Croatia during World War I

The Triune Kingdom of Croatia, Slavonia and Dalmatia was part of Austria-Hungary during World War I. Its territory was administratively divided between the Austrian and Hungarian parts of the empire; Međimurje and Baranja were in the Hungarian part (Transleithania), the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia was a separate entity associated with the Hungarian Kingdom, Dalmatia and Istria were in the Austrian part (Cisleithania), while the town of Rijeka had semi-autonomous status.

| 1914–1918 | |

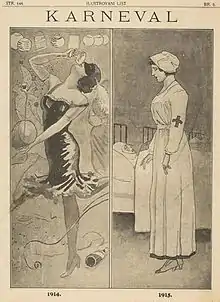

1915 caricature from the Carnival magazine shows the sharp contrast of pre-war and wartime life in Zagreb | |

| Monarch(s) | Franz Joseph I (1914–1916) Charles I (1916–1918) |

|---|---|

| Leader(s) | Civil Bans: Ivan Skerlecz (1913–1917) Antun Mihalović (1917–1919) |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Croatia |

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The unification of Croat-inhabited territories was a fundamental problem that had not been resolved with the creation of Dual Monarchy in 1867. An excess of political problems within Austria-Hungary itself, exacerbated by the earlier Balkan Wars, led to a state of unrest, strikes, and series of assassinations within Croatia at the outbreak of World War I. Croatian policy amounted to either trying to find the best solution whilst staying within the empire (such as Trialism in Austria-Hungary or Austro-Slavism) or unifying with Serbia and Montenegro (namely Yugoslavism), thereby forming a South Slavic state. Political action was extremely limited during the war, with much of the power being held by the Austro-Hungarian military authorities. Calling for the creation of a unified South Slavic state was thus equated with treason.

During World War I, Croats fought mainly on the Serbian Front, the Eastern Front and the Italian Front, against Serbia, Russia, and Italy, respectively. A small number of Croats also fought on other fronts. Some Croats, mostly Croatian Americans or Austro-Hungarian Army deserters, fought on the side of the Allies. Croatia suffered great human and economic losses during the war, which were exacerbated by the outbreak of Spanish flu pandemic in 1918.[1] Although Croatians were less than 10% of the population, they accounted for approximately 13-14% of the Austro-Hungarian military conscripts. Croatian military losses likely amounted to 190,000 people, while some sources list about 137,000 military and 109,000 civilian casualties.[2]

With Austria-Hungary's imminent defeat and collapse, on 29 October 1918, the Croatian Parliament declared the country's secession from the empire. Croatia subsequently joined the short-lived State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, which was united with Serbia to form the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes on 1 December 1918.

Situation in Croatia

Outbreak of War

Inter-ethnic tensions in Croatia increased following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on 28 June.[3] The evening of the assassination, Croats held commemorative parades and gatherings, carrying pictures of the fallen heir to the throne and Croatian flags adorned with black flora. Members of the Party of Rights were angered by his assassination as Franz Ferdinand had expressed sympathy for Croatian interests in the past.[4] Members of the Party of Rights used some minor provocation and the atmosphere of bitterness to orchestrate anti-Serb demonstrations. After someone threw stones at the commemorative parade, the party's followers demolished Serb-owned stores and cafés, as well as the gathering places of pro-Yugoslav politicians.[5][6] MPs of the ruling Croatian-Serbian Coalition were physically attacked.[7] Members of the Social Democratic Party of Croatia and Slavonia held a protest against this violence.[8] At the same time with large anti-Serbian riots in Vienna, Budapest and serious incidents in Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina, where many were wounded and murdered, conflict with the Yugoslav oriented citizens and associations, and Serbian associations and clubs, occurred in many Croatia towns. It was then when the building of the Serbian society Dušan silni in Dubrovnik was destroyed. This was all triggered by the fact that Franz Ferdinand's assassin, Gavrilo Princip, was an ethnic Serb.[9] Riots were reported in Zadar, Metković, Bjelovar, Virovitica and Konavle, where protesters burned the Serbian flag. In Đakovo and Slavonski Brod, riots become so violent that the Austro-Hungarian Army was asked to intervene.[10] In addition, a curfew was imposed Petrinja. In Vukovar and Zemun, the police managed to prevent more clashes. Most Serbs in Croatia approved the assassination. Cases of provocation, such as showing images of King Peter, joy, insults and celebrations, were reported.[11][12] Fourteen Serbs were arrested in Zadar for celebrating the assassination.[13] Some pro-Yugoslav politicians, such as Ante Trumbić[14] and Frano Supilo,[15] decided to emigrate to avoid prosecution. The Croatian sculptor and architect Ivan Meštrović emigrated to the United States.[16]

