survive. At a higher level, between 1000 and 1100 masl, chestnut trees abound. Above them predominates the pyrenean oak, very resistant to the cold, whose stratum extends until the 1700 masl. However, many oak groves have disappeared, cut down by man and replaced by pine trees of repopulation. The main native pine forests are found in the Sierra de Guadarrama. The subalpine zones located between 1700 and 2200 masl are home to thickets of cytisus oromediterraneus and junipers.

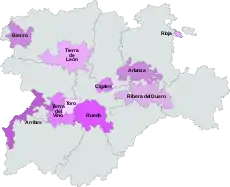

Much of the Province of Salamanca, especially in the districts of Campo Charro and Comarca de Ciudad Rodrigo, is occupied by dehesas, a type of forest similar to that of the African savannas, with evergreen oaks, cork oaks, quercus faginea and pyrenean oaks. The Province of Salamanca and that of Valladolid in the region of Rueda also has the only Castilian-Leonese olive groves, since these trees do not grow in any of the other regions of the community. Also noteworthy are the wine regions with very good quality wines such as those from Toro, those from Ribera del Duero (Valladolid, Burgos, Soria) those from Rueda, or those of Cigales.

Fauna

Castile and León presents a great diversity of fauna. There are numerous species and some of them are of special interest because of their uniqueness, such as some endemic species, or because of their scarcity, such as the brown bear. There have been counted 418 species of vertebrates, which make up 63% of all vertebrates that live in Spain. Animals adapted to life in the high mountains, inhabitants of rocky places, inhabitants of fluvial courses, species of plains and forest residents form the mosaic of the Castilian-Leonese fauna.

The isolation to which the high summits are subject leads to the existence of abundant endemisms such as the Spanish ibex, which in Gredos constitutes a unique subspecies in the Peninsula. The European snow vole is a graceful small mammal of grayish brown color and long tail that lives in open spaces over the limit of the trees.

Small and large mammals such as squirrel, dormouse, talpids, European pine marten, Beech marten, fox, wildcat, wolf, quite abundant in some areas, boar, deer, roe deer and, only in the Cantabrian Mountains, some specimens of brown bear tend to frequent the deciduous forests, although some species also extend to coniferous forests and scrubland. The wildcat is slightly larger than a domestic cat, has a short and stout tail, with dark rings and striped fur. The Iberian lynx, however, lives almost exclusively in areas of Mediterranean scrubland.

_02.jpg.webp)

Small reptiles such as the ladder snake, the coronella girondica and the aesculapian snake are also found in this environment. The smooth snake can be found from sea level to 1,800 m in height and in the community it tends to live on the heights. Further up, in the rocky areas of the subalpine floor at about 2,400 m altitude the Iberian rock lizard lives, one of the few reptiles adapted at this point.

In the mountain rivers live the otter and desman and in its waters the trout, anguillidae, the common minnows and some of the increasingly scarce autochthonous river crabs. The otter and the desman are two mammals with aquatic habits and very good swimmers. The otter feeds mainly on fish, while the desman seeks its food among the aquatic invertebrates that inhabit the riverbed. In lower sections of calmer waters swim barbel s and carps. Among the amphibians, the salamanders and as remarkable species: the Almanzor salamander (Salamandra salamandra almanzoris) and the Gredos toad (Bufo bufo gredosicola), which are two endemic subspecies to the Sistema Central.

Where the rivers are encased forming sickles and canyons, rock-dwelling birds such as griffon vulture, cinereous vulture, Egyptian vulture, golden eagle or peregrine falcon. The Egyptian vulture, a small vulture, is black and white with a yellow head. Downstream and on its banks between the lush vegetation form their colonies the black-crowned night heron and the grey heron and the goldcrest, the eurasian penduline tit, the eurasian hoopoe and the common kingfisher.

Among the birds that populate the open Mediterranean forests live two endangered species: the black stork and the Spanish imperial eagle. The black stork, much rarer than its congener the white stork, is of solitary habits and lives far from man. The Spanish imperial eagle nests in the trees and feeds mainly on rabbits, but also birds, reptiles and carrion.

In the coniferous forests live among others the short-toed treecreeper, the coal tit and the eurasian nuthatch, a bird of gray back and flanks reddish-orange that it nests in holes to which it narrows the entrance with mud. The western capercaillie is a very dark and large rooster that lives in forest environments, so it is very difficult to observe. Among the forest raptors are the accipiter, the eurasian sparrowhawk or the tawny owl, which frequently attack other smaller birds such as eurasian jay, european green woodpecker, fringilla, great spotted woodpecker and typical warbler.

The bustard frequents the open plains with rain-fed crops; It is large and has a grayish head and neck and a brown back. In the Castilian-Leonese wetlands during the winter many specimens of greylag goose, which breeds in northern Europe and visits the area in winter, are concentrated.

The naturalist Félix Rodríguez de la Fuente (1928 - 1980), natural from Poza de la Sal, stands out in the scientific study and its dissemination. He had a great research and made the leap to fame with the television series El hombre y la Tierra (TVE).

In the Montaña Palentina, in the municipality of San Cebrián de Mudá, a program of reintroduction of the European bison,[19] animal that had been a thousand years without presence in the Iberian Peninsula, in order to avoid the extinction of the species.

