Crocodylus thorbjarnarsoni

Crocodylus thorbjarnarsoni is an extinct species of crocodile from the Pliocene and Pleistocene of the Turkana Basin in Kenya. It is closely related to the species Crocodylus anthropophagus, which lived during the same time in Tanzania. C. thorbjarnarsoni could be the largest known true crocodile,[a] with the largest skull found indicating a possible total length up to 7.6 m (25 ft).[1] It may have been a predator of early hominins. Crocodylus thorbjarnarsoni was named by Christopher Brochu and Glenn Storrs in 2012 in honor of John Thorbjarnarson, a conservationist who worked to protect endangered crocodilians.

| Crocodylus thorbjarnarsoni | |

|---|---|

| |

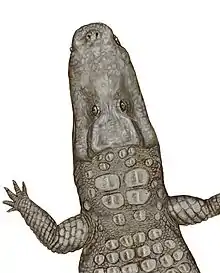

| Life restoration of Crocodylus thorbjarnarsoni | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Crocodilia |

| Family: | Crocodylidae |

| Genus: | Crocodylus |

| Species: | C. thorbjarnarsoni |

| Binomial name | |

| Crocodylus thorbjarnarsoni Brochu & Storrs, 2012 | |

Description

Crocodylus thorbjarnarsoni is distinguished from other crocodiles by its broad snout. It has small raised rims on the prefrontal bones in front of the eyes, a feature also seen in some Nile crocodile individuals. The squamosal bones form raised rims along the sides of the skull table, similar to the crests in C. anthropophagus but much smaller. Also like C. anthropophagus, it has nostrils that open slightly forward rather than directly upward.[1]

The largest C. thorbjarnarsoni skull found (KNM-ER 1682) measures 85 cm (33 in) from the tip of the snout to the back of the skull table, in comparison, the largest known extant Crocodylus skull is that of a saltwater crocodile, measuring 76 cm (30 in). Based on regression analysis for Crocodylus, this corresponds to a total length of 6.2–6.5 m (20–21 ft) but such analysis have been shown to underestimate the size of very large individuals by as much as 20%, which means it could have been as long as 7.6 m (25 ft).[1]

Paleoecology

Crocodylus thorbjarnarsoni likely preyed on human ancestors like Paranthropus and early members of the genus Homo, both of which are known from the Turkana Basin. Direct evidence of crocodilian predation is known from bite marks on hominin bones from the Olduvai Gorge, and these marks were likely made by the closely related crocodile C. anthropophagus (anthropophagus means "human eater" in Greek). No hominin bones from the Turkana Basin bear crocodilian bite marks, so there is no direct evidence that C. thorbjarnarsoni preyed on hominins. However, modern Nile crocodiles are known to consume adult humans, and since C. thorbjarnarsoni was larger than any Nile crocodile, it easily could have eaten smaller-bodied human ancestors. Brochu and Storrs hypothesized that the lack of bite marks could have been due to hominin's awareness of crocodiles and ability to evade them, explaining that "this conflict—eat and drink, but maybe die—was presumably foremost amongst the concerns our predecessors felt when approaching ancient waterways inhabited by Crocodylus thorbjarnarsoni."[1] Another explanation was that C. thorbjarnarsoni may have eaten hominins whole with little need for biting, since it was much larger.[1]

Specimens

Crocodylus thorbjarnarsoni is known from nine skulls, all of which are housed in the National Museum of Kenya. The holotype is a nearly complete skull and lower jaw called KNM-ER 1683 and comes from the approximately 2-million-year-old Koobi Fora Formation on the eastern shore of Lake Turkana. The skulls KNM-ER 1681 and KNM-ER 1682 have also been found from the formation. Three other skulls are known from the Nachukui Formation, west of the holotype's locality. KNM-WT 38977 is from the 2.5- to 3.4-million-year-old Lower Lomekwi Member, KNM-LT 26305 is from the 3.9-million-year-old Kaiyumung Member, and KNM-LT 421 is from the 4.2- to 5.0-million-year-old Apak Member. Three additional skulls called KNM-KP 18338, KNM-KP 30604, and KNM-KP 30619 are known from the southern Turkana Basin in the Kanapoi Formation, dating between 4.07 and 4.12 million years. KNM-ER 1682, KNM-LT 421, KNM-LT 26305, and KNM-KP 30619 were previously assigned to Rimasuchus lloydi, and their reassignment to C. thorbjarnarsoni reduces the range of R. lloydi to Northern Africa.[1]

Phylogeny

Below is a cladogram from Brochu and Storrs's 2012 phylogenetic analysis:[1]

| Crocodylidae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ^ True crocodiles are members of the genus Crocodylus. A broader definition of crocodiles includes all members of the family Crocodylidae.

References

- Brochu, C. A.; Storrs, G. W. (2012). "A giant crocodile from the Plio-Pleistocene of Kenya, the phylogenetic relationships of Neogene African crocodylines, and the antiquity of Crocodylus in Africa". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (3): 587. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.652324.