An extraordinary session of the Croatian Parliament, which was convened to read a loyalty oath to the Empire and statement of condolence, was interrupted with accusations and recriminations against ruling Croatian-Serbian coalition by the members of Party of Rights (HSP). The HSP politician Ivo Frank allegedly threatened the Serb representatives with a revolver.[17] On 26 July, partial mobilization was announced. The next day, ban Iván Skerlecz issued a special regulation abrogating Ivan Mažuranić's 1875 Law on Freedom of Assembly. After war was declared on 28 July, many pro-war demonstrations were held in Zagreb. The arrival of recruits to the Zagreb barracks was welcomed with approval. People shouted to the soldiers: "Long live the Croatian army", to which the soldiers would respond: "Long live Croatia, long live the Croatian King [Franz Joseph]".[18]

Since the last conflict that Croatia was involved had taken place in 1878, and since all of Europe had enjoyed almost 50 years of peace and relative stability, the war was met with shock and disbelief.[19] Food prices immediately increased so the government had to freeze them. All associations except firefighting and charity were closed. Shortly thereafter, many pro-Yugoslav politicians and activists, such as Ivo Vojnović, Ivo Andrić, Grga Angjelinović and Oscar Tartaglia, were arrested. Most were freed in 1915, and no later than 1917, following the Emperor Charles' adoption of a general amnesty for political prisoners. He amnestied all political prisoners after coming under strong pressure from the international public and in preparation for the conclusion of a separate peace treaty with the Triple Entente. Most of the territory of modern-day Croatia, with the exception of Eastern Syrmia and some Dalmatian islands (Palagruža, Lastovo), was not affected by military operations, but 60,000 residents of Pula and the surrounding area were forced to relocate in 1915 to refugee camps in Austria, Bohemia and Slovenia because of the proximity of war, and the security of the naval port. Many of them died in those camps of diseases and hunger. In Istria, martial law was imposed. The Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia had a difficult political situation. During all four years of war, Kingdom was in danger of seduction of the dictatorship of Military Commissariat which was constantly trying to seize power from the Croatian Parliament. Party of Rights supported dictatorship because they hoped that they would become its levers.[20]

The economic situation was very bad since nearly a million people from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina was mobilized.[21] Nevertheless, the involvement of Russian and Serbian prisoners of war, who were ascribed to agricultural estates and factories for forced labor, was helping out. There was a shortage of products, as evident from the fact that the copper roofs of Dubrovnik Cathedral and Croatian State Archives palace were removed and warm in the ammunition. Same fate befell the Jaruga Hydroelectric Power Plant on the river Krka near Šibenik. The bread was received only with food stamps, while textile goods, even those of nettles, were completely gone. There was so little vegetable that there were no food stamps for it, so potatoes and beans were given away by the government from time to time. Women and children would wait all night at the Ban Jelačić and Preradović squares to get their 1⁄4 kg of potatoes or beans that were given per person.[22]

Charity campaigns

Charity campaign I Gave Gold for Iron (Dadoh zlato za željezo) was conducted in 1914. People donated their gold jewelry in exchange for iron rings. Donated gold was used for supporting families of killed soldiers.[23]

In October 1914, the Government Commissioner for the Organization of Voluntary War Nurse Service, with the approval of High Royal Government, started campaign Gold for Iron (Zlato za željezo) in order to gather "gifts in the form of golden items, cash money, and other valuables". After the assessment and with the written confirmation, donors were given an iron ring worth as the given donation, with the minimum value of the donation being 5 krones. The purpose of this charity campaign was to raise money for the families of killed soldiers "who are natives of these Kingdoms and who have left their families with lack of supplies." The center of the organization was in Zagreb, while collecting was carried out at the premises of the First Croatian Savings Bank in Ilica no. 5, in its subsidiaries or by an authorized person in the smaller towns. The rings had inscription "I Gave Gold for Iron 1914" and were protected by the stamp of the Commission for the Organization of Voluntary War Nurse Service.[24] In addition, in the year 1915, citizens of Zagreb could hammer a nail into the trunk of the lime tree at Nikola Šubić Zrinski Square for a symbolic amount of money, thus collecting resources for families of soldiers who were killed in the war.[25] This action took place in other Croatian cities as well; in Pula donors could hammer a nail into the lighthouse, and in Jastrebarsko in wooden hawk.

Avenue of chestnut trees in the main street of Sinj, which is used as the racecourse of Sinjska alka, was planted in memory of the recruited soldiers who went to war in 1917. The number of trees equals the number of men who were recruited.[26] Many members of the nobility were engaged in humanitarian work as well. Marija Janković, married Adamović, a noblewoman from Janković family, donated a large portion of her wealth for buying medication for poor. She was also personally helping wounded soldiers in Drenovci.

Taking care of starving children

Long war for which Austria-Hungary was not prepared, and drought, caused hunger and famine in 1916 and especially 1917. People, especially children, started dying, mostly from starvation. Therefore, the Zagreb Central Committee for the Care of Families of Mobilized and Killed Soldiers, began a large humanitarian action of relocation of children from Istria to the north Croatia.[27] This charity campaign was accepted by the Franciscans of Herzegovina as a lifeline for (Catholic) children, which was initiated and implemented by Fra Didak Buntić.[28] During 1917 and 1918, about 17,000 children from Herzegovina were taken care for in Croatia and Slavonia.[29] It was also a lifeline for children from Bosnia, Dalmatia, and Slovenia. This campaign, that was managed from Zagreb by dr. Josip Šilović, Đuro Basariček and Zvonimir Pužar, became massive. During the War, more than 20,000 children arrived to the northern Croatia, mostly to Bjelovar-Križevci County.[30]

Censorship

After the beginning of War, Government introduced a system of extraordinary legal measures in the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia. Those laws were mainly focused on control over the press. In cases where journalists violated the rules of military censorship, the military administration would recruit them and send them to the battlefield.[31] The military censorship canceled "Hrvat" and "Hrvatski pokret", newsletters of the Croatian Party of Rights. Despite censorship, public interest in newspapers has increased significantly. At the end of the war, in 1918, daily circulation of all newspapers in Zagreb increased to 150,000 copies, which was five times the pre-war editions.[32]

Rebellion and desertion

Under the influence of the Russian October Revolution, the spread of Lenin's ideas, but also because of the desperate situation of Croatian soldiers and sailors and senseless prolongation of war operations, desertion, rebellion and desecration of soldiers and sailors become common from the beginning of 1917. There were many anti-war protests and desertions in the port town of Pula.

Protest of 11,000 arsenal workers who were seeking truce, higher wages and better nutrition, broke out in 1918. Crew of the seaplane K-307 deserted and ran from Kumbor to Brindisi. Crew of torpedo boat T-11 ran away with the boat from Šibenik harbor to Kingdom of Italy. Sailors Koucký Frantisek (Czech) and Ljubomir Kraus (Croat) tried to escape from Pula with a torpedo boat T-80 but were betrayed, sentenced to death and executed. Sailors from the warships Erzherzog, Prinz Eugen and Aspern were canceling their obedience in support of the workers' protests. 35 members of Pula seaplane base were punished with long prison terms because of the disobedience.[33] One of the biggest rebellions was the Cattaro Mutiny that occurred in Bay of Kotor on 1 February 1918. In the northern Croatia, deserters from the Royal Croatian Home Guard, known as Green cadres, were randomly looting and burning down nobility castles and estates. It is estimated that the number of Green cadres was about 50,000 at the end of the war. Prohibited mockery: Care Karlo i carice Zita, što ratujete kad nemate žita?! ("Emperor Karl and Empress Zita, why do you make war when you have no grain?!") was very popular among soldiers.[34]

Spanish flu pandemic

In July 1918, first cases of Spanish flu, which killed more than 20 million people worldwide, were reported in Croatia. On average, 60 people were dying in Zagreb per week. In the most difficult period of the epidemic that number has grown to more than 200 people, with a peak in the second week of December, when the number increased to 264. In less than four months, Spanish flu took 700 lives in Zagreb alone, and probably tens of thousands on the whole Croatian territory. Contemporaries evaluated that nearly 90% of the Croatian population was affected in the second half of 1918. Estimate of 15,000 to 20,000 victims in Croatia should be taken as the lower limit of the number of victims of the epidemic.[35]

In 1918, during the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, a period of anarchy and general insecurity began in Croatia. Serbian army entered Slavonia under the pretext of introducing order. It was supported by the French colonial units (Vietnamese, Senegalese...).

Croats on the battlefield

In the First World War, Austria-Hungary fought on the side of the Central Powers. Croatian soldiers fought in the Balkans, Galicia, and since 1915, on the Italian front. Since July 1918, some Croatian troops fought on the Western Front as part of 18th Corps:[36][37] 31 hunting battalion, two squadrons of the 10th Hussar Guard Regiment[38] and artillery units in the Battle of Verdun. Croatian gunners fought as part of the Austro-Hungarian artillery batteries in Sinai and Palestine as assistants to the Turkish forces.[39] The complexity of administrative fragmentation of Croatian lands affected the military organization, so the soldiers from the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia fought as part of 13th corps of the Austro-Hungarian Army and the 42nd Home Guard Infantry Division known as the Devil's Division of the Royal Croatian Home Guard. Soldiers from the Kingdom of Dalmatia were members of the 22nd Imperial and Royal Regiment, Zadar 23rd Imperial and Royal Regiment, Dubrovnik 37th Home Guard Regiment, and elite unit of Dalmatian Terrestrial Shooters. Istrians served in the 5th Imperial and Royal Home Guard Regiment and the 87th Imperial and Royal Regiment, while people from Međimurje served in 20th Royal Hungarian Regiment and 48th Imperial and Royal Regiment. In addition, Dalmatians and Istrians were recruited to the Austro-Hungarian Navy.

At the beginning of the war in the summer of 1914, the general mobilization of Zagreb 13th Corps (including 42nd Home Guard Division) in the 5th Army and the Dalmatian-Herzegovinian 16th Corps under the 6th Army, were sent to Serbia, while Istrian and Međimuje troops were sent to Galicia.[40] On 23 May 1915, 16th Corps was transferred from Serbia to the newly opened Italian Front, where it remained until the end of the war.[41] Intention of the General Staff was clear – Croats from Dalmatia had a motive to fight against Italy, since they were directly threatened by the Italian plans of taking the eastern Adriatic coast according to the Treaty of London.[42] On 27 February 1918, Zagreb 13th Corps was transferred to the battlefield of the Isonzo where it remained until the end of the war. At the end of the war, 84th Home Guard Brigade held a defensive position at Monte Groggio, while 83rd Brigade was in reserve near Belluno. On 22 October 1918, 83rd Brigade refused to replace the 84th Brigade at the position which was a sign of mass disobedience that was happening in the Austro-Hungarian Army. After the retreat from the Monte Groggio on 30/31 October 1918, 84th brigade entered Puster Valley near Bruneck. It was transported together with the 83rd Brigade from Carinthia to Croatia.[43]

Croats that were captured on the Italian and Galician battlefields often ended up in the so-called Yugoslav Legion, where they continued to fight on the Macedonian front. Among them were cardinal Aloysius Stepinac, ban Ivan Šubašić, and composer Ivo Tijardović. Croatian painter Vladimir Becić joined the Serbian army shortly before the outbreak of war.[44]

Croatian emigrants

Part of Croatian emigrants helped the work of the Yugoslav Committee, while others opposed its idea of creating a unified South Slavic state. Committee ideas got deep roots among the Croatian diaspora, especially the one in South America. After they heard the news of the war, they reacted by spontaneously gathering so they soon found themselves under the patronage of the Yugoslav Committee. The link between the Committee and emigrants was established by Committees member Mićo Mičić and organized by the representatives of the United Yugoslavian (Nationalist) Youth, Milostislav Bartulica and Ljubo Leontić. Emigrants were of great importance for the Committee for these reasons: emigrants were giving legitimacy to the Committee that it could not get out of its homeland; emigrants were covering Committee's expenditure giving it kind of freedom in political action in relation to the Serbian government which was trying to degrade it to its body for promotion; emigration was basis for recruitment of the members of imaginary Yugoslav Legion which fought on the Macedonian Front. Nevertheless, the only real effect was material support. Despite the legitimacy that it got from emigrants, the Committee was not recognized by the Triple Entente as a representative of the South Slavs of the Empire, and emigrants generally did not come to fight on the Macedonian Front.[45]

Since they came from Austria-Hungary, the enemy of the country, hundreds of Croatian emigrants in Canada, together with other co-citizens, were detained in concentration camps and used as forced labor in the most remote regions of Canada. At the same time, they were stripped of all their assets. In 2011, Croatian Consul to Canada Ljubinko Matešić marked the graves of Croats who died during captivity.[46][47]

Internal political developments

Discontent and demands for resolving the Croatian question were increasingly growing. Its solution depended on whether the Empire would survive as a country or not. When the war broke out, there were three possible solutions for the Croatian question:

- staying in the reorganized Empire,

- creation of the independent Croatian state,

- entering into a unified South Slavic state (excluding Bulgarians).

The last two solutions predicted the collapse of the Empire. The first solution had the best possibility at the beginning of the war because non of the superpowers wanted the dissolution of the Empire but rather its reconstruction and federalization. Creation of a Trialist monarchy generally prevailed on the Vienna court.[48] The creation of the independent Croatian state had the slightest chance in the given international circumstances. Therefore, Croatian politicians opted for the other two solutions during the war.

Since 1913 parliamentary election, Croatian-Serbian coalition (HSK) had the majority in the Croatian Parliament. Its leader was Svetozar Pribičević who advocated the creation of a unified South Slavic state. HSK cooperated with the Hungarian government, against Austria, and did not make any public statements about the reorganization of the Empire. Some opposition parties gathered in a temporarily formed alliance, Croatian Statehood Democratic Bloc, which was formed after part of moderate members of the Party of Rights excepted the Yugoslav idea. They all generally shared the idea of trialism or creation of the Croatian Kingdom which would have a high degree of autonomy within the Empire.

Almost throughout the war, Stjepan Radić believed in the success of the Empire and a favorable solution of the Croatian problems within it. In 1914 he stated: "Victory of Austria-Hungary would be a disaster for all the nations of Austria-Hungary, with the exception of the Germans and Hungarians. However, the disintegration of the Austria-Hungary would be a disaster for all nations of the Empire, even Germans and Hungarians. For us Croats, it will be the only luck if Austria-Hungary would be totally defeated, but stay together afterwards."[49] However, as the end of the war approached, he was dissatisfied with the unfavorable position of Croatia so he changed his mind, stating in September 1917 that he would be the first one to shout "Down Habsburgs!" if something did not change.[50]

Step towards the unification of the Croatian lands has been made pro forma in 1916. Vice-ban Vinko Krišković, who was tirelessly working to strengthen Croatian position within the Empire, managed to persuade the emperor to guarantee the territorial integrity of Croatia, Slavonia and Dalmatia in his inaugural oath on New Year's Eve of 1916 in Budapest. This prevented emperor to mention otherwise agreed the text of the oath before the Imperial Council in Vienna in 1917, which stated that Dalmatia was an Austrian crown land. Furthermore, Krišković negotiated with Emperor the real unification of the Croatian lands, including Bosnia Herzegovina. Despite the Emperor's preferences, it turned out that some politicians from Dalmatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina were extremely reluctant about that idea, with some even suggesting that Croatia should be annexed to Dalmatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina instead.[51]

.png.webp)

Representatives of Croats from Dalmatia and Istria and Slovenes, gathered in an Yugoslav parliamentary club in the Imperial Council, after the death of Emperor Franz Joseph in 1916, submitted May Declaration in which they called for reorganization of the Empire on the trialist principles. This plan included the creation of a third unit that would include all South Slavic countries within the Empire (Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Vojvodina). Some prominent Croatian politicians, such as Vjekoslav Spinčić, Josip Smodlaka and Ivo Prodan were members of the Club.[52] Declaration was presented by Anton Korošec in late May 1917. Yugoslav Committee and Ante Trumbić were not satisfied with the decision of the Yugoslav club to stay in the Empire.

Stješan Radić, as representative of the Croatian Party of Rights and Croatian Peasant Party, stated in the Parliament on 7 February 1918: "We want to build our national democratic state of Croatia together with the Slovenians in which our brothers Serbs would have all the rights that we have. If Serbs would oppose this Croatian state, we will try our best to revive it without them, even against them, because we are convinced that without the unity with these Slovenians and without the totality of historic Croatia, Bosnia and Dalmatia, Croatian nation will not prosper, nor survive."

On the other hand, Starčević's Party of Rights took a leading role in bringing together all the parties and groups that were in favor of creating a unified South Slavic state. Meeting of representatives from the South Slavic states of the Empire, on which the Zagreb resolution was accepted, was held in Zagreb on 2 and 3 March 1918. Resolution signatories asked for creation of a democratic South Slavic state; "We are asking for independence, unification and freedom in our unique national country in which the noble qualities of a single nation with three names, Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, would be preserved, and if desired by the component parts respect national statehood continuity of historic and political territory with full equality of tribes and religions."[53] One of the conclusion was that the creation of national organizations that would be merged into a single body had to start. These organizations were soon established in Dalmatia, Istria and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Stjepan Radić and representatives of the Croatian-Serbian coalition did not attend the meeting. Radić disagreed with the resolution, while HSK considered that it was too early for such meetings. National Council of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs was created on 5 October 1918 in Zagreb. HSK soon joined and in accordance with the majority in the Parliament took the final word. Anton Korošec (Slovene) was Council president, with vice-presidents being Ante Pavelić Sr. (Croat) and Svetozar Pribićević (Serb).

Another advocate of Trialist empire was the general Stjepan Sarkotić, war governor of Bosnia and Herzegovina. In the last days of the Empire he tried to persuade the emperor to annex Bosnia and Herzegovina and Dalmatia to Croatia. Emperor agreed in principle, but he left the final decision to the Hungarian government, but it was too late. In early October 1918, it was clearly visible that the Empire would collapse. In mid-October 1918, the United States rejected the idea of the autonomy of the southern Slavs within the Empire. Emperor Charles tried to prevent the inevitable so he issued manifesto on 16 October and proposed a reconstruction of the Empire into federation. The National Council of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs rejected emperors manifesto, and announced on 19 October that it would take control over the national policy.

Creation of unified South Slavic state was announced publicly for the first time. On 29 December 1918, Croatian Parliament unanimously adopted a conclusion on suspension of all constitutional ties with Austro-Hungarian empire. Croatia, Dalmatia and Slavonia with Rijeka were declared an independent state, which immediately accessed the newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. Parliament recognized National Council as a constitutional government. The decision on the form of government and the interior organization of State was given to the Constituent Assembly. Triple Entente did not recognize the newly created State, and because of the resistance of the Serbian government, they refused to recognize the legitimacy of Yugoslav Committee. This allowed the Italian army to begin the occupation of Croatian areas in accordance with the Treaty of London. Italian occupation of Dalmatia has prompted the government to seek unification with Serbia as soon as possible in order to get protection since their state did not have standing army. Request of the Dalmatian government and riots that broke out in the Dalmatian countryside forced the Central Committee of the National Council to speed up unification with the Kingdom of Serbia and Montenegro, despite strong opposition from Stjepan Radić.

Unification was declared on 1 December 1918, contrary to the instructions of the National Council, and without the consent of the Croatian Parliament. The new country was named Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.[54]

Victims

Writer Miroslav Krleža wrote about human losses before Christmas of 1915 in his book Zastave (Flags) (quoting credible news reports):: "25th Home Guard Infantry Regiment 14,000 dead, 26th Regiment 20,000 dead, 53rd Regiment 18,000 dead".[55] Total Croatian losses were around 190,000 people,[56] with some sources claiming 137,000 military and 109,000 civilian casualties.[57] 4,363 people were killed in Međimurje alone.[58] It's very hard to come by the accurate data since relevant documentations is scattered in archives in Vienna, Budapest and Belgrade. Between the census of 1911 and 1921, territory of Croatia and Slavonia lost nominally 5,359 residents or 0.2%, and in 1921 the ratio of women to men was 1,043 women per 1,000 men. During this period, increase of birth rate of 1.7% per year, occurred. Peter Grgec wrote in his war memoirs that the Croatian losses were hardest of all Austro-Hungarian nations.[59]

References

- Proleksis enciklopedija-Hrvati

- https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/233073 Hrvatska u Prvom svjetskom ratu - Bojišta, stradanja, društvo (Croatia in WWI, Battlefields, losses, society); Filip Đukić, Marko Pavelić, Silvijo Šaur, in Croatian

- Agičić, p. 303

- The Economist-The Serbs and the Hapsburgs

- Agičić, p. 305

- Karaula, p. 274

- Karaula, p. 268.-269

- Agičić, p. 306.

- Demonstracije u Dubrovniku, Ilustrovani list, no. 29, Year I, 18 July 1914, Zagreb

- Agičić, p. 306.

- Agičić, p. 309.-310

- Karaula, p. 276.-278

- Karaula, p. 277.

- Krležijana – Ante Trumbić

- Hrvatska enciklopedija (LZMK) – Frane Supilo

- Krležijana – Ivan Meštrović

- Agičić, p. 313

- Agičić, p. 313

- Kovačić, Krešimir; 1963., Clochemerle u Zagrebu – humoristični zapisi iz vremena prošlih

- Karaula, p. 270.

- Matica hrvatska-Prvi svjetski rat kao terra incognita

- Kovačić, Krešimir; 1963., Clochemerle u Zagrebu – humoristični zapisi iz vremena prošlih

- Pedagoška djelatnost Hrvatskoga povijesnog muzeja-"Dadoh zlato za željezo"-Hrvatska u Prvom svjetskom ratu 1914.–1918.

- http://www.hismus.hr/hr/izlozbe/virtualne-izlozbe/patriotski-prsteni-zlato-za-zeljezo/ Hrvatski povijesni muzej-Patriotski prsteni–Zlato za željezo

- THE ESTABLISHMENT OF MEDICAL SCHOOL IN ZAGREB IN WORLD WAR I

- Turistička zajednica Splitsko-dalmatinske županije-Sinj, drvored kestena

- Kolar-Dimitrijević, Mira; 2007., Zbrinjavanje gladne istarske djece tijekom Prvoga svjetskog rata u Križevcima i okolici, Cris: časopis Povijesnog društva Križevci, Vol. VIII, No. 1 (2006.); p. 14-25

- "Zbornik Fra Didak – čovjek i djelo: Vlado Puljiz, "Prilike u Hercegovini i spašavanje gladne djece u Prvom svjetskom ratu"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- "Zbornik Fra Didak – čovjek i djelo: Marinka Bakula Anđelić i Dražen Kovačević, "Živi smo!"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- Kolar-Dimitrijević, Mira; 2007., Zbrinjavanje gladne istarske djece tijekom Prvoga svjetskog rata u Križevcima i okolici, Cris: časopis Povijesnog društva Križevci, Vol. VIII, No. 1 (2006.); p. 14-25

- Ivan Bulić: Miroslav Krleža o Hrvatskoj u Prvome svjetskom ratu (Između kronike i interpretacije)

- Kovačić, Krešimir; 1963., Clochemerle u Zagrebu – humoristični zapisi iz vremena prošlih

- Ugo Matulić: "Mate Brničević u pobuni mornara u Boki Kotorskoj: Početak sloma Austro-Ugarske Monarhije"

- Veliki rat za još veće prešućivanje, Novosti, 12. studenoga 2011.

- Hutinec, Goran; 2006., Odjeci epidemije "španjolske gripe" 1918. godine u hrvatskoj javnosti, Radovi Zavoda za hrvatsku povijest, Vol.38 No.1 Studeni 2006.; p. 227-242

- Glaise von Horstenau, Edmund: Österreich-Ungarns letzter Krieg, 1914 – 1918 Vol. 7.: Das Kriegsjahr 1918

- Vladimir Huzjan, Raspuštanje Hrvatskog domobranstva nakon završetka Prvog svjetskog rata, Časopis za suvremenu povijest, 37/2005., no. 2, p. 452-460

- The Austro-Hungarian Army 1914–18 for collectors of its postal items, By John Dixon-Nuttall; Chapter 6 App. H: Cavalry units

- Slavko Pavičić, Hrvatska vojna i ratna poviest i Prvi svjetski rat, p. 664-665, p. 672-681

- Order of Battle – Galicia August, 1914

- The Austro-Hungarian army 1914–18 for collectors of its postal items, By John Dixon-Nuttall; Chapter 6 App. C: Korps

- Vojna povijest, Zagrebačke akcije za talijansko ratište

- "Vojna enciklopedija", second edition, II volume, Vojnoizdavački zavod, Beograd, 1973.

- Nina Ožegović: Nepoznati crteži Vladimira Becića: Ratna tajna slikarskog klasika, Nacional, br. 655, 2 June 2008; pristupljeno 3. ožujka 2014.

- Goran Miljan, Ivica Miškulin: Povijest 4, udžbenik povijesti za 4. razred gimnazije, Zagreb, 2009., ISBN 978-953-12-1096-6

- Stan Granić: Croats who died during WWI internment in Canada Remembered, Croatian Chronicle

- croexpress.eu-Prije točno 102 godine: Umro A.G. Matoš, gorljivi pravaš, 'Bunjevac podrijetlom, Srijemac rodom"

- Vinko Krišković: Izabrani politički eseji, Priredio Dubravko Jelčić, MH, SHK, Zagreb, 2003.

- Karaula, p. 271.

- Ljubomir Antić: Prvih sto godina Hrvatske seljačke stranke, HIZ, Zagreb 2003

- hkv.hr; Davor Dijanović: Vinko Krišković – intelektualac i ideolog demokratske orijentacije

- Goran Miljan, Ivica Miškulin: Povijest 4, udžbenik povijesti za 4. razred gimnazije, Zagreb, 2009., ISBN 978-953-12-1096-6

- http://www.matica.hr/hr/334/Prvi%20svjetski%20rat%20i%20Hrvati/ Matica hrvatska, HR, 2/IV Ljubomir Antić: Prvi svjetski rat i Hrvati

- Hrvatska enciklopedija (LZMK) – Hrvati/Povijest: Hrvatska u XIX. i na početku XX. st

- Krleža, Miroslav: Zastave, novel in five books, book no. 3, Naklada Ljevak, Zagreb, 2000.

- Vjesnik.hr, 10.09.2004: Prvi svjetski rat kao terra incognita

- Nenad Jovanović: Veliki rat za još veće prešućivanje, Novosti, Broj 621, 12. studenog 2011.

- vecernji.hr-U Prvom svjetskom ratu poginulo čak 4363 Međimuraca

- Ivica Zvonar: Zapisi Petra Grgeca o prvom svjetskom ratu i Podravini u ratnom razdblju, Podravina, sv. 11, no 21, p. 36 – 46 Koprivnica 2012.

Literature

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Croatia in World War I. |

- Agičić, Damir: "Civil Croatia on the Eve of the First World War (The Echo of the Assassination and Ultimatum)", Povijesni prilozi 14, p. 301–317

- Bilandžić, Dušan: "Hrvatska moderna povijest", Zagreb: Golden marketing. ISBN 953-6168-50-2

- Graljuk, Boris: "Bojišnice i grobišta hrvatskih vojnika na karpatskom ratištu u Prvom svjetskom ratu", Riječi, časopis za književnost, kulturu i znanost MH Sisak, 1-3/2013, p. 4–32

- Karaula, Željko: "Sarajevski atentat – reakcije Hrvata i Srba u Kraljevini Hrvatskoj, Slavoniji i Dalmaciji", Radovi Zavoda za hrvatsku povijest 43 (1): p. 255–291.

- Krizman, Bogdan: Hrvatska u Prvom svjetskom ratu – Hrvatsko-srpski politički odnosi, Globus, Zagreb. ISBN 86-343-0243-1

- Macan, Trpimir: "Povijest hrvatskog naroda", Nakladni zavod Matice hrvatske, Zagreb: Školska knjiga. ISBN 86-401-0058-6