Demography

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 2,302,417 | — |

| 1910 | 2,362,878 | +2.6% |

| 1920 | 2,337,405 | −1.1% |

| 1930 | 2,477,324 | +6.0% |

| 1940 | 2,694,347 | +8.8% |

| 1950 | 2,864,378 | +6.3% |

| 1960 | 2,848,352 | −0.6% |

| 1970 | 2,623,196 | −7.9% |

| 1981 | 2,575,064 | −1.8% |

| 1991 | 2,562,979 | −0.5% |

| 2001 | 2,456,474 | −4.2% |

| 2011 | 2,540,188 | +3.4% |

| 2017 | 2,436,850 | −4.1% |

| Source: INE | ||

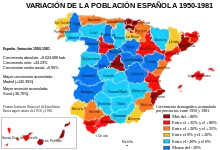

With 2 528 417 inhabitants (January 1, 2007), 1 251 082 men and 1 277 335 women, the population of Castile and León represents 5.69% of the population of Spain, although its vast territory covers almost a fifth of the total area of the country. In January 2005, the population of Castile and León was divided, by province, as follows: Province of Ávila, 168 638 inhabitants; Province of Burgos, 365 972; Province of León, 497 387; Province of Palencia, 173 281; Province of Salamanca, 351 326; Province of Segovia, 159 322; Province of Soria, 93 593; Province of Valladolid, 521 661; and Province of Zamora, 197 237.

The autonomous community has a very low population density, around 26.57 inhabitants/km2, a record that is more than three times lower than the national average, which indicates that it is a sparsely populated and demographically decline, especially in rural areas and even in small traditional cities. The demographic characteristics of the territory show an aging population, with a low birth rate and mortality that approaches the state average.

In the year 2000, the population of Castile and León totaled 2 479 118 people, that is, 6.12% of the Spanish total. Its natural growth was one of the lowest in Spain: -7223 (-2.92 gross rate), as a result of the difference between the 25 080 deaths (10.12 of the gross rate) and the 17 857 births ( 7.20 gross rate). The number of inhabitants in 1999 was slightly higher (2 488 062), so that, despite the negative growth, the relative numerical stability is partly due to the increase in immigration: of 22 910 immigrants in 1999 it went to 24 340 in 2000. In that year, 59 children under the age of one year died.

The life expectancy is higher than the Spanish average: 83.24 for women and 78.30 for men, a superiority that in 1999 was repeated in the register, since women added 1 260 906 and the males 1 227 156. A study by the University of Porto (Portugal) cites Castile and León as one of the European regions where old people could expect to live longer.[20]

In 1999, the age distribution gave the following results: 317 783 people from 0 to 14 years old; 913 618 between 15 and 39 years old; 576 183 from 40 to 59 years and 677 020 over 60 years.

The active population in 2001 was 1 005 200 and occupied 884 200 people, with which the unemployment was 12.1% of the active population. For sectors of the employed population, 10.9% worked in agriculture, 20.6% in the industry, 12.7% in construction, and 63,1 % in the services sector.

Historical evolution

Many of the people of the territory, who devoted themselves mostly to agriculture and livestock, gradually abandoned the area, heading towards urban areas, much more prosperous. This situation was further aggravated at the end of the Spanish Civil War, with a progressive rural emigration. During the 1960s and 1980s, large urban centers and provincial capitals suffered a slight demographic increase due to a thorough urbanization process, although, despite this, the Castilian-Leonese area continues to suffer serious depopulation. Only the Provinces of Burgos, Valladolid and Segovia are gaining population in recent years.

There is also an increase in the population of metropolitan areas around cities such as Valladolid, Burgos or León. Due to this phenomenon, cities such as Laguna de Duero or San Andrés del Rabanedo have seen their population increase rapidly in a few years. The metropolitan area of the city of Valladolid is, by far, the largest in the autonomous community, with more than 430 000 inhabitants.

However, in absolute terms the autonomous community is losing population and aging. In 2011, it was one of only four autonomous communities that lost population along with Asturias, Galicia and Aragon.

Present-day population distribution

In 1960 the urban population meant 20.6% of the total population of Castile and León; in 1991 this percentage had risen to 42.3% and in 1998 it was approaching 43%, which indicates the progressive state of rural depopulation.

The phenomenon is also reflected in the number of municipalities with less than 100 inhabitants, which was multiplied by seven between 1960 and 1986. Outside the provincial capitals, cities such as Miranda de Ebro and Aranda de Duero in Province of Burgos, Ponferrada and San Andrés del Rabanedo in Province of León, Béjar in Province of Salamanca and Medina del Campo and Laguna de Duero in Province of Valladolid.

Of the 2248 municipalities of this community, the 2014 registry registered 1986 with less than 1000 inhabitants; 204 from 1001 to 5000; 35 from 5001 to 10 000; 8 of 10 001 to 20 000; 6 of 20 001 to 50 000; 5 of 50 001 to 100 000 and 4 municipalities with more than 100 000 inhabitants. The latter are: Valladolid (306 830 hab.), Burgos (177 776 hab.), Salamanca (148 042 hab.) And León (129 551 hab.) Among the least populated are, between others: Jaramillo Quemado (Burgos), with 4 inhabitants, Estepa de San Juan (Soria), with 7, Quiñonería (Soria), with 8 and Villanueva de Gormaz (Soria), with 9.

