Chesterfield, Missouri

Chesterfield is a city in St. Louis County, Missouri, United States, and a western suburb of St. Louis. As of the 2010 census, the population was 47,484, making it the state's fourteenth-largest city. The broader valley of Chesterfield was originally referred to as "Gumbo Flats", derived from its soil, which though very rich and silty, became like a gumbo when wet.

Chesterfield, Missouri | |

|---|---|

| City of Chesterfield | |

From top left: Butterfly House, Faust Park, Residential area, Old Chesterfield | |

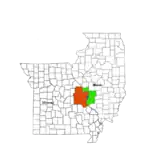

Location of Chesterfield, Missouri | |

| Coordinates: 38°39′12″N 90°33′15″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Missouri |

| County | St. Louis |

| Incorporated | 1988 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Bob Nation[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 33.65 sq mi (87.14 km2) |

| • Land | 31.88 sq mi (82.56 km2) |

| • Water | 1.77 sq mi (4.58 km2) |

| Elevation | 479 ft (146 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 47,484 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 47,538 |

| • Density | 1,491.34/sq mi (575.81/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Zip code | 63005, 63017 |

| Area code(s) | 314, 636 |

| FIPS code | 29-13600[5] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0755881[6] |

| Website | www |

| [7] | |

Geography

Chesterfield is located approximately 25 miles (40 km) west of St. Louis. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 33.52 square miles (86.82 km2), of which 31.78 square miles (82.31 km2) is land and 1.74 square miles (4.51 km2) is water.[8]

Portions of Chesterfield are located in the floodplain of the Missouri River, now known as Chesterfield Valley, formerly as Gumbo Flats. This area was submerged during the Great Flood of 1993; higher levees built since then have led to extensive commercial development in the valley. Chesterfield Valley is the location of Spirit of St. Louis Airport, used for corporate aviation, as well as the longest outdoor strip mall in America.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1990 | 37,991 | — | |

| 2000 | 46,802 | 23.2% | |

| 2010 | 47,484 | 1.5% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 47,538 | [4] | 0.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census | |||

According to the 2007–2011 American Community Survey estimate, the median income for a household in the city was $95,006, and the median income for a family was $88,568. Males had a median income of $94,322 versus $54,934 for females. The per capita income for the city was $51,725. About 1.7% of families and 4.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 1.7% of those under age 18 and 3.3% of those age 65 or over.[9]

2010 census

As of the census[3] of 2010, there were 47,484 people, 19,224 households, and 13,461 families living in the city. The population density was 1,494.1 inhabitants per square mile (576.9/km2). There were 20,393 housing units at an average density of 641.7 per square mile (247.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 86.5% White, 2.6% African American, 0.2% Native American, 8.6% Asian, 0.7% from other races, and 1.4% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.8% of the population.

There were 19,224 households, of which 29.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 62.2% were married couples living together, 5.9% had a female householder with no husband present, 2.0% had a male householder with no wife present, and 30.0% were non-families. 26.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.42 and the average family size was 2.94.

The median age in the city was 46.6 years. 22.3% of residents were under the age of 18; 5.7% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 19.5% were from 25 to 44; 32.5% were from 45 to 64; and 20.1% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 47.8% male and 52.2% female.

2000 census

As of the census[5] of 2000, there were 46,802 people, 18,060 households, and 13,111 families living in the city. The population density was 1,485.4 people per square mile (573.5/km2). There were 18,738 housing units at an average density of 594.7 per square mile (229.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 92.30% White, 0.86% African American, 0.12% Native American, 5.56% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 0.39% from other races, and 0.74% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.55% of the population.

There were 18,060 households, out of which 33.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 65.5% were married couples living together, 5.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27.4% were non-families. 23.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.53 and the average family size was 3.03.

In the city the population was spread out, with 24.6% under the age of 18, 5.9% from 18 to 24, 25.0% from 25 to 44, 29.7% from 45 to 64, and 14.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.2 males.

History

Ancient history

Present-day Chesterfield is known to have been a site of Native American inhabitation for thousands of years. A site in western Chesterfield containing artwork and carvings has been dated as 4,000 years old.[10] A Mississippian site, dated to around the year 1000, containing the remains of what have been identified as a market and ceremonial center, is also located in modern Chesterfield.[10]

Historical communities

The present-day city of Chesterfield is made up of several smaller historical communities, including:

- Bellefontaine (French for "beautiful spring"), or as the locals called it, "Hilltown", dates to about 1837 with the arrival of August Hill. The first post office was established as Bellemonte ("beautiful mountain") in 1851. Eighteen years later, in 1869, the town and post office name were both changed to Bellefontaine. Rinkel's Market was a familiar landmark for years, at the intersection of present-day Olive Boulevard and Chesterfield Parkway (where Charlie Gitto's from The Hill is now).

- The town of Lake started out as "Hog Hollow," in about 1850. The post office was established as Hog Hollow in 1871, but a year later the town's name was changed to what some thought was the more suitable name of Lake. Zierenberg's General Merchandise and Saloon (built around 1880) was a well-known landmark at the 18-mile marker on Olive Street Road. The original structure was destroyed by fire in 1918. It was replaced by the existing structure on the same site (Olive Boulevard and Hog Hollow Road).

- Gumbo is located in the valley at the present intersection of Chesterfield Airport Road and Long Road. A notable landmark (until it was razed in 1998) was the old Twenty Five Mile House - so named because of its distance from downtown St. Louis. Gumbo's name derived from its soil, which though very rich and silty, when wet became gumbo mud. A substance very similar to gravel was made from Gumbo mud and used for streets and sidewalks in Forest Park during the 1904 World's Fair. Gumbo's post office operated from 1882 to 1907.

- Monarch (earlier called Atherton, then Eatherton) was one of the settlements that sprang up along the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific rail line when it came through the valley in the late 1870s. William Sutton's General Store stood on the northwest corner of Eatherton and Centaur Roads. Their post office operated from 1895 to 1907, when the mail was transferred to Chesterfield. A well-known residence in Monarch was named "The Shadows"; it still survives, with a commanding view from its bluff site.

- Bonhomme had a colorful life. The name is French for "good man." This small community, at the extreme western end of Olive Street Road, was close to the Howell's Ferry landing. It had a blacksmith shop, grist mill, store, post office and Fenn's saw mill; but it was all washed away in the late 19th century by the Missouri River. Bonhomme was a popular name in St. Louis County; with Bonhomme streets, roads, creeks, churches and townships still so-named. However, this Bonhomme is the only one that ever had its own post office.

1967 tornado

On January 24, 1967, a violent F4 tornado ripped a 21-mile (34 km) path of destruction across St. Louis County. It was the fourth-worst tornado to hit the St. Louis metro area and the most recent F4 tornado to hit the city. The tornado developed near the Chesterfield Manor nursing home and then moved through River Bend Estates and across northeast St. Louis County.[11]

Incorporation as Chesterfield

For many years, "Chesterfield" was an all-inclusive place-name for a vast, unincorporated sub-region of western St. Louis County (called "West County" by metro area residents) containing the unincorporated historical communities listed above, plus areas now incorporated as cities of their own (e.g., Ballwin). Police and fire protection in the community were fragmented and sporadic, the former provided by St. Louis County. As the population grew, Chesterfield Mall and other retail and commercial real estate developments sprang up; however, many residents were concerned about the lack of quality public services, and that the municipal sales tax benefited the county instead of the community.

An organization was formed calling itself the "Chesterfield Incorporation Study Committee." Headed by its president, John A. Nuetzel (himself a former president of the River Bend Association, a zoning watchdog group), the members "passed the hat" at neighborhood meetings, engaged legal help, drew up metes and bounds, and forced several failed public votes for incorporation. After a number of years, in 1988, The City of Chesterfield was finally established by its residents, and has thrived as perhaps West County's premier residential, business, retail, and transportation center.

Flood of 1993

On July 30, 1993, the levee that protected Gumbo Flats (now known as the Chesterfield Valley) from the Missouri River failed.[12] This was the first time the levee had failed since 1935.[13] The town was told to evacuate, and the whole area of Gumbo Flats was flooded by feet of water. Today, the area has become the Chesterfield Commons retail area.[12]

Transportation

Highways and major roads

Interstate 64 (locally referred to as "Highway 40") runs East-West through Chesterfield. There are seven exits serving the city (numbers 14-21). Missouri Route 340 (a.k.a., Olive Blvd.) runs on East-West though much of Chesterfield, before turning Southwest near the I-64 Interchange; its name changes to Clarkson Road south of this junction. Missouri Route 141 runs along the eastern border between Chesterfield and Town and Country. Route 141's northern terminus was, until recently, located in Chesterfield at Olive Blvd. The Missouri Department of Transportation (MoDOT) and St. Louis County Department of Highways and Traffic (DHT) began construction of Route 141 in Chesterfield in 2009.[14] MoDOT expanded Route 141 between just south of Ladue Road (Route AB) to Olive Boulevard (Route 340). DHT extends Route 141 from Olive Road to the Page Avenue Extension (Route 364) at the Maryland Heights Expressway.[15]

Public transportation

Public transportation is provided by Metro and connects Chesterfield to many other portions of Greater St. Louis by numerous bus routes.[16]

Air

Spirit of St. Louis Airport is located in the Chesterfield Valley; the airport is owned by St. Louis County.[17]

Rail

Central Midland Railway (CMR), a division of Progressive Rail Inc. of Minnesota, provides regular freight rail service to industrial customers located in the Chesterfield Valley. CMR operates the far eastern segment of the former Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railway's St. Louis to Kansas City main line that was constructed in 1870.[18] The active portion of the former CRI&P line runs from the north side of St. Louis, where it connects with the Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis and Union Pacific Railroad, and now terminates in Union, Missouri.[19] A primary rail customer in Chesterfield is a RockTenn (formerly Smurfit Stone) corrugated packaging plant which is located on a spur track that extends from the main track northward along the east end of the runway of the Spirit of St. Louis Airport. RockTenn typically receives inbound shipments of corrugated paper.[20]

Education

Primary and secondary schools

Chesterfield has a number of elementary and middle schools, plus multiple high schools. The Rockwood School District serves the western portions of the city, while the Parkway School District serves the east. Chesterfield's sole private high school, Barat Academy, is located on the former Chesterfield campus of Gateway Academy, a former private elementary school. The city also has four private elementary schools: Chesterfield Day School, Chesterfield Montessori School, Ascension School, and Incarnate Word School.

Colleges and universities and trade schools

Logan College of Chiropractic offers undergraduate and graduate level courses on Chiropractic, Pre-Chiropractic, Sport Science and Rehabilitation medicine.[21]

Public libraries

St. Louis County Library Samuel C. Sachs Branch is in Chesterfield.[22]

Economy

Reinsurance Group of America, Dierbergs, Kellwood, Amdocs, Aegion and Broadstripe have their headquarters in Chesterfield.[23] Chesterfield has three malls, two of which are outlet malls as well as a strip mall called the Chesterfield Commons.[24]

Top employers

According to the City's 2013 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[25] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | St. Luke's Hospital | 3,447 |

| 2 | Parkway School District | 1,195 |

| 3 | Bayer | 1,011 |

| 4 | Delmar Gardens Enterprises | 913 |

| 5 | Reinsurance Group of America | 780 |

| 6 | Dierbergs Markets | 485 |

| 7 | Amdocs | 455 |

| 8 | Mercy Health | 430 |

| 9 | McBride & Son Companies | 400 |

| 10 | MOHELA | 379 |

Attractions

Faust Park contains an updated playground, historical village, walking trail, carousel, and "The Butterfly House",[26] which opened in 1998. A nearby giant cement butterfly sculpture by Bob Cassilly was dedicated in 1999.

The City has several recreation facilities including the Chesterfield Amphitheater, the Chesterfield Valley Athletic Complex, and the Chesterfield Family Aquatic Center.[27]

Notable people

- Michael Avenatti, American attorney and entrepreneur, moved to Chesterfield as a child and graduated from Parkway Central High School.[28]

- David Freese, third baseman for Los Angeles Angels, 2011 NLCS MVP, 2011 World Series MVP with the St. Louis Cardinals

- Ryan Howard, Philadelphia Phillies first baseman, 2005 NL Rookie of the Year, 2006 NL MVP

- Clayton Keller, NHL hockey forward for the Arizona Coyotes

- Luke Kunin, NHL hockey player for the Minnesota Wild

- Al Lowe, video game designer best known for the Leisure Suit Larry series of games.

- Jeremy Maclin, former Missouri Tigers wide receiver, former wide receiver for the Philadelphia Eagles,Kansas City Chiefs, and Baltimore Ravens

- Davis Payne, former head coach of the St. Louis Blues.

- Max Scherzer, MLB pitcher for the Washington Nationals

- Paul Stastny, center for the Winnipeg Jets of National Hockey League, Chaminade College Preparatory School alumnus

- Yan Stastny, center for the Thomas Sabo Ice Tigers of the Deutsche Eishockey Liga, Chaminade College Preparatory School alumnus.

- Jim Talent, former of the United States Senate, U.S. House of Representatives, and Missouri House of Representatives

- Scott Van Slyke, outfielder for Los Angeles Dodgers.

- Adam Wainwright, MLB pitcher for St. Louis Cardinals.

- Kurt Warner, former NFL quarterback for St. Louis Rams and Arizona Cardinals, 1999, 2001 NFL MVP, 2000 Super Bowl MVP.

References

- "Mayor's Office". Chesterfield, Missouri. City of Chesterfield, Missouri. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2012-01-25. Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-04-05. Retrieved 2013-11-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Mary Shapiro. "New book uncovers Chesterfield's ancient past : Sj". Stltoday.com. Retrieved 2013-04-13.

- "January 24th 1967 F4 Tornado St. Louis County". Crh.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2013-04-13.

- Johnson, Frank (15 July 2013). "Flood of 1993: How Gumbo Flats Became the Chesterfield Valley". Patch. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- "Flood of 93". Chesterfield, Missouri. City of Chesterfield, Missouri. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- "Route 141 Improvement Project (Ladue to Olive)". MoDOT. Archived from the original on 2005-02-28. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- "Page to Olive Connector Study". St. Louis County Department of Highways and Traffic. Retrieved 2008-10-15.

- "Metro Transit - Saint Louis". Metro St. Louis. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- FAA Airport Form 5010 for SUS PDF, effective 2007-07-05

- "Central Midland Railway CMR". Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- "Where We Go". Progressive Rail Inc. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- Brown, Lisa (January 25, 2011). "Rock-Tenn's bid to buy Smurfit-Stone means loss of HQ". St. Louis Post Dispatch. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- "Logan Academic Programs". Logan University. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- "Samuel C. Sachs Branch Archived 2009-09-30 at the Wayback Machine." St. Louis County Library. Retrieved on August 18, 2009.

- "Contact Us Archived 2010-03-06 at the Wayback Machine." Broadstripe. Retrieved on March 5, 2010.

- "Shopping and Dining". Chesterfield, Missouri. City of Chesterfield, Missouri. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for year ending December 31, 2013". Chesterfield, Missouri. City of Chesterfield, Missouri. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- "Butterfly House". Missouribotanicalgarden.org. Retrieved 2013-04-13.

- "Recreation Facilities". Chesterfield, Missouri. City of Chesterfield, Missouri. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- Holleman, Joe (2018-03-08). "Porn star Stormy Daniels' lawyer graduated from Parkway Central". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

.jpg.webp)

_(cropped).jpg.webp)