Chokecherry and Sierra Madre Wind Energy Project

The Chokecherry and Sierra Madre Wind Energy Project is large-scale wind farm located near Rawlins, Wyoming, currently under construction. If completed as scheduled in 2026, it is expected to become the largest wind farm in the United States and one of the largest in the world.[1][2]

| Chokecherry and Sierra Madre Wind Energy Project | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | United States |

| Location | Near Rawlins, Wyoming |

| Coordinates | 41°42′N 107°12′W |

| Status | Under construction |

| Construction began | January 2017 |

| Commission date | 2026 (expected) [1] |

| Owner(s) | Power Company of Wyoming |

| Power generation | |

| Nameplate capacity | 2,500 - 3,000 MW |

History and context

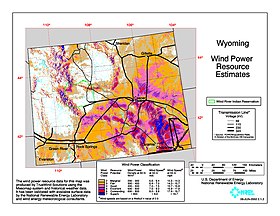

Power Company of Wyoming (PCW) began planning around 2005 for approximately 1,000 wind turbines on lands owned by The Overland Trail Ranch,[3] located south of Rawlins, Wyoming, in Carbon County, a former coal mining area.[4] In 2007, PCW installed 10 test turbines to test and verify the wind resources in the proposed area.[5] With this project, Wyoming is following the footsteps of Iowa, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas in taking advantage of its substantial wind resources. Major barriers to the development of wind power in Wyoming include an aging power grid, opposition due to aesthetics, concerns over the impact of wind turbines on airborne wildlife, and skepticism from the backbone of the state's economy the fossil fuel industry. However, falling oil and coal prices have incentivized the state to reconsider its position with regards to renewable energy. According to economist Robert Godby at the University of Wyoming, who studied the impact of wind power in his state, the addition of 6,000 MW of wind power could generate over $2 billion in tax revenue and $10 billion in investments in ten years. He added that while it may not be enough to replace coal, its positive impact is considerable.[2]

The Chokecherry and Sierra Madre Wind Energy Project is financially backed by Philip Anschutz, a billionaire from Denver who made his fortune largely in the fossil fuel industry. In general, support for it comes not from political ideology but rather economics. Thanks to efforts by private companies and state governments looking for better ways to harness renewable energy and to combat climate change, the wind power industry is now becoming more and more financially feasible and economically competitive, enough to satisfy fiscal conservatives.[2]

This is one of the priority infrastructure projects of the Trump administration in 2017.[6] In January that year, it obtained approval from the U.S. Bureau of Land Management for its first phase, the construction and installation of 500 wind turbines. The Fish and Wildlife Service also gave the green light. Both agencies said that not only is the environmental impact of this phase negligible, it would be a net positive for the eagles in the area. PCW claimed that the 1,500 MW of power generated from the first phase of the project could help reduce U.S. carbon emissions by millions of tons per year.[7]

Project

The project is proposed to generate 2,000 to 3,000 megawatts (MW) of electricity and construction may take 3–4 years with a project life estimate of 30 years.[8][9][10][11] Upon completion, there will be about 1,000 wind turbines,[7] occupying around 1,500 acres (6.1 km2).[12]

While winds in Texas and Iowa often blow at night, wind increases during the day in Wyoming, corresponding with consumption, as peak demand is late afternoon. The wind is Class 7,[13] and the wind capacity factor is around 46%.[14]

The first phase of 1,500 MW is expected to yield 6 TWh per year.[15] Erecting the turbines would be difficult in daytime winds, and PCW plans to set them up at night. The turbines are to be brought on site by a new rail spur, and then distributed by 500 miles (805 km) of new construction roads.[13]

The wind farm's original construction schedule had phase I built between 2016 and 2019 and phase II from 2022–2023.[16] As of 2019, the wind farm is now scheduled to be completed by 2026. There will be a transmission line to serve California.[17] It could help that state achieve its renewable energy targets by 2030.[7]

Economics

Impact Assistance to the local communities is expected to be $53 million, most of it to Carbon. Tax revenue could be $780 million.[18][19] During construction, 400 workers would be employed on average, but peaking at 900. After construction, 114 people would be permanently employed.[20]

The associated 3,000 MW HVDC TransWest Express Transmission Line (also owned by PCW) from the area to Las Vegas (730 miles; 1,175 km)[21] is expected by NREL analysts save $500 million to around $1 billion per year for Californian consumers, compared to Californian alternatives.[14][22][13] The TWE received approvals in December 2016/January 2017.[23][24]

Wyoming is one of the few U.S. states to tax wind power. This was done in order to protect the coal, oil, and natural gas industry, the backbone of the state economy.[2] As of 2017, Wyoming remained heavily dependent on the coal industry, from which derived 40% of U.S. coal.[7] With public support, the state government eliminated its sales-and-use tax exemption for utility-scale renewable-energy equipment in 2009 and imposed a $1 per megawatt-hour tax on wind power in 2010.[2] A tax increase may impact the economics of the project.[25][26] In all, taxes have increased the cost of the project by about $440 million. Efforts by some state legislators to raise the tax to $3 or even $5 per megawatt-hour have all been defeated, as of 2017. Nevertheless, any further tax hikes would likely kill the project altogether.[2]

Regulatory process

PCW applied to the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) in 2008 to build the $5 billion project, which was initially approved in 2012,[27] and a second approval came in March 2016.[15] There are many different approvals to apply for, and the BLM struggled to build a regulatory system capable of handling the many new large solar and wind projects on federal lands.[28] In April 2016, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service released a draft environmental impact statement on the project for 60 days of public comment.[29][30] BLM and FWS provided partial approvals in January 2017.[31][32]

Environment

The area is sensitive for sage-grouse. Up to 50 biologists have tagged 370 grouse since 2010, researching their behavior around the area. A team researches golden eagles, as an "eagle take" permit is necessary. The research is to be continued during construction and operation of the wind farm so as to be compared with the condition prior to construction. The $3 million research project is paid by PCW.[13] The Bureau of Land Management estimated 40-64 eagles per year for 1,000 turbines, whereas the Fish and Wildlife Service estimates 10-16 for 500 turbines.[33]

See also

References

- camille.erickson@trib.com, Camille Erickson 307-266-0592. "Work on Wyoming's largest wind farm project continues even as schedule changes". Casper Star-Tribune Online. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- Paulson, Amanda (December 29, 2017). "Why coal-rich Wyoming is investing big in wind power". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- The Overland Trail Ranch

- Urbanek, Mae (1988). Wyoming Place Names. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing Company. ISBN 0-87842-204-8.

- Adam Voge (May 28, 2013). "Intensive work begins on Wyoming wind power mega-project". Casper Star-Tribune Online.

- Trump makes $137bn list of “emergency” infrastructure schemes, all needing private finance. Global Construction Review. January 30, 2018. Accessed February 10, 2019.

- Walton, Robert (January 19, 2017). "Feds approve 1st phase of largest US wind project in Wyoming". Utility Dive. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- Bureau of Land Management (July 22, 2011). "Chokecherry/Sierra Madre Wind Energy Comment Period Opens". Archived from the original on August 16, 2014. Retrieved May 31, 2015.

- Tina Casey (July 7, 2015). "Billionaire on way to building largest wind farm in North America". CleanTechnica.

- Ros Davidson (November 1, 2014). "Wyoming wind on the long trail west". Windpower Monthly.

- Benjamin Storrow (July 25, 2015). "Will California's renewable energy mandate benefit the Chokecherry Sierra Madre wind farm?". Casper Star-Tribune Online.

- Beers, Cody (December 19, 2019). "Wyoming's largest wind farm extends construction schedule". Cowboy State Daily. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019.

- Gabriel Kahn (June 29, 2015). "How a Conservative Billionaire Is Moving Heaven and Earth to Become the Biggest Alternative Energy Giant in the Country". Pacific Standard. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

[Most wind power in these places is generated at night, when the winds blow the hardest; that's the time, of course, when people need it the least. But along the ridges of the Overland Trail Ranch are some of the only Class 7 winds in the nation. What's more, the wind on the ranch starts up in the morning and gains force throughout the day, just when people are firing up their air conditioners and dishwashers.] [..take wind-generated electricity straight from Wyoming across Colorado, Utah, and Nevada and dump it into a substation on the California-Nevada border — a location that technically was part of the California grid]

- D. Corbus, D. Hurlbut, P. Schwabe, E. Ibanez, M. Milligan, G. Brinkman, A. Paduru, V. Diakov, and M. Hand. "California-Wyoming Grid Integration Study", page vi-xii. National Renewable Energy Laboratory, March 2014. NREL/TP-6A20-61192

- "BLM issues Environmental Assessment for Phase I Wind Turbine Development for the CCSM Project".

- "Analysis: Mega-projects, the big hope of US wind". Windpower Monthly.

- "Schedule changes for Wyoming's largest wind farm project". Associated Press. July 9, 2019. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- "Counties negotiate Chokecherry wind energy project impact funds". Laramie Boomerang. June 12, 2014.

- BLM report moves Chokecherry closer to reality Rawlins Times, 10 March 2016

- The tale of the magic wind farm fairy Rawlins Times, 12 March 2016

- "TransWest Express Transmission Project: Delivering Wyoming Wind Energy". TransWest Express.

- Thomas J. Dougherty (March 30, 2014). "Favorable Winds Continue to Blow for TransWest Express Transmission Project". The National Law Review. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- "Global Transmission Report : TransWest Express Project, US". January 6, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- "Environmental analysis concludes for TransWest". Rawlins Times. January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

This closes out that overall environmental process

- Marc Del Franco. "In Wyoming, The Tax Man Cometh For More". Archived from the original on June 11, 2016. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- "Wind tax proposal complicates huge Wyo plan". Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- "U.S. approves huge wind farm in Wyoming". MNN - Mother Nature Network.

- Elizabeth Shogren (December 13, 2015). "Bureaucratic gauntlet stalls renewable energy development on BLM land". High Country News.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: Mountain-Prairie Region. "Public Comment Sought on Draft Environmental Impact Statement Evaluating Impacts from Proposed Chokecherry and Sierra Madre Phase I Wind Energy Project". United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- "Wind Energy: Chokecherry Sierra Madre Phase I Project". United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- "Feds approve 1st phase of largest US wind project in Wyoming". Utility Dive. January 19, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- "Decision for Eagle Take Permits for the Chokecherry and Sierra Madre Phase I Wind Energy Project" (PDF). United States Fish and Wildlife Service. January 19, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

The Service identified the proposed action (Alternative 1) as the preferred alternative.

- "Federal eagle take permit weighed for huge Wyoming wind farm". The Washington Times. Retrieved April 21, 2016.