Brooks County, Georgia

Brooks County is a county located in the U.S. state of Georgia, on its southern border with Florida. As of the 2010 census, the population was 16,243.[1] The county seat is Quitman.[2] The county was created in 1858 from portions of Lowndes and Thomas counties by an act of the Georgia General Assembly and was named for pro-slavery U.S. Representative Preston Brooks after he severely beat abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner with a cane for delivering a speech that upset him.

Brooks County | |

|---|---|

Brooks County Courthouse in Quitman | |

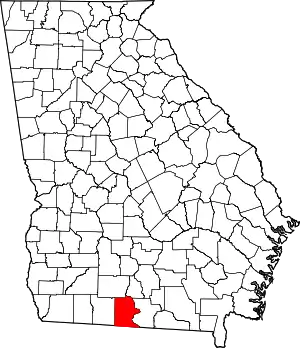

Location within the U.S. state of Georgia | |

Georgia's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 30°43′44″N 83°42′54″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | December 11, 1858 |

| Named for | Preston Brooks |

| Seat | Quitman |

| Largest city | Quitman |

| Area | |

| • Total | 498 sq mi (1,290 km2) |

| • Land | 493 sq mi (1,280 km2) |

| • Water | 4.8 sq mi (12 km2) 1.0%% |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2019) | 15,457 |

| • Density | 33/sq mi (13/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 8th |

| Website | www |

Brooks County is included in the Valdosta, GA Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

Native Americans and the Spanish

Historic Native peoples occupying the area at the time of European encounter were the Apalachee and the Lower Creek.[3] The first Europeans in what is now Brooks County were Spanish missionaries from their colony in Florida, who arrived around 1570.

Early history

The area that was to become Brooks County was first opened up to European-American settlement in 1818 when Irwin County was established. Coffee Road was built through the region in the 1820s. Lowndes County's first court session was held at the tavern owned ran by Sion Hall on the Coffee Road, near what is now Morven, Georgia in Brooks County.

Establishment

Many residents of Lowndes County were unhappy when the Atlantic and Gulf Railroad announced June 17, 1858 that they had selected a planned route that would bypass Troupville, the county seat. On June 22 at 3:00 am, the Lowndes County courthouse at Troupville was set aflame by William B. Crawford, who fled to South Carolina after being released on bond.

On August 9, a meeting convened in the academy building in Troupville, at which residents decided to divide Lowndes and create a new county to the west of the Withlacoochee River, to be called Brooks County.

On December 11, 1858, Brooks County was officially organized by the state legislature from parts of Lowndes and Thomas counties. It was named for Preston Brooks, a member of Congress prior to the Civil War. He was best known for his vicious physical assault in Congress of the older Senator Charles Sumner, an anti-slavery advocate from Massachusetts.

The county had been developed along the waterways for cotton plantations, dependent on enslaved laborers, many of whom were transported to the South in the domestic slave trade during the antebellum years. Cotton brought a high return from local and international markets, making large planters wealthy. At the time of the 1860 federal census, Brooks County had a white population of 3,067, a Free people of color population of 2, and a slave population of 3,282. The Atlantic and Gulf Railroad reached Quitman, the county seat, on October 23, 1860.

Civil War

During the Civil War, the county was the main producer of food for the Confederacy; it became known as the "Smokehouse of the Confederacy."[4]

Some Confederate Army regiments were raised from the men of Brooks County. Plantation owners, county officials, and slave patrol members were exempt from military conscription, which caused some contention between the different economic classes in Brooks County.

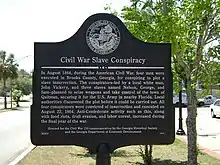

In August 1864, a local white man named John Vickery began plotting a slave rebellion. His plan called for killing the slave owners, stealing what weapons they could find, setting fire to Quitman, going to Madison, Florida, burning the town, getting help from Union troops from the Gulf Coast, and then returning to Quitman. On the evening before the rebellion, a slave was arrested for theft and interrogated. Vickery was soon arrested as well. Vickery and four slave suspects were given a military trial by the local militia. Two Confederate deserters from Florida were also believed to have been involved, but were not caught by the time of the trial.[5]

On August 23, 1864 at 6:00 p.m., Vickery, and slaves Sam, Nelson, and George were publicly hanged in Quitman. The court could not reach a decision on the guilt of Warren, a slave held by Buford Elliot.[5]

Post-Reconstruction and imposition of Jim Crow

After the war, many freedmen worked as sharecroppers or tenant farmers, in an effort to preserve some independence from planters. Following the war and the Reconstruction era, Brooks County was one of the areas with a high rate of racial violence by whites against blacks. Its 20 deaths make it the county in Georgia that had the third-highest number of lynchings from 1870 to 1950.[6] (From 1880 to 1930, Georgia had the highest number of such extrajudicial murders in the country).[7] See, for example, the Brooks County race war of 1894.

In May 1918, at least 13 African Americans were killed during a white manhunt and rampage after Sidney Johnson killed an abusive white planter.[8] Johnson had been forced to work for the man under the state's abusive convict lease system. Among those killed were Hayes Turner, and the next day his wife Mary Turner, who was eight months pregnant. They were the parents of two children. Mary Turner had condemned the mob's killing of her husband. She was abducted by the mob in Brooks County and brutally murdered at Folsom's Bridge on the Little River on the Lowndes County side; her unborn child was cut from her body and killed separately. During the next two weeks, at least another eleven blacks were killed by the mob. Johnson was killed in a shootout with police. As many as 500 African Americans fled Lowndes and Brooks counties to escape future violence.[9]

Mary Turner's lynching drew widespread condemnation nationally. It was a catalyst for the Anti-Lynching Crusaders campaign for the 1922 Dyer Bill, sponsored by Leonidas Dyer of St. Louis. It proposed to make lynching a federal crime, as southern states essentially never prosecuted the crimes.[10] The Solid South Democratic block of white senators consistently defeated such legislation, aided by having disenfranchised most black voters in the South. In 2010, a state historical marker, encaptioned "Mary Turner and the Lynching Rampage," was installed at Folsom's Bridge in Lowndes County to commemorate these atrocities.

Modern

In the 21st century, Brooks County is classified as being in the Plantation Trace tourist region.

Historical sites

- Brooks County Courthouse- The Brooks County Courthouse was constructed in 1864 in the county seat of Quitman, Georgia. It was designed by architect John Wind. Brooks County officials paid for the structure with $14,958 in Confederate money. The currency soon became useless.

- Brooks County Museum and Cultural Center - The former library, this building was adapted for use as a cultural center. It is the site of a series of music, art, and culinary events throughout the year.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 498 square miles (1,290 km2), of which 493 square miles (1,280 km2) is land and 4.8 square miles (12 km2) (1.0%) is water.[11]

The eastern boundary of the county is made up of the Little River (Withlacoochee River) and the Withlacoochee River, which together meander along a distance of over 100 miles (160 km) to form that boundary. These river boundaries are shared with Cook and Lowndes counties. The southern boundary of the county has a mutual east–west interface of about 25 miles (40 km) with Florida, although it is not continuous. The county is discontinuous along the Florida border, with the easternmost section about a mile east of the rest of the county. This section presently consists of one parcel, recorded as 350 acres (1.4 km2), although it has a border with Florida of almost 2 miles (3.2 km). The county shares a north–south boundary about 26 miles (42 km) in length with Thomas County to the west. It also shares an east–west boundary of 10 miles (16 km) and a north–south boundary of 3 miles (4.8 km) with Colquitt County to the northwest. The county has over 10,000 parcels of land, with 19 over 2,000 acres (8.1 km2) and two more than 5,000 acres (20 km2).

The county is home to several endangered plant and animal species, including the Pond Spicebush, the Wood Stork, and the Eastern Indigo snake.

The majority of Brooks County, including the northwestern portion, all of central Brooks County, and the southeastern corner, is located in the Withlacoochee River sub-basin of the Suwannee River basin. Most of the southern edge of the county is located in the Aucilla River sub-basin of the larger Aucilla-Waccasassa basin. The county's northeastern portion, centered on Morven and including Barney, is located in the Little River sub-basin of the same Suwannee River basin.[12]

Adjacent counties

- Cook County - northeast (created 1918 from Berrien County)

- Lowndes County - east (created 1825 from Irwin County)

- Madison County, Florida - southeast

- Jefferson County, Florida - southwest

- Thomas County - west (created 1825 from Early and Decatur counties)

- Colquitt County - northwest (created in 1856 from Thomas and Lowndes counties)

Transportation

Major highways

GA Bike Route 10

Georgia State Bicycle Route 10 is one of 14 bike routes across Georgia. Route 10 is 246 miles (396 km) long and goes from Lake Seminole in the west to Jekyll Island in the east. It runs a west–east route, of approximately 27.3 miles (43.9 km), through the county and passes through downtown Quitman.

Airport

BROOKS CO (4J5) Runway length 5000' Lights, CTAF 122.9 FSS Macon 122.4 [14]

Demographics

As a result of the demand for slave labor to work the cotton plantations, the county was majority black from before the Civil War well into the 20th century. Starting in the early 1900s, hundreds of blacks left the county in the Great Migration to northern and midwestern industrial cities to gain better opportunities and escape the oppressive Jim Crow conditions, including the highest rate of lynchings of blacks in Georgia from 1880 to 1930.[7]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 6,356 | — | |

| 1870 | 8,342 | 31.2% | |

| 1880 | 11,727 | 40.6% | |

| 1890 | 13,979 | 19.2% | |

| 1900 | 18,606 | 33.1% | |

| 1910 | 23,832 | 28.1% | |

| 1920 | 24,538 | 3.0% | |

| 1930 | 21,330 | −13.1% | |

| 1940 | 20,497 | −3.9% | |

| 1950 | 18,169 | −11.4% | |

| 1960 | 15,292 | −15.8% | |

| 1970 | 13,739 | −10.2% | |

| 1980 | 15,255 | 11.0% | |

| 1990 | 15,398 | 0.9% | |

| 2000 | 16,450 | 6.8% | |

| 2010 | 16,243 | −1.3% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 15,457 | [15] | −4.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[16] 1790-1960[17] 1900-1990[18] 1990-2000[19] 2010-2019[1] | |||

2000 census

As of the census[20] of 2000, there were 16,450 people, 6,155 households, and 4,370 families residing in the county. The population density was 33 people per square mile (13/km2). There were 7,118 housing units at an average density of 14 per square mile (6/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 57.36% Caucasian, 39.34% Black or African American, 0.30% Native American, 0.26% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 1.76% from other races, and 0.94% from two or more races. 3.07% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 6,155 households, out of which 31.60% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 48.30% were married couples living together, 18.10% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.00% were non-families. 25.20% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.00% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.61 and the average family size was 3.11.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 26.90% under the age of 18, 8.90% from 18 to 24, 26.90% from 25 to 44, 22.30% from 45 to 64, and 15.00% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females there were 92.20 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.80 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $26,911, and the median income for a family was $32,382. Males had a median income of $26,303 versus $18,925 for females. The per capita income for the county was $13,977. About 19.10% of families and 23.40% of the population were below the poverty line, including 32.40% of those under age 18 and 20.10% of those age 65 or over.

2010 census

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 16,243 people, 6,457 households, and 4,379 families residing in the county.[21] The population density was 32.9 inhabitants per square mile (12.7/km2). There were 7,706 housing units at an average density of 15.6 per square mile (6.0/km2).[22] The racial makeup of the county was 59.9% white, 35.3% black or African American, 0.3% Asian, 0.3% American Indian, 0.1% Pacific islander, 2.9% from other races, and 1.2% from two or more races. Those of Hispanic or Latino origin made up 5.3% of the population.[21] In terms of ancestry, 16.3% were American, 8.3% were Irish, 6.4% were English, and 5.9% were German.[23]

Of the 6,457 households, 31.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.2% were married couples living together, 16.8% had a female householder with no husband present, 32.2% were non-families, and 27.6% of all households were made up of individuals. The average household size was 2.52 and the average family size was 3.06. The median age was 40.3 years.[21]

The median income for a household in the county was $41,309 and the median income for a family was $47,599. Males had a median income of $38,791 versus $25,006 for females. The per capita income for the county was $20,346. About 14.7% of families and 17.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 21.5% of those under age 18 and 22.3% of those age 65 or over.[24]

Education

The Brooks County School District offers pre-school to grade twelve. There are two elementary schools, a middle school and a high school, Brooks County High School.[25] The district has 167 full-time teachers and over 2,563 students.[26]

- North Brooks Elementary School

- Quitman Elementary School

- Brooks County Middle School

- Brooks County High School

The county is serviced by the Brooks County Public Library.