Below is a table showing the 20 municipalities with the largest population according to the municipal census of the INE of 2015:

Religion

Catholicism is the predominant religion in the community. According to the barometer of the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS) conducted in October 2019, 76.8% of Castilian-Leonese are considered Catholics (43.2 Non-Practising and 33.6% Practising), non-believers 20.3%

However, church attendance it's very different. According to the same study, Catholics or another religion-believers who say they rarely if ever attend mass or other religious services make up 50% of the religious respondents. 17.4% say they go several times a year, while 20.6% say they attend religious services very Sunday and public holidays, 7.4% do so two or three a month, and 2.7% say they go several times a week.[21]

Foreign population

| Nationality | Population |

|---|---|

| 23,674 | |

| 20,281 | |

| 19,816 | |

| 7,962 | |

| 5,390 | |

| 3,876 | |

| 3,785 | |

| 3,553 | |

| 2,525 | |

| 2,182 | |

| Other | 30,531 |

As of 2018, the region had a foreign population of 123,575.[22] The largest groups of foreigners were those of Romanian, Bulgarian, Moroccan and Portuguese citizenship.[22]

Languages

A large part of the "Route of the Castilian language" passes through the autonomous community, which indicates the importance traditionally attributed to this land in the origin and subsequent development of that language. In the province of Burgos begins its journey, due both to being the birthplace of the language according to Ramón Menéndez Pidal, and the famous Cantar de Mio Cid. Valladolid stands out for having been the residence of the author of Don Quixote, Miguel de Cervantes, as well as authors such as José Zorrilla or Miguel Delibes and the thrust of its University. In Ávila the mystical writers St. Teresa of Ávila and St. John of the Cross stand out. Finally, Salamanca and its University have given rise to great works for the Castilian language, such as Lazarillo de Tormes or La Celestina. Professors of its University as the writer Miguel de Unamuno also give the city great importance in the evolution of the language. To conclude, Campos de Castilla, by the Andalusian writer Antonio Machado, whose theme predominates the admiration for the Castilian lands, focusing mainly on Province of Soria.

Regarding the first testimonies of the Castilian language, in the Abbey of Santo Domingo de Silos a very old beatus, the Silos Beatus is preserved. The Glosas Silenses come from that Monastery. Also in Castilian lands is the Monastery of San Pedro de Cardeña, place where the Cardeña Beatus was written. In addition, the Statute of Autonomy of the community itself mentions the Cartularies of Valpuesta and the Nodicia de kesos as the most primitive traces of Castilian (Spanish) language. The Instituto Castellano y Leonés de la Lengua is responsible for carrying out various scientific works in this regard.

In addition to the Castilian language, in Castile and León two other languages or linguistic varieties are spoken in small areas of the community: the Leonese language, that "will be subject to specific protection [...] because of its particular value within the Community's linguistic heritage" (This dialect is only spoken for less than 2000 people, what means this "will be subject to specific protection [...] because of its particular value within the Community's linguistic heritage" is not accomplished) and Galician language, which, according to the Statute of Autonomy, "will enjoy respect and protection in the places where it is usually used" (fundamentally, in the border areas with Galicia of the comarcas of El Bierzo and Sanabria). In the Salamancan comarca of El Rebollar, a modality of Extremaduran language is spoken (of the Asturian-Leonese branch)[24] known as Palra d'El Rebollal. In Merindad de Sotoscueva (province of Burgos) a Castilian is spoken with some dialectal features of the Asturian-Leonese.[25]

Administration and politics

Territorial organization

The community is formed from nine provinces: Province of Ávila, Province of Burgos, Province of León, Province of Palencia, Province of Salamanca, Province of Segovia, Province of Soria, Province of Valladolid and Province of Zamora. The provincial capitals fall in the homonymous cities to their corresponding provinces.

The concurrence of some peculiar geographic, social, historical and economic characteristics in the Leonese region of the El Bierzo is recognized, being created in 1991 the homonymous region,[26] the only Castilian-Leonese recognized by law, administered by a Comarcal Council.

| Province | Capital | Area (km2)[27] | Population (2011)[28] | Municipalities[29] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ávila | 8 050.15 | 171 647 | 248 | |

| Burgos | 14 291.81 | 372 538 | 371 | |

| León | 15 580.83 | 493 312 | 211 | |

| Palencia | 8 052.51 | 170 513 | 191 | |

| Salamanca | 12 349.95 | 350 018 | 362 | |

| Segovia | 6 922.75 | 163 171 | 209 | |

| Soria | 10 306.42 | 94 610 | 183 | |

| Valladolid | 8 110.49 | 532 765 | 225 | |

| Zamora | 10 561.26 | 191 613 | 248 |

Provision of services

.svg.png.webp)

The new territorial arrangement approved by Law 7/2013, on Planning, Services and Government of the Territory of the Community of Castile and León, establishes that the geographical spaces delimited for the provision of services are the basic unit of territorial planning and services (UBOST) -urban or rural- and functional areas -stable or strategic-.[30] Also, the new ordination determines that the mancommunities of common interest are entities for the fulfillment of their specific purposes, which may be declared when their territorial scope substantially agrees with an UBOST or several contiguous ones.[31]

This ordination is still in the implementation phase, and in September 2015 the draft map dividing the autonomous community was presented in 147 rural UBOST and 15 urban UBOST.[32]

Autonomous institutions

The Statute of Autonomy does not explicitly establish one capital. Initially the Cortes were installed provisionally in Burgos; the possibility of fixing a capital in Tordesillas was also discussed, although the final decision was to install the Cortes provisionally in the castle of Fuensaldaña.

