Strom Thurmond

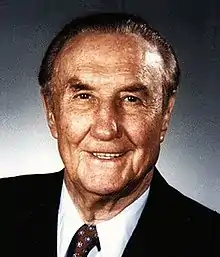

James Strom Thurmond Sr. (December 5, 1902 – June 26, 2003) was an American military officer, attorney, judge and politician who served as a United States senator from South Carolina from 1954 to 2003 and as the 103rd governor of South Carolina from 1947 to 1951. Thurmond served in the United States Senate for 48 years, at first as a Southern Democrat and then, from 1964 onwards, as a Republican. He ran for president in 1948 as the Dixiecrat candidate on a states' rights platform supporting racial segregation. He received 2.4% of the popular vote and 39 electoral votes.

Strom Thurmond | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| President pro tempore of the United States Senate | |

| In office January 20, 2001 – June 6, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Byrd |

| Succeeded by | Robert Byrd |

| In office January 3, 1995 – January 3, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Byrd |

| Succeeded by | Robert Byrd |

| In office January 3, 1981 – January 3, 1987 | |

| Preceded by | Warren Magnuson |

| Succeeded by | John C. Stennis |

| United States Senator from South Carolina | |

| In office November 7, 1956 – January 3, 2003 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas A. Wofford |

| Succeeded by | Lindsey O. Graham |

| In office December 24, 1954 – April 4, 1956 | |

| Preceded by | Charles E. Daniel |

| Succeeded by | Thomas A. Wofford |

| President pro tempore emeritus of the United States Senate | |

| In office June 6, 2001 – January 3, 2003 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Robert Byrd |

| Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee | |

| In office January 3, 1995 – January 3, 1999 | |

| Preceded by | Sam Nunn |

| Succeeded by | John Warner |

| Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee | |

| In office January 3, 1981 – January 3, 1987 | |

| Preceded by | Ted Kennedy |

| Succeeded by | Joe Biden |

| 103rd Governor of South Carolina | |

| In office January 21, 1947 – January 16, 1951 | |

| Lieutenant | George Bell Timmerman Jr. |

| Preceded by | Ransome Judson Williams |

| Succeeded by | James F. Byrnes |

| Member of the South Carolina Senate from the Edgefield County district | |

| In office January 10, 1933 – January 14, 1938 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Greneker |

| Succeeded by | William Yonce |

| Personal details | |

| Born | James Strom Thurmond December 5, 1902 Edgefield, South Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | June 26, 2003 (aged 100) Edgefield, South Carolina, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic (until 1964) Republican (1964–2003) |

| Other political affiliations | Dixiecrat (1948) |

| Spouse(s) | Jean Crouch

(m. 1947; died 1960)Nancy Moore (m. 1968) |

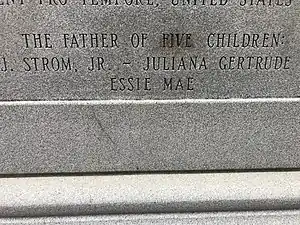

| Children | 5, including Essie, Strom Jr. and Paul |

| Education | Clemson University (BS) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1924–1964[1] |

| Rank | |

| Unit | United States Army Reserve |

| Battles/wars | World War II • Normandy Campaign |

| Awards | Legion of Merit (2) Bronze Star (with valor) Purple Heart World War II Victory Medal European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal Order of the Crown (Belgium) Croix de Guerre (France) |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

U.S. Senator from South Carolina Legacy

|

||

A staunch opponent of Civil Rights legislation in the 1950s and 1960s, Thurmond conducted the longest speaking filibuster ever by a lone senator, at 24 hours and 18 minutes in length, in opposition to the Civil Rights Act of 1957.[2] In the 1960s, he voted against the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Despite his support for segregation, Thurmond always insisted he was not a racist, but a supporter of States‘ Rights and an opponent of excessive federal authority-which he attributed to Communist agitators.[3] Thurmond switched parties for a second time in 1964, saying the Democratic Party no longer represented people like him and subsequently endorsed the Republican presidential candidate, Barry Goldwater who was also opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[4][5]

By the 1970s, Thurmond had started to moderate his stance on race, but continued to defend his prior support for segregation on the basis of states' rights and Southern society at the time.[6] He never fully renounced his earlier positions.[7][8]

Thurmond thrice served as President pro tempore of the United States Senate, chaired the Senate Judiciary Committee from 1981 to 1987 and the Senate Armed Services Committee from 1995 to 1999. He left office in 2003 as the only member of either chamber of Congress to reach the age of 100 while still in office, and as the oldest-serving and longest-serving senator in U.S. history (although he was later surpassed in the latter by Robert Byrd and Daniel Inouye).[9] Thurmond holds the record as the longest-serving member of the Senate. At 14 years, he was also the longest-serving Dean of the United States Senate in political history.

Early life and education

James Strom Thurmond was born on December 5, 1902, in Edgefield, South Carolina, the son of Eleanor Gertrude (née Strom; 1870–1958) and John William Thurmond (1862–1934), a lawyer. His ancestry included English and German.[10]

When Thurmond was five, his family moved into a larger home where the Thurmonds owned about six acres of land, and where John Thurmond thought his sons could learn more about farming. Thurmond had the ability to ride ponies, horses, and bulls from an early age and his home was frequently visited by congressmen, senators, and judges who would follow his father back to the house. At six years old, Thurmond had an encounter with South Carolina Senator Benjamin Tillman, who questioned why he would not shake his hand when the two were introduced to each other by Thurmond's father. Thurmond remembered the handshake as the first political skill he had learned, and continued the pattern of greeting with a handshake throughout his career.[11]

He attended Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina (now Clemson University), graduating in 1923.[12]

In 1925, at the age of 22, Thurmond had an affair with Carrie Butler, his family's teenage African-American housekeeper. In 2003, the Thurmond family confirmed that Thurmond fathered a mixed-race daughter named Essie Mae Washington with Butler.[13][14]

Early career

After college, Thurmond worked as a farmer, teacher and athletic coach until 1929, when at age 27 he was appointed as Edgefield County's superintendent of education, serving until 1933.

In 1930, Thurmond was admitted to the South Carolina bar.[12] He was appointed as the Edgefield Town and County attorney, serving from 1930 to 1938. In 1933, Thurmond was elected to the South Carolina Senate, serving there until 1938, when he was elected to be a state circuit judge.

Thurmond supported Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1932 presidential election. Thurmond favored Roosevelt's argument that the federal government could be used to assist citizens in the daily plights brought on by the Great Depression. Thurmond raised money for Roosevelt and following his victory, traveled to Washington to attend Roosevelt's inauguration.[15]

Thurmond increased in notability after becoming involved in the middle of a dispute between the Timmermans and Logues. In November 1941, officers arrived at the Logue family home to arrest Sue Logue and her brother-in-law for their hiring of the hit man who murdered Davis Timmerman. George Logue and Fred Dorn ambushed the officers after they were allowed entry into the home, the sheriff and deputy both being fatally wounded by the duo. Thurmond, who learned of the shooting while attending a morning church service, became concerned of further violence and drove to the home. On arriving, he removed his jacket and vest while turning his pockets inside out to show that he was without a weapon, then walked inside the home and confronted a Logue family friend who had aimed a shotgun at him. Sue Logue was convinced to surrender after Thurmond promised he would personally see her safely past the angry mob that had assembled outside following the murders. His act was widely reported across the state in the following days. Cohodas wrote that the incident increased public perception of Thurmond as a determined and gritty individual and contributed to his becoming a political celebrity within the state.[16]

World War II

.jpg.webp)

In 1942, at 39, after the U.S. formally entered World War II, Judge Thurmond resigned from the bench to serve in the U.S. Army, rising to lieutenant colonel. In the Battle of Normandy (June 6 – August 25, 1944), he landed in a glider attached to the 82nd Airborne Division. For his military service, Thurmond received 18 decorations, medals and awards, including the Legion of Merit with Oak Leaf Cluster, Bronze Star with Valor device, Purple Heart, World War II Victory Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, Belgium's Order of the Crown and France's Croix de Guerre{cn}.