Government

The Government consists of a five-member Board of Commissioners. Under the guidelines of the Commissioners is a County Administrator, a Sheriff and Tax Commissioner, the Judicial System and other Boards and Authorities.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 60.0% 4,260 | 39.3% 2,790 | 0.7% 50 |

| 2016 | 58.4% 3,701 | 39.9% 2,528 | 1.7% 107 |

| 2012 | 52.6% 3,554 | 46.5% 3,138 | 0.9% 62 |

| 2008 | 56.5% 3,507 | 43.0% 2,669 | 0.5% 29 |

| 2004 | 56.9% 2,912 | 42.9% 2,193 | 0.2% 12 |

| 2000 | 52.9% 2,406 | 46.1% 2,096 | 1.1% 49 |

| 1996 | 42.9% 1,738 | 48.8% 1,977 | 8.4% 339 |

| 1992 | 41.2% 1,779 | 43.9% 1,895 | 14.9% 641 |

| 1988 | 58.5% 2,136 | 41.1% 1,500 | 0.4% 13 |

| 1984 | 57.3% 2,229 | 42.7% 1,661 | |

| 1980 | 40.4% 1,546 | 58.3% 2,230 | 1.3% 51 |

| 1976 | 29.4% 1,102 | 70.7% 2,653 | |

| 1972 | 79.1% 2,430 | 20.9% 643 | |

| 1968 | 15.6% 589 | 20.8% 787 | 63.6% 2,404 |

| 1964 | 69.5% 2,342 | 30.5% 1,027 | 0.0% 1 |

| 1960 | 33.8% 765 | 66.2% 1,500 | |

| 1956 | 21.6% 534 | 78.4% 1,936 | |

| 1952 | 30.0% 800 | 70.0% 1,866 | |

| 1948 | 11.2% 188 | 58.1% 975 | 30.6% 514 |

| 1944 | 16.8% 279 | 83.2% 1,381 | |

| 1940 | 16.0% 248 | 83.9% 1,300 | 0.1% 1 |

| 1936 | 6.8% 94 | 92.7% 1,277 | 0.4% 6 |

| 1932 | 5.0% 75 | 94.7% 1,426 | 0.3% 5 |

| 1928 | 20.0% 192 | 80.0% 770 | |

| 1924 | 9.7% 128 | 89.3% 1,179 | 1.1% 14 |

| 1920 | 11.3% 76 | 88.7% 597 | |

| 1916 | 2.3% 25 | 88.3% 969 | 9.4% 103 |

| 1912 | 5.4% 42 | 89.8% 695 | 4.8% 37 |

Recreation

Brooks County is well known for its wildlife. Quail, dove, ducks, and deer abound in the fields and forests. Brooks County also offers excellent fishing in its many lakes and streams, which are open to the public.

Hospital

Brooks County Hospital, a part of Archbold Medical Center, a 25-bed facility[28] was established in 1935 and has 24-hour emergency facilities.

Communities

Cities

- Barwick (partly in Thomas County, Georgia)

- Morven

- Pavo (partly in Thomas County, Georgia)

- Quitman

Unincorporated communities

- Barney

- Dixie

- Grooverville

- New Rock Hill

- Pidcock

References

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Huxford, Folks (1978). The History of Brooks County 1858-1948. p. 10.

- History of Brooks County Georgia 1858-1948

- Williams, David; Williams, Teresa Crisp; Carlson, David (2002). Plain Folk in a Rich Man's War: Class and Dissent in Confederate Georgia. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida Press. pp. 144–150. ISBN 978-0813028361.

- Lynching in America/ Supplement: Lynchings by County, 3rd Edition, 2015, p. 3

- Meyers, Christopher C (2006). ""Killing Them by the Wholesale": A Lynching Rampage in South Georgia". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. JSTOR. 90 (2): 214–235. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- Gullberg, Greg (May 22, 2012). "South Georgia Citizens Fight To Keep Mary Turner's Story Alive". WCTV.

- "Remembering Mary Turner". The Mary Turner Project. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- Armstrong, Julie. "Mary Turner and the Memory of Lynching". University of Georgia Press. Archived from the original on April 15, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "Georgia Soil and Water Conservation Commission Interactive Mapping Experience". Georgia Soil and Water Conservation Commission. Retrieved November 27, 2015.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2011. Retrieved February 17, 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "4J5 - Quitman Brooks County Airport". AirNav. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- "DP-1 Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- "Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 - County". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- "DP02 SELECTED SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS IN THE UNITED STATES – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- "DP03 SELECTED ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- Georgia Board of Education, Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- School Stats, Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- "Brooks County Hospital (Quitman, GA) Detailed Hospital Profile". Hospital-data.com. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

External links

- Brooks County Board of Tax Assessors

- Brooks County Public Library

- Brooks County Criminal Court

- Brooks County historical marker

- Columbia Primitive Baptist Church historical marker