Finally, through the autonomous laws 13/1987 and 14/1987, approved simultaneously, it was decided respectively to establish that the Junta de Castilla y León -the government of the Community-, its president, and the Cortes -the legislative body- had its headquarters in the city of Valladolid; and that the Upper Court of Justice of Castile and León had its headquarters in Burgos. The main autonomous institutions are the following:

- Junta de Castilla y León (Regional Government of Castile and León), with headquarters in Valladolid, is the regional executive, formed by the President of the Regional Government, the vice presidents and the councilors

- Cortes de Castilla y León (Parliament of Castile and León), based in Valladolid

- Tribunal Superior de Justicia de Castilla y León (Upper Court of Justice of Castile and León), based in Burgos

- Consejo Consultivo de Castilla y León (Advisory Council of Castile and León), based in Zamora

- Consejo de Cuentas de Castilla y León (Council of Accounts of Castile and León), with headquarters in Palencia

- Procurador del Común (Ombudsman), based in León

- Consejo Económico y Social de Castilla y León (Economic and Social Council of Castile and León), based in Valladolid

Cortes of Castile and León

During the first legislature, the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party was the party with the most representation in Cortes, being the first president of the community the Socialist Demetrio Madrid. Since the 1990s, regional policy has been framed by a series of absolute majorities of the People's Party, which continues to comfortably govern at present. Other national parties with presence in the community, either locally or regionally, are United Left (previously as Communist Party of Spain) and Union, Progress and Democracy, with a significant presence in the provinces of Ávila and Burgos. Previously Democratic and Social Centre of Adolfo Suárez also managed to be in the regional political life occupying the reformist center of the political spectrum.

The Leonesism through the Leonese People's Union, the Castilianism through Party of Castile and León, previously Commoners' Land or localistas parties like Independent Solution, Group of Zamoran Independent Electoral Members or Initiative for the Development of Soria have also had their presence, although at a lower level.

The community is governed by Alfonso Fernández Mañueco, of the People's Party. This party obtained 29 procurators in the 2019 Castilian-Leonese regional election. Mañueco's investiture was supported by the party Citizens, with 12 representatives. The party that obtained the most seats at the election, the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party is in opposition, with 35 representatives. The leader of the opposition is Luis Tudanca. In addition, four more formations obtained parliamentary representation in the region: Podemos (2 seats), Vox (1), XÁvila (1) and Leonese People's Union (1).

Economy

The Gross domestic product (GDP) of the autonomous community was 57.9 billion euros in 2018, accounting for 4.8% of Spanish economic output. GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power was 25,800 euros or 85% of the EU27 average in the same year. The GDP per employee was 97% of the EU average.[33]

Unemployment rate

In July 2009, in full Great Recession, unemployment reached 14.14% of the population,[34] when in 2007 it was half, 6,99 %.[35] According to the survey of the employment of the fourth quarter of 2014, the employment rate is 54.91% and the unemployment rate is 20.28%, while the national figure is 59,77 % of employment and 23.70% of unemployed. Below the regional average of unemployment are Segovia (14.33%), Valladolid (16.65%), Soria (16.96%) and Burgos (18.76%), while above Salamanca (21,25%), León (22.65%), Palencia (23.22%), Ávila (25.33%) and Zamora (26.62%).[36]

The unemployment rate stood at 14.1% in 2017 and was slightly lower than the national average.[37]

| Year | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unemployment rate (in %) |

8.1% | 7.1% | 9.6% | 14.0% | 15.8% | 16.9% | 19.8% | 21.7% | 20.8% | 18.3% | 15.8% | 14.1% |

Primary sector

- Field

The fields of Castile and Leon are arid and dry although very fertile, predominating in them the dryland farming. Despite this, irrigation has been gaining importance in the areas of the valleys of Douro, Esla, Órbigo, Pisuerga and Tormes. The scarce orography and the improvement of communications has favored the entry of technical innovations throughout the process of agricultural production, especially in areas such as the province of Valladolid or the province of Burgos where the production per hectare is one of the highest in Spain. The most fertile Castilian-Leonese area coincides with the Esla valley, in León, in the fields of Valladolid and Tierra de Campos, a district that extends between province of Zamora, province of Valladolid, province of Palencia and province of León.

- Use of arable land

Castile and León has an agricultural area close to 5,783,831 hectares, which is more than half of the total area of its total territory. Most of the farmland is dryland, due to the climate and the low rainfall. Only 10% of the area is irrigated, with plots of intensive production, much more profitable than dryland crops.

Despite the decline of the population in rural areas, the Castilian-Leonese agricultural production still represents 15% of the Spanish primary sector and its average occupation is lower than that of other autonomous communities.

- Types of crop

Castile and León constitutes one of the main Spanish cereal areas. As the popular saying says: "Castile, granary of Spain". Although the most traditional crop was wheat, the production of barley has gained ground since the 1960s. These two cereals are followed, in number of hectares cultivated and volume of production, rye and oats. In addition to legumes, such as carob and chickpeas, sunflower cultivation has spread in the southern countryside.