During 1954–55, Thurmond was president of the Reserve Officers Association. He retired from the U.S. Army Reserve with the rank of major general{cn}.

Governor of South Carolina

Running as a Democrat in a virtually one-party state, Thurmond was elected Governor of South Carolina in 1946, largely on the promise of making state government more transparent and accountable by weakening the power of a group of politicians from Barnwell,[17] which Thurmond dubbed the Barnwell Ring, led by House Speaker Solomon Blatt.

Many voters considered Thurmond a progressive for much of his term, in large part due to his influence in gaining the arrest of the perpetrators of the lynching of Willie Earle. Though none of the men were found guilty by an all-white jury in a case where the defense called no witnesses,[18] Thurmond was congratulated by the NAACP and the ACLU for his efforts to bring the murderers to justice.[19]

In, 1949, Thurmond oversaw the opening of Camp Croft State Park,[20] and in November he was unanimously elected Chairman of the Southern Governors Conference.[21]

Run for President

In the 1948 Presidential Election, Thurmond ran for president as a third party candidate for States' Rights Democratic Party, which was formed by White southern Democrats who split from the national party over the threat of federal intervention in state affairs regarding segregation and Jim Crow. Thurmond's supporters took control of the Democratic Party in the Deep South. President Truman was not included on the presidential ballot in Alabama because that state's Supreme Court ruled void any requirement for party electors to vote for the national nominee.[22] Thurmond stated that Truman, Thomas Dewey and Henry A. Wallace would lead the U.S. to totalitarianism.[23] Thurmond called civil rights initiatives dangerous to the American constitution and making the country susceptible to communism in the event of their enactment,[24] challenging Truman to a debate on the issue.[25] Thurmond carried four states and received 39 electoral votes, but was unable to stop Truman's re-election.

During the campaign, Thurmond said the following in a speech met with loud cheers by his assembled supporters: ![]() listen

listen

I wanna tell you, ladies and gentlemen, that there's not enough troops in the army to force the Southern people to break down segregation and admit the Nigra race into our theaters, into our swimming pools, into our homes, and into our churches.[lower-alpha 1][6]

Thurmond quietly distanced himself from the States' Rights Party in the aftermath of the 1948 campaign, despite saying shortly before its conclusion that the party would continue as opposition to the national Democratic Party. After Thurmond missed a party meeting in December of that year in which the States' Rights Democratic Party created a state's rights institute in Washington, columnist John Temple Graves, disappointed in Thurmond's absence, opined that his campaign had been the best argument that the States' Rights Party was a national movement centered around the future of liberty and restrained government. Thurmond concurrently received counsel from Walter Brown and Robert Figgs to break from the party and seek reclaiming credentials that would validate him in the minds of others as a liberal. Biographer Joseph Crespino observed that Thurmond was aware that he could neither completely abandon the Democratic Party as it embraced the civil rights initiative of the Truman administration nor let go of his supporters within the States' Rights Party, whom he courted in his 1950 campaign for the Senate.[26]

Concurrently with Thurmond's discontent, former Senator and Secretary of State James F. Byrnes began speaking out against the Truman administration's domestic policies. Walter Brown sought to link the 1950 gubernatorial campaign of Byrnes with the Thurmond Senate campaign as part of a collective effort against President Truman, this effort appeared to have been a success. Byrnes indirectly criticized Thurmond when asked by a reporter in 1950 about his governing if elected South Carolina Governor, saying he would not waste time "appointing colonels and crowning queens"; the remark geared toward the image of Thurmond as not serious and conniving. Brown wrote to Thurmond that the comment was a death to any potential alliance between the two politicians. Thurmond and his wife are described as looking "like they had been shot" when reading the Byrnes quotation in the newspaper.[27]

Early runs for Senate

According to the state constitution, Thurmond was barred from seeking a second consecutive term as governor in 1950, so he mounted a Democratic primary challenge against first-term U.S. Senator Olin Johnston.[28] On May 1, Thurmond's Senate campaign headquarters opened in Columbia, South Carolina with Ernest Craig serving as campaign leader and George McNabb in charge of public relations, both were on leave from their state positions in the governor's office.[29] In the one-party state of the time, the Democratic primary was the only competitive contest. Both candidates denounced President Truman during the campaign. Johnston defeated Thurmond 186,180 votes to 158,904 votes (54% to 46%) in what would be Thurmond's first and only state electoral defeat.

Senate Career

In 1952, Thurmond endorsed Republican Dwight Eisenhower for the Presidency, rather than the Democratic nominee Adlai Stevenson.

First Term

The incumbent U.S. Senator, Burnet R. Maybank, was unopposed for re-election in 1954, but he died in September of that year, two months before Election Day. Democratic leaders hurriedly appointed state Senator Edgar A. Brown, a member of the Barnwell Ring, as the party's nominee to replace Maybank. The Brown campaign was managed by future Governor John C. West. In a state where the Democratic nomination was tantamount to election, many criticized the party's failure to elect a candidate by a primary vote. Thurmond mounted a write-in campaign. At the recommendation of Governor James Byrnes, Thurmond campaigned on the pledge that if he won, he would resign in 1956 to force a primary election which could be contested. Thurmond won the 1954 election overwhelmingly, becoming the first person to elected to the U.S. Senate as a write-in candidate against ballot-listed opponents. It has only been repeated once, in 2010, by Lisa Murkowski (alongside whom Thurmond had served for two weeks). As promised, in 1956 Thurmond resigned to run in the party primary, which he won. Afterward, he was repeatedly elected to the U.S. Senate by state voters until his retirement 46 years later.

In January 1955, Thurmond stated that federal encroachment on states' rights was among the biggest threats to American life and violated the Constitution. Thurmond spoke of the importance of education, saying it "should be a primary duty of the states just as national defense is a primary obligation of the federal government."[30]

In July 1955, Thurmond backed the Eisenhower Administration‘s plan for an expanded military reserve law, including peacetime officers receiving compulsory training. Thurmond argued the bill would strengthen Eisenhower during the Geneva Big Four summit and voiced stated his opposition to an alternate plan proposed by Richard Russell, which would abolish compulsory feature in addition to adding a bonus of $400 to males forgoing active duty, saying he did not believe patriotism could be purchased.[31] In November, Chairman of the U.S. Tariff Commission, Edgar Brossard told Thurmond his position on domestic wool protection would be a factor in negotiating the next tariff agreement.[32]

| Wikisource has the text of Thurmond’s filibuster: |

Congress rejected a civil rights bill in 1956, Eisenhower introducing a modest version the following year meant to impose an expansion of federal supervision of integration in Southern states.[33] In an unsuccessful attempt to derail the bill's passage,[34] Thurmond spoke for a total of 24 hours and 18 minutes against the bill, the longest filibuster ever conducted by a single senator.[35] Other Southern senators, who had agreed as part of a compromise not to filibuster this bill, were upset with Thurmond because they thought his defiance made them look incompetent to their constituents.[36] Alternatively, Thurmond was pressured by South Carolina Governor George Bell Timmerman Jr., an opponent of the pro-civil rights stances imposed by the Eisenhower administration, Timmerman wanting Thurmond to take part in a filibuster.[37] By then, Thurmond had already become known as one of the most vocal opponents of civil rights legislation.[38] Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1957 on August 29.[39]

In January 1959, the Senate held a debate over changing the rules to curb filibusters, Thurmond expressed the view that the Senate return to the rule prior to 1917, when there were no regulations on the time for debate.[40]

Brown v. Board of Education

Thurmond co-wrote the first version of the Southern Manifesto, stating disagreement with the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, that desegregated public schools.[41] Thurmond was part of the group of Southern senators that met continually in the office of Russell in early 1956 and shared a commonality of being dispirited with Brown v. Board of Education.[42]

Further Attempts at Obstruction

In February 1960, Thurmond asked for a quorum call that would produce at least half the membership of the Senate, the call being seen as one of the delay tactics employed by Southerners during the meeting. 51 senators assembled, allowing for the Senate to adjourn in spite of Thurmond's calls for another quorum call. Thurmond afterward denied his responsibility in convening the Saturday session, attributing it to Democrat Lyndon B. Johnson and opining that those insistent on passing a civil rights bill should be around during discussions on the matter.[43] During his filibuster, Thurmond relied on the book The Case for the South, written by W. D. Workman Jr. Thurmond had known the author for fifteen years as Workman had covered both Thurmond's tenure as South Carolina governor and his presidential campaign, in addition to having served in the military unit Thurmond had organized in Columbia, and having turned down an offer by Thurmond to serve as his Washington office press secretary. The Case for the South, described in 2013 by Loyola history professor and author Elizabeth Shermer as "a compendium of segregationist arguments that hit all the high points of regional apologia", was sent by Thurmond to each of his Senate colleagues and then-vice president Richard Nixon.[44]

Second Term

On account of Kennedy’s known support for Civil Rights, Thurmond refused to support the Democrat nominee in The 1960 Presidential Election. Following Kennedy’s victory, Thurmond loudly voiced the view he’d be expelled from the Senate Democratic Caucus in retaliation.[45]

Kennedy administration

The 87th United States Congress began without a move to remove Thurmond from the Senate Democratic Caucus, in spite of Thurmond's predictions to the contrary.[46] An aide for Senator Joseph S. Clark Jr. said there was never an intention to pursue recourse against Thurmond, though in his opinion Thurmond should no longer be a member of the party.[47]

In February 1961, Thurmond stated his support for imposing quotas per country and category on textile imports; noting that the same practice was being imposed by other countries. He added that American industry would be destroyed by government subsidies that would convert the textile industry to other fields.[48] He later opposed legislation that "would give the president unprecedented authority to lower or wipe out tariff wall [and] would provide for the first time broad government relief to industries and workers", the only Democrat to do so.[49]

In May, when the Senate debated Kennedy‘s public school aid bill, Thurmond proposed an amendment prohibiting the government from barring segregated schools from receiving loans or grants.[50] In August, Thurmond formally requested the Senate Armed Services Committee vote on whether to vote for "a conspiracy to muzzle military anti-Communist drives." The appearance prompted the cancellation of another public appearance in Fort Jackson, as Thurmond favored marking his proposal with his presence, and his request for a $75,000 committee study was slated for consideration.[51] In November, Thurmond went on a five-day tour of California. At a news conference, Thurmond stated that President Kennedy had lost support in the South due to the formation of the National Relations Boards, what he called Kennedy's softness on communism, and an increase in military men being muzzled for speaking out against communism.[52] Thurmond held resentment toward NBC for its lack of coverage of his military muzzling claims.[53]

In December 1961, Thurmond addressed the Arkansas American Legion conference in Little Rock. Thurmond claimed he had been told that the State Department was preparing "a paper for the turning over of our nuclear weapons to the United Nations."[54]

In January 1962, Thurmond charged the military speeches' censorship with having proven State Department officials sold U.S. leadership on the country not wanting to win the Cold War.[55][56] That month, Senate investigators into the military censoring disclosed having obtained documents not given to them by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. Thurmond stated the evidence was obtained through checking with the individuals censoring, describing them as just taking orders. He added that the issue of censoring had predated the Kennedy administration, though charged the incumbent executive branch with having increased its practice.[57] The committee was ended on June 8.[58] In May, Thurmond was part of a group of Senate orators headed by John C. Stennis who expressed opposition to the Kennedy administration's literacy test bill, arguing that the measure was in violation of states' rights as defined by the Constitution.[59] After the Supreme Court ruled state composed prayer in public schools was unconstitutional, Thurmond urged Congress to take steps to prevent the Court from making similar decisions.[60]

In September 1962, Thurmond called for an invasion of Cuba.[61] In a February Thurmond stated that "the brush curtain around Cuba is a formidable Soviet strategic military base" and estimated between 30,000 and 40,000 Cuban troops were under the leadership of a Soviet general. Hours after the statement was made public, a Pentagon official disputed his claims as being "at wide variance with carefully evaluated data collected by U.S. intelligence" and called for Thurmond to release his proof to the Defense Department.[62]

After Kennedy sent Congress his civil rights bill, Thurmond's opposition was clear and immediate.[63] Later that month, Thurmond accused radio and television networks of supporting the views espoused by the NAACP, sparking a dispute with Rhode Island Senator John Pastore.[64] In the weeks leading up to the March on Washington, Thurmond delivered a Senate floor speech,[65] accussing the march's organizer Bayard Rustin of "being a communist, a draft dodger and a homosexual." Rustin biographer John D'Emilio said these remarks unintentionally gave Rustin further credit in the Civil Rights Movement: "Because no one could appear to be on the side of Strom Thurmond, he created, unwittingly, an opportunity for Rustin's sexuality to stop being an issue."[66] Rustin denied Thurmond's charges on August 15.[67]

During Paul Nitze‘s nomination hearing for Secretary of the Navy, Thurmond was noted for asking "rapid fire questions” on military action and focusing on Nitze's participation as a moderator in the 1958 National Council of Churches conference.[68] Along with Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater, Thurmond delayed the Nitze nomination.[69] In spite of Thurmond voting against him,[70]

Johnson administration

The day after the Nitze vote, President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas.[71][72] Thurmond expressed the view that a conspiracy would be found by investigators to have been responsible for JFK's death.[73] Vice President Lyndon Johnson ascended to the presidency, beginning a campaign for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 which angered white segregationists. These laws ended segregation and committed the federal government to enforce voting rights of citizens by the supervision of elections in states in which the pattern of voting showed black people had been disenfranchised. Many Democrats strongly opposed these laws, including Senator Robert Byrd, who filibustered the Civil Rights Act for 14 hours and 13 minutes on June 9 and 10, 1964.

During the signing ceremony for the Civil Rights Act, President Johnson nominated LeRoy Collins as the first Director of the Community Relations Service.[74] Subsequently, Thurmond reminded Collins of his past support for segregation and implied that he was a traitor to the South, Thurmond having particular disdain for an address by Collins the previous winter in which he charged southern leaders with being harsh and intemperate.[75] Thurmond also suggested that Collins had sought to fault southern leaders for President Kennedy's assassination.[75] Thurmond was the only senator to vote against Collins' nomination being sent to the Senate, and later one of eight senators to vote against his nomination in the chamber.[76]

Thurmond stated that his opposition to the Voting Rights Act was due to not favoring its authorization of the federal government to determine the processes behind how statewide elections are conducted and insisted he was not opposed to black voter turnout.[77]

In 1965, L. Mendel Rivers became chairman of the House Armed Services Committee. Commentator Wayne King credited Thurmond's involvement with Rivers as giving Rivers' district "an even dozen military installations that are said to account for one‐third to one‐half of the jobs in the area."[78]

In 1966, former governor Ernest "Fritz" Hollings won South Carolina's other Senate seat in a special election. He and Thurmond served together for just over 36 years, making them the longest-serving Senate duo in American history. Thurmond and Hollings had a very good relationship, despite their often stark philosophical differences. Their long tenure meant their seniority in the Senate gave South Carolina clout in national politics well beyond its modest population.

On January 17, 1967, Thurmond was appointed to the Senate Judiciary subcommittee on Constitutional Rights.[79] In March, as the Senate passed an endorsement of the United States antiballistic missile system, Thurmond engaged in a back and forth with Joseph Clark after Clark mentioned that Charleston, South Carolina would be included in the Pentagon's list of twenty-five American cities that would get priority in their antimissile protection and attributed this to the influence of Chairman of the House Armed Services Committee L. Mendel Rivers. Thurmond then demanded a rule that would bar senators from being able to disparage members of the House of Representatives in addition to preventing them from speaking and having to remain seated. Clark argued that the rule did not apply to him since he had finished speaking, Thurmond rebutting, "If the senator is not going to be man enough to take his medicine, then let him go." Thurmond then won unanimous approval to have Clark's remarks removed from the record.[80] In July, after the 1967 USS Forrestal fire, Thurmond wrote of his conviction that the outbreak had been precipitated by communists.[81] In September, Thurmond warned against enacting any of the three proposed Panama Canal treaties, which he said could lead to Communist control of the waterway if enacted.[82] The month also saw Thurmond note the belief by some individuals that working had become an outdated idea that was destined to become extinct with the rise of technology and voiced his disagreement with the notion.[83]

In 1969, Time ran a story accusing Thurmond of receiving "an extraordinarily high payment for land". Thurmond responded to the claim on September 15, saying the tale was a liberal smear intended to damage his political influence,[84] later calling the magazine "anti-South".[85] At a news conference on September 19, Thurmond named Executive Director of the South Carolina Democratic Party Donald L. Fowler as the individual who had spread the story, a charge that Fowler denied.[86] Thurmond decried the Supreme Court opinion in Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education (1969), which ordered the immediate desegregation of schools in the American South.[87] This had followed continued Southern resistance for more than a decade to desegregation following the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional. Thurmond praised President Nixon and his "Southern Strategy" of delaying desegregation, saying Nixon "stood with the South in this case".[87]

1964 presidential election and party switch

On September 16, 1964, Thurmond confirmed he was leaving the Democratic Party to work on the presidential campaign of Barry Goldwater, charging the Democrats with having "abandoned the people" and having repudiated the U.S. Constitution as well as providing leadership for the eventual takeover of the U.S. by socialistic dictatorship. He called on other Southern politicians to join him in bettering the Republican Party.[88] Thurmond joined Goldwater in campaigning through Louisiana later that month, telling reporters that he believed Goldwater could carry South Carolina in the general election along with other southern states.[89] Goldwater won South Carolina with 59% of the vote compared to President Lyndon Johnson's 41%[90][91]

On January 15, 1965, Senate Republicans voted for committee assignments granting Thurmond the ability "to keep at least some of the seniority power he had gained as a Democrat."[92]

Supreme Court

In June 1967, Johnson nominated Thurgood Marshall to be the first African-American Justice on the Supreme Court.[93] Along with Sam Ervin, Spessard Holland, and James Eastland, Thurmond was one of four senators noted for calling Marshall a "Constitutional iconoclast" in Senate debate.[94] Thurmond questioned Marshall for an hour "on fine points of constitutional law and history", the move being seen as critics of the nomination turning their inquiry to the subject of Marshall's legal experience.[95] Thurmond stated that Marshall had evaded questions on his legal principles during committee hearings and in spite of his extensive experience, had displayed an ignorance of basic constitutional principles.[96] Marshall was still confirmed by the Senate at the end of that month.[97]

In 1968, Chief Justice Earl Warren decided to retire, Johnson subsequently nominated Abe Fortas to succeed him.[98] On the third day of hearings, Thurmond questioned Fortas over Mallory v. United States (1957), a case taking place before Fortas's tenure, but for which he was nonetheless held responsible by Thurmond.[99] Thurmond asked Fortas if the Supreme Court decision in the Mallory v. United States case was an encouragement of individuals to commit serious crimes such as rape and if he believed in "that kind of justice", an inquiry that shocked even the usually stoic Fortas.[99] Thurmond displayed sex magazines, which he called "obscene, foul, putrid, filthy and repulsive", to validate his charges that Supreme Court rulings overturning obscenity convictions had led to a large wave of hardcore pornography material. Thurmond stated that Fortas had backed overturning 23 of the 26 lower court obscenity decisions.[100] Thurmond also arranged for the screening of explicit films that Fortas had purportedly legalized, to be played before reporters and his own Senate colleagues.[101] In September, Vice President Hubert Humphrey spoke of a deal made between Thurmond and Nixon over Thurmond's opposition to the Fortas nomination.[102] Both Nixon[103] and Thurmond denied Humphrey's claims, Thurmond saying that he had never discussed the nomination with Nixon while conceding the latter had unsuccessfully tried to sway him from opposing Fortas.[104]

In December 1968, Thurmond stated that President Johnson had considered calling for a special session of Congress to nominate Arthur J. Goldberg as Chief Justice before becoming convinced there would be problems during the process.[105]

In an April 25, 1969 Senate floor speech, Thurmond stated that The New York Times "had a conflict of interest in its attacks on Otto F. Otepka's appointment to the Subversive Activities Control Board."[106] On May 29, Thurmond called for Associate Justice William O. Douglas to resign over what he considered political activities.[107] Douglas remained in office for another six years.[108] In the latter part of the year, President Nixon nominated Clement Haynsworth for Associate Justice.[109][110] This came after the White House consulted with Thurmond throughout all of July, as Thurmond had become impressed with Haynsworth following their close collaboration. Thurmond wrote to Haynsworth that he had worked harder on his nomination than any other that had occurred since his Senate career began.[111] The Haynsworth nomination was rejected in the Senate.[112] Years later, at a March 1977 hearing, Thurmond told Haynsworth, "It's a pity you are not on the Supreme Court today. Several senators who voted against you have told me they would vote for you if they had it to do again."[113]

1968 presidential election

On October 23, 1966, Thurmond stated that President Johnson could be defeated in a re-election bid by a Republican challenger since the candidate was likely to be less obnoxious than the president.[114]

Thurmond was an early supporter of a second presidential campaign by Nixon, his backing coming from the latter's position on the Vietnam War.[115] Thurmond met with Nixon during the Republican primary and promised he would not give in to the "depredations of the Reagan forces."[116] At the 1968 Republican National Convention in Miami Beach, Florida, Thurmond, along with Mississippi state chairman Clarke Reed, former U.S. Representative and gubernatorial nominee Howard Callaway of Georgia, and Charlton Lyons of Louisiana held the Deep South states solidly for Richard M. Nixon despite the sudden last-minute entry of Governor Ronald Reagan of California into the race. Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York was also in the race but having little effect. In the fall 1968 general election, Nixon won South Carolina with 38 percent of the popular vote and gained South Carolina's electoral votes. With the segregationist Democrat George Wallace on the ballot, the South Carolina Democratic voters split almost evenly between the Democratic Party nominee, Hubert Humphrey, who received 29.6 percent of the total vote, and Wallace, who received 32.3 percent. Other Deep South states swung to Wallace and posted weak totals for Nixon.

Thurmond had quieted conservative fears over rumors that Nixon planned to ask either liberal Republicans Charles Percy or Mark Hatfield to be his running mate. He informed Nixon that both men were unacceptable to the South for the vice-presidency. Nixon ultimately asked Governor Spiro Agnew from Maryland—an acceptable choice to Thurmond—to join the ticket.

During the general election campaign, Agnew stated that he did not believe Thurmond was a racist when asked his opinion on the matter. Clayton Fritchey of the Lewiston Evening Journal cited Agnew's answer over the Thurmond question as an example of the vice presidential candidate not being ready for the same "big league pitching" Nixon had shown during the 1952 election cycle.[117] Thurmond participated in a two-day tour of Georgia during October, saying that a vote for American Independent Party candidate George Wallace was a waste, adding that Wallace could not win nationally and would only swing the election in favor of Democratic nominee Hubert Humphrey by having the Democratic-majority House of Representatives select him in the event none of the candidates received enough electoral votes to win the presidency outright. Thurmond also stated that Nixon and Wallace had similar views and predicted Nixon would carry Virginia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Florida, Texas and Tennessee.[118] Nixon carried each of these states with the exception of Texas.[119]

1966 re-election campaign

Thurmond faced no opposition in the Republican primary and was renominated in March 1966.[120] Thurmond competed against Bradley Morrah Jr. in the general election campaign.[121] Morrah avoided direct charges against Thurmond's record and generally spoke of his own ambitions in the event he was elected.[122] He referred to Thurmond's time in the Senate as being ineffective.[123]

Thurmond won election with 62.2 percent of the vote (271,297 votes) to Morrah's 37.8 percent (164,955 votes).

1970s

.jpg.webp)

Thanks to his close relationship with the Nixon administration, Thurmond was able to deliver a great deal of federal money, appointments and projects to his state. With a like-minded president in the White House, Thurmond became a very effective power broker in Washington. His staffers said his goal was to be South Carolina's "indispensable man" in Washington, D.C.

In the 1970 gubernatorial election, Thurmond's preferred candidate, U.S. Representative Albert W. Watson, was defeated by his more moderate opponent, Democrat John C. West, the outgoing lieutenant governor, who had opposed Thurmond's initial write-in election to the Senate. Watson had defected to the Republicans in 1965, the year after Thurmond's own bolt, and had been politically close to the senator. Watson lost mainly after several Republican officials in South Carolina shied away from him because of his continuing opposition to civil rights legislation. Watson's loss caused Thurmond slowly to moderate his own image in regard to changing race relations.

In 1970, Thurmond urged Nixon to nominate another South Carolina Republican convert, Joseph O. Rogers Jr., to a federal judgeship; he had been the party's unsuccessful 1966 gubernatorial nominee against the Democrat Robert Evander McNair. At the time Rogers was the U.S. Attorney in South Carolina. When his judicial nomination dragged on, Rogers resigned as U.S. attorney and withdrew from consideration. He blamed the Nixon administration, which he and Thurmond had helped to bring to power, for failure to advance his nomination in the Senate because of opposition to the appointment from the NAACP.[124]

On February 22, 1970, Thurmond delivered an address at Drew University defending Julius Hoffman,[125] a judge who had drawn controversy for his role in the Chicago Seven trial.[126][127] Protestors threw marshmallows at Thurmond in response to the speech, Thurmond telling the hecklers that they were cowards for not hearing what he had to say.[128]

In February 1971, Senate Republicans voted unanimously to bestow Thurmond full seniority, the vote being seen as "little more than a gesture since committee assignments are the major item settled by seniority and Senator Thurmond has his."[129] Later that month, when Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy visited South Carolina to deliver an address in Charleston, Thurmond gave remarks to the Charleston Chapter of the Air Force Association several hours earlier, mocking Kennedy for the Chappaquiddick incident. Thurmond noted that Brigadier General Thomas Kennedy's wife was named Joan, the same first name as Joan Bennett Kennedy, the senator's wife. He added that the Joan married to the Brigadier General had a husband who was a better driver.[130]

In May 1971, a Thurmond spokesman confirmed that Thurmond had asked President Nixon to appoint Albert Watson to the United States Court of Military Appeals.[131]

During this period, the NSA reportedly had been eavesdropping on Thurmond's conversations, using the British part of the ECHELON project.[132]

On June 2, Thurmond attended the launch of the USS L. Mendel Rivers (SSN-686), during which he stated that the Soviet Union was building three submarines for every one built by the U.S. and called for American submarine construction to be accelerated.[133][134] At a July 1973 hearing, Thurmond suggested that the decision made by former Air Force Major Hal M. Knight to testify had to do with Knight's lack of advancement. Knight responded that he did not take an oath to support the military but instead the constitution.[135]

In the 1976 Republican primary, President Ford faced a challenge from former California Governor Ronald Reagan, who selected Richard Schweiker as his running mate.[136] Though Thurmond backed Reagan's candidacy, he, along with North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms, led efforts to oust Schweiker from the ticket.[137] During the subsequent general election, Thurmond appeared in a campaign commercial for incumbent U.S. President Gerald Ford in his race against Thurmond's fellow Southerner, former Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter. In the commercial, Thurmond said Ford (who was born in Nebraska and spent most of his life in Michigan) "sound[ed] more like a Southerner than Jimmy Carter".[138] After President-elect Carter nominated Theodore C. Sorensen as his choice to become Director of the Central Intelligence Agency, Thurmond expressed reservations[139] and fellow Senator Jake Garn said he believed Thurmond would not vote for the nomination.[140] Sorensen withdrew from consideration days later, before a vote could be had.[141][142]

A short time after Mississippian Thad Cochran entered the Senate in late 1978, Thurmond gave him advice on how to vote against bills intended to aid African-Americans but not lose their voting support: "Your black friends will be with you, if you be sure to help them with their projects."[143]

Domestic policy

In January 1970, Thurmond asserted that he would work "to reverse the unreasonable and impractical decisions of the Supreme Court", as well as assist with the appointment of "sound judges" and uphold the Nixon administration's position for resumption of tax‐exempt status among all private schools.[144] In April 1970, Thurmond was among a group of Senators who voted in opposition to the popular vote in presidential elections replacing the electoral college as the determining factor in the election's winner.[145] In 1977, Thurmond explained his opposition to the change was due to his belief that using the popular vote was "not true federalism." He advocated that senators not act with haste on the issue.[146] In May, Thurmond stated his support for Joseph O. Rogers Jr. as South Carolina federal district judge.[147] In June, along with Norris Cotton, John J. Williams, and Spessard L. Holland, Thurmond was one of four senators to vote against a 4.8 billion education bill.[148] In a July 17, 1970 Senate floor speech, Thurmond criticized the Nixon administration following the disclosure of Assistant Attorney General Jerris Leonard that 100 lawyers were intended to be sent for the monitoring of school districts at the start of a court ordered school desegregation plan.[149][150] White House counselor Robert H. Finch stated the Senator was reacting to false information and that the administration was "not sending any large augmentation of people into the South."[151] In August, Thurmond was one of eight senators to vote against an appropriation bill $541 million higher than that proposed by President Nixon.[152] In September, Thurmond attended the 10th anniversary meeting of the Young Americans for Freedom at the University of Hartford, delivering a speech on the rise of guerilla warfare in the United States through urban and campus riots and how it could eventually lead to the dissolution of the country. Thurmond stated the riots would have been less likely to occur had more force been used on the part of authorities and the same belief system should have been adapted in American policy toward Vietnam, which he elaborated on by advocating for American forces receiving more resources needed to secure victories.[153] In November, along with fellow southerners James Eastland and Sam J. Ervin Jr., Thurmond was one of three Senators to vote against an occupational safety bill that would establish a federal supervision to oversee working conditions.[154] In December, Thurmond was one of thirty senators to sign a letter to the Interstate Commerce Commission charging the agency with imperiling rail transportation in the United States through ceasing to be a regulatory entity.[155]

In March 1971, Thurmond introduced a bill that if enacted would authorize individuals who chose to continue working after the age of 65 to have the option of no longer paying Social Security taxes. Thurmond said, "A worker 65 or over who wishes to continue paying Social Security taxes in order to qualify for greater benefits in the future remains free to do so."[156] In December, Thurmond delivered a Senate address predicting that Defense Secretary Melvin Laird would "propose one of the biggest defense budgets in history" during the following year.[157]

On February 4, 1972, Thurmond sent a secret memo to William Timmons (in his capacity as an aide to Richard Nixon) and United States Attorney General John N. Mitchell, with an attached file from the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee, urging that British musician John Lennon (then living in New York City) be deported from the United States as an undesirable alien, due to Lennon's political views and activism.[158] The document claimed Lennon's influence on young people could affect Nixon's chances of re-election, and suggested that terminating Lennon's visa might be "a strategy counter-measure".[159] Thurmond's memo and attachment, received by the White House on February 7, 1972, initiated the Nixon administration's persecution of John Lennon that threatened the former Beatle with deportation for nearly five years from 1972 to 1976. The documents were discovered in the FBI files after a Freedom of Information Act search by Professor Jon Wiener, and published in Weiner's book Gimme Some Truth: The John Lennon FBI Files (2000).[159] They are discussed in the documentary film, The U.S. vs. John Lennon (2006). In April, when the Senate Armed Services Committee voted to end the Cheyenne helicopter project with a reduction of $450 million from the Pentagon's weapons programs, Thurmond was the sole Republican senator on the committee to oppose the move to terminate the project.[160] In September, Thurmond and Democrat Mike Gravel introduced legislation intended to increase American fortune in future Olympic Games through the formation of a National Amateur Sports Foundation that would fund both sports facilities and training programs while developing greater cooperation among existing sports organizations. Thurmond stated that the proposed National Amateur Sports Foundation would "work with the present amateur athletic organizations but is in no way an attempt to supplant or assume control over these organizations" while granting "necessary coordination between the various existing organizations who so often in the past have worked at cross purposes."[161]

In March 1973, Thurmond was one of nine Republican senators to vote with the Democratic majority in favor of a measure demanding President Nixon to release the $120 million the Agriculture Department had not used toward water and rural area sewer systems.[162] In April, Thurmond announced a $3 million grant and $700,000 loan from federal agencies for South Carolina with the Farmers Home Administration granting the loan to the Edgefield County Water and Sewer Authority to complete a rural system serving 2,906 residences in addition to businesses in surrounding areas.[163] In June, the Senate Commerce Committee approved the Amateur Athletic Act of 1973, legislation that would form the United States Sports Board while ending the power struggle between the Amateur Athletic Union and the National Collegiate Athletic Association by having the board assume powers of both organizations and function as an independent federal agency that would be assigned with protecting the rights of athletes to participate. Thurmond staffers had joined with staffers of Senators James B. Pearson, Mike Gravel, and Marlow Cook in primarily writing the legislation.[164]

In August 1974, the Senate Appropriations Committee approved a cut of nearly 5 billion in the Defense Department's budget for the current fiscal year, conflicting with President Ford. Thurmond expressed doubt on any major efforts to restore funds being undertaken by Ford administration supporters during the Senate floor debate.[165] In October, Thurmond was one of five senators to sponsor legislation authored by Jesse Helms permitting prayer in public schools and taking the issue away from the Supreme Court which had previously ruled in 1963 that school prayer violated the First Amendment to the United States Constitution through the establishment of a religion.[166]

In January 1975, Thurmond was one of four senators to vote against the creation of a special committee to investigate the Central Intelligence Agency, Federal Bureau of Investigation, and other government agencies intended to either gather intelligence or enforce the law.[167]

In January 1976, the Senate voted in favor of expanding American fishing jurisdiction by 200 miles, a bill that Thurmond opposed. Thurmond was successful in implementing an amendment, which passed 93 to 2, postponing the date of its effect by a year. In consulting with President Ford by telephone, the latter confirmed to Thurmond that the added period brought about by his amendment would see him sign the bill in the interim.[168] In October, Thurmond was informed of President Ford's intent to sign the Congaree National Park bill, authorizing the purchase of 15,200 acres of Beidler Tract. Thurmond said it would be "a great day for all those who have worked so long and hard to see that the Congaree forest will be saved."[169]

In January 1977, Thurmond introduced a bill prohibiting American uniformed military forces having unionization, the measure earning the support of thirty-three senators. Thurmond wrote, "If military unions have proved irresponsible in other countries we can hardly permit them to be organized in the United States on the flimsy hypothesis that they may possibly be more responsible here."[170] In April, Thurmond supported legislation forming a stringent code of ethics in the Senate with the intention of assisting with the restoration of public confidence in Congress.[171] In May, Thurmond made a joint appearance with President Carter in the Rose Garden in a show of bipartisan support for proposed foreign intelligence surveillance legislation. Thurmond stated he had become convinced the legislation was needed from his service on the Armed Services Committee, the Judiciary Committee and the Intelligence Committee the previous year and lauded the bill for concurrently protecting the rights of Americans, as a warrant would have to be obtained from a judge in order to fulfill any inquiries.[172] In July, the Senate voted against terminating the Clinch River Breeder Reactor Project. Arguing in favor of the plant, Thurmond stated that Gulf Oil, Shell Oil, and Allied Chemical gathered "the best brains" in the U.S. to head the plant in anticipation of Gerald Ford's election, and questioned whether it was honorable to discontinue the plant simply because Ford had left office.[173] In August, Thurmond cosponsored legislation providing free prescription drugs to senior citizens with Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy. The bill would cover 24 million Americans over the age of 65 and was meant to augment the Medicare program with prescription drugs being paid for and given to individuals not hospitalized.[174]

In June 1978, Thurmond and Republican Jesse Helms were two senators named by an environmental group as part of a congressional "Dirty Dozen" that the group believed should be defeated in their re-election efforts due to their stances on environmental issues; membership on the list was based "primarily on 14 Senate and 19 House votes, including amendments to air and water pollution control laws, strip‐mining controls, auto emissions and water projects."[175] In August, Thurmond joined other senators in voting for the District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment, which would have given the District of Columbia full representation in Congress along with participation in the Electoral College.[176] He was one of the earliest supporters of its enactment and participated in floor debates on the measure. The Washington Post noted that Thurmond and other southern senators supporting the measure "provided one of the most vivid illustrations to date of the new reality of politics in the South, where the number of black voters has doubled in the past 13 years since the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965."[177] The amendment was ratified by sixteen states before meeting its expiration.

In January 1979, Ted Kennedy, in his new position as Senate Judiciary Committee chairman, terminated the blue slip system, which had previously allowed senators to veto prospective federal judgeship nominees from his or her state. Nevada Senator Paul Laxalt read a statement from Thurmond in which the latter presumed "that the committee will honor the blue slip system that has worked so well in the past".[178] In March, the Carter administration made an appeal to Congress for new powers to aid with the enforcement of federal laws as it pertains to housing discrimination. Thurmond refused to back the administration as he charged it with "injecting itself in every facet of people's lives" and said housing disputes should be settled in court.[179] In April, during a congressional hearing attended by Coretta Scott King and other witnesses in favor of establishing the birthday of Martin Luther King Jr. as a national holiday, Thurmond stated that the Civil Service Commission had estimated that enacting the holiday would cost the government $22 million to cover pay for federal employees. Thurmond furthered that taxpayers would be forced to pay $195 million to accommodate the employees. Ted Kennedy responded to Thurmond by saying that the estimates were not factoring in the revenue that could be generated from sales on the proposed holiday.[180] In July, after the Carter administration unveiled a proposed governing charter for the FBI, Thurmond stated his support for its enactment, his backing being seen by the New York Times as an indication that the governing charter would face little conservative opposition.[181] In September, the Senate approved Bailey Brown as Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. The nomination was one of the few votes in which Thurmond and Ted Kennedy joined forces in confirming and Thurmond supported an opinion by Kennedy on what the latter hoped would be the precedent for judicial nominees: "It is inadvisable for a nominee for a Federal judgeship to belong to a social club that engages in invidious discrimination." During the hearing, Kennedy had stated that he believed it would have been better for Brown to resign from the all-white club. Thurmond stated afterward that he understood the judge's feeling that a resignation would have been verification of his thirty-three years with the club being improper.[182] On October 10, President Carter signed the Federal Magistrate Act of 1979, an expansion of the jurisdiction of American magistrates in regards to civil and criminal cases. Carter noted Thurmond as one of the members of Congress who had shown leadership on the measure, without whose efforts it would have never passed.[183] Senate sources reported in October that Ted Kennedy had asked Majority Leader Robert Byrd to bring the Illinois Brick bill to the floor, the controversial antitrust measure attracting the opposition of Thurmond, who joined Orrin Hatch in threatening a filibuster of the bill.[184] In their stance against the bill, Thurmond and Hatch argued the bill's enactment would result in businesses being exposed to endless litigation as well as the possibility of duplicative awards of damages to direct and indirect purchasers.[185]

Foreign policy

In August 1970, the Senate voted against authorizing the United States to pay larger allowances to Vietnamese-based allied troops than those paid to American soldiers; Thurmond was the only senator to deliver remarks against the proposal.[186] In September, during remarks to the World Anti Communist League, Thurmond called on Japan to increase defensive efforts and exercise leadership in that strategy with respect to non‐Communist Asia. Thurmond requested that Japan exercise restraints in textile exports to the United States and stated that he was in favor of trade between the US and Japan with the exception of instances of it closing American textile mills or when it caused textile workers to lose their jobs. He furthered that the United States intended to hold on to its prior commitments and that an address by President Nixon the previous year in which Nixon called for allies of Asia to play a larger role in their defense demonstrated American trust "in the capacities and growth of our allies." Thurmond also defended the Vietnam policy of the Nixon administration, saying that the president was making the best of the situation that he had inherited from Kennedy and Johnson while admitting that he personally favored a total victory in the war.[187]

On April 11, 1971, Thurmond called for the exoneration of William Calley following his conviction of participating in the My Lai Massacre, stating that the "victims at Mylai were casualties to the brutality of war" and Calley had acted off of order.[188] Calley's petition for habeas corpus was granted three years later, in addition to his immediate release from house arrest.[189] In June 1971, during a speech, Thurmond advocated against lifting the trade embargo with China, stating that its communist regime had engaged in a propaganda effort to weaken State Department support for the embargo and that Americans would remember the decision with harshness.[190] Two days later, President Nixon ordered trade with China be permitted, ending the embargo.[191][192]

In April 1972, Thurmond was the only Republican senator on the Senate Armed Services Committee to oppose terminating the United States Army's controversial Cheyenne helicopter project while it reduced $450 million from the weapons program of the Pentagon.[160]

By early 1973, Thurmond expressed the view that American aid to the rebuilding of South Vietnam should be hinged on the amount of support it was receiving from China and the Soviet Union.[193]

In 1974,[194] Thurmond and Democrat John L. McClellan wrote a resolution to continue American sovereignty by the Panama Canal and zone. Thurmond stated that the rhetoric delivered by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger suggested that the "Canal Zone is already Panamanian territory and the only question involved is the transfer of jurisdiction."[195] In June 1974, Senator Henry M. Jackson informed Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee that he had arranged for Thurmond to cosponsor an amendment revising the present export control system and restricting trade with the Soviet Union while granting the Defense Secretary power to veto any export that might "significantly increase the military capability" of either the Soviet Union or other Communist countries. Jackson introduced the amendment after Howard M. Metzenbaum yielded the Senate floor before Majority Leader Mike Mansfield caught on to the proposal and succeeded in preventing an immediate vote.[196]

In January 1975, Thurmond and William Scott toured South Vietnam, Thurmond receiving a medal from President of South Vietnam Nguyễn Văn Thiệu. The award was seen as part of an attempt by South Vietnam to court American congressional votes in its favor.[197] In March, Thurmond and John McClellan assembled a group of thirty-five senators to sponsor a resolution in opposition to the Panama Canal Treaty's ending United States sovereignty over the Panama Canal Zone. Though the thirty-seven votes of the senators were enough to override a treaty negotiated by the Ford administration, an official said that the Thurmond-McClellan resolution was not a concern.[198] In June, as the Senate weighed a reduction in a $25 billion weapons procurement measure and to delete research funds to improve the accuracy and power of intercontinental ballistic missiles and warheads, Thurmond and Harry F. Byrd Jr. warned that the Soviet Union was attempting an increase on its missile accuracy and advocated for the United States to follow suit with its own missiles.[199] Later that month, Thurmond and Jesse Helms wrote to President Ford requesting he meet with Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn ahead of a speech on June 30 during an AFL–CIO dinner. The White House responded to Thurmond and Helms with an insistence that President Ford was too busy to meet with Solzhenitsyn, while later White House sources indicated that Ford had declined the meeting at the counsel of his advisors.[200]

The period of late 1977 marked the beginning of an organized effort by conservatives to display opposition to the ratification of the Panama Canal treaty by the Senate, which included a scheduled televised appearance by Thurmond.[201] Thurmond advocated for forging a new relationship with Panama and against the U.S. giving up sovereignty in the canal zone, in addition to casting doubts on Panama's ability to govern alone: "There is no way that a Panarnaniain government could be objective about the administration of an enterprise so large in comparison to the rest of the national enterprise, public and private."[202] In late August 1977, the New York Times wrote "President Carter can be grateful that the opposition to his compromise Panama treaty is now being led by Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina and Senator Jesse Helms of North Carolina."[203] Speaking on the Panama Canal neutrality treaty, Thurmond said it was "the big giveaway of the century."[204][205] The treaty was ratified by the Senate on March 16, 1978.[206]

In December 1979, Thurmond was one of ten senators on the Senate Armed Services Committee to sign a report urging President Carter to delay the vote on proposed treaty with between the US and Soviet Union to limit nuclear arms.[207]

Nixon resignation

In July 1973, Thurmond was one of ten Republican senators in a group headed by Carl T. Curtis invited to the White House to reaffirm their support for President Nixon in light of recent scandals and criticism of the president within his own party.[208] In October, President Nixon ordered the firing of independent special prosecutor Archibald Cox in an event that saw the resignations of Attorney General Elliot Richardson and Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus before Robert Bork fulfilled the president's order. The day after the firing, Democrat Birch Bayh charged Thurmond with "browbeating" Cox during Senate Judiciary Committee hearings on the firing. Thurmond replied that Bayh was "below a snake" in the event that he had intended to impugn his motives. Thurmond was noted for joining Edward J. Gurney in questioning Cox "at length in an attempt to show that he was biased against" Nixon and his administration. Thurmond asked Cox if eleven members of his staff had worked for Presidents Kennedy and Johnson and was interrupted multiple times by James Eastland to allow for Cox to fully answer questions.[209]

In May 1974, the House Judiciary Committee opened impeachment hearings against President Nixon after the release of 1,200 pages of transcripts of White House conversations between him and his aides and the administration became engulfed in the scandal that would come to be known as Watergate. Thurmond, along with William L. Scott and James B. Allen agreed with Senator Carl T. Curtis on the equation of resignation with mob rule and the group declined defending Nixon's conduct. Thurmond opined that Nixon was "the only President we have" and questioned why Congress would want to weaken his hand in negotiating with other countries.[210] In August, Newsweek published a list by the White House including Thurmond as one of thirty-six senators that the administration believed would support President Nixon in the event of his impeachment and being brought to trial by the Senate. The article stated that some supporters were not fully convinced and this would further peril the administration as 34 needed to prevent conviction.[211] Nixon resigned on August 9 in light of near-certain impeachment.[212]

Carter nominees

In July 1979, as the Senate weighed voting on the nomination of Assistant Attorney General Patricia M. Wald to the United States Court of Appeals in Washington, Thurmond joined Paul Laxalt and Alan Simpson recorded their opposition.[213] Later that month, Thurmond asked Attorney General nominee Benjamin R. Civiletti if President Carter had made him give a pledge of loyalty or an assurance of complete independence.[214] In September, the Senate Judiciary Committee approved 30 of President Carter's nominees, the closest vote being waged against Abner J. Mikva, who the president had nominated for the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. Thurmond was one of the five Republicans to vote against Mikva.[215] In November, President Carter nominated José A. Cabranes to fill a vacancy on the United States District Court for the District of Connecticut. Thurmond submitted a series of written questions to Cabranes, whose answers were credited with clarifying his views on issues.[216] Cabranes was confirmed for the position.

