Circumcision and HIV

The relationship between circumcision and HIV has been researched since the late 1980s. Male circumcision reduces the risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission from HIV+ women to men.[1][2]

In 2011, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) stated that male circumcision is an efficacious intervention for HIV prevention if carried out by medical professionals under safe conditions.[3][4][5] The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) states that circumcision reduces the risk that a man will acquire HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) from an infected female partner.

Efficacy

Heterosexual men

As of 2020, circumcision is well-established as being effective at reducing the risk of HIV infection in heterosexual men.[1]

The number needed to treat, to prevent one HIV infection during ten years, is between five and fifteen men. The UNAIDS/WHO/SACEMA Expert Group on Modelling the Impact and Cost of Male Circumcision for HIV Prevention found "large benefits" of circumcision in settings with high HIV prevalence and low circumcision prevalence. The Group estimated "one HIV infection being averted for every five to fifteen male circumcisions performed, and costs to avert one HIV infection ranging from US$150 to US$900 using a 10-y time horizon".[6] The World Health Organisation states that circumcision is "highly cost-effective" in comparison to other HIV interventions when data from the South African trial are used, but less cost-effective when data from the Ugandan trial are used.[3]

Studies have found that newly-circumcised HIV infected men who have not had antiretroviral therapy can shed the HIV virus from the circumcision wound, thus increasing the immediate risk of HIV transmission to female partners. This risk of post-operative transmission presents a challenge, although in the long-term it is likely the circumcision of HIV-infected men helps lessen heterosexual HIV transmission overall. Such viral shedding can be mitigated by the use of antiretroviral drugs.[7]

Men who have sex with men

A 2008 meta-analysis of gay and bisexual men (52% circumcised) found that the rate of HIV infection was not lower among men who were circumcised.[8] For men who engaged primarily in insertive anal sex, no effect was observed. Observational studies included in the meta-analysis that were conducted prior to the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy in 1996 demonstrated a protective effect for circumcised men who have sex with men (MSM) against HIV infection.[8]

Reviews in 2011[9] and 2018 found some evidence that circumcision was protective in MSM.[10]

A 2019 meta-analysis of MSM found circumcision was associated with a 42% reduction in the odds of HIV in low and middle income countries, but not in high income countries.[8] The CDC stated in 2013: "There are as yet no convincing data to help determine whether male circumcision will have any effect on HIV risk for men who engage in anal sex with either a female or male partner, as either the insertive or receptive partner."[11]

Recommendations

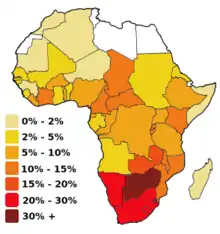

In 2007, the WHO reviewed the totality of evidence concerning male circumcision and HIV, and issued joint recommendations with UNAIDS.[5] The recommendations included that male circumcision is an efficacious intervention for HIV prevention and that the promotion of male circumcision is an additional strategy for the prevention of heterosexually acquired HIV infection in men.[4] Kim Dickson, coordinator of the working group that authored the report, commented in part that circumcision "would have greatest impact" in countries with relatively high heterosexual HIV transmission rates (greater than 15%) and low circumcision rates (less than 20%). She further commented that circumcision is not full protection and that other methods of HIV prevention are still important in circumcised males.[12]

Although these results demonstrate that male circumcision reduces the risk of men becoming infected with HIV, the UN agencies emphasize that it does not provide complete protection against HIV infection. Circumcised men can still become infected with the virus and, if HIV-positive, can infect their sexual partners. Male circumcision should never replace other known effective prevention methods and should always be considered as part of a comprehensive prevention package, which includes correct and consistent use of male or female condoms, reduction in the number of sexual partners, delaying the onset of sexual relations, and HIV testing and counselling.

— World Health Organization, Joint WHO/UNAIDS Statement.[13]

Because the evidence that circumcision prevents HIV mainly comes from studies conducted in Africa, the Royal Dutch Medical Association (KNMG) has questioned the applicability of those studies to developed countries. Circumcision has not been included in their HIV prevention recommendations. The KNMG policy statement says that the relationship between HIV transmission and circumcision is unclear, and that behavioral factors seem to have more of an effect on HIV prevention than circumcision. The KNMG also recommends that the choice of circumcision should be put off until an age when a possible HIV risk reduction would be relevant, so that boys can decide for themselves whether to undergo the procedure or choose other prevention alternatives. This KNMG circumcision policy statement was endorsed by several Dutch medical associations.[14]

In the United States, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) led a 2012 task force which included the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). The task force policy statement, found that circumcision may be helpful for the prevention of HIV in the United States. The AAP task force policy was endorsed by the ACOG.[15] The CDC expressed uncertainty if circumcision would help in the United States, stating the transmission patterns in the U.S. vary from those studied in the primary studies examined, namely the U.S. has a higher prevalence of MSM transmission. In line with the AAP task force, the CDC 2018 position on circumcision and HIV recommended that circumcision should continue to be offered to parents who are informed of the benefits and risks, including a potential reduction in risk of HIV transmission.[16] The CDC says that circumcision can be done in adulthood, when the man can make a decision for himself. Circumcision conducted after sexual debut can result in missed opportunities for HIV prevention.[16]

Process

The WHO recommends voluntary medical male circumcision, as opposed to circumcision by traditional healers or untrained individuals.

Newly circumcised men must refrain from sexual activity until the wounds are fully healed. Some circumcised men might have a false sense of security that could lead to increased risky sexual behavior.[17]

Mechanism of action

While the biological mechanism of action is not known, a 2020 meta-analysis stated "the consistent protective effect suggests that the reasons for the heterogeneity lie in concomitant individual social and medical factors, such as presence of STIs, rather than a different biological impact of circumcision."[1]

Experimental evidence supports the theory that Langerhans cells (part of the human immune system) in foreskin may be a source of entry for the HIV virus.[18] Excising the foreskin removes what is thought to be a main entry point for the HIV virus.[19]

History

Valiere Alcena, in a 1986 letter to the New York State Journal of Medicine, noted that low rates of circumcision in parts of Africa had been linked to the high rate of HIV infection.[20][21] Aaron J. Fink several months later also proposed that circumcision could have a preventive role when the New England Journal of Medicine published his letter, "A possible explanation for heterosexual male infection with AIDS," in October, 1986.[22] By 2000, over 40 epidemiological studies had been conducted to investigate the relationship between circumcision and HIV infection.[23] A meta-analysis conducted by researchers at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine examined 27 studies of circumcision and HIV in sub-Saharan Africa and concluded that these showed circumcision to be "associated with a significantly reduced risk of HIV infection" that could form part of a useful public health strategy.[24]

A 2005 review of 37 observational studies expressed reservations about the conclusion because of possible confounding factors, since all studies to date had been observational as opposed to randomized controlled trials. The authors stated that three randomized controlled trials then underway in Africa would provide "essential evidence" about the effects of circumcision on preventing HIV.[25]

In 2009, a Cochrane review which included the results of the three 2000s trials found "strong" evidence that the acquisition of HIV by a man during sex with a woman was decreased by 38% and 66% over 24 months if the man was circumcised. The review also found a low incidence of adverse effects from circumcision in the trials reviewed.[26] In 2020, a review including post-study follow up from the three randomized controlled trials, as well as newer observational studies, found a 59% reduction in HIV incidence across the three randomized controlled trials, as well as continued protection for up to 6 years after the studies began.[27]

Society and culture

The prevalence of circumcision varies across Africa.[28][29] Studies were conducted to assess the acceptability of promoting circumcision; in 2007, country consultations and planning to scale up male circumcision programmes took place in Botswana, Eswatini, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Rwanda, South Africa, Uganda, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe.[30]

Programs

In 2011, UNAIDS prioritized 14 high HIV prevalence countries in eastern and southern Africa, with a goal of circumcising 80% of men (20.8 million) by the end of 2016.[31] In parallel, WHO developed a Framework for evaluating new, simpler circumcision techniques, which gave impetus to the development of two new devices (Prepex and Shang Ring) that are currently being scaled-up in the 14 high HIV prevalence countries.[32] Overall, 14.5 million males were circumcised as of the end of 2016.[33]

UNAIDS' Fast-Track Plan for ending the AIDS Epidemic by 2030 calls for an additional 25 million circumcisions in these high-priority countries by 2020, which will require to 5 million procedures per year, nearly double the current rate.[34] To reach this goal, UNAIDS is counting on advances in circumcision techniques.[32]

See also

References

- Farley TM, Samuelson J, Grabowski MK, Ameyan W, Gray RH, Baggaley R (June 2020). "Impact of male circumcision on risk of HIV infection in men in a changing epidemic context - systematic review and meta-analysis". J Int AIDS Soc (Review). 23 (6): e25490. doi:10.1002/jia2.25490. PMC 7303540. PMID 32558344.

- Jameson JL, Kasper DL, Longo DL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Loscalzo J (2018). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (20th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education. p. 1400. ISBN 978-1-259-64403-0. OCLC 1029074059.

- "Male circumcision: Global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety and acceptability" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2007. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- New Data on Male Circumcision and HIV Prevention: Policy and Programme Implications (PDF) (Report). World Health Organization. March 28, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- "WHO and UNAIDS announce recommendations from expert consultation on male circumcision for HIV prevention". World Health Organisation. March 2007.

- Hankins C, Hargrove J, Williams B, Abu Raddad L, Auvert B, Bollinger L, et al. (UNAIDS/WHO/SACEMA Expert Group on Modelling the Impact and Cost of Male Circumcision for HIV Prevention) (September 2009). "Male circumcision for HIV prevention in high HIV prevalence settings: what can mathematical modelling contribute to informed decision making?". PLOS Medicine (Review). 6 (9): e1000109. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000109. PMC 2731851. PMID 19901974.

- Tobian AA, Adamu T, Reed JB, Kiggundu V, Yazdi Y, Njeuhmeli E (December 2015). "Voluntary medical male circumcision in resource-constrained settings". Nat Rev Urol (Review). 12 (12): 661–70. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2015.253. PMID 26526758.

- Yuan T, Fitzpatrick T, Ko NY, Cai Y, Chen Y, Zhao J, et al. (April 2019). "Circumcision to prevent HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of global data". The Lancet. Global Health. 7 (4): e436–e447. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30567-9. PMC 7779827. PMID 30879508.

- Wiysonge CS, Kongnyuy EJ, Shey M, Muula AS, Navti OB, Akl EA, Lo YR (June 2011). "Male circumcision for prevention of homosexual acquisition of HIV in men". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD007496. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007496.pub2. PMID 21678366.

- Sharma SC, Raison N, Khan S, Shabbir M, Dasgupta P, Ahmed K (April 2018). "Male circumcision for the prevention of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) acquisition: a meta-analysis". BJU International. 121 (4): 515–526. doi:10.1111/bju.14102. PMID 29232046.

- "Male Circumcision". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-12-21.

- "WHO hails circumcision as vital in HIV fight". New Scientist. March 28, 2007. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- "WHO and UNAIDS Secretariat welcome corroborating findings of trials assessing impact of male circumcision on HIV risk" (Press release). World Health Organization. February 23, 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- "Non-therapeutic circumcision of male minors - KNMG Viewpoint".

- American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision (2012). "Technical Report". Pediatrics. 130 (3): e756–e785. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1990. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 22926175. Archived from the original on 2012-09-20.

- "Information for providers counseling male patients and parents regarding male circumcision and the prevention of HIV infection, STIs, and other health outcomes". CDC stacks. Centers for Disease Control. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Kalichman S, Eaton L, Pinkerton S (March 2007). "Circumcision for HIV prevention: failure to fully account for behavioral risk compensation". PLOS Medicine. 4 (3): e138, author reply e146. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040138. PMC 1831748. PMID 17388676.

- Weiss HA, Dickson KE, Agot K, Hankins CA (October 2010). "Male circumcision for HIV prevention: current research and programmatic issues". AIDS (Randomized controlled trial). 24 Suppl 4 (Suppl 4): S61-9. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000390708.66136.f4. PMC 4233247. PMID 21042054.

- Szabo R, Short RV (June 2000). "How does male circumcision protect against HIV infection?". BMJ (Review). 320 (7249): 1592–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7249.1592. PMC 1127372. PMID 10845974.

- Alcena V (19 October 2006). "AIDS in Third World countries". PLOS Medicine (Comment). 86 (8): 446. PMID 3463895.

- Alcena V (August 1986). "AIDS in Third World countries". New York State Journal of Medicine (Letter). 86 (8): 446. PMID 3463895.

- Fink AJ (October 1986). "A possible explanation for heterosexual male infection with AIDS". The New England Journal of Medicine (Letter). 315 (18): 1167. doi:10.1056/nejm198610303151818. PMID 3762636.

- Szabo R, Short RV (June 2000). "How does male circumcision protect against HIV infection?". BMJ (Review). 320 (7249): 1592–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7249.1592. PMC 1127372. PMID 10845974.

- Weiss HA, Quigley MA, Hayes RJ (October 2000). "Male circumcision and risk of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis". AIDS (Meta-analysis). 14 (15): 2361–70. doi:10.1097/00002030-200010200-00018. PMID 11089625. S2CID 21857086. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-01-10.

- Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks J, Volmink J, Egger M, Low N, et al. (March 2005). "HIV and male circumcision--a systematic review with assessment of the quality of studies". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases (Review). 5 (3): 165–73. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(05)01309-5. PMID 15766651.

- Siegfried, Nandi; Muller, Martie; Deeks, Jonathan J; Volmink, Jimmy (15 April 2009). "Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD003362. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003362.pub2. PMID 19370585.

- Farley, Timothy MM; Samuelson, Julia; Grabowski, M Kate; Ameyan, Wole; Gray, Ronald H; Baggaley, Rachel (June 2020). "Impact of male circumcision on risk of HIV infection in men in a changing epidemic context – systematic review and meta‐analysis". Journal of the International AIDS Society. 23 (6): e25490. doi:10.1002/jia2.25490. PMC 7303540. PMID 32558344.

- Marck J (1997). "Aspects of male circumcision in sub-equatorial African culture history" (PDF). Health Transition Review (Review). 7 Suppl (Suppl): 337–60. PMID 10173099. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-06. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- "Male circumcision: global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety and acceptability" (PDF). Who/Unaids. 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- "Towards Universal access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector" (PDF). Who/Unaids/Unicef: 75. 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- Joint strategic action framework to accelerate the scale-up of voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention in Eastern and Southern Africa, 2012-2016. WHO. 2014.

- Framework for Clinical Evaluation of Devices for Adult Male Circumcision (PDF) (Report). WHO. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-11-14. Retrieved 2017-08-20.

- Voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention in 14 priority countries in eastern and southern Africa, Progress brief (PDF) (Report). WHO. 2017.

- "Voluntary medical male circumcision: a core campaign to reach the Fast-Track Targets". UNAIDS. 2016.

External links

- "Male circumcision for HIV prevention". World Health Organization. Retrieved January 11, 2014.