Cedar Mountain Formation

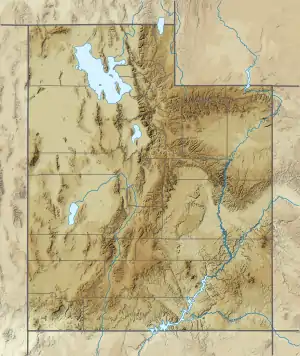

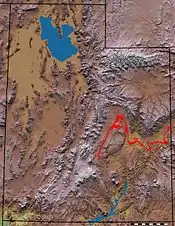

The Cedar Mountain Formation is the name given to a distinctive sedimentary geologic formation in eastern Utah. The formation was named for Cedar Mountain in northern Emery County, Utah, where William Lee Stokes first studied the exposures in 1944.[1]

| Cedar Mountain Formation Stratigraphic range: Late Berriasian-Cenomanian ~140–95 Ma | |

|---|---|

| Type | Geological formation |

| Unit of | Dakota Group |

| Sub-units | See text |

| Underlies | Naturita Formation |

| Overlies | Morrison Formation |

| Thickness | Varies, some sections over 1000 metres |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Conglomerate, sandstone, mudstone |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 40.4°N 109.3°W |

| Approximate paleocoordinates | 40.2°N 69.0°W |

| Region | |

| Country | |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Cedar Mountain |

| Named by | Stokes |

| Year defined | 1944 |

Cedar Mountain Formation (Utah) | |

Geology

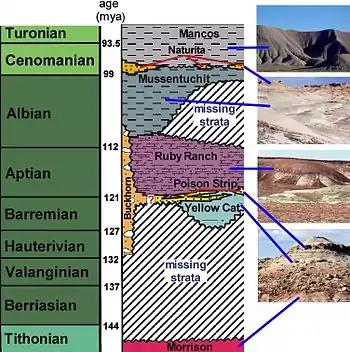

The formation occurs between the underlying Morrison Formation and overlying Naturita Formation (sometimes formerly called the Dakota Formation).

It is composed of non-marine sediments, that is, sediments deposited in rivers, lakes and on flood plains. Based on various fossils and radiometric dates, the Cedar Mountain Formation was deposited during the last half of the Early Cretaceous Epoch, about 127 - 98 million years ago (mya).

It has lithography similar to the Burro Canyon Formation in the region.

Dinosaur fossils occur throughout the formation, but their study has only occurred since the early 1990s. The dinosaurs in the lower part of the formation differ from those in the upper part. These two dinosaur assemblages, characterized by distinct dinosaurs, show the replacement of older, European-like dinosaurs with younger, Asian-like dinosaurs as the North American Continental Plate drifted westward. A middle dinosaur assemblage may be present, but the fossil record is not clear.

Stratigraphy

The Cedar Mountain Formation is sandwiched between the Morrison Formation below and the Naturita Formation and Mancos Shale above. The youngest date for Morrison just below the Cedar Mountain Formation is 148.1 ± 0.5 Ma .[2] or lower Tithonian. Typically, the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary in western North America is marked by an unconformity of variable length, and typically signifies 10-49 million years of missing geologic time.[2] This boundary between the Morrison and Cedar Mountain is commonly marked by a horizon of carbonate nodules[3][4] or by highly polished pebbles that are allegedly gastroliths.

Although not part of the Cedar Mountain Formation, the Naturita Formation immediately overlies the Cedar Mountain and marks the encroaching Western Interior Seaway. The Naturita is not uniformly distributed and was eroded away in places by the advancing Seaway so that the marine shales of the Mancos Formation lay directly on the Mussentuchit or its equivalent. The name Dakota Formation has been improperly used for these strata.

Missing strata either were not deposited or were deposited, but later eroded.

Formation members

Only recently did the 125 m (410 ft) thick formation get subdivided into smaller, distinctive beds called members. There is a debate as to whether there are five members[5] or four[6] depending whether the Buckhorn Conglomerate is considered to be at the top of the Morrison Formation or at the base of the Cedar Mountain Formation; most geologists and paleontologists consider it part of the Cedar Mountain Formation. In ascending order the remaining members are the Yellow Cat Member, Poison Strip Sandstone, Ruby Ranch Member, and the Mussentuchit Member. Each of these members are named after a geographic area where they were first studied.

- The Buckhorn Conglomerate is considered the lowermost member of the Cedar Mountain Formation in the region of the San Raphael Swell by Stokes.[3] It is named for exposures near Buckhorn Reservoir near Cedar Mountain. Its position immediately below the Ruby Ranch Member suggests that it may be equivalent to the channel sandstones in the Yellow Cat Member and the Poison Strip Sandstone farther to the east. This idea is strengthened by the similar composition of the gravels in these members, but a direct correlation has not yet been established.

- The Yellow Cat Member is named for exposures near the Yellow Cat mining area north of Arches National Park. It is limited to the eastern portions of the formation and is thickest near Arches National Monument. The member is composed of drab greyish mudstones and some lenses of sandstone. The mudstones were deposited on flood plains, and show evidence of ancient soil development called paleosols. The mudstones originated as flood deposits from river channels that are marked by the sandstone lenses. Formerly considered Barremian, the latest radiometric and paleopalinological studies conclude that the Yellow Member is older, with deposition occurring from the middle Berriasian to early Hauterivian stages.[5][7][8]

- The Poison Strip Sandstone was named for prominent, cliff-forming sandstones in the Poison Strip uranium district north of Arches National Monument. It is actually a series of sandstones that were deposited in river channels, and lesser amounts of mudstones and limestones that were deposited on the flood plain and small ponds. The Poison Strip Sandstone may represent a meandering river complex.[9] Based on the position of the Poison Strip between the Yellow Cat and Ruby Ranch members, it probably was latest Barremian to earliest Aptian. Carbonate growths appear on bones in the quarry from which Venenosaurus was extracted.[10]

- The Poison Strip Sandstone was the source of Tony's Bone Bed, a significant concentration of dinosaur bones. Before it was discovered, only possible Sauropelta remains and the isolated bones of sauropods and theropods had been recovered from the Poison Strip member.[11] Volunteers from the Denver Museum of Natural History discovered Tony's Bone Bed in 1998, 3.75m below the top of the member.[12] The quality of the preserved remains in Tony's Bone Bed are "highly variable". The condition of many of its fossils suggest the deposit accumulated gradually. Many of the bones seem to have been trampled before burial, and some of the ends of bones are missing and were likely removed by scavengers. None of the bones were preserved articulated with each other. All of this suggests a significant period of time between the deaths of the animals and their final entombment. Tony's Bonebed probably accumulated over time when the water in the river channel was low during the dry season.[13]

- The Ruby Ranch Member is the most widespread and distinctive member of the Cedar Mountain. It was named for exposures on the Ruby Ranch located southeast of Green River, Utah. The member is composed of maroon mudstones with irregular spheres of carbonate nodules. The nodules formed in ancient soils that developed in the mud deposited on the flood plain in a strongly seasonal, semiarid climate. Evaporation of groundwater during the dry season concentrated calcium carbonate and other minerals in the upper parts of the soil horizon. Radiometric dates place the upper portions of the Ruby Ranch in the late Aptian. Exhumed river channels in the Ruby Ranch indicate that stream flow during the Aptian was towards the northeast, the direction of the encrouching Western Interior Seaway.

- The Mussentuchit Member is the uppermost member of the Cedar Mountain Formation. It was named for exposures along Mussentuchit Wash southwest of the San Rafael Swell. It is predominantly composed of grey mudstones high in organic carbon from fossil plant material, as well as volcanic ash. The mudstones were originally deposited on a broad coastal plain with a high water table or with abundant rainfall. Thus, carbonate nodules are rare. A radiometric date of 98.37 ± 0.07 Ma places the upper part of the member in the Lower Cenomanian, while lower portions of the member have been dated to 104.46 ± 0.95 Ma, in the Albian stage.[14]

Fossil content

The Cedar Mountain Formation is proving to contain one of the richest and most diverse Early Cretaceous dinosaur faunas in the world. The discoveries to date have revealed that the origin of some of the later Cretaceous dinosaurs may lie in the Cedar Mountain, but further work is needed to understand the timing and effects the changing position of the North American Plate had on dinosaurian evolution. Also needed is a better understanding of the effects that the changing North American Plate had on the non-dinosaur vertebrates.

Dinosaurs

The Cedar Mountain Formation is one of the last major dinosaur-bearing formations to be studied in the United States. Although sporadic bone fragments were known prior to 1990, serious research did not begin until that year. Since then, several organizations have conducted field work collecting dinosaurs, chiefly the Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, the College of Eastern Utah, the Utah Geological Survey, Brigham Young University, and Dinosaur National Monument staff. This research indicates that at least two, possibly three dinosaur assemblages are contained within the formation.

The oldest of these assemblages is from the Yellow Cat, Poison Strip and basal Ruby Ranch members. The small, Ornitholestes-like theropod Nedcolbertia and the brachiosaurid sauropod Cedarosaurus may be considered as relics, with their closest relatives in the Morrison Formation. In contrast, the polacanthid ankylosaur Gastonia and a yet unnamed iguanodontid are similar to related forms from the Lower Cretaceous of southern England. These dinosaurs show that the connection between North America and Europe still existed during the Barremian. All of this changes, however, with the upper dinosaur assemblage from the top of the Ruby Ranch and Mussentuchit members. This upper assemblage shows greater similarities with Asian dinosaur assemblages from the same time. For example, the primitive ankylosaurid Cedarpelta is related to Gobisaurus and Shamosaurus from Mongolia, but is more primitive than either because it has teeth in the premaxilla. The upper assemblage also has a tyrannosaurid, a ceratopsian, and a pachycephalosaur. Although not a dinosaur, the primitive mammal Gobiconodon is known from both Mongolia and the Mussentuchit Member. Evidence for a middle dinosaur assemblage between the older and younger ones is controversial because the evidence mostly depends on a single specimen of the ornithopod Tenontosaurus from high in the Ruby Ranch Member and the sauropod Astrodon from low in the Ruby Ranch. Regardless, the upper and lower dinosaur assemblages in the Cedar Mountain Formation document the separation of North America and Europe, the westward drift of North America, and its connection with Asia 10 to 15 million years later.[15]

Data from Carpenter (2006),[15] Cifelli et al. (1999),[16] Kirkland and Madsen (2007), and The Paleobiology Database.

Ankylosaurs

| Ankylosaurs reported from the Cedar Mountain Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Member | Material | Notes | Images |

| Animantarx | Animantarx ramaljonesi |

|

"Partial skull [and] skeleton."[17] |

| ||

| Cedarpelta[18] | Cedarpelta bilbeyhallorum[18] |

|

"Skull [and] postcranium."[19] | Cedarpelta bilbeyhallorum was not from the Ruby Ranch Member as initially described.[18] | ||

| Gastonia | Gastonia burgei |

|

"[Two] skulls, [two] partial skulls, [and four] or [five] partial skeletons."[20] | |||

| G. lorriemcwhinneyae[21] |

|

|||||

| Peloroplites | Peloroplites cedrimontanus |

|

||||

| Sauropelta | Indeterminate |

|

||||

Neornithischians

A large sail-backed iguanodont represented by large vertebrae and fragmentary remains from the Upper Yellow Cat Member.[22]

| Neornithischians reported from the Cedar Mountain Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Member | Material | Notes | Images |

|

Cedrorestes crichtoni |

|

.jpg.webp) Zephyrosaurus being attacked by a Deinonychus | ||||

|

Eolambia caroljonesa |

|

|||||

|

Hippodraco scutodens |

|

|||||

|

Iguanacolossus fortis |

|

|||||

|

Iguanodon ottingeri |

"Teeth."[23] |

Dubious. | ||||

|

Planicoxa venenica |

|

"Associated postcranium." [24] |

||||

|

Tenontosaurus tiletti |

|

|||||

| Indeterminate |

|

|||||

|

Zephyrosaurus schaffi |

|

|||||

Marginocephalians

Unknown neoceratopsian present in the Mussentuchit Member. Unnamed pachycephalosaurid present in the Mussentuchit Member.

Sauropods

| Sauropods reported from the Cedar Mountain Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Member | Material | Notes | Images |

|

Abydosaurus mcintoshi |

|

| ||||

|

cf. Astrodon |

Indeterminate |

|

||||

|

Brontomerus mcintoshi |

|

|||||

|

Cedarosaurus weiskopfae |

|

"Postcranial skeleton."[25] |

||||

|

Mierasaurus bobyoungi |

|

|||||

|

Moabosaurus utahensis |

|

"Remains of at least 18 fragmentary individuals."[27] |

||||

|

Venenosaurus dicrocei |

|

"Partial postcranial skeleton."[28] |

||||

Theropods

Indeterminate allosauroid material present in the Lower Yellow Cat and Ruby Ranch Members. Indeterminate dromaeosaurine present in the Mussentuchit Member. Indeterminate velociraptorine remains present in the Mussentuchit Member. Indeterminate troodontid remains present in the Mussentuchit Member. Indeterminate therizinosaurid remains present in the Mussentuchit Member. Indeterminate dromaeosaurine remains present in the Mussentuchit Member. Possible indeterminate hesperornithiformes present in the Mussentuchit Member.

| Theropods reported from the Cedar Mountain Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Member | Material | Notes | Images |

|

cf. Acrocanthosaurus |

Indeterminate |

|

| |||

|

Indeterminate |

|

|||||

|

Falcarius utahensis |

|

|||||

|

Geminiraptor suarezarum |

|

|||||

|

Martharaptor greenriverensis |

|

|||||

|

Moros intrepidus |

|

|||||

|

Nedcolbertia justinhofmanni |

|

"Partial skeletons of [three] individuals."[29] |

||||

|

cf. Richardoestesia |

Indeterminate |

|

||||

|

Siats meekerorum |

|

"Partial postcranial skeleton of immature individual." | ||||

|

Utahraptor ostrommaysi |

|

"Skull and postcranial fragments."[30] |

||||

|

Indeterminate |

|

|||||

|

Yurgovuchia doellingi |

|

|||||

Other fossils

Besides dinosaurs, the Cedar Mountain Formation has produced a wealth of small fossils (a.k.a. microfossils), mostly teeth from a variety of vertebrates. Most of these specimens have been found in the Mussentuchit Member where they are collected by washing the rock through fine window screen. The teeth and other small fossils are picked from the residue.[16]

- Fish include primitive fresh or brackish water sharks (e.g., Hybodus) and rays (c.f., Ischyrhiza), the lungfish (Ceratodus) and several bony fishes known from vertebrae. Lungfish are able to breathe air when pond water becomes poorly oxygenated, such as during the dry season.

- Amphibians include both salamanders (e.g. Albanerpeton) and frogs, but neither is common.

- Reptiles are more abundant and better studied. These include aquatic turtles (Glyptops, Naomichelys), at least one type of snake (Coniophis), and several different lizards, including teiids (Bicuspidon), possible skinks and some extinct families (e.g., Paramacellodidae). Crocodiles are also present but their remains are fragmentary. They include Bernissartia, an unnamed atoposaurid, and unnamed pholidosaurid. At least one fragment of a large pterosaur is known from the base of the Mussentuchut Member. Unfortunately, it is too incomplete to identify to family or genus.

- Bird remains are very fragmentary because of their delicate structure. At least one aquatic bird is known. Based on the diversity of birds from the Early Cretaceous of China, other birds were probably present in Utah at this time as well.

- Mammals are the most thoroughly studied thanks to the work of Jeffrey Eaton and Richard Cifelli.[16] They include triconodonts (e.g., Astroconodon), which have the molar cusps arranged in a single row; symmetrodonts (e.g., Spalacolestes; Spalacotheridium), characterized by molars having three cusps arranged in a triangle; multituberculates (e.g., Janumys; Cedaromys; Paxacimexomys), with their multiple rows of cusps on the molars; one of the earliest marsupials (Kokopellia), and several unnamed tribotheres, characterized by molars having three cusps that are typically asymmetrically arranged.

The various vertebrates are listed by member in the list below.

Non-vertebrate fossils are more widely distributed in the Cedar Mountain Formation. These include the distinctive reproductive structures of fresh water algae that are called charophytes. Charophytes are so distinctive that they are used to correlate strata of similar age, and thus were used to show that the Yellow Cat Member was time equivalent to Barremian age strata in England.[5] Ostracods, small crustaceans with clam-like shells, also occur in fresh water deposits, along with "finger-clams" or chonchostracans. Pollen have been found in the Mussentuchit Member and are important for reconstructing the environment. In a few places, large petrified logs are known, especially from the Poison Strip. These conifer logs are over a meter in diameter and indicate the presence of trees over 30 m (100 feet). The distinct wood of the tree fern Tempskya is occasional found as well.

Data from Carpenter (2006),[15] Cifelli et al. (1999),[16] KirklaPeripheralsnd and Madsen (2007), and The Paleobiology Database.

Other reptiles

Indeterminate pterosaur remains in the Mussentuchit Member.

Crurotarsans

Indeterminate crocodilian remains present in the Yellow Cat and Ruby Ranch Members. Indeterminate pholidosaurid remains present in the Mussentuchit Member. Indeterminate atoposaurid remains present in the Mussentuchit Member.

| Crurotarsans of the Cedar Mountain Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Member | Abundance | Description | Images |

|

cf. Bernissartia |

cf. Bernissartia sp. |

|

| |||

|

Dakotasuchus kingi |

|

|||||

Lepidosaurs

| Lepidosaurs of the Cedar Mountain Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Member | Abundance | Description | Images |

|

Toxolophosaurus sp. |

|

|||||

|

Harmodontosaurus |

Harmodontosaurus emeryensis |

|

||||

|

Dimekodontosaurus |

Dimekodontosaurus madseni |

|

||||

|

Dicothodon |

Dicothodon moorensis |

|

||||

|

Pseudosaurillus sp. |

|

|||||

| Bicuspidon | Bicuspidon numerosus |

|

||||

|

Bothriagenys |

Bothriagenys mysterion |

|

||||

|

Primaderma |

Primaderma nessovi |

|

||||

|

Coniophis sp. |

|

|||||

Turtles

Indeterminate baenid remains present in the Mussentuchit Member.

| Turtles of the Cedar Mountain Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Member | Abundance | Description | Images |

|

Glyptops sp. |

|

Peripherals | ||||

|

Naomichelys sp. |

|

|||||

| gen. nov.[31] | sp. nov. |

|

||||

Amphibians

Indeterminate anuran remains present in the Mussentuchit Member.

| Amphibians of the Cedar Mountain Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Member | Abundance | Description | Images |

|

Albanerpeton cf. A. nexuosus |

|

| ||||

Bony fish

Indeterminate amiiform present in the Yellow Cat and Mussentuchit Members. Indeterminate neopterygion remains present in the Mussentuchit Member. Possible indeterminate pycnodontid remains present in the Mussentuchit Member. Possible indeterminate lepisosteid remains present in the Mussentuchit Member.

| Bony Fishes of the Cedar Mountain Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Member | Abundance | Description | Images |

|

Semionotus? sp. |

|

| ||||

|

C. kempae[32] |

|

|||||

|

C. kirklandi |

|

|||||

|

C. molossus |

|

|||||

Cartilaginous fish

A new genus and species of orectolobid present in the Mussentuchit Member.

| Cartilaginous Fishes of the Cedar Mountain Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Member | Abundance | Description | Images |

|

Hybodus sp. |

|

| ||||

|

Polyacrodus |

Polyacrodus parvidens |

|

||||

|

Lissodus sp. |

|

|||||

|

Ischyrhiza sp. |

|

|||||

|

Pseudohypolophus |

Pseudohypolophus sp. |

|

||||

|

cf. Baibisha |

New species |

|

||||

|

Indeterminate |

|

|||||

Mammaliaformes

New genus and species of pappotheriid present in the Mussentuchit Member. Indeterminate genus and species of picopsid present in the Mussentuchit Member.

| Mammals of the Cedar Mountain Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Member | Abundance | Description | Images |

|

Ameribaatar zofiae |

|

An unspecified multituberculate. | ||||

|

Astroconodon delicatus |

|

A predatory triconodont with a debate on whether it was fully terrestrial or semiaquatic. | ||||

|

Bryceomys intermedius |

|

An unspecified multituberculate, probably a cimolodont. | ||||

|

Cedaromys bestia |

|

|||||

|

Cedaromys parvus |

|

|||||

|

Cifelliodon wahkermoosuch |

|

|||||

|

Corviconodon |

Corviconodon utahensis |

|

||||

|

Dakotadens[34] |

Dakotadens pertritus |

|

||||

|

Janumys erebos |

|

|||||

|

Jugulator amplissimus |

|

|||||

|

Kokopellia |

Kokopellia juddi |

|

Possible metatherian |

|||

|

Paracimexomys perplexus |

|

|||||

|

Paracimexomys robisoni |

|

|||||

|

Spalacolestes |

Spalacolestes cretulablatta |

|

||||

|

Spalacolestes inconcinnus |

|

|||||

|

Spalacotheridium |

Spalacotheridium noblei |

|

||||

See also

- List of dinosaur-bearing rock formations

References

- Stokes (1944).

- Kowallis, et al. (1998).

- Stokes (1952).

- Aubrey (1998).

- Kirkland, et al. (1997b).

- Roca-Argemi and Nadon (2003).

- Kirkland and Madsen (2007).

- R. M. Joeckel, G. A. Ludvigson, A. Möller, C. L. Hotton, M. B. Suarez, C. A. Suarez, B. Sames, J. I. Kirkland and B. Hendrix (2019) Chronostratigraphy and Terrestrial Palaeoclimatology of Berriasian-Hauterivian Strata of the Cedar Mountain Formation, Utah, USA.Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 498.

- "Geological and Taphonomic Setting," DiCroce and Carpenter (2001). Page 186.

- "Depositional Setting," Tidwell, Carpenter, and Meyer (2001). Page 140.

- "Introduction," DiCroce and Carpenter (2001). Page 186.

- "Introduction," DiCroce and Carpenter (2001). Page 185.

- "Geological and Taphonomic Setting," DiCroce and Carpenter (2001). Page 187.

- Chure, et al. (2010).

- Carpenter (2006).

- Cifelli, et al. (1999).

- "Table 17.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 366.

- Carpenter, et al. (2008).

- "Table 17.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 365.

- "Table 17.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 364.

- Kinneer, Billy; Carpenter, Kenneth; Shaw, Allen (2016). ""Redescription of Gastonia burgei (Dinosauria: Ankylosauria, Polacanthidae), and description of a new species". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie". Abhandlungen. 282 (1): 37–80. doi:10.1127/njgpa/2016/0605.

- Scheetz, R. A.; Britt, B. B.; Higgerson, J. (2010). "A large, tall-spined iguanodontid dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous (Early Albian) basal Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (Supplement 2): 158A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.10411819.

- "Table 19.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 417.

- "Table 19.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 414.

- "Table 13.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 267.

- Royo-Torres, R.; Upchurch, P.; Kirkland, J.I.; DeBlieux, D.D.; Foster, J.R.; Cobos, A.; Alcalá, L. (2017). "Descendants of the Jurassic turiasaurs from Iberia found refuge in the Early Cretaceous of western USA". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 14311. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-14677-2. PMC 5662694. PMID 29085006.

- "Table 13.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 268.

- "Table 13.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 269.

- "Table 4.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 76.

- "Table 10.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 198.

- Brinkman, D.B., Scheetz, R.D., Jensen, C., Britt, B.B., and Ortiz, N., 2015, A basal baenid turtle provides insights into the aquatic fauna of the Early Cretaceous (Aptian) Cedar Mountain Formation of west-central Utah [abs.]: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, \ Abstracts and Program, p. 96.

- Frederickson J.A. and Cifelli R.L. (2016) New Cretaceous lungfishes (Dipnoi, Ceratodontidae) from western North America. Journal of Paleontology.

- Huttenlocker AD, Grossnickle DM, Kirkland JI, Schultz JA, Luo Z-X. 2018. Late-surviving stem mammal links the lowermost Cretaceous of North America and Gondwana. Nature Letters

- Cifelli, Richard L.; Cohen, Joshua E.; Davis, Brian M. (2016). "New tribosphenic mammals from the Mussentuchit Local Fauna (Cedar Mountain Formation, Cenomanian), Utah, USA". Palaeontologia Polonica. 67: 67–81. doi:10.4202/pp.2016.67_067.

Bibliography and further reading

- Aubrey, W.M. 1998. A newly discovered, widespread fluvial facies and unconformity marking the Upper Jurassic/Lower Cretaceous boundary, Colorado Plateau. Modern Geology, v. 22, p. 209-233.

- Carpenter, K., 2006, Assessing dinosaur faunal turnover in the Cedar Mountain Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of eastern Utah, USA. Ninth International Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems and Biota, Abstract and Proceedings Volume, p. 21-25.

- Carpenter, Kenneth; Bartlett, Jeff; Bird, John; Barrick, Reese (2008). "Ankylosaurs from the Price River Quarries, Cedar Mountain Formation (Lower Cretaceous), east-central Utah". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (4): 1089–1101. doi:10.1671/0272-4634-28.4.1089.

- Chure, Daniel; Britt, Brooks; Whitlock, John A.; Wilson, Jeffrey A. (2010). "First complete sauropod dinosaur skull from the Cretaceous of the Americas and the evolution of sauropod dentition". Naturwissenschaften. 97 (4): 379–91. doi:10.1007/s00114-010-0650-6. PMC 2841758. PMID 20179896.

- Cifelli, R. L., Nydam, R. L., Gardner, J. D., Weil, A., Eaton, J. G., Kirkland, J. I., and Madsen, S., 1999, Medial Cretaceous vertebrates from the Cedar Mountain Formation, Emery County, Utah: the Mussentuchit Local Fauna, in, Gillette, D., Vertebrate Paleontology in Utah. Utah Geological Survey Miscellaneous Publication 99-1, p. 219-242.

- Kirkland, J.I., Britt, B., Burge, D., Carpenter, K., Cifelli, R., DeCourten, F., Eaton, J., Hasiotis, S., and Lawton, T., 1997b, Lower to Middle Cretaceous dinosaur faunas of the Central Colorado Plateau: a key to understanding 35 million years of tectonics, sedimentology, evolution, and biogeography. Brigham Young University Geology Studies, v. 42, p. 69-103.

- Kirkland, J.I. and Madsen, S.K. 2007. The Lower Cretaceous Cedar Mountain Formation, eastern Utah: the view up an always interesting learning curve. Fieldtrip Guidebook, Geological Society of America, Rocky Mountain Section. 1-108 p.

- Kowallis, B. J.; Christiansen, E. H.; Deino, A. L.; Peterson, F.; Turner, C.E.; Kunk, M. J.; Obradovich, J. D. (1998). "The age of the Morrison Formation". Modern Geology. 22: 235–260.

- Roca-Argemi, X. and Nadon, G. C. 2003. The Buckhorn Conglomerate as the upper member of the Morrison Formation: new evidence from the type section, Cedar Mountain, Utah. Geological Society of America, Rocky Mountain Section, 55th Annual Meeting, Paper 14-1.

- Sanders, F.; Manley, K.; Carpenter, K. (2001). "Gastroliths from the Lower Cretaceous sauropod Cedarosaurus weiskopfae". In Tanke, Darren; Carpenter, Ken (eds.). Mesozoic Vertebrate Life: New Research Inspired by the Paleontology of Philip J. Currie. Indiana University Press. pp. 166–180. ISBN 0-253-33907-3.

- Shapiro, R.S.; Fricke, H.C.; Fox, K. (2009). "Dinosaur-bearing oncoids from ephemeral lakes of the Lower Cretaceous Cedar Mountain Formation, Utah". PALAIOS. 2 (4): 51–58. doi:10.2110/palo.2008.p08-013r.

- Stokes, W. L. 1944, Morrison and related deposits in the Colorado Plateau. Geological Society of America Bulletin v. 55, p. 951-992.

- Stokes, W.L. (1952). "Lower Cretaceous in the Colorado Plateau". American Association of Petroleum Geologists. 36: 1766–1776.

- Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. 861 pp. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.