Colliers, West Virginia

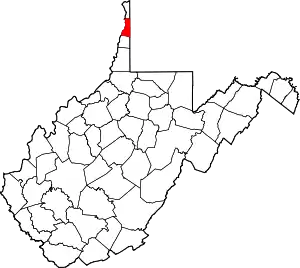

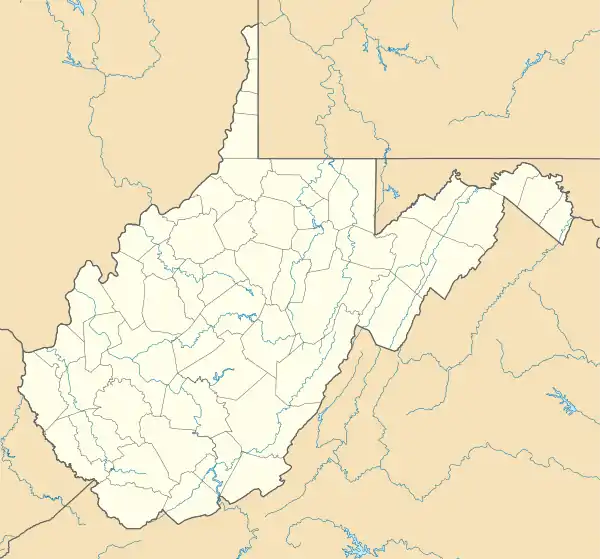

Colliers is an unincorporated community in Brooke County, West Virginia. It is the second oldest town in Brooke County, Wellsburg being the oldest. Its population expanded steadily throughout the 1800s and into the 1900s because a section of the Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Chicago, and St. Louis (PCC&StL) Railroad ran through the town, and because numerous coal mines were established, including the Blanch Coal Mine[2] and the Locust Grove Mine.[3] After both enterprises closed, the population declined until Colliers became a small, residential community. Throughout its existence, Colliers’ social life has revolved primarily around the local schools and churches.[4]

Colliers | |

|---|---|

Colliers Location within the state of West Virginia  Colliers Colliers (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 40°22′1″N 80°32′28″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | West Virginia |

| County | Brooke |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 26035 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1537521[1] |

Demographic Information

Colliers has a population of 2,045 people. Of these, 2,008 of the people are Caucasian, eight are African American, eight are Asian/Pacific Islanders, fourteen are Hispanic, one is American Indian/Eskimo/Aleut, and nineteen are listed as other. 1,085 people are male, and 959 are female.[5]

History

In 1771, Jacob Collier founded the settlement of Colliers. There was a small fort located in this settlement. The fort was used during battles with Native Americans during the late 1700s.[6]

The city of Colliers was officially founded in 1843. Many workers and their families immigrated from outside the United States. The coal mining industry was profitable, and numerous people immigrated to Colliers to work in the mines. These immigrants formed a community on the west end of Colliers called Logrow, or the Boardwalk. The PCC&StL Railroad ran through this section of Colliers, which brought about the rise of a pool hall, a movie theater, and a mining company store, among other establishments.[7]

The east end of Colliers was known as Mine Hill.[4] The train also stopped here, and as a result, Mine Hill saw the appearance of a restaurant, a boarding house, barbershops, and general stores.[7]

However, in the 1920s, the mines began running out of minerals and were shut down. Colliers’ population decreased, especially in Logrow. The Great Depression hit the town hard, and many businesses closed. After the Depression, Colliers did not fully return to its former prosperity, as the mines could not reopen.[7] The main source of income for the town became the Colliers Steel Corporation.[4] After the corporation closed, the steel industry was revived by the 1998 opening of the Mountaineer Metal Products company.[8]

Schools

In the mid-1800s, Elisha Stansbury, a man who owned 335 acres of land in Colliers and the surrounding area, realized that the town needed a school to educate the children, including his own eight. He donated a portion of his land on the west end of Colliers for a school. The school, known as the Number 2 School, was made up of one 60’x30’ room. The typical school year lasted between four and six months to ensure that the children would be free to assist their parents during harvests, as well as to avoid the harsh conditions of winter.[7]

In the eastern section of Colliers, Elijah Robinson donated land for another school to be built. This school was known as the Number 13 School. It was built in 1879, when the average school year lasted around seven months.[7]

Both the Number 2 and Number 13 Schools lasted until 1907, when they were consolidated into a new school building located nearer to the center of town. This school was known as the First Colliers School. It had four classrooms, which was more than Colliers’ previous schools. The First Colliers School lasted until 1921.[7]

During this time, African American children were not allowed to attend the same schools as white children. There were several immigrants and African Americans living in the Logrow community, and their children could not attend school. A spare room above the pool hall became a temporary classroom until a more suitable building could be acquired.[7]

In 1907, the students of the Number 2 School were transferred to the more modern First Colliers School. With the building empty, the African American students were free to use it for their own education. The school continued to educate the African American and immigrant population until the mid-1930s, when it closed.[7]

In 1939, the students who attended the Number 2 School were bussed to the new Ferry Glen School. This school did not remain open for long; it closed in 1946 due to a lack of attendance.[7]

Following the closure of the First Colliers School in 1921, the Second Colliers School opened. This school was a two-story red brick building. There were four classrooms on each floor, as well as restrooms, offices, an auditorium, and a cafeteria. In 1953, the school was remodeled to add two new classrooms, a restroom, and cafeteria equipment, and to improve the plumbing, heating, and electrical systems of the building. The building was further improved in the 1960s, adding fireproof doors at the top of the stairs, new desks, a gas boiler, and floor tiling in the classrooms.[7]

In 1985, the Second Colliers School was replaced by the Colliers Primary School, which closed after the 2017-2018 school year. This school was a one-story building constructed of brown brick. It had the capacity to hold 250 children, but in 1995, the enrollment was 165.[7] Enrollment has marginally increased to 175 in 2013.[9]

Colliers Primary School was ranked 94th out of 420 primary schools in the state of West Virginia for the year 2017, with an overall grade of a B from Niche.[10] Colliers Primary School was named a 2017 National Blue Ribbon School with the designation as an Exemplary High Performing School. Colliers Primary was the first school in Brooke County to be nominated by the West Virginia Department of Education as a National Blue Ribbon School.[11] Also, the Colliers Primary School principal, JoEllen Connolly, was presented the national Terrel H. Bell Outstanding Leadership Award by the U.S. Department of Education. The award was a first for any West Virginia administrator.[12]

Churches

There are several churches in Colliers. The earliest church is the Colliers United Methodist Church, which was organized in 1834. In 1898, the Colliers Christian Church was founded as a non-denominational church. The First Nazarene Church of Colliers opened in 1958.[4] The latest church to open is Open Door Baptist Church, which was first organized in 1982 and officially constituted in 1985.[13]

Mines

Blanch Mine

Blanch Mine was a coal mine owned by L.C. Smith, William Smith, and John McNulty. It was plagued by tragic accidents in the late 1800s. On November 21, 1892, three workers, one of them only fifteen years old, were killed and seven were wounded when twenty-five kegs of powder exploded inside the mine. Luckily, most of the workers had exited the mine to eat by the time the accident occurred.[14]

Two years later, on November 20, 1894, another explosion was caused in the mine by a new miner detonating an overcharged blast. The accident caused the deaths of seven workers and wounding eleven.[2]

Locust Grove Mine

Locust Grove was owned by the West Virginia and Pittsburgh Coal Company. This mine was the location of another explosion. On June 11, 1914, shots were fired at the mine by unknown assailants, and a dynamite bomb was exploded at the mine entrance. It is likely that the attacks were the work of company employees taking part in a strike that had begun in September 1913, but the assailants were not caught.[3]

Sports

Colliers held several bareknuckle boxing championship matches in the late 1800s. There were many reasons for choosing Colliers as the site for these exhibitions. Because of the railroad running through the town, transportation was readily available. Even those who could not ride the passenger train and had to rely on freight trains for transportation benefitted, as nearly all freight trains stopped at Colliers for coal and water.[15]

The profitability of the town was also a major factor. With its mining industry, Colliers provided its citizens with excess money that could be used for the customary collection that was taken for the loser of the fight, who would otherwise win no prize money.[15]

The most important reason for Colliers to be chosen was its proximity to state lines. As public boxing matches were prohibited in both West Virginia and Pennsylvania, a relatively small town near the state line had to be used. The participants in the fight were able to easily cross over into Pennsylvania if the authorities interfered, and could cross back if Pennsylvania authorities came. For this reason, many dog and chicken fights were also held in Colliers.[15]

On March 4, 1873, the bareknuckle boxing American lightweight championship match between Harry Hicken and Bryan Campbell took place at Colliers Station. After twenty-four rounds, both fighters fell and chaos descended on the crowd. The fighters’ seconds, Ned O’Baldwin and Owney Georghagen, began to fight, and O’Baldwin was beaten with a pistol by a spectator. The fight was broken up, and the referee declared Hicken to be the winner.[16]

In 1880, the bareknuckle boxing world heavyweight championship match between Paddy Ryan and Joe Goss was held in Colliers. The match was prevented from occurring in Canada with extra border control and undercover detectives in America.[17] Pennsylvania authorities also prohibited the match in Allegheny County, and Joe Goss assured the authorities that it would take place outside the county.[18]

The fight lasted for 87 rounds. Joe Goss, the reigning champion, was much more experienced than Ryan, who had never fought a championship match before. Ryan suffered many injuries to his head, and much of his body was bruised. However, due to Goss’s advancing age, he was unable to continue the fight, leaving Ryan the victor.[15]

References

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Colliers, West Virginia

- "Collier's Station, WV Mine Disaster, Nov 1894". Newark Daily Advocate Ohio. November 21, 1984.

- "Coal Miners Under Fire". New York Times. June 12, 1914.

- Caldwell, Nancy L. (1975). A History of Brooke County. Parsons, West Virginia: McClain Printing Company.

- "Colliers". American Towns. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- Eckert, Allan W. (1995). That Dark and Bloody River. New York, NY: Bantam Books.

- Reed, Amanda Fluharty (1994). The History of Collier School and Some Other Schools in the Cross Creek District, Brooke County, West Virginia.

- "Mountaineer Metal Products - WV". Manta. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- "Colliers Primary School". Trulia. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- https://k12.niche.com/rankings/public-elementary-schools/best-overall/s/west-virginia/

- https://nationalblueribbonschools.ed.gov/awardwinners/winning/17wv100pu_colliers_primary_school.html

- https://nationalblueribbonschools.ed.gov/education-secretary-devos-announces-recipients-of-the-2017-terrel-h-bell-awards-for-outstanding-school-leadership/#.Wfe7sGhSzIV

- "About Us". Open Door Baptist Church. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- "Explosion in a Coal Mine". New York Times. November 22, 1892.

- "Ryan & Goss Fought at Colliers". Brooke County Historical Review. September 1983.

- "The Prize Fight". Wheeling Register. March 5, 1873.

- "Trying to Prevent Prize Fights". New York Times. May 8, 1880.

- "Joe Goss-Paddy Ryan Championship Fight". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer. June 1, 1880.