Mourasuchus

Mourasuchus is an extinct genus of giant, aberrant caiman from the Miocene of South America. Its skull has been described as duck like, being broad, flat and very elongate, closely resembling what is seen in Stomatosuchus, an unrelated crocodylian that may also have had a large gular sac similar to those of pelicans or baleen whales.[1] Mourasuchus, is a strange nettosuchid with an unusually long, broad snout.[2]

| Mourasuchus | |

|---|---|

| |

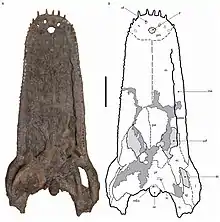

| Skull of Mourasuchus pattersoni | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Crocodilia |

| Family: | Alligatoridae |

| Subfamily: | Caimaninae |

| Genus: | †Mourasuchus Price 1964 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Family-level:

Genus-level:

| |

The synonym Carandaisuchus was used to describe fossils from the Ituzaingó Formation in Argentina demonstrating a pronounced bony occipital crest.[3]

Description

Mourasuchus had rows of small, conical teeth numbering around 40 on each side of the upper and lower jaws.[4] Mourasuchus presumably obtained its food by filter feeding; the jaws were too gracile for the animal to have captured larger prey. It also probed the bottoms of lakes and rivers for food. Fossils have been found in the Pebas Formation at the Fitzcarrald Arch of Peru, where it coexisted with many other crocodylians, including the giant gharial, Gryposuchus, and the alligatorid Purussaurus, both of which were around 11 metres (36 ft) long. The great diversity of crocodylomorphs in this Miocene-age (Tortonian stage, 8 million years ago) wetland suggests that niche partitioning was efficient, which would have limited interspecific competition.[5]

Species

The type species of Mourasuchus is M. amazonensis, named in 1964 based on fossils found in the Solimões Formation of Amazonian Brazil.[6] Another species, M. atopus, was named based on fossils from the Honda Group at the Lagerstätte of La Venta in Colombia, after having been initially assigned to its own genus, Nettosuchus, a year later in 1965.[7][4] The latter species has a longer and narrower skull than the type species. A third species, N. nativus, was named in 1985 based on fossils of the Urumaco Formation of Venezuela,[8] but it was considered a junior synonym of M. arendsi, found in the Ituzaingó Formation of Argentina, by Scheyer & Delfino (2016).[9] A fourth species, M. pattersoni, was described by Cidade et al. (2017).[10] Indeterminate Mourasuchus fossils were found in the Yecua Formation of Bolivia.[11]

References

- Brochu, C. A. (1999). "Phylogenetics, Taxonomy, and Historical Biogeography of Alligatoroidea". Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoir. 6: 9–100. doi:10.2307/3889340. JSTOR 3889340.

- Villanueva, J. B.; Souza Filho, J. P. (1990). "O crocodiliano sul-americano Carandaisuchus como sinonímia de Mourasuchus (Nettosuchidae)". Revista Brasileira de Geociências. 20: 230–233. doi:10.25249/0375-7536.1990230233.

- Langston (2008). "Notes on a partial skeleton of Mourasuchus (Crocodylia, Nettosuchidae) from the Upper Miocene of Venezuela". Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro. 66 (1): 125–143.

- Langston, W. (1966). "Mourasuchus Price, Nettosuchus Langston, and the family Nettosuchidae (Reptilia: Crocodilia)". Copeia. 1966 (4): 882–885. doi:10.2307/1441424. JSTOR 1441424.

- Salas Gismondi et al., 2007, p.357

- Price, L. I. (1964). "Sôbre o crânio de um grande crocodilídeo extinto do alto Rio Juruá, Estado do Acre". An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 36 (1): 59–66.

- Langston, W. (1965). Fossil crocodilians from Colombia and the Cenozoic history of the Crocodilia in South America. University of California Publications in Geological Sciences 52. University of California Press. pp. 1-152.

- Gasparini, Z. B. (1985). "Un nuevo cocodrilo (Eusuchia) Cenozoico de América del Sur". Coletânea de Trabalhos Paleontológicos do IIX Congresso Brasileiro de Paleontologia, MME-DNPM. 27: 51–53.

- Scheyer & Delfino, 2016, p.56

- Cidade et al., 2017, p.9

- Tineo et al., 2015, p.4

Bibliography

- Cidade, G.M.; A. Solórzano; A.D. Rincón; D. Riff, and A.S. Hsiou. 2017. A new Mourasuchus (Alligatoroidea, Caimaninae) from the late Miocene of Venezuela, the phylogeny of Caimaninae and considerations on the feeding habits of Mourasuchus. PeerJ 5. 1–37. Accessed 2018-10-09.

- Salas Gismondi, R.; P.O. Antoine; P. Baby; S. Brusset; M. Benammi; N. Espurt; D. de Franceschi; F. Pujos, and J. Tejada and M. Urbina. 2007. Middle Miocene crocodiles from the Fitzcarrald Arch, Amazonian Peru In: Díaz-Martínez, E. