Sauropelta

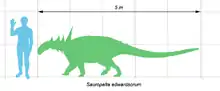

Sauropelta (/ˌsɔːroʊˈpɛltə/ SAWR-o-PEL-tə; meaning 'lizard shield') is a genus of nodosaurid dinosaur that existed in the Early Cretaceous Period of North America. One species (S. edwardsorum) has been named although others may have existed. Anatomically, Sauropelta is one of the most well-understood nodosaurids, with fossilized remains recovered in the U.S. states of Wyoming, Montana, and possibly Utah. It is also the earliest known genus of nodosaurid; most of its remains are found in a section of the Cloverly Formation dated to 108.5 million years ago.

| Sauropelta | |

|---|---|

| |

| Specimen AMNH 3036, fossil armor and tail in the American Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | †Ornithischia |

| Suborder: | †Ankylosauria |

| Family: | †Nodosauridae |

| Genus: | †Sauropelta Ostrom, 1970 |

| Type species | |

| †Sauropelta edwardsorum | |

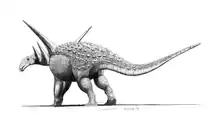

It was a medium-sized nodosaurid, measuring about 5.2 metres (17.1 ft) long. Sauropelta had a distinctively long tail which made up about half of its body length. Although its body was smaller than a modern black rhinoceros, Sauropelta was about the same mass, weighing in at about 1,500 kilograms (3,300 lb). The extra weight was largely due to its extensive covering of bony armor, including the characteristically large spines projecting from its neck.

Description

Sauropelta was a heavily built quadrupedal herbivore with a body length of approximately 5.2 m (17.1 ft).[1] In 2010 Gregory S. Paul estimated it at 6 meters (19.7 ft) and 2 tonnes (2.2 short tons).[2] Thomas Holtz gave a higher estimation of 7.6 meters (25 feet).[3] The skull was triangular when viewed from above, with the rear end wider than the tapering snout. One skull measured 35 centimeters (13.75 in) in width at its widest point, behind the eyes.[4] Unlike some other nodosaurids, the roof of the skull was characteristically flat, not domed. The roof of the skull was very thick and covered in flat, bony plates that are so tightly fused that there appear to be no sutures (boundaries) like the ones seen in Panoplosaurus, Pawpawsaurus, Silvisaurus, and many other ankylosaurs. This could also be an artifact of preservation or preparation. As in other ankylosaurs, thick triangular scutes projected from the postorbital bone, above and behind the eyes, as well as the jugal bone, below and behind the eyes.[4] More typically for nodosaurids, leaf-shaped teeth lined both upper and lower jaws, used for cutting plant material. The front end of the skull is unknown, but there would have been a sharp bony ridge (tomium) at the end of both upper and lower jaws, as seen in other ankylosaurs. This ridge probably would have supported a keratinous beak.[5]

The tail of Sauropelta was characteristically long and made up nearly half of the body length. One skeleton preserved forty caudal (tail) vertebrae, although some were missing, suggesting that the true number of caudal vertebrae may have exceeded fifty. Ossified tendons stiffened the tail along its length. Like other ankylosaurs, Sauropelta had a wide body, with a very broad pelvis and ribcage. The forelimbs were shorter than the hindlimbs, which resulted in an arched back, with the highest point over the hips. Its feet, limbs, shoulders, and pelvis were all very stoutly constructed and reinforced to support a great deal of weight. American paleontologist Ken Carpenter estimated the mass of S. edwardsorum at 1,500 kilograms (3,300 lb).[1]

Like other nodosaurids, Sauropelta was covered in armor formed from bony masses embedded in the skin (osteoderms). The discovery of a skeleton with the body armor preserved in situ allowed Carpenter and other scientists to accurately describe this protection. Two parallel rows of domed scutes ran down the top of the neck, along the anteroposterior axis (front to back). On the upper surface of the back and tail, the skin was covered in small, bony nodules (ossicles), which separated larger conical scutes arranged in parallel rows along the mediolateral axis (side to side). Over the hips, the ossicles and larger domed plates were interlocked very tightly to form a structure called a sacral shield.[1] This shield is also found in ankylosaurs like Polacanthus and Antarctopelta.[5][6] Large, pointed spines lined the sides of the neck, increasing in size towards the shoulders, and then decreasing in size again along the side of the body until they stopped just before the hips. Behind the hips, flat triangular plates lined the tail on both sides, pointing laterally (outwards) and decreasing in size towards the end of the tail. Carpenter originally described the cervical (neck) spines and caudal plates as belonging to a single row on each side, although more recently he and Jim Kirkland reconstructed them in two parallel rows on each side, one above the other. The upper row of cervical spines pointed backwards and upwards (posterodorsally), while the lower row pointed backwards and outwards (posterolaterally). The bases of each pair of cervical spines and each pair of caudal plates were fused together, greatly restricting mobility in both the neck and upper tail.[4]

Classification and systematics

Since John Ostrom first described Sauropelta in 1970, it has been recognized as a member of the family Nodosauridae.[7] The nodosaurids, along with the family Ankylosauridae, belong within the infraorder Ankylosauria. Nodosaurids are characterized by certain features of the skull, including the mandible (lower jaw), which curves downwards at the end. Overall, nodosaurids had narrower snouts than the ankylosaurids, and also lacked the heavy ankylosaurid tail clubs.[8] Nodosaurids, like ankylosaurids, are found in North America, Asia, and Europe.

While the systematics (evolutionary relationships) of nodosaurids have not been firmly established, the genera Sauropelta, Silvisaurus and Pawpawsaurus are sometimes considered to be basal to geologically younger nodosaurids like Panoplosaurus, Edmontonia, and Animantarx.[5][9] In a 2001 analysis, Carpenter included the former three genera in a sister clade to a group containing the latter three, although he found that Panoplosaurus could belong to either clade, depending which taxa and characters were chosen.[10]

Discovery and naming

In the early 1930s, famed dinosaur hunter and paleontologist Barnum Brown collected the holotype specimen of Sauropelta (AMNH 3032, a partial skeleton) from the Cloverly Formation in Big Horn County, Montana. The locality is inside the Crow Indian Reservation. Brown also discovered two other specimens (AMNH 3035 and 3036). The latter is one of the best-preserved nodosaurid skeletons known to science, includes a large amount of in situ armor, and is on display in the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. AMNH 3035 preserves the cervical armor and most of a skull, missing only the end of the snout. Expeditions in the 1960s led by the equally renowned John Ostrom of Yale University's Peabody Museum of Natural History recovered additional incomplete specimens from the Cloverly. In 1970, Ostrom coined the genus Sauropelta to include remains discovered by both expeditions. Derived from the Greek σαυρος (sauros) ('lizard') and πελτε (pelte) ('shield'), this name is a reference to its bony armor.[7] Although Ostrom originally named the species S. edwardsi, nomenclaturist George Olshevsky corrected the spelling to S. edwardsorum in 1991 to conform to Latin grammar rules.[11]

Despite the naming of Sauropelta two years earlier, confusion arose in 1972 when the name "Peltosaurus" was inadvertently published as the caption of a photograph of AMNH 3036.[12] Although Brown never published a name or description for the remains which are now known as Sauropelta edwardsorum, "Peltosaurus" was the name he informally used in lectures and museum exhibits. However, the name Peltosaurus was preoccupied by a genus of North American lizard from an extinct branch of the modern family Anguidae (the alligator lizards and the legless glass lizards) and is no longer used to refer to the dinosaur.[13]

In 1999, Carpenter and colleagues described material of a large nodosaurid from Utah, discovered in a member of the Cedar Mountain Formation called the Poison Strip Sandstone, which is contemporaneous with the Cloverly Formation. He originally referred it to Sauropelta as a possible new species, but it was never named.[14] In more recent publications, Carpenter no longer refers the Poison Strip animal to Sauropelta, only to the family Nodosauridae.[15]

Other recent, but undescribed, discoveries include a complete skull from the Cloverly of Montana[16] and a huge fragmentary skeleton from the Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah.[17] These discoveries have been published only as abstracts for the annual Society of Vertebrate Paleontology conference, and may or may not prove to belong to S. edwardsorum or even Sauropelta when formally published.

Footprint discoveries

In 1932, Charles Mortram Sternberg reported the presence of the footprints of a large, four-footed dinosaur from Lower Cretaceous rocks in British Columbia, Canada. He described a new ichnogenus and species for these tracks, Tetrapodosaurus borealis, and attributed them to ceratopsians. However, in 1984 paleontologist Kenneth Carpenter re-examined the British Columbian Tetrapodosaurus prints and argued that they were made by ankylosaurs rather than ceratopsians. Specifically, Carpenter concluded that these were probably the footprints of Sauropelta. Five years later, large numbers of Tetrapodosaurus tracks were discovered at the Smoky River Coal Mine near Grande Cache, Alberta. This site is considered the most important ankylosaur track site in the world.[18]

Paleoecology

Sauropelta was one of the earliest known nodosaurids. All specimens of S. edwardsorum were recovered from the Little Sheep Mudstone section of the Cloverly Formation in Wyoming and Montana, which has been dated to 108.5 million years ago, during the Early Cretaceous.[19][20] Sauropelta lived in wide floodplains around rivers that drained into the shallow inland sea to the north and east, carrying sediment eroded from the low mountains to the west. Periodic flooding of these rivers covered the surrounding plains with new muddy sediments, creating the Cloverly Formation and burying the remains of many animals, some of which would be fossilized. At the end of Cloverly times, the shallow sea would expand to cover the entire region and would eventually split North America completely in half, forming the Western Interior Seaway.[21] Abundant fossil remains of coniferous trees suggest that these plains were covered in forests.[7] Grasses would not evolve until later in the Cretaceous, so Sauropelta and other Early Cretaceous dinosaurian herbivores browsed from a variety of conifers and cycads.[22] Nodosaurids like Sauropelta had narrow snouts, an adaptation seen today in animals that are selective browsers as opposed to the wide muzzles of grazers.[8]

While Sauropelta was an important part of the Cloverly herbivore guild, the most abundant herbivorous dinosaur of the time was the large ornithopod Tenontosaurus. The smaller ornithopod Zephyrosaurus, rare titanosaur sauropods, and an unknown type of ornithomimosaur also lived alongside Sauropelta. The dromaeosaurid theropod Deinonychus fed upon some of these herbivores, and the sheer number of Deinonychus teeth scattered throughout the formation are a testament to its abundance.[7][21] Microvenator, a small basal oviraptorosaur, hunted smaller prey,[7][21] while the apex predators of the Cloverly was the large allosauroid theropod Acrocanthosaurus.[23] Lungfish, triconodont mammals, and several species of turtles lived in the Cloverly, while crocodilians prowled the rivers, lakes, and swamps, providing evidence of a year-round warm climate.[7][21] The Late Jurassic fauna dominated by allosauroids, stegosaurs, and many varieties of huge sauropods gave way by Cloverly times to an Early Cretaceous fauna in which dromaeosaurs, ornithopods, and nodosaurs like Sauropelta were predominant. After the Cloverly ended, a large wave of Asian animals, including tyrannosaurids, ceratopsians, and ankylosaurids would disperse into western North America, forming the mixed fauna seen throughout the Late Cretaceous.[4]

See also

References

- Carpenter, Kenneth. (1984). "Skeletal reconstruction and life restoration of Sauropelta (Ankylosauria: Nodosauridae) from the Cretaceous of North America". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 21 (12): 1491–1498. doi:10.1139/e84-154.

- Paul, Gregory S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. pp. 236. ISBN 9780691137209.

- Holtz, Thomas R. (2012). "Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages" (PDF).

- Carpenter, Kenneth; Kirkland, James I. (1998). "Review of Lower and Middle Cretaceous Ankylosaurs from North America". In Lucas, Spencer G.; Kirkland, James I; Estep, J.W. (eds.). Lower and Middle Cretaceous Ecosystems. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 14. pp. 249–270.

- Vickaryous, Matthew K.; Maryanska, Teresa; Weishampel, David B. (2004). "Ankylosauria". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (Second ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 363–392.

- Salgado, Leonardo; Gasparini, Zulma. (2006). "Reappraisal of an ankylosaurian dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of James Ross Island (Antarctica)". Geodiversitas. 28 (1): 119–135.

- Ostrom, John H. (1970). "Stratigraphy and paleontology of the Cloverly Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of the Bighorn Basin area, Wyoming and Montana". Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History. 35: 1–234.

- Carpenter, Kenneth. (1997). "Ankylosauria". In Currie, Philip J.; Padian, Kevin (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 16–17.

- Hill, Robert V.; Witmer, Lawrence M.; Norell, Mark A. (2003). "A new specimen of Pinacosaurus grangeri (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia: Ontogeny and Phylogeny of Ankylosaurs" (PDF). American Museum Novitates. 3395: 1–29. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2003)395<0001:ANSOPG>2.0.CO;2.

- Carpenter, Kenneth. (2001). "Phylogenetic analysis of the Ankylosauria". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 455–483.

- Olshevsky, George. (1991). A Revision of the Parainfraclass Archosauria Cope, 1869, Excluding the Advanced Crocodylia. Mesozoic Meanderings No. 2. San Diego: Publications Requiring Research. p. 196pp.

- Glut, Donald F. (1972). The Dinosaur Dictionary. Secaucus: Citadel Press. p. 217pp.

- Chure, Daniel J.; McIntosh, John S. (1989). A Bibliography of the Dinosauria (Exclusive of the Aves), 1677-1986. Paleontology Series 1. Grand Junction: Museum of Western Colorado. p. 226pp.

- Carpenter, Kenneth; Kirkland, James I.; Burge, Donald; Bird, John (1999). "Ankylosaurs (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) of the Cedar Mountain Formation, Utah, and their stratigraphic distribution". In Gillette, David (ed.). Vertebrate Paleontology of Utah. Utah Geological Survey Miscellaneous Publication 99-1. pp. 244–251.

- Carpenter, Kenneth. (2006). "Assessing dinosaur faunal turnover in the Cedar Mountain Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of Eastern Utah, USA". In Barrett, Paul M.; Evans, S.E (eds.). Ninth International Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems and Biota. London: Natural History Museum. pp. 21–25.

- Parsons, William L.; Parsons, Kristen M. (2001). "Description of a new skull of Sauropelta cf. S. edwardsi Ostrom, 1970 (Ornithischia: Ankylosauria)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (Supplement to 3 - Abstracts of Papers, 61st Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology): 87A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2001.10010852.

- Warren, David; Carpenter, Kenneth. (2004). "A large nodosaurid ankylosaur from the Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (Supplement to 3 - Abstracts of Papers, 64th Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology): 126A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2004.10010643.

- McCrea, Richard T. 2000. Vertebrate palaeoichnology of the lower cretaceous (lower Albian) gates formation of Alberta.

- Kirkland, James I.; Britt, Brooks; Burge, Donald L.; Carpenter, Kenneth; Cifelli, Richard; DeCourten, Frank; Eaton, Jeffrey; Hasiotis, Steven; Lawton, Timothy (1997). "Lower to Middle Cretaceous Dinosaur faunas of the central Colorado Plateau: a key to understanding 35 million years of tectonics, sedimentology, evolution, and biogeography". Brigham Young University Geology Studies. 42 (II): 69–103.

- Kirkland, J.I.; Alcalá, L.; Loewen, M.A.; Espílez, E.; Mampel, L.; Wiersma, J.P. (2013). Butler, Richard J. (ed.). "The Basal Nodosaurid Ankylosaur Europelta carbonensis n. gen., n. sp. from the Lower Cretaceous (Lower Albian) Escucha Formation of Northeastern Spain". PLoS ONE. 8 (12): e80405. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080405. PMC 3847141. PMID 24312471.

- Maxwell, W. Desmond. (1997). "Cloverly Formation". In Currie, Philip J.; Padian, Kevin (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 128–129.

- Prasad, Vandana; Strömberg, Caroline A.E.; Alimohammadian, Habib; Sahni, Ashok. (2005). "Dinosaur coprolites and the early evolution of grasses and grazers". Science. 310 (5751): 1177–1180. doi:10.1126/science.1118806. PMID 16293759.

- D'Emic, Michael D.; Melstrom, Keegan M.; Eddy, Drew R. (2012). "Paleobiology and geographic range of the large-bodied Cretaceous theropod dinosaur Acrocanthosaurus atokensis". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 333–334: 13–23. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.03.003.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sauropelta. |

- Entries in Online Collections Database at the American Museum of Natural History:

- Entry for Nodosauridae on Tree of Life, including modern restoration of Sauropelta armor