1978 re-election campaign

In his general election campaign, Thurmond faced Charles Ravenel, a local banker and former gubernatorial candidate.[217] Ravenel charged Thurmond with not standing up for South Carolina's educational needs and having been behind the lack of funding. Thurmond responded to the charges by stating that he thought the state had made advancements in its education system.[218] Thurmond and Ravenel made a joint appearance in April, where Thurmond discussed his position on a variety of issues.[219]

The higher amount of African-Americans voting in elections was taken into account by the Ravenel campaign, which sought to gain this group of voters by reviving interest in older statements by Thurmond. In his courting of black voters, Thurmond was noted to have not undergone "any ideological transformation" but instead devoted himself to making personal contact with members of the minority group. Thurmond's influence in national politics allowed him to have correspondence with staffers from the Nixon administration which gave him "a unique advantage in announcing federal grants and bird-dogging federal projects of particular interest to black voters."[220]

By May 1978, Thurmond held a 30-point lead over Ravenel among double digits of undecided voters.[221] Thurmond won a fifth term with 351,733 votes to Ravenel's 281,119. The race would later be assessed as the last serious challenge to Thurmond during his career.[222]

1980 presidential election

Thurmond endorsed the presidential candidacy of John Connally,[223] on December 27, 1979.[224] The Republican election cycle that year also featured Reagan,[225] Thurmond explaining that he had chosen to back Connally this time around because of the latter's wide government experience which he believed would benefit the U.S. in both domestic and foreign matters.[226] Thurmond stated that the Iran hostage crisis would have never happened were Connally the sitting president as Iranians were familiar with his strength. The Washington Post noted Thurmond seeming "to cast himself for a role of regional leadership in the Connally campaign similar to the one he played in 1968" for the Nixon campaign.[227] Connally subsequently was defeated in the South Carolina primary by Reagan, thanking Thurmond and his wife for doing more to support his campaign in the state than anyone else.[228] In August 1980, Thurmond gave a "tense cross examination" of Billy Carter, the brother of President Carter who had come under scrutiny for his relationship with Libya and receiving funds from the country. The Billy Carter controversy also was favored by Democrats wishing to replace Carter as the party's nominee in the general election.[229] Thurmond questioned Carter over his prior refusal to disclose the amount of funds he had received from public appearances following the 1976 election of his brother as president,[230] and stated his skepticism with some of the points made.[231]

During a November 6, 1980 press conference, days after the 1980 Senate election, in which the Republicans unexpectedly won a majority,[232] Thurmond pledged that he would seek a death penalty law.[233] During an interview the following year, Thurmond said, "I am convinced the death penalty is a deterrent to crime. I had to sentence four people to the electric chair. I did not make the decision; the jury made it. It was my duty to pass sentence, because the jury had found them guilty and did not recommend mercy. But if I had been on the jury, I would have arrived at the same decision; in all four of those cases."[234] After the presidential election, Thurmond and Helms sponsored a Senate amendment to a Department of Justice appropriations bill denying the department the power to participate in busing, due to objections over federal involvement, but, although passed by Congress, was vetoed by a lame duck Carter.[235][236] In December 1980, Thurmond met with President-elect Reagan and recommended former South Carolina governor James B. Edwards for United States Secretary of Energy in the incoming administration.[237] Reagan later named Edwards Energy Secretary, and the latter served in that position for over a year.[238][239] In early January 1981, the Justice Department revealed it was carrying out a suit against Charleston County for school officials declining to propose a desegregation method for its public schools. Thurmond responded by noting that South Carolina did not support President Carter in the general election and stating that this may have contributed to the Justice Department's decision.[240] On January 11, Thurmond stated that he would ask the incoming Reagan administration to look into the facts of the case before proceeding.[241]

Post-1970 views regarding race

In 1970, black people still constituted some 30 percent of South Carolina's population; in 1900, they had constituted 58.4 percent of the state's population.[242] Thousands of black people left the state during the first half of the 20th century in the Great Migration to escape the Jim Crow laws and seek opportunities in the industrial cities of the North and Midwest. After the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was implemented, African Americans were legally protected in exercising their constitutional rights as United States citizens to register to vote in South Carolina without harassment or discrimination. State politicians could no longer ignore this voting bloc, who were allied with increasing numbers of white residents who supported civil rights.

Thurmond appointed Thomas Moss, an African American, to his Senate staff in 1971. It has been described as the first such appointment by a member of the South Carolina congressional delegation (it was incorrectly reported by many sources as the first senatorial appointment of an African American, but Mississippi Senator Pat Harrison had hired clerk-librarian Jesse Nichols in 1937). In 1983, he supported legislation to make the birthday of Martin Luther King Jr. a federal holiday.[6] In South Carolina, the honor was diluted; until 2000 the state offered employees the option to celebrate this holiday or substitute one of three Confederate holidays instead. Despite this, Thurmond never explicitly renounced his earlier views on racial segregation.[7][8][243][244]

1980s

Thurmond became President pro tempore of the U.S. Senate in 1981, and was part of the U.S. delegation to the funeral of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, Thurmond being accompanied by Sadat's pen pal Sam Brown.[245]

In January 1982, Thurmond and Vice President George H. W. Bush were met with protestors while Thurmond was being inducted into the South Carolina Hall of Fame, the protestors holding signs charging Thurmond with racism and attacking the Voting Rights Act.[246]

In the 1984 presidential election, Thurmond was cited along with Carroll Campbell and South Carolina Republican Party Director Warren Tompkins by Republicans as the forces binding the Reagan-Bush ticket to South Carolina's electoral votes.[247] Thurmond attended President Reagan's October 15 re-election campaign speech in the Allied Health Building on the Greenville Technical College campus in Greenville, South Carolina.[248]

Thurmond attended the September 7, 1985 dedication of the Richard B. Russell Dam, praising the dam with having met "the ever increasing needs of the Southeast."[249]

In June 1986, Thurmond sent a letter to Attorney General Edwin Meese requesting "an inquiry into the activities of former Commerce Department official Walter Lenahan, and expressed concern about an alleged leak of U.S. trade information to textile-exporting nations."[250]

In January 1987, Thurmond swore in Carroll A. Campbell Jr. as the 112th Governor of South Carolina.[251]

On February 23, 1988, Thurmond endorsed fellow senator Bob Dole in the Republican presidential primary, acknowledging his previous intent to remain neutral during the nominating process.[252] The Thurmond endorsement served to change the Dole campaign's initial plans of skipping the South Carolina primary, where Vice President Bush defeated Dole. The Bush campaign subsequently won other Southern states and the nomination, leading Michael Oreskes to reflect that Dole "was hurt by an endorsement that led him astray."[253]

In August 1988, as the Senate voted on the nomination of Dick Thornburgh as U.S. Attorney General, Thurmond stated that Thornburgh had the qualities necessary for an Attorney General to possess, citing his "integrity, honesty, professionalism and independence." Thornburgh was confirmed, and served for the remainder of the Reagan administration as well as the Bush administration.[254]

Following the 1988 Presidential election, George H. W. Bush nominated John Tower for United States Secretary of Defense. After Tower's nomination was rejected by the Senate, Thurmond asked, "What does it say when the leader of the free world can't get a Cabinet member confirmed?"[255]

In August 1989, the Senate Judiciary Committee voted evenly on the nomination of William C. Lucas for Assist Attorney General for Civil Rights, terminating the nomination that required a majority to proceed to the entirety of the chamber. Among his support, Thurmond noted that Lucas was a minority, and reflected on their lack of opportunities in years prior, adding, "I know down South they didn't and up North either. We had de jure segregation and up North you had de facto segregation. There was segregation in both places, and black people didn't have the chance in either place that they should have had. Now's the chance to give them a chance." Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee Joe Biden refuted Thurmond's argument by mentioning that Senate critics of Lucas were civil rights supporters who had a problem with his lack of qualifications.[256]

In September 1989, Hurricane Hugo hit the Southeast United States, causing twenty-seven deaths in South Carolina. In response, Congress approved a $1.1 billion emergency aid package for victims of the hurricane in what was the largest disaster relief package in American history. Before the vote, Thurmond said of the hurricane, "I have never seen so much damage in my life. It looked like there had been a war there. We need all the help we can get."[257] Thurmond accompanied President Bush aboard Air Force One when he visited the state at the end of the month, and revealed that Bush had written a check of $1,000 to South Carolina Red Cross as a showing of personal support for those effected.[258]

Domestic policy

In 1980, Thurmond and Democratic Representative John Conyers jointly sponsored a constitutional amendment to change the tenure of the President to a single six-year term.[259][260]