Chitral (princely state)

Chitral (or Chitrāl) (Urdu: چترال and ریاست چترال) was a princely state in alliance with British India until 1947, then a princely state of Pakistan until 1969.[1] The area of the state now forms the Chitral District of the Malakand Division, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan.

State of Chitral ریاست چترال | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1320–1969 | |||||||||

State flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

| Status | Princely state in alliance with British India | ||||||||

| Capital | Chitral Town | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Mehtar | |||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1320 | ||||||||

| 1320 | |||||||||

| 1571 | |||||||||

| 1885 | |||||||||

| 1919 | |||||||||

| 1969 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 14,850 km2 (5,730 sq mi) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan | ||||||||

| Chitral | |

|---|---|

| Princely state of Pakistan | |

| 14 August 1947–28 July 1969 | |

Flag | |

Map of Pakistan with Chitral highlighted | |

| Capital | Chitral |

| • Type | Monarchy |

| History | |

• Established | 14 August 1947 |

• Disestablished | 28 July 1969 |

|

| This article is part of the series |

| Former administrative units of Pakistan |

|---|

Location and demographics

The capital city of the former state was Chitral Town, which is situated on the west bank of the Chitral (or Kunar River) at the foot of Tirich Mir which at 7,708 m (25,289 ft) is the highest peak of the Hindu Kush. The borders of the state were seldom stable and fluctuated with the fortunes of Chitral's rulers, the Mehtars.[2] The official language of the state was Persian, a legacy of the adaptation policy of the early Delhi Sultanate and Mughal times. The general population of the state was mainly of the Kho people, who spoke Khowar, a Dardic language in the Indo-Aryan group. The Khowar language is also spoken in parts of Yasin, Gilgit and Swat.

History

Very little is known about the early history of Chitral. The country has historically been divided between two ethnic groups. The people of the upper part are called Kho; Khowar is their language. Those living in the lower part are called Chitrari. The two people shared many common cultural traits, yet they have long been distinct peoples. On the basis of this ethnic division, the country has, most of the time, remained divided into two principalities. Old traditions have saved names of some local rulers like Sumalik and Bahman in the upper part, and Bula Sinhg and Raja Wai in the lower part. These were probably local chiefs, with small areas under them. Oral traditions tell of this region being ruled by great neighboring empires like Mongol and Iran in the distant past. From 1320 to 1698 it was ruled by the Mongol Dynasty.

During the last years of the seventeenth century, the ancestor of the Katoor Dynasty overthrew the Mongol Dynasty. The head of the family, Möngke Khan-I became Mehtar, or king, of the small kingdom. The entire region that now forms the Chitral District was a fully independent monarchy until 1885, when the British negotiated a subsidiary alliance with its hereditary ruler, the Mehtar, under which Chitral became a princely state, still sovereign but subject to the suzerainty of the British Indian Empire. In 1895 the British agent in Gilgit, Sir George Scott Robertson was besieged in Chitral Fort for 48 days, and was finally relieved by two British Forces, one marching from Gilgit and the other from Nowshera. After 1895, the British hold became stronger, but the internal administration remained in the hand of the Mehtar. In 1947 India was partitioned and Chitral opted to accede to Pakistan. After accession, it gradually lost its autonomy, finally becoming an administrative district of Pakistan in 1969.[3]

The royal family of Chitral

The ruling family of Chitral was the Kator dynasty, founded by Muhtaram Shah Kator (1700-1720), which governed Chitral until 1969, when the Government of Pakistan took over.[4] During the reign of Mehtar Aman ul-Mulk, known as Lot (Great) Mehtar, the dynasty's sway extended from Asmar in the Kunar Valley of Afghanistan to Punial in the Gilgit Valley.[5] Tribes in Upper Swat, Dir, Kohistan and Kafiristan (present day Nuristan), paid tribute to the Mehtar of Chitral.

The ruler's title was Mitar which is pronounced as Mehtar by outsiders. Every son of the sitting Mehtar aspired for the throne, and bloody wars of accession were common. Sons of the sitting Mehtar ruled in the provinces and were also titled as Mitar, while other male relatives of the Mehtar were called Mitarjao. Aman ul-Mulk adopted the Persian style Shahzada for his sons, and the style prevailed then on. The word Khonza (meaning princess in the Khowar language) was reserved for female members of the Mehtars family.

The ruling family of Chitral traces its descent from a wandering Sufi mystic, Baba Ayub. Baba Ayub arrived in Chitral and married the daughter of the ruler Shah Raees, a supposed descendant of Alexander the Great. The grandson of this marriage founded the present Katoor dynasty. Accordingly, the family actually owes its fortunes to Sangin Ali, sometime minister to a Raees ruler of Chitral, during the seventeenth century. After his death his two sons, Muhammad Baig and Muhammad Raees held important positions in the state. Muhammad Baig had six sons who seized power, ousting the Rais ruler sometimes in the early years of the eighteenth century. The eldest of the brothers, Muhtaram Shah Katur I, became the ruler, establishing a new ruling dynasty over the state. The present ruling dynasty descends from Shah Afzal I, the second of son of Muhtaram Sha I. But that was not the end of the Rais dynast,y who had their base of power in neighboring Badakhshan. They made a number of attempts to regain the throne of Chitral and were successful for a brief period. Rais threat came to end but there were other troubles for the Katurs. Descendants of Shah Khushwaqt, the second brother of Muhtaram Shah, had established another principality in the upper Chitral also including the Ghizer and Yasin valleys. Frequent wars took place between the two principalities, and the Katurs lost their entire area to the powerful Khushwaqt ruler, Khairul Lah, in 1770. For more than 20 years the Katur family had to live in exile in Dir and other neighboring areas. Katur rule was finally restored in 1791 after the death of Khairul Lah in the battle of Urtsun.

Muhtaram Shah Katur II

He was the grandson of Katur I. Muhtaram Sha II and his brother Shah Nawaz Khan had a long struggle with Khairul Lah. After killing Khairul Lah, Sha Nawaz Khan became the ruler but was replaced by Muhtaram Shah II after a rule of six years. Muhtaram Sha II was an able statesman who is considered the real founder of the Katur rule in Chitral. He was followed by his son Shah Afzal II.

Mehtar Aman ul-Mulk (1857-1892)

Aman ul-Mulk, Shah Afzal's younger son, succeeded his brother in 1857. After a brief dispute with Kashmir, in which he laid siege to the garrison at Gilgit and briefly held the Punial valley. He accepted a treaty with the Maharaja in 1877. Aman ul-Mulk was such a strong ruler that no serious attempt to challenge his authority was made during his reign.[6] During the course of his rule Aman ul-Mulk met encountered many British officers some of whom have noted him in the following words.

His bearing was royal, his courtesy simple and perfect, he had naturally the courtly Spanish grace of a great heredity noble

— Algernon Durand

Chitral, in fact, had its parliament and democratic constitution. For just as the British House of Commons is an assembly, so in Chitral, the Mehtar, seated on a platform and hedged about with a certain dignity, dispensed justice or law in sight of some hundreds of his subjects, who heard the arguments, watched the process of debate, and by their attitude in the main decided the issue. Such 'durbars' were held on most days of the week in Chitral, very often twice in the day, in the morning and again at night. Justice compels me to add that the speeches in the Mahraka were less long and the general demeanour more decorous than in some western assemblies.

For forty years his was the chief personality on the frontier.[8] After a relatively long reign, he died peacefully in 1892.[9]

Wars of Succession

Without any law of succession, a long war of succession ensued between Aman ul-Mulk's sons after his death. Aman's younger son, Afzal ul-Mulk, proclaimed himself ruler during the absence of his elder brother. He then proceeded to eliminate several of his brothers, potential contenders to his throne. This initiated a war of succession, which lasted three years. Afzal ul-Mulk was killed by his uncle, Sher Afzal, the stormy petrel of Chitral and a long-time thorn in his father's side. He held Chitral for under a month, then fled into Afghan territory upon Nizam ul-Mulks return. Nizam, Afzal ul-Mulk's eldest brother and the rightful heir, then succeeded in December of the same year. At about that time, Chitral came under the British sphere of influence following the Durand Line Agreement, which delineated the border between Afghanistan and the British Indian Empire. Nizam ul-Mulk's possessions in Kafiristan and the Kunar Valley were recognised as Afghan territory and ceded to the Amir. Within a year, Nizam was himself murdered by yet another ambitious younger brother, Amir ul-Mulk. The approach of the Chitral Expedition, a strong military force composed of British and Kashmiri troops prompted Amir to eventually surrender, his patron, the Umra Khan fled to Jandul.[10]

The reign of Shuja ul-Mulk (1895–1936)

The British had decided to support the interests of Shuja ul-Mulk, the youngest legitimate son of Aman ul-Mulk, and the only one untainted by the recent spate of murder and intrigue. After installing the young Mehtar, British and dogra forces endured the famous defence against a seven-week siege by Sher Afzal and the Umra Khan of Jandul. Although Shuja ul-Mulk was now firmly established as ruler, the Dogras annexed Yasin, Kush, Ghizr and Ishkoman. Dogra suzerainty over Chitral ended in 1911, and Chitral became a Salute state in direct relations with the British. Mastuj, also removed from the Mehtar's jurisdiction in 1895, was restored to him within two years.

Shuja reigned for forty-one years, during which Chitral enjoyed an unprecedented period of internal peace. He journeyed outside of the Hindu Kush region, visiting various parts of India and meeting a number of fellow rulers, as well making the Hajj to Arabia and meeting Ibn SaudI. He was invited to the Delhi Durbar in January 1903.[11] Shuja ul-Mulk sent his sons abroad to acquire a modern education. The princes travelled to far-off places such as Aligarh and Dehradun accompanied by the sons of notables who were schooled at state expense.[2] He supported the British during the Third Anglo-Afghan War in 1919, during which four of his sons and the Chitral State Bodyguard served in several actions guarding the border against invasion.

Mehtars after Shuja ul-Mulk

Nasir ul-Mulk succeeded his father in 1936. He received a modern education, becoming a noted poet and scholar in his own right. He took a deep interest in military, political and diplomatic affairs, and spent much of his time on improving the administration. Dying without a surviving male heir in 1943, his successor was his immediate younger brother, Muzaffar ul-Mulk. Also a man with a military disposition, his reign witnessed the tumultuous events surrounding the Partition of 1947. His prompt action in sending in his own Bodyguards to Gilgit was instrumental in securing the territory for Pakistan.

The unexpected early death of Muzaffar ul-Mulk saw the succession pass to his relatively inexperienced eldest son, Saif-ur-Rahman, in 1948. Due to certain tensions he was exiled from Chitral by the Government of Pakistan for six years. They appointed a board of administration composed of officials from Chitral and the rest of Pakistan to govern the state in his absence. He died in a plane crash on the Lowari while returning to resume charge of Chitral in 1954.

Saif ul-Mulk Nasir (1950-2011)[12] succeeded his father at the age of four. He reigned under a Council of Regency for the next twelve years, during which Pakistani authority gradually increased over the state. Although installed as a constitutional ruler when he came of age in 1966, he did not enjoy his new status very long. Chitral was absorbed and fully integrated into the Republic of Pakistan by Yahya Khan in 1969. In order to reduce the Mehtar's influence, he, like so many other princes in neighbouring India, was invited to represent his country abroad. He served in various diplomatic posts in Pakistan's Foreign Office and prematurely retired from the service as Consul-General in Hong Kong in 1989. He died in 2011, and was succeeded (albeit largely symbolically) by his son Fateh ul-Mulk Ali Nasir.[13]

Accession, depletion and dissolution

At the time of the Partition of India, the then-Mehtar of Chitral, Muzaffar ul-Mulk chose to accede to Pakistan.[14] The state of Chitral executed an Instruments of Accession on 6 October 1947, which was contentedly accepted by the Government of Pakistan.[15] In 1954 a Supplementary Instrument of Accession was signed and the Chitral Interim Constitution Act was passed whereby the State of Chitral become a federated state of Pakistan.[16] The same year, a powerful advisory council was established on the insistence of the Federal Government of Pakistan. This body continued to govern Chitral until 1969.[17] The Frontier States of Dir, Chitral and Swat were finally merged through the promulgation of the Dir, Chitral and Swat Administration Regulation of 1969 under General Yahya Khan. The complete takeover of the administration by the Government of Pakistan meant that effectively the states had been extinguished.[18][19]

Abolition of titles

The titles, styles and privileges of the rulers of the former princely states of Pakistan, including Chitral, were abolished in April 1972,[20][21] through promulgation of the Rulers of Acceding States Abolition of Privy Purses and Privileges Order, 1972 (P. O. No. 15 of 1972). The new law took effect notwithstanding anything contained under any instrument of accession, agreement or any other law,[22] and has been entrenched further through the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution of Pakistan and Article 259 of the same.[23]

The withdrawal of titles is prospective in nature, restricting transference and new conferral from 1972 onwards but does not purport to disturb or affect previous operation of titles conferred.[19] The dormant titles are sometimes informally used even today in customary regard.[24]

Administration

Mehtar

The Mehtar was the center of all political, economic and social activity in the state. Intimacy with or loyalty to the ruling prince was a mark of prestige among the Mehtar's subjects.[2]

Civil Administration

The Mehtar was the source of all power in the land, the final authority on civil, military and judicial matters. To function effectively, he built an elaborate administrative machinery. From Chitral, the Mehtar maintained control over distant parts of the state by appointing trusted officials. From the Chitral fort, which housed the extended royal family, the Mehtar presided over an elaborate administrative hierarchy.[2]

State flag

The state flag of Chitral was triangular in shape and pale green in colour. The wider side of the pennant depicted a mountain, most likely the Terich Mir peak. In the later Katoor period, this flag served as a symbol of the Mehtar's presence and flew above the Chitral fort. It was hoisted every morning, accompanied by a salute from the State Bodyguard Force, and taken down each evening after another salutation.[2]

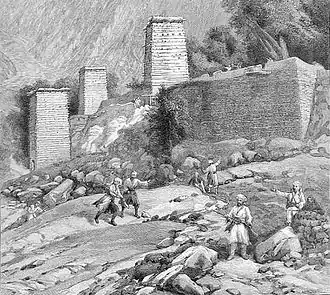

Royal Fort, the Shahi Mosque and the summer residence

The forts of Chitral have historically resembled medieval castles. They were both fortified residence and the seat of power in the area.[25] The Mehtars' fort in Chitral has a commanding position on the Chitral river. It remains the seat of the current ceremonial Mehtar. To the west of the fort is the Shahi Masjid, built by Shuja ul-Mulk in 1922. Its pinkish walls and white domes make it one of north Pakistan's most distinctive mosques.[26] The tomb of Mehtar Shuja ul-Mulk is located in a corner of the mosque. The summer residence of the ex-ruler of Chitral is on the hill top above the town at Birmoghlasht. This mountain top towers over the Chitral town and the summer residence is at a height of 2743 meters (9,000 feet).[27]

Scions of the royal family of Chitral

The scions of the Katur dynasty are still widely respected and honoured by the Katur tribe of Chitral today. The last ruling Mehtar Muhammad Saif-ul-Mulk Nasir was educated at Aitchison College.[28] He had received Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal (1953) and Pakistan Republic Medal (1956) .[29] He was married to the daughter of Nawab Muhammad Saeed Khan, the Nawab of Amb and has two sons and two daughters including:

1. Mehtar Fateh-ul-Mulk Ali Nasir, elder son of Mehtar Muhammad Saif-ul-Mulk Nasir, was appointed as Head of the Katur Royal House of Chitral on 20 October 2011, after the death of his father. He studied law at the universities of Buckingham and Miami.

2. Shahzada Hammad ul-Mulk Nasir, born 20 September 1990.

Politics

The family continues to be one of the strongest political forces in the district, although it has not consistently aligned itself with any particular party in the district.[30] Shahzada Mohiuddin, grandson of Shuja ul-Mulk, served as the Minister of State for Tourism in the 1990s.[31] He was twice elected as Chairman District Council Chitral, once as District Nazim, and four times as Member National Assembly of Pakistan (MNA).[32] Shahzada Mohiuddin also served as Chairman National Assembly Standing Committee on Kashmir Affairs and Northern Areas (KANA).[33] His son, Shahzada Iftikhar Uddin is the current MNA of Chitral.[34]

Notable members of the royal family

Mata ul-Mulk, one of the youngers son of Shuja ul-Mulk, served as Cammandar of the Indian National Army In Singapore.[35] He is best known for defeating the Sikh forces in Skardu commanding the Chitral Bodyguard, during the Siege of Skardu.[36][37]

Burhanuddin, son of Shuja ul-Mulk, served as Commander of the Indian National Army in Burma. He also served as a Senator after the World War II.[38]

Colonel Khushwaqt ul-Mulk, one of the younger sons of Shuja ul-Mulk, served as the Commandant of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) Rifles. He was educated at the Prince of Wales Royal Indian Military College (now the Rashtriya Indian Military College) at Dehradun, India. Following his father's death in 1936 he became the Governor of Upper Chitral.[39] He was a philanthropist and helped the Brooke Hospital for Animals, the British-based equine charity, to set up a centre in Pakistan. At the time of his death, he was the most senior surviving military officer of the Pakistan Army.[40] His youngest son Sikander ul-Mulk has captained the Chitral Polo Team at Shandur for over two decades.[41][42][43][44][45] His eldest son Siraj ul-Mulk has served in Pakistan Army and Pakistan International Airlines as a pilot.[46][47]

Masood ul-Mulk grandson of Shuja ul-Mulk, is a Pakistani expert on humanitarian aid.[48] He is the son of Khush Ahmed ul-Mulk, the last surviving son of Shuja ul-Mulk.[49][50] Khush Ahmed ul-Mulk served in the British Indian Army. As of 2014 he was the most senior surviving member of Chitral's royal family.

Taimur Khusrow ul-Mulk, grandson of Shuja ul-Mulk, and son of the daughter of the Nawab of Dir, served as a bureaucrat with the Federal Government of Pakistan[51] and served as Accountant General Khyber Pakhtunkhwa prior to his retirement in 2016.[52]

List of rulers

The rulers of the Kator dynasty with the date of their accession:

|

See also

References

- "Brief History of Ex Mehter Chitral HH Prince Saif ul Mulk Nasir".

- Pastakia 2004

- Osella, Coares (19 March 2010). Islam, Politics, Anthropology. ISBN 9781444324419.

- "History of Chitral- An outline".

- "Chitral: A Bloody History and a Glorious Geography".

- Gurdon, Lieut.-Colonel B.E.M. "Chitral Memories". The Himalayan Club.

- "Democratic to the Core". Archived from the original on 21 December 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- Durand, Algernon. "A Month in Chitral by Algernon Durand (London 1899)".

- "The Siege and Relief of Chitral".

- "Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 10, p. 302". Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- "Chitral". Project Gutenberg.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 25 September 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Rahman, Fazlur (1 January 2007). Persistence and transformation in the Eastern Hindu Kush: a study of resource management systems in Mehlp Valley, Chitral, North Pakistan. In Kommission bei Asgard-Verlag. p. 32. ISBN 9783537876683.

- Sultan-i-Rome (1 January 2008). Swat State (1915-1969) from Genesis to Merger: An Analysis of Political, Administrative, Socio-political, and Economic Development. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195471137.

- The North-west Frontier Province Year Book. Manager, Government Ptg. & Staty. Department. 1 January 1954. p. 229.

- "Familial glory: In Chitral and Swat, what's in a name? - The Express Tribune". 24 April 2013.

- Long, Roger D.; Singh, Gurharpal; Samad, Yunas; Talbot, Ian (8 October 2015). State and Nation-Building in Pakistan: Beyond Islam and Security. Routledge. p. 96. ISBN 9781317448204.

- "A Princely Affair". oup.com.pk. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016.

- Appalachia. Appalachian Mountain Club. 1 January 2008. p. 66.

- Assembly, Pakistan National (14 August 1972). Parliamentary Debates. Official Report. p. 160.

- "Former Acceding/Merged States of Pakistan". Ministry of States and Frontier Regions Government of Pakistan. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016.

- "Constitution (Fourth Amendment) Act, 1975". www.pakistani.org.

- "Chitral News, Views, Travel, Tourism, Adventure, Culture, Lifestyle". Chitral Times. 20 October 2011. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013.

- Woodburn, Bill. "Forts of the Chitral Campaign of 1895".

- Brown, Clammer, Cocks, Mock, Lindsay, Paul, Rodney, John (2008). Pakistan and the Karakoram Highway. p. 225. ISBN 9781741045420.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Chitral".

- "Brief History of Ex Mehter Chitral Prince Saif ul Mulk Nasir". Chitral Times. 25 October 2013. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- "Brief History of Ex Mehter Chitral Prince Saif ul Mulk Nasir". Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- Cutherell, Danny. "Governance and Militancy in Pakistan's Chitral district" (PDF). Center for Strategic and International Studies.

- "Future of five devolved PTDC motel employees uncertain". Chitral Today. 21 July 2013. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- "Familial glory: In Chitral and Swat, what's in a name?". The Express Tribune.

- "MNA elected NA Committee Chairman". Chitral News. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- "Iftikhar Uddin". Election Pakistan 2013. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- Chibber, Manohar Lal (1 January 1998). Pakistan's Criminal Folly in Kashmir: The Drama of Accession and Rescue of Ladakh. Manas Publications. ISBN 9788170490951.

- Singh, Bikram; Mishra, Sidharth (1 January 1997). Where Gallantry is Tradition: Saga of Rashtriya Indian Military College : Plantinum Jubilee Volume, 1997. Allied Publishers. ISBN 9788170236498.

- Journal of the United Service Institution of India. United Service Institution of India. 1 January 1988.

- "Remembering Burhanuddin". Chitral News. Archived from the original on 13 August 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- "Colonel Khushwaqt-ul-Mulk". The Telegraph. 17 March 2010.

- "Shahzada Col (R) Khushwaqt ul-Mulk laid to rest in Mastuj". Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- "Battle for the high ground: saving the polo festival at the world's highest pitch".

- "No quarter given in world's highest polo match".

- "Shandur Polo Match". The Guardian. 11 July 2009.

- Chitral, Declan Walsh on how the 'Palin effect' is drawing tourists to (6 July 2005). "Few rules, no referee and the wildest polo anywhere as Pakistan towns battle it out". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077.

- "26 beautiful photos you won't believe were taken in Pakistan". The Telegraph.

- Khan, Rina Saeed (3 August 2015). "Chitral floods: Why melting glaciers may not be the cause". Dawn.

- Pass, Declan Walsh Shandur (10 July 2009). "In the middle of war, a game of polo breaks out in Pakistan". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077.

- "Pakistani Relief Expert to Speak at Cambridge". University of Cambridge.

- Najib, Shireen (25 June 2013). My Life, My Stories. Dorrance Publishing. ISBN 9781480900004.

- Bowersox, Gary W. (1 January 2004). The Gem Hunter: True Adventures of an American in Afghanistan. GeoVision, Inc. ISBN 9780974732312.

- "Punjab governor's PS removed - The Express Tribune". 8 October 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- APP (1 August 2015). "Accountability offices in Fata". Retrieved 24 June 2016.

Further reading

- Pastakia, Firuza (2004). Chitral: A Study in Statecraft (1320–1969) (PDF). Peshawar, Pakistan: IUCN Pakistan. ISBN 9789698141691. OCLC 61520660. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- History of Chitral: An Outline

- Tarikh-e-Chitral

- Chitral States Judicial System

- Tribes of the Hindoo Koosh by John Biddulph