The vineyard (56,337 ha) saw the number of hectares cultivated during the last three decades of the 20th century decrease considerably; However, the application of the most modern aging techniques has notably improved the Castilian-Leonese wines, which compete in quality with those of La Rioja and begin to be known outside the Spanish borders. The main viticultural areas of the region are Ribera del Duero (DO), Rueda (DO), Toro (DO), Bierzo (DO), Arribes (DO) and Tierra de León (DO). Irrigated land is planted with sugar beet, a product that has been subsidized by the regional authorities, potatoes, alfalfa and vegetables. In the province of León, corn, hops and legumes are also sown.

- Agrarian actives

Castile and León has some 92,600 agricultural actives (around 10% of the active population), of which 88,000 are employed and 5% of the total is unemployed, according to 2001 data.

By provinces, the occupied agricultural population in Ávila is 9,400 people, in Burgos and Palencia it is 8,100, in León 18,300 people work in the sector, in Salamanca about 9,200, in Segovia some 6,400, in Soria 5,600, in Valladolid 8,300 and in Zamora about 14,600 people. The agricultural and livestock sector of the region represents 7.6% of the total in Spain.

- Livestock

Livestock represents an important part of the final agricultural production. Next to the small livestock units, which proliferate in the regions of pre-eminent agricultural dedication or in the mountain areas, now appears a modern livestock activity, with cattle, pig and sheep farms, of development. These farms are oriented both to the production of meat and to the supply of milk to the cooperatives that channel their subsequent commercialization, since the dairy production of Castile and León -more than one and a half million liters per year- is the second largest in Spain, only surpassed by Galicia.

Thus, small livestock farms tend to disappear, largely due to the effect of rural depopulation and the consequent loss of labor. Transhumant grazing is conserved in some areas; large herds, mainly sheep, travel every year hundreds of kilometers from the flat lands to the land with mountain pastures as in the El Bierzo, the Cantabrian valleys of province of León, the sierra de Gredos or Picos de Urbión. It is hard work that every time has less labor, having previously constituted a testimony of first importance on the history and cultural roots of the Castilian and Leonese people.

The sheep herd is the most numerous, with 5,425,000 heads, followed by domestic pig (2,800,000) and cattle (1,200,000). A long way away is the goats (166,200 heads) and horses (71,700 horses, mules and donkeys). The highest production of meat corresponds to that of pigs (241,700 t), followed by bovine (89,400 t) and poultry (66,000 t); in wool production Castile and León leads the national balance with 7,500 t. Within the section of Protected Geographical indication (I.G.P), highlights Lechazo de Castilla y León, based in Aranda de Duero.

- Forest exploitation

In Castile and León there are about 1,900,000 hectares of non-arboreal, representing 40% of the total forest area. This deforestation is mainly due to the hand of the man who, over the centuries, has made forests disappear, giving way to areas of non-arboreal vegetation. Little by little, with the abandonment of rural areas and the reforestation policy of the Castilian and Leonese governments, this situation has been reversed.

Secondary sector

- Industry

_Visita_a_Aciturri_y_Montefibre_(Miranda_de_Ebro)_02.jpg.webp)

During 2000, the Castile and León industry occupied 18% of the active population and contributed 25% of GDP. The most developed industrial axis is that of Valladolid-Palencia-Burgos-Miranda de Ebro-Aranda de Duero, where there is an important car industry, paper industry, aeronautics and chemistry, and is where most of the industrial activity of the Castilian-Leonese territory is concentrated. The food industry derived from the farm and livestock, with flour, sunflower oil and wines, among others is also important, especially in the Ribera del Duero comarca, especially in Aranda de Duero.

The main industrial poles of the community are: Valladolid (21,054 workers dedicated to the sector), Burgos (20,217), Aranda de Duero (4,872), León (4,521), Ponferrada (4,270) and Ólvega (4,075).[38]

Other industries are textiles in Béjar, roof tiles and bricks in Palencia, sugar in León, Valladolid, Toro, Miranda de Ebro and Benavente, the pharmaceutical company in León, Valladolid and mainly in Aranda de Duero with a factory of the GlaxoSmithKline group, the metallurgical and steel company in Ponferrada and the chemistry in Miranda de Ebro and Valladolid, the aeronautics in Miranda de Ebro and Valladolid. In the remaining capitals there is a food industry derived from the agricultural and livestock exploitation, with flour, sunflower oil and wines, among others. This regional agro-food industry is flagged by Calidad Pascual based in Aranda de Duero. In the agricultural industry, within the production of fertilizers, the Mirat, founded on 1812 in Salamanca, stands out.[39]

In Soria the logging industry and furniture manufacturing is also relevant to the regional economy.

The president of the Castilian-Leonese employers' association is currently Ginés Clemente, owner of the Aciturri Aeronáutica, based in Miranda de Ebro. It is a leading international aeronautical group, with contracts with groups such as Boeing and Airbus, which makes Castile and León a benchmark in the sector.

- Construction

The 16,34 % of the companies in Castile and León belong to the auxiliary sector of construction. Among the largest companies in the sector, the following stand out: Grupo Pantersa, Begar, Grupo MRS, Isolux Corsán, Llorente Corporation, Volconsa and of auxiliary construction sector, Artepref of Gerardo de la Calle Group.[40]

- Mining

In Castile and León, the mining activity acquired great importance in the Roman times, when a road was drawn, the Vía de la Plata, to transfer the gold extracted in the deposits of Las Médulas, in the Leonese comarca of El Bierzo, the route started from Asturica Augusta (Astorga) to Emerita Augusta (Mérida) and Hispalis (Seville).

Centuries later, after the Spanish Civil War, mining was one of the factors that contributed to the economic development of the region. However, the production of iron, tin and tungsten decreased notably from the 1970s, while bituminous coal and anthracite mines were maintained thanks to the domestic demand for coal for thermal power plants. The economic reconversion that affected the Leonese mining basin and Palencian mining basin during the 1980s and 1990s resulted in the closure of numerous mines, social impoverishment, with a sharp increase of unemployment and the beginning of a new migratory movement towards other Spanish regions. Despite the investments of the Mining Action Plan of the Junta de Castilla y León, traditional coal mining operations have entered into a severe crisis.

- Energy sources

In addition to the northern basin, in those of the Douro and Ebro rivers there are numerous hydroelectric plants that allow Castile and León to be one of the first autonomous communities producing electricity. Among others are those of Burguillo, Rioscuro, Las Ondinas, Cornatel, Bárcena, Aldeadávila I and II, Saucelle I and II, Castro I and II, Villalcampo I and II, Valparaíso and Ricobayo I and II.

The total installed hydraulic power amounts to 3,979 MW[41][42] and annual production in 2010 was 5,739 GWH.[42] Only in the system Saltos del Duero there are more than 3000 MW installed. In this way, Castile and León is the first Spanish autonomous community in installed capacity and the second in production.[42]

The nuclear power is 466 MW, having produced 3,579.85 GWh in 2009. The only nuclear plant in Castile and León on August 1, 2017 was definitively and irrevocably closed.

The coal thermal produces around 16,956 GWh per year at the following plants:

- Thermal power stations in Castile and León

| Name | Location | Province | Owner |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal power station of Anllares | Páramo del Sil | Province of León | Gas Natural Fenosa and Endesa |

| Thermal power station of Compostilla II | Cubillos del Sil | Province of León | Endesa |

| Thermal power station of La Robla | La Robla | Province of León | Unión Fenosa |

| Velilla Power Plant | Velilla del Río Carrión | Province of Palencia | Iberdrola[43] |

This community stands out for the importance of the production of renewable energy. Castile and León is the community that covers the largest proportion of its electricity demand through renewable energies: 82,9 % in 2009.[44] Traditional hydroelectric power It has been added with force since the late 1990s and 2000 wind power, with more than 100 parks in operation and a production of 5,449 GWh in that same year. By provinces, it is at the top Burgos with 46, and a total of 3,128 MW of installed power.

Among the non-renewable energies is also the natural gas (194 MW of installed power) and fuel-diesel fuel (69 MW).

The provinces of Valladolid and Burgos are the most economically advanced regions, with a GDP per capita higher than the national average. Even so, the average GDP per capita of the community of Castile and León is slightly below than average, at 21,244 euros per inhabitant.

Tourism

Throughout the 1990s, the tourist influx to Castile and León grew, favored above all by the historical and cultural value of its cities and also by the natural and scenic attractiveness of its different comarcas. In 2001, Castile and León received some 315,000,000 visitors, 42,000,000 of whom were foreigners. The World Heritage cities: Ávila, Salamanca and Segovia; the Way of St. James that passes through the provinces of Burgos, Palencia and León, and the ducal town of Lerma, are the mainstays of cultural tourism in Castile and León.

As for related tourism the practice of winter sports include several ski resorts, such as La Covatilla in the Sierra de Béjar, San Isidro and Leitariegos in province of León or La Pinilla in province of Segovia.

Another attractive increasingly booming is rural tourism. In a large number of towns in the community rural houses are being valued accommodating them for a type of tourism alternative to "sun and beach". They are usually close to natural areas or areas of high heritage or ecological value.

Castile and León has several cities whose Holy Week is considered to be of International Tourist Interest. Examples are Holy Week in León, Holy Week in Salamanca, Holy Week in Valladolid or Holy Week in Zamora.[45]

The region also has a wide network of Paradores, hotels of great quality that usually accommodate buildings of great historical value in privileged places to stimulate tourism in the area.

Since 1988, the foundation Las Edades del Hombre has been organizing various exhibitions of religious art in various parts of the national and international geography, highlighting for its interest the exhibitions held in Castile and León. The idea of carrying out these exhibitions was conceived in a chimney of Alcazarén with the writer José Jiménez Lozano and the priest of Valladolid José Velicia. The first "Las Edades del Hombre" were held in the Church of Santiago Apóstol of Alcazarén, with a small exhibition of sacred paintings. Later, and with the support of important personalities, the first known exhibition was held among the public, which was that of Valladolid. In 2012 the initiative was developed under the name of Monacatus in the town of Oña, being one of the most multitudinous editions with about 200 000 visitors.[46] The last sample so far has taken place in the municipality of Arévalo, in 2013. With the title of Credo, the exhibition has revolved around the faith and has received more than 226 000 visitors.[47]

Domestic trade and exports abroad

The internal trade of Castile and León is concentrated in the sector of food, automotive, fabric and footwear. For foreign trade, according to the region, vehicles and car chassis are mainly exported in Province of Ávila, Province of Palencia and Province of Valladolid, tires in Province of Burgos and Province of Valladolid, steel bars and slate manufactures in León, beef in Province of Salamanca, pigs in Province of Segovia, rubber manufactures in Province of Soria and goat and sheep meat, together with wine, in Province of Zamora.

