Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary

Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary is a marine sanctuary located off the coast of California. It protects an area of 1,286 sq mi (3,331 km2) of marine wildlife. The administrative center of the sanctuary is on an offshore granite outcrop 4.5 sq mi (12 km2) by 9.5 sq mi (25 km2), located on the continental shelf off of California. The outcrop is, at its closest (Point Reyes), 6 mi (10 km) from the sanctuary itself.[2]

| Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Cordell Bank, California, United States |

| Coordinates | 38°04′00″N 123°22′04″W[1] |

| Area | 1,286 sq mi (3,330 km2) |

| Established | 1989 |

| Governing body | NOAA National Ocean Service |

| cordellbank | |

Cordell Bank is one of the United States' 13 National Marine Sanctuaries that protect and preserve ocean ecosystems in the U.S. Cordell Bank is a seamount approximately 50 miles (80 km) northwest of San Francisco where the ocean bottom rises to within 115 feet (35 metres) of the surface.[3] The seamount was discovered in 1853 by the U.S. Coast Survey, and named for Edward Cordell, who surveyed the area more thoroughly in 1869. It was extensively explored and described during 1978–86 by Robert Schmieder, who published a monograph about it [Schmieder, 1991]. It has been protected as a sanctuary since 1989. The protected area encompasses 526 square miles (1347 km2) of ocean.

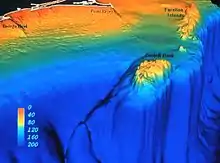

The unique blend of ocean conditions and undersea topography creates a rich and diverse underwater ecosystem. A subsurface island rises from soft sediments covering the continental shelf. The upper pinnacles reach to within 115 ft (35 m) of the surface, and the average depth is 400 ft (122 m). The sanctuary serves as a breeding ground for migratory marine mammals, birds, and fish. The prevailing California Current flows southward along the coast, causing an upwelling of nutrient-rich water that provided the foundation for the area's marine ecosystem.[2]

Sanctuary regulations prohibit extraction of hydrocarbons (oil, natural gas), the removal of benthic (bottom-dwelling) organisms, discharge of wastes, and removal of cultural resources. Recreational SCUBA diving is not recommended in the sanctuary due to depth and currents.

Geological setting

Cordell Bank was originally created 93 million years ago, as a member of the Sierra Nevada. The grinding of the plates at the San Andreas Fault, with the Pacific Plate moving north and the North American Plate moving south, parts of the Sierra Mountains were sheared off and carried northwards, including Cordell Bank. Eventually this grinding carried Cordell Bank to its present location opposite Reyes Point. Cordell Bank is still moving, by an average of 3 cm (1 in) per year.[4]

Between 20,000 and 15,000 years ago the sea level in the area was 360 ft (110 m) below the current level, leaving most of Cordell Bank exposed and making it a true island. Today the bank rises out of soft sediment, deposited on the bank more recently by coastal erosion. Within just 7 mi (11,265 m) of Cordell Bank, the continental shelf drops to over 1 mi (2 km) deep.[4] The seamount is largely composed of granite.

History

Coastal California has a rich history of marine utilization by Native Americans and early settlers. Cordell Bank was a mystery prior to the 19th century because neither the Miwok natives nor the settlers had any incentive to venture far out from shore, when food resources were available close to shore. Many European mariners sailed right over Cordell Bank without even knowing it was there.[5]

In the later half of the 1800s there was a strong incentive to survey the coast of California so as to promote maritime safety. Cordell Bank was discovered in 1853 by George Davidson of the US Coast Survey during a mapping expedition on California's north coast.[5][6]

In 1869 Edward Cordell (the reserve's namesake) was sent to collect additional information on a "shoal west of Point Reyes". He found the area by following the numerous birds and marine mammals. To measure the depth, Cordell lowered a lead weight into the water until it hit the bottom and then measured the length of the line on its return to the surface.[6] The area was considered a productive fishing area, but not much was discovered about its marine life until an expedition in 1977.[5]

NOAA carried out a detailed multibeam echosounder survey of the area in 1985 from aboard the R/V Davidson.[6]

The expedition was led by a non-profit research group, Cordell Expeditions.[6] Over the next 10 years, scores of underwater dives documented the organisms living in, on, and around the bank. The efforts gave rise to an understanding of the biodiversity of the bank, and were instrumental in the decision to make it a sanctuary.[5]

Expansion

A bill (H.R. 5352) was proposed to Congress by Representative Lynn Woolsey to expand the size of the Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary and the neighboring Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary by 1,094 square miles (2,830 km2).[7]

In 2012, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration proposed an expansion of the borders of the sanctuary, along with expansion of the Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, to include an additional 2,700 square miles, reaching to Point Arena.[8]

Expansion was passed March 2015.[9]

Biology

26 species of marine mammals, including whales, dolphins, seals, and sea lions, are known to frequent the waters of the sanctuary. In addition, Cordell Bank is one of the most important feeding grounds in the world for the endangered blue and humpback whales; these species travel all the way from their breeding grounds in coastal Mexico and Central America to feed on the krill that aggregate near the bank. Another unique species is the Pacific white-sided dolphin (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens), which can be seen in large numbers. Other visitors include California sea lions (Zalophus californianus), northern elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris), northern fur seals (Callorhinus ursinus), and Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus), all of which are attracted to the abundance in krill, squid, and juvenile fish.[10] Leatherback sea turtles also inhabit sanctuary waters.

Cordell Bank is also a major foraging ground for passing seabirds. Known as the "Albatross capital of the world," 5 of the 14 major species of albatross have been documented there. The two most common are the black-footed albatross (Phoebastria nigripes) and sooty shearwater (Puffinus griseus). It is also one of the few places to see a short-tailed albatross (Phoebastria albatrus), which is extremely rare; the species was thought to have gone extinct after World War II. Currently the world population hovers at around 1000 individuals.[10]

Cordell Bank is also known for its abundance of fish. Flatfish, most notably sanddabs, make their home on the mud of the seafloor in the sanctuary. Both solitary and schooling fish find refuge for predators among the bank's rocky pinnacles. Cordell Bank supports more than 246 species of fish, including 44 species of rockfish, ranging in size from the 8-inch pygmy rockfish to the 3-foot (0.91 m) yelloweye rockfish.[10]

Although far from shore, sport fishers prize Cordell Bank as a fishing spot, and regularly venture out from shore to catch albacore and salmon.[10]

Ecologic cycle

This unusual granite mountain is surrounded on three sides by deep waters, which allows the flow of deep nutrient-rich waters over relatively shallow waters with sufficient light to support photosynthesis.

The ecological cycle at Cordell Bank can be divided into three oceanographic seasons. During the spring, strong northwestern winds push the water southward along the California coast. Gale winds and the Earth's rotation drive surface water away from the shore, only to be replaced by an upwelling of more nutrient-rich waters from offshore. this contributes to the growth in numbers of phytoplankton, which are the foundation of the marine food web, in turn leading to a rise in the food supply, and thus numbers, of the organisms higher up the chain.[11]

During the late summer and fall seasons, the coastal winds that stirred up the deeper waters die down, and the northward-flowing Davidson Current prevails, bringing warm but nutrient-poor water from the south.[11]

During the winter storm months, the sea is dominated by rough weather, which mixes the deeper water with that above. The temperature on top of the continental shelf mixes, and the temperature, salinity, and the concentration of nutrients in them are assimilated.[11]

References

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary

- "About the Sanctuary". NOAA. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- "Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary" at NOAA.gov

- "Natural Natural Environment: Geologic History". NOAA. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- "Natural The History of Cordell Bank". NOAA. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- Schmieder, RW (1985). "The expeditions to Cordell Bank". In: Mitchell, CT (ed). Diving for Science…1985. Proceedings of the Joint American Academy of Underwater Sciences and Confédération Mondiale des Activités Subaquatiques annual scientific diving symposium 31 October - 3 November 1985 La Jolla, California, USA. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- Woolsey, Lynn C (8 October 2004). "H.R.5352 - Gulf of the Farallones and Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuaries Boundary Modification and Protection Act". Congressional Bills 108th Congress: From the United States Government Printing Office. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- "Natural Environment: Biological Resources". NOAA. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- "Natural Environment: Oceanographic Seasons". NOAA. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

Works cited

- "A National Marine Sanctuary: Cordell Carpenter Bank," Published by the National Marine Sanctuary Program of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

- Schmieder, Robert W., 1991, Ecology of an Underwater Island, Published by Cordell Expeditions, Walnut Creek, CA, http://www.cordell.org. See also: Schmieder Bank

- Stallcup, Richard. 1990. Ocean Birds of the Nearshore Pacific, Point Reyes Bird Observatory, Stinson Beach, CA. 214 pp.