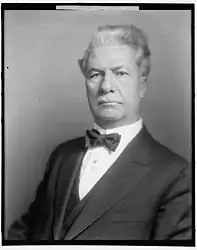

Coleman Livingston Blease

Coleman Livingston Blease (October 8, 1868 – January 19, 1942) was a South Carolina politician of the Democratic Party who served as Governor of South Carolina from 1911 to 1915, and as a United States Senator from 1925 to 1931. Blease was the political heir of Benjamin Tillman. He led a political revolution in South Carolina by building a political base of white textile mill workers from the state's upountry region. He was notorious for playing on the prejudices of poor whites to gain their votes and was an unrepentant white supremacist. Ultimately, despite his political strength, Blease failed to pass any significant legislation while governor.

Coleman Blease | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| United States Senator from South Carolina | |

| In office March 4, 1925 – March 3, 1931 | |

| Preceded by | Nathaniel B. Dial |

| Succeeded by | James F. Byrnes |

| 90th Governor of South Carolina | |

| In office January 17, 1911 – January 14, 1915 | |

| Lieutenant | Charles Aurelius Smith |

| Preceded by | Martin Frederick Ansel |

| Succeeded by | Charles Aurelius Smith |

| President Pro Tempore of the South Carolina Senate | |

| In office January 8, 1907 – January 12, 1909 | |

| Governor | Duncan Clinch Heyward Martin Frederick Ansel |

| Preceded by | Richard Irvine Manning III |

| Succeeded by | William Lawrence Mauldin |

| Member of the South Carolina Senate from Newberry County | |

| In office January 8, 1907 – January 12, 1909 | |

| Preceded by | George Sewell Mower |

| Succeeded by | Alan Johnstone |

| Member of the South Carolina House of Representatives from Newberry County | |

| In office January 10, 1899 – January 8, 1901 | |

| In office November 25, 1890 – November 27, 1894 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 8, 1868 Newberry, South Carolina |

| Died | January 19, 1942 (aged 73) Columbia, South Carolina |

| Resting place | Rosemont Cemetery, Newberry, South Carolina |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Lillie B. Summers Carolina Floyd |

| Parents | Henry Horatio Blease Mary Ann Livingston Blease |

| Alma mater | Georgetown University |

| Occupation | Attorney |

Blease was notorious for his vituperative demeanor. He did not campaign on political promises but on the prejudices of white citizens. Blease advocated lynching and was against education for blacks. As U.S. senator, he advocated penalties for interracial couples attempting to get married, criticized US First Lady Lou Hoover for inviting a black guest to tea at the White House, and was the architect of Section 1325.

Early life and political career

Blease was born to Henry Horatio Blease (1832–1892) and Mary Ann Livingston Blease (1830–1874) near the town of Newberry, South Carolina, on October 8, 1868, the year that South Carolina's new Reconstruction constitution was adopted, and black Americans began participating in political life. He grew up in his father's hotel which led him to be uncommonly social.[1] He was educated at Newberry College, the University of South Carolina, and Georgetown University, where he graduated from the law department in 1889.[2] At the University of South Carolina, Blease was expelled for plagiarism and always carried a grudge against the university.[3]

After his schooling was complete, Blease returned to Newberry to practice law and to enter politics. He began his political career in the South Carolina House of Representatives in 1890 as a Democrat and protégé of Benjamin Tillman.[4] In 1895, the state legislature ratified a new constitution that essentially disfranchised blacks, thus crippling the state's Republican Party, which they supported.[5] The state then had a one-party system, run by the Democrats.

Blease's rise to power, as he moved from the South Carolina House of Representatives to the South Carolina Senate in 1900, was built on the support of both the sharecroppers and white mill workers, then an increasingly-important segment of the electorate in South Carolina.[6] But it was not a straightforward rise, Blease lost his seat in the legislature in 1894 and his attempt to re-gain it in 1896.[7] And while he ultimately obtained a state senate seat in 1900, he subsequently lost races to become the Democratic nominee for governor in 1904 and 1906.[8]

In 1910, Blease was elected mayor of Newberry and held that position until November of that year, when he was elected governor of South Carolina.

Bleasism

Critics and allies of Blease alike used the term Bleasism to "designate the political uprising of first-generation South Carolina millworkers" led by Blease in 1910.[9] The political uprising was different from the one led by Ben Tillman a generation earlier. Whereas Tillman sought agricultural reform and drew his political support from South Carolina's white farmers and planters, Blease was anti-reform and drew his support from white textile mill workers.[10] The movement Blease led was largely characterized by white supremacy and not social policy.[11] But it shared the same enemies as Tillmanism: the newspapers, the railroads, corporations, Charleston aristocrats, and urban businessmen.[12]

Bleasism was made possible by the sociopolitical change South Carolina underwent at the turn of the twentieth century. For instance, in 1880, the state had close to a dozen textile mills, but in 1900 the number had grown to 115.[13] The work force of the mills also changed, becoming increasingly more male each year.[14] Because South Carolina was one of the few Southern states at the time that did not disenfranchise poor white men, Blease actively courted the workers of these mills and built a devoted political base from the men, who hung his photo in their homes and named their children after him.[15]

His appeal to the millworkers and sharecroppers was based on his personality and his view that made the "inarticulate masses feel that Coley was making them an important political force in the state."[16] In fact, little to no policy was tied to Blease but his invectives and shared tongue with the mill workers won him their favor.[17] Because of this, Blease was the only politician in South Carolina who had any independence from Tillman while Tillman was alive.[18]

Governor

Blease was elected governor in 1910 because he "knew how to play on race, religious, and class prejudices to obtain votes."[16] His legislative program was erratic and without consistency. He favored more aid to white schools but opposed compulsory attendance. He abolished the textile mill at the state penitentiary for health reasons but opposed inspections of private factories to ensure safe and healthful working conditions.[19]

Blease acquired such a bad reputation that he was said to represent the worst aspects of Jim Crow and Benjamin Tillman, who branded Blease's style as "Jim Tillmanism" (Jim Tillman was Benjamin Tillman's nephew, who, as lieutenant governor, had killed a newspaper editor and been acquitted in the case).[20] Blease favored complete white supremacy in all matters. He encouraged the practice of lynching, strongly opposed the education of blacks, and derided an opponent for being a trustee of a black school.[21] He fired administrators without the authority to do so, ignored patronage requests from state legislators, and sparred with the state Supreme Court.[22]

Blease failed to enforce laws and was a scofflaw.[23] On two occasions, he pardoned his black chauffeur when he was cited for speeding.[24] Enjoying the power to pardon, Blease said that he wanted to pardon at least 1000 men before he exited office because he wanted "to give the poor devils a chance."[25] He is estimated to have pardoned between 1,500 and 1,700 prisoners, some of whom were guilty of murder and other serious crimes.[26] His political enemies suggested that Blease received payments to pardon criminals. Among those he pardoned was former US Representative George W. Murray in 1912. The black Republican had lost an appeal for his conviction of forgery in 1905 by an all-white jury and was sentenced to hard labor. Refusing to serve for a conviction that he claimed resulted from racial discrimination, Murray had left the state permanently for Chicago.

Opposition to soft drinks

Blease disliked the newly-developed carbonated soft drinks. In his gubernatorial inaugural address in 1911, he said:

I also, in this connection, beg leave to call your attention to the evil of the habitual drinking of Coca-Cola, Pepsi-Cola, and such like mixtures, as I fully believe they are injurious. It would be better for our people if they had nice, respectable places where they could go and buy a good, pure glass of cold beer, than to drink such concoctions.[27]

Re-election in 1912

In 1912, Blease faced Ira B. Jones in the Democratic gubernatorial primary and narrowly won the contest, and subsequently another term as governor. Jones, a Tillmanite and Chief Justice on the state Supreme Court, was no match for Blease on the stump.[28] Jones claimed that Bleasism "led to anarachy" and campaigned on "law and order."[29] He had Charleston Mayor John P. Grace campaign against Blease in the upcountry.[30] Further, he argued that Blease rewarded his friends with positions in government.[31] But Blease ultimately prevailed in the contest.

Blease had made an agreement with Ben Tillman, who was running for re-election to the Senate, that the two would endorse each other. However, Tillman betrayed this promise several days before the election by releasing a letter denigrating Bleasism.[32]

After governorship, before becoming a Senator

Failed campaigns for the Senate

In 1914, before Blease's tenure as governor was over, Blease was so confident that he would be elected to the U.S. Senate if he ran that he visited the Senate chambers in Washington to choose his desk.[33] However, after numerous blunders including his speech at the 1912 National Governors' Conference in Richmond, Virginia, Blease's popularity had waned and the incumbent, Senator Ellison D. Smith was able to secure re-election by 15,000 votes.[34]

In a show of spite for progressive governor-elect Richard Irvine Manning III, Blease resigned five days before the end of his second term on January 14, 1915 so that he did not have to attend Manning's inauguration.[35] Lieutenant Governor Charles Aurelius Smith succeeded to the governorship and performed ceremonial functions during his five days in office.

After leaving office, Blease moved his criminal law practice from Newberry to Columbia and continued railing against his political enemies.[36] He occupied his time giving speeches in rural towns and discussing his use of the governor's parole power in national forums.[37] Further, he spoke out against Governor Manning's policies regarding prohibition (Blease popularly said he would not enforce the dispensary laws in the wet cities, Charleston and Columbia) and Manning's newly-created administrative agencies which he called useless.[38]

In 1917, Blease denounced America's entry into World War I.[39] However, he recanted this position the following year.[40] Nonetheless, his statements came back to haunt him when he ran for the 1918 Democratic nomination for the Senate after Tillman passed away. President Wilson declared that Blease was no friend of the administration, and former allies of Blease failed to endorse him, both occurrences led to Blease losing the race.[41]

Post-World War I

Following his loss in 1918, Blease was inactive politically for the next three years.[42] But as the political climate turned more reactionary after 1919, when the state and nation suffered with postwar economic adjustments, Blease's popularity rebounded. Blease did not run for any public office in 1920.[43] However, Blease threw his hat in the ring once again in 1922 when he ran for governor.[44] Blease failed to capture a majority of the votes and lost to Thomas Gordon McLeod in the run-off by over 15,000 votes.[45]

In virtually all of his campaigns, Blease used a catchy, nonsensical, nonspecific campaign jingle that became well known to virtually every voter in South Carolina in the era. For instance, he used, "Roll up your sleeves, say what you please... the man for the job is Coley Blease!"

Single term in the U.S. Senate and death

Election

In 1924, Blease defeated James F. Byrnes in the Democratic primary and was elected to the US Senate. His campaign foreshadowed his style as senator. Blease's defeat of Byrnes was widely credited to a rumor campaign that Byrnes, who was raised as a Roman Catholic in Charleston, had not really left that faith.[46] Such an assertion in an overwhelmingly-Protestant state, while the Ku Klux Klan was at the height of its power, ruined Byrnes's political hopes that year. Nonetheless, Blease was considerably more moderate in the election than in his previous political campaigns.[47]

Views and policies

In 1926, Blease proposed an anti-miscegenation amendment to the US Constitution to require Congress to set a punishment for interracial couples attempting to get married and for people officiating an interracial marriage, but Congress never submitted it to the states.

In 1929, in protest of First Lady Lou Hoover's invitation of Jessie DePriest, the African-American wife of Illinois Representative Oscar De Priest, to tea at the White House, Blease proposed a resolution, "[t]o request the Chief Executive to respect the White House," demanding for the Hoovers to "remember that the house in which they are temporarily residing is the 'White House'."[48] In support of the resolution, Blease read the 1901 poem "Niggers in the White House" on the floor of the Senate. After immediate protests from Northern Republican Senators Walter Edge and Hiram Bingham, the poem was excluded from the Congressional Record.[48][49] Bingham described the poem as "indecent, obscene doggerel" which gave "offense to hundreds of thousands of our fellow citizens and... to the Declaration of Independence and our Constitution."[49] Blease withdrew the resolution but said that he did so "because it gave offense to his friend, Senator Bingham, and not because it might give any offense to the Negro race."[49]

That year, Blease made a significant contribution to American immigration law. He brokered a compromise between dueling factions and shepherded a bill through congress which criminalized unlawful entry into the United States, this paved the way for Section 1325.[50]

Byrnes defeated Blease in his 1930 run for re-election to the Senate.[51] Blease died in Columbia, South Carolina on the night of January 19, 1942, a day after he underwent surgery.[52]

References

- Simkins 1944 p. 486.

- "Biographical Directory of the U.S. Congress - Cole Blease". bioguideretro.congress.gov. Retrieved 2020-12-14.

- Lander, Ernest: A History of South Carolina 1865-1960, p. 141. University of South Carolina Press, 1970.

- Simon, Bryant. The Appeal of Cole Blease of South Carolina: Race, Class, and Sex in the New South,” The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 62, No. 1 (Feb., 1996), pp. 57 – 59.

- Simkins 1967 p. 224.

- Lander, Ernest: A History of South Carolina 1865-1960, p. 49. University of South Carolina Press, 1970.

- Simkins 1944 p. 487.

- Id.

- Simon, Bryant (Feb 1996). "The Appeal of Cole Blease of South Carolina: Race, Class, and Sex in the New South". The Journal of Southern History. 62 (1): 60. doi:10.2307/2211206. JSTOR 2211206.

- Id.

- Id. at 66.

- Stone, C. (1963). BLEASEISM AND THE 1912 ELECTION IN SOUTH CAROLINA. The North Carolina Historical Review, 40(1), 54-74. Retrieved December 17, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23517346

- Simon 1996 at 61.

- Id. at 62.

- Id. at 63.

- Lander, Ernest: A History of South Carolina 1865-1960, p. 50. University of South Carolina Press, 1970.

- Simkins 1944 p. 488.

- Id. at 489.

- Miller, Anthony (1977). Coleman Livingston Blease, South Carolina Politician. Graduate Thesis submitted to the University of North Carolina. Found at http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/miller_anthony_1971.pdf.

- Simkins 1944 p. 389.

- Miller 1971 p. 27.

- Stone 1963 p. 63.

- Miller 1971 p. 56.

- Simkins 1944 p. 501.

- Lander, Ernest: A History of South Carolina 1865-1960, pages 51-52. University of South Carolina Press, 1970.

- "Pardoning power in S.C." Post and Courier. Retrieved 2020-12-13.

- "Blease 1911 inaugural address, page 85" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- Stone 1963 p. 57.

- Id. at p. 59.

- Id. at 60.

- Id. at 63.

- Id. at 67.

- Hollis, Daniel, (Jan., 1979), W. Cole Blease: The Years between the Governorship and the Senate, 1915-1924. The South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 80, No. 1, p. 2. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27567534

- Id.

- Hollis, Daniel, (Jan., 1979), W. Cole Blease: The Years between the Governorship and the Senate, 1915-1924. The South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 80, No. 1, p. 3 https://www.jstor.org/stable/27567534

- Hollis 1979, p. 4.

- Id. at 5.

- Id. at pp. 8-9.

- Id. at 17.

- Id. at 16.

- Id.

- Id.

- Id.

- Id.

- "South Carolina Governor - Thomas Gordon McLeod - 1923-1927". www.sciway.net. Retrieved 2020-12-14.

- "Byrnes, James Francis". South Carolina Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2020-12-14.

- Hollis 1979 p. 18.

- "Offers 'Nigger' Poem". Providence Evening Tribune. June 18, 1929. p. 7. Retrieved September 16, 2013.

- "Blease Poetry is Expunged from Record". The Afro-American. 22 June 1929. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- Stanley-Becker, Isaac (2019-06-25). "Who's behind the law making undocumented immigrants criminals? An 'unrepentant white supremacist.'". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2020-12-15.

- Indianapolis Times, Volume 42, Number 105,Indianapolis, 10 September 1930. Retrieved from https://newspapers.library.in.gov/?a=d&d=IPT19300910.1.5&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-------.

- Wire service, “Ex-Senator Dies”, The San Bernardino Daily Sun, San Bernardino, California, Tuesday 20 January 1942, Volume 48, page 1.

Sources

- Adams, James Truslow (1940). Dictionary of American History. Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Burnside, Ronald Dantan (1963). The Governorship of Coleman Livingston Blease of South Carolina, 1911-1915. Indiana University.

- Simkins, Francis Butler (1944). Pitchfork Ben Tillman, South Carolinian (first paperback ed.). Louisiana State University Press. OCLC 1877696

- Simon, Bryant (1996). "The Appeal of Cole Blease of South Carolina: Race, Class, and Sex in the New South". Journal of Southern History. 62 (1): 57–86. doi:10.2307/2211206. JSTOR 2211206.

- Simon, Bryant (1998). A Fabric of Defeat: The Politics of South Carolina Millhands, 1910-1948. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4704-6.

- Stone, Clarence N. (1963). "Bleaseism and the 1912 Election in South Carolina". North Carolina Historical Review. 40: 54–74.

- Hollis, Daniel W. (1978). "Cole L. Blease and the Senatorial Campaign of 1924" (PDF). Proceedings of the South Carolina Historical Association: 53–68. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- Hollis, Daniel W. (1979). "Cole Blease: The Years Between the Governorship and the Senate, 1915-1924". South Carolina Historical Magazine. 80: 1–17.

- Lander, Jr., Ernest McPherson (1970). A History of South Carolina, 1865-1960. University of South Carolina Press. pp. 49–53, 141. ISBN 0-87249-169-2.

- Miller, Anthony Barry (1971). Coleman Livingston Blease. University of North Carolina, Greensboro.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coleman Livingston Blease. |

- SCIway Biography of Coleman Livingston Blease

- United States Congress. "BLEASE, Coleman Livingston (id: B000553)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- NGA Biography of Coleman Livingston Blease

- Moore, William V. "Blease, Coleman Livingston." South Carolina Encyclopedia.

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Martin Frederick Ansel |

Democratic nominee for Governor of South Carolina 1910, 1912 |

Succeeded by Richard Irvine Manning III |

| Preceded by Nathaniel B. Dial |

Democratic nominee for U.S. Senator from South Carolina (Class 2) 1924 |

Succeeded by James F. Byrnes |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Martin Frederick Ansel |

Governor of South Carolina 1911–1915 |

Succeeded by Charles Aurelius Smith |

| U.S. Senate | ||

| Preceded by Nathaniel B. Dial |

United States Senator from South Carolina 1925–1931 |

Succeeded by James F. Byrnes |