Carotid artery dissection

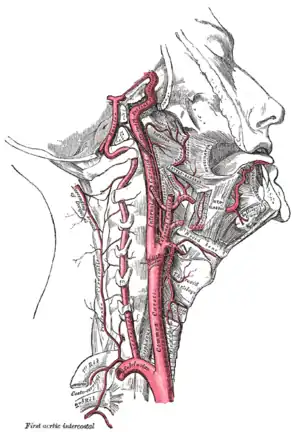

Carotid artery dissection is a separation of the layers of the artery wall supplying oxygen-bearing blood to the head and brain and is the most common cause of stroke in young adults.[1] (In vascular medicine, dissection is a blister-like de-lamination between the outer and inner walls of a blood vessel, generally originating with a partial leak in the inner lining.)[2]

| Carotid artery dissection | |

|---|---|

| |

| Specialty | Vascular surgery |

Dissection may occur after physical trauma to the neck, such as a blunt injury (e.g. traffic collision), strangulation, but may also happen spontaneously.[3]

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of carotid artery dissection may be divided into ischemic and non-ischemic categories:[4]

Non-ischemic signs and symptoms

- Localised headache, particularly around one of the eyes.

- Neck pain

- Decreased pupil size with drooping of the upper eyelid (Horner syndrome)

- Pulsatile tinnitus

Ischemic signs and symptoms

- Temporary vision loss

- Ischemic stroke

Causes

The causes of internal carotid artery dissection can be broadly categorised into two classes: spontaneous or traumatic.

Spontaneous

Once considered uncommon, spontaneous carotid artery dissection is an increasingly recognised cause of stroke that preferentially affects the middle-aged.[5]

The incidence of spontaneous carotid artery dissection is low, and incidence rates for internal carotid artery dissection have been reported to be 2.6 to 2.9 per 100,000.[6]

Observational studies and case reports published since the early 1980s show that patients with spontaneous internal carotid artery dissection may also have a history of stroke in their family and/or hereditary connective tissue disorders, such as Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, fibromuscular dysplasia, and osteogenesis imperfecta type I.[7] IgG4-related disease involving the carotid artery has also been observed as a cause.[8]

However, although an association with connective tissue disorders does exist, most people with spontaneous arterial dissections do not have associated connective tissue disorders. Also, the reports on the prevalence of hereditary connective tissue diseases in people with spontaneous dissections are highly variable, ranging from 0% to 0.6% in one study to 5% to 18% in another study.[7]

Internal carotid artery dissection can also be associated with an elongated styloid process (known as Eagle syndrome when the elongated styloid process causes symptoms).[9][10]

Traumatic

Carotid artery dissection is thought to be more commonly caused by severe violent trauma to the head and/or neck. An estimated 0.67% of patients admitted to the hospital after major motor vehicle accidents were found to have blunt carotid injury, including intimal dissections, pseudoaneurysms, thromboses, or fistulas.[11] Of these, 76% had intimal dissections, pseudoaneurysms, or a combination of the two. Sports-related activities such as surfing[12] and Jiu-Jitsu[13] have been reported as causes of catorid artery dissection.

The probable mechanism of injury for most internal carotid injuries is rapid deceleration, with resultant hyperextension and rotation of the neck, which stretches the internal carotid artery over the upper cervical vertebrae, producing an intimal tear.[11] After such an injury, the patient may remain asymptomatic, have a hemispheric transient ischemic event, or suffer a stroke.[14]

Artery dissection has also been reported in association with some forms of neck manipulation.[3] There is significant controversy about the level of risk of stroke from neck manipulation.[3] It may be that manipulation can cause dissection,[15] or it may be that the dissection is already present in some people who seek manipulative treatment.[16][17] At this time, conclusive evidence does not exist to support either a strong association between neck manipulation and stroke, or no association.[3]

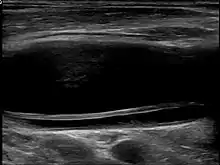

Pathophysiology

Arterial dissection of the carotid arteries occurs when a small tear forms in the innermost lining of the arterial wall (known as the tunica intima). Blood is then able to enter the space between the inner and outer layers of the vessel, causing narrowing (stenosis) or complete occlusion. The stenosis that occurs in the early stages of arterial dissection is a dynamic process and some occlusions can return to stenosis very quickly.[18] When complete occlusion occurs, it may lead to ischaemia. Often, even a complete occlusion is totally asymptomatic because bilateral circulation keeps the brain well perfused. However, when blood clots form and break off from the site of the tear, they form emboli, which can travel through the arteries to the brain and block the blood supply to the brain, resulting in an ischaemic stroke, otherwise known as a cerebral infarction. Blood clots, or emboli, originating from the dissection are thought to be the cause of infarction in the majority of cases of stroke in the presence of carotid artery dissection.[18] Cerebral infarction causes irreversible damage to the brain. In one study of patients with carotid artery dissection, 60% had infarcts documented on neuroimaging.[6]

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to prevent the development or continuation of neurologic deficits. Treatments include observation, anticoagulation, stent implantation and carotid artery ligation.

Epidemiology

70% of patients with carotid arterial dissection are between the ages of 35 and 50, with a mean age of 47 years.[1]

References

- Amal Mattu; Deepi Goyal; Barrett, Jeffrey W.; Joshua Broder; DeAngelis, Michael; Peter Deblieux; Gus M. Garmel; Richard Harrigan; David Karras; Anita L'Italien; David Manthey (2007). Emergency medicine: avoiding the pitfalls and improving the outcomes. Malden, Mass: Blackwell Pub./BMJ Books. pp. 46. ISBN 978-1-4051-4166-6.