Castile and León also exports a lot of wine, being Province of Valladolid the one that more bottles sells abroad. As regards imports, vehicles and their accessories, such as engines or tires, are in the lead. The Region also imports mainly products from France, Italy, United Kingdom, [Germany, [Portugal and the United States and exports mostly to the countries of the European Union and to Turkey, Israel and United States.

There is a firm commitment to the manufacture in Castile and León of electric cars, as a bet to give continuity in the future to the automotive industry of the community.

Culture

Education

- Universities

- Public

- Private

- Catholic University of Ávila (Universidad Católica Santa Teresa de Jesús de Ávila)

- Miguel de Cervantes European University (Valladolid)

- IE University (Instituto de Empresa Universidad, Segovia)

- Pontifical University of Salamanca

Literature

Juan del Encina is widely considered the most important renacentist writer.

Classic baroque El Lazarillo de Tormes of the Golden Age as well as mystic San Juan de la Cruz and Santa Teresa de Jesús.

José Zorrilla wrote Don Juan Tenorio in the SXIX century.

During the XX century, Miguel Delibes wrote about the rural flight of the 1950s, in books as El Hereje, Los santos inocentes or Cinco horas con Mario.

Transportation

Rail

Castilla y León has an extensive rail network, including the principal lines from Madrid to Cantabria and Galicia. The line from Paris to Lisbon crosses the region, reaching the Portuguese frontier at Fuentes de Oñoro in Salamanca. Astorga, Burgos, León, Miranda de Ebro, Palencia, Ponferrada, Medina del Campo and Valladolid are all important railway junctions.

Railways operate in several different gauges: Iberian gauge (1,668 mm (5 ft 5 21⁄32 in)), UIC gauge (1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in)) and Narrow gauge (1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in)). Except for some narrow-gauge lines, trains are operated by RENFE on lines maintained by the Administrador de Infraestructuras Ferroviarias (ADIF); both of these are national, state-owned companies.

Iberian gauge lines (ADIF/RENFE)

- Madrid - Irun

- Madrid - Burgos

- Castejón de Ebro - Bilbao

- Venta de Baños - A Coruña

- Palencia - Santander

- León - Gijón

- Medina del Campo - Santiago de Compostela

- Medina del Campo - Fuentes de Oñoro

- Torralba - Soria

- Villalba - Segovia

Narrow gauge

- León - Bilbao: Ferrocarril de La Robla, Europe's longest narrow-gauge line, operated by FEVE

- Cercedilla - Cotos: operated by RENFE

- Ponferrada - Villablino: operated by the Ferrocarril MSP under the Junta of Castile and León

Roads

The region is also crossed by two major ancient routes:

- The Way of St. James, mentioned above as a World Heritage Site, now a hiking trail and a motorway, from east to west.

- The Roman Via de la Plata ("Silver Way"), mentioned above in the context of mining, now a main road through the west of the region.

The road network is regulated by the Ley de carreteras 10/2008 de Castilla y León (Highway Law 10/2008 of Castile and León).[48] This law allows for the possibility of roads financed by the private sector through concessions, as well as the public construction of roads that has long prevailed.

References

- Informational notes

- Also; Asturian: Castiella y Llión (Leonese dialect) ([kasˈtjeʎa i ʎiˈoŋ]) and Galician: Castela e León Galician pronunciation: [kasˈtɛlɐ ɪ leˈoŋ]).

- Citations

- "Contabilidad Regional de España. Base 2010. Producto Interior Bruto regional. Serie 2010-2018" (PDF). Instituto Nacional de Estadística. April 29, 2019.

- "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- María R. Mayor (June 19, 2013), "Unesco recognizes León as the worldwide cradle of parliamentarism", El Mundo (newspaper)

- Cortes Generales (1995), "Organic Law 10/1995, of November 23 , of the Penal Code" (PDF), Boletín Oficial del Estado no. 281, of November 24, 1995, Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado

- "The Decreta of León of 1188 - The oldest documentary manifestation of the European parliamentary system - United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.UNESCO.org. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- "El Santo Grial eleva un 30% las visitas a San Isidoro y genera nuevo empleo". ElNorteDeCastilla.es. August 13, 2014. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- "¿Está el Santo Grial en León?". ABC.es. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- Juan-Miguel Álvarez Domínguez.The Regionalist Catechism of Don Eugenio, an example of Castilian-Leonese regionalism sponsored by León. 1931, Argutorio, No. 19 (2nd semester 2007), pp. 32-36.

- Alejandro De Haro Honrubia. "La propuesta autonomista de Ortega y Gasset: un claro antecedente de la configuración autonómica del Estado español de 1978" (PDF). University of Castilla-La Mancha.

- El País (newspaper). "Seis grupos políticos se fusionan en un partido regionalista en Castilla y León".

- Diario de León (newspaper), May 5, 1984.

- Diario de León, March 13, 2004.

- "Fundación Villalar Castilla y León". Archived from the original on March 31, 2016. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- Castile and León Regional Government. "Premios Castilla y León" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on December 25, 2013.

- "Grupo Espeleologico Edelweiss 2010". GrupoEdelweiss.com. Archived from the original on December 26, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- Bulletin of the AGE. "Riesgos climáticos en Castilla y León. Análisis de su peligrosidad" (PDF).

- http://www.divulgameteo.es/fotos/meteoroteca/Monta%C3%B1as-clima-LGP.pdf

- AEMET. "Atlas climático ibérico" (PDF).

- Internet, Unidad Editorial. "Los bisontes regresan a la península mil años después de su desaparición - Castilla y León - elmundo.es". www.ElMundo.es. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- Ribeiro, Ana Isabel; Krainski, Elias Teixeira; Carvalho, Marilia Sá; Pina, Maria de Fátima de (February 15, 2016). "Where do people live longer and shorter lives? An ecological study of old-age survival across 4404 small areas from 18 European countries". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 70 (6): jech–2015–206827. doi:10.1136/jech-2015-206827. ISSN 1470-2738. PMID 26880296. S2CID 6304476.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos - Document 'Población con derecho a voto en elecciones generales y residente en España, Castilla y León (aut.)" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 24. Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- "Población extranjera por Nacionalidad, comunidades, Sexo y Año". Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Archived from the original on April 26, 2019. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- www.alfaprocesos.com, www.serviciosintegralesweb.com División de. "NOTICIA". www.FundacionCantera.org. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- Hablas de Extremadura: Frontera Leonesa Archived April 30, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- Silvia González Goñi. "Apuntes sobre el habla de la Merindad de Sotoscueva (Burgos): léxico" (PDF). Alcuentros. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- LAW 1/1991 of March 14, by which is created and regulates the region of El Bierzo. Date of the B.O.C.Y.L .: March 20, 1991 No. Bulletin: 55/1991

- "Población superficie y densidad por CCAA y provincias". Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- "Censos de Población y Viviendas 2011. Resultados nacionales por Comunidades autónomas y provincias". Instituto Nacional de Estadística.

- "Cifras oficiales de población resultantes de la revisión del Padrón municipal a 1 de enero de 2011". Instituto Nacional de Estadística.

- "Ley 7/2013, de 27 de septiembre, de Ordenación, Servicios y Gobierno del Territorio de la Comunidad de Castilla y León" (PDF), Boletín Oficial de Castilla y León num. 189, of October 1, 2013, Junta de Castilla y León, pp. 65222–65273, ISSN 1989-8959

- Boletín Oficial de Castilla y León: DECREE 30/2015, of April 30, which approves the Regulation of Organization and Operation of the Mancommunities of General Interest.

- León, Junta de Castilla y. "La Junta presenta el primer borrador de unidades básicas de ordenación del territorio, abierto a aportaciones previas a la propuesta inicial para su tramitación". www.comunicacion.jcyl.es. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- "Regional GDP per capita ranged from 30% to 263% of the EU average in 2018". Eurostat.

- www.rtvcyl.es (January 21, 2018). "Radio Televisión de Castilla y León". rtvcyl.es. Archived from the original on January 21, 2018. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- Mundinteractivos. "El paro bajó en Castilla y León un 5% frente a un incremento nacional del 6,5 - elmundo.es". www.ElMundo.es. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- "Encuesta de población activa del cuarto trimestre 2014" (PDF). Instituto Nacional de Estadística.

- "Regional Unemployment by NUTS2 Region". Eurostat.

- "Fichas Municipales - 2008 DATOS ECONÓMICOS Y SOCIALES". 2009. Archived from the original on December 22, 2009.

- "Las 5000 mayores empresas", Castilla y León Económica (153), 2009

- "Ranking 2009 de las 5.000 mayores empresas de Castilla y León - year = 2010". 2010. Archived from the original on August 31, 2010.

- "La potencia instalada en energías renovables se multiplica por diez en los últimos ocho años". Archived from the original on December 22, 2009.

The installed power in 2006 is distributed as follows: 3,979 megawatts in hydraulic, 2,707 in coal and 466 in nuclear

- "Lluvia de megavatios", El Norte de Castilla (newspaper), 2011,

Hydraulic production exceeded 5,739 Gwh in the region. By installed power, Castile and León is the leading Spanish region, with a total of 3,979 megawatts (MW) of power, ahead of Galicia

- Terra: Iberdrola contrata con Izar mantenimiento central térmica Velilla.

- Annual Report of Red Eléctrica de España 2008

- BOE. "Publication in the BOE of the RESOLUTION of March 14, 2003, of the General Secretariat of Tourism, by which the title of "Festival of International Tourist Interest" is granted to Holy Week in Salamanca".

- http://www.elmundo.es/elmundo/2012/11/03/castillayleon/1351963961.html

- El Confidencial. "El presidente de la Fundación destaca interés de "Las Edades" durante 25 años".

- Ha entrado en vigor la nueva Ley de carreteras de Castilla y León que regula la planificación, proyección, construcción, conservación, financiación, uso y explotación de las carreteras con itinerario comprendido íntegramente en el territorio de la Comunidad Autónoma de Castilla y León y que no sean de titularidad del Estado. Archived April 29, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Castile and León. |

- Cortes de Castilla y León (Regional Parliament) (in Spanish)

- Junta de Castilla y León (Regional Government) (Mostly in Spanish)

- The Cortes of Castile-León, Joseph F. O'Callaghan (historical)

- Tourist Information

.jpg.webp)