- "Mount Sinai Hospital Patient Care Health Library"

- Haynes MJ, Vincent K, Fischhoff C, Bremner AP, Lanlo O, Hankey GJ (2012). "Assessing the risk of stroke from neck manipulation: a systematic review". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 66 (10): 940–947. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.03004.x. PMC 3506737. PMID 22994328.

- Kerry R, Taylor AJ (2006). "Cervical arterial dysfunction assessment and manual therapy". Manual Therapy. 11 (4): 243–53. doi:10.1016/j.math.2006.09.006. PMID 17074613.

- In: Neurology 2006;67:1809-1812. Mokri B (1997). "Spontaneous dissections of internal carotid arteries". Neurologist. 3 (2): 104–119. doi:10.1097/00127893-199703000-00005.

- Lee VH, Brown Jr RD, Mandrekar JN, Mokri B (2006). "Incidence and outcome of cervical dissection; a population-based study". Neurology. 67 (10): 1809–1812. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000244486.30455.71. PMID 17130413.

- De Bray JM, Baumgartner RW (2005). "History of spontaneous dissection of the cervical carotid artery". Arch Neurol. 62 (7): 1168–1170. doi:10.1001/archneur.62.7.1168. PMID 16009782.

- Andrea Barp; Marny Fedrigo; Filippo Maria Farina; Sandro Lepidi; Francesco Causin; Chiara Castellani; Giacomo Cester; Thiene; Marialuisa Valente; Claudio Baracchini; Annalisa Angelini (January–February 2016). "Carotid aneurism with acute dissection: an unusual case of IgG4-related diseases". Cardiovascular Pathology. 25 (1): 59–62. doi:10.1016/j.carpath.2015.08.006. PMID 26453089.

- Olafur Sveinsson; Nikolaos Kostulas; Lars Herrman (11 June 2013). "Internal carotid dissection caused by an elongated styloid process (Eagle syndrome)". BMJ Case Reports. 2013: bcr2013009878. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-009878. PMC 3702984. PMID 23761567.

- Takenori Ogura; Yohei Mineharu; Kenichi Todo; Nobuo Kohara; Nobuyuki Sakai (2015). "Carotid Artery Dissection Caused by an Elongated Styloid Process: Three Case Reports and Review of the Literature". NMC Case Report Journal. 2 (1): 21–25. doi:10.2176/nmccrj.2014-0179. PMC 5364929. PMID 28663957.

- Fabian TC, Patton J, Croce M, Minard G, Kudsk K, Pritchard F (1996). "Blunt Carotid Injury". Annals of Surgery. 223 (5): 513–52. doi:10.1097/00000658-199605000-00007. PMC 1235173. PMID 8651742.

- Pego-Reigosa, R.; López-López, S.; Vázquez-López, M. E.; Armesto-Pérez, V.; Brañas-Fernández, F.; Martínez-Vázquez, F.; Piñeiro-Bolaño, R.; Cortés-Laiño, J. A. (2005-06-14). "Sea wave–induced internal carotid artery dissection". Neurology. 64 (11): 1980. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000163855.78628.42. ISSN 0028-3878. PMID 15955962.

- Demartini, Zeferino; Rodrigues Freire, Maxweyd; Lages, Roberto Oliver; Francisco, Alexandre Novicki; Nanni, Felipe; Maranha Gatto, Luana A.; Koppe, Gelson Luis (June 2017). "Internal Carotid Artery Dissection in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu". Journal of Cerebrovascular and Endovascular Neurosurgery. 19 (2): 111–116. doi:10.7461/jcen.2017.19.2.111. ISSN 2234-8565. PMC 5678212. PMID 29152471.

- Matsuura JH, Rosenthal D, Jerius H, Clark MD, Owens DS (1997). "Traumatic Carotid Artery Dissection and Pseudoaneurysm Treated With Endovascular Coils and Stent". Journal of Endovascular Surgery. 4 (4): 339–343. doi:10.1583/1074-6218(1997)004<0339:TCADAP>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1074-6218. PMID 9418195.

- Ernst E (2010). "Vascular accidents after neck manipulation: cause or coincidence?". Int J Clin Pract. 64 (6): 673–7. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02237.x. PMID 20518945.

- Haas M, Brønfort G, Evans RL, Leininger B, Schmitt J, Levin M, Westrom K, Goldsmith CH (2016). "Spinal rehabilitative exercise or manual treatment for the prevention of cervicogenic headache in adults (Protocol)". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (5): CD012205. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012205. PMC 5226451. PMID 28090192.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) (Retracted, see doi:10.1002/14651858.cd012205.pub2. If this is an intentional citation to a retracted paper, please replace

{{Retracted}}with{{Retracted|intentional=yes}}.) - Guzman J, Haldeman S, Carroll LJ, et al. (February 2009). "Clinical practice implications of the bone and joint decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders: from concepts and findings to recommendations". J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 32 (2 Suppl): S227–43. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.11.023. PMID 19251069.

In persons younger than 45 years, there is an association between chiropractic care and vertebro-basilar artery (VBA) stroke; there is a similar association between family physician care and VBA stroke. This suggests that there is no increased risk of VBA stroke after chiropractic care, and that these associations are likely due to patients with headache and neck pain from vertebral artery dissection seeking care while in the prodromal stage of a VBA stroke. Unfortunately, there is no practical or proven method to screen patients with neck pain and headache for vertebral artery dissection. However, VBA strokes are extremely rare, especially in younger persons.

- Lucas C, Moulin T, Deplanque D, Tatu L, Chavot D (1998). "Stroke patterns of internal carotid artery dissection in 40 patients". Stroke. 29 (12): 2646–2648. doi:10.1161/01.STR.29.12.2646. PMID 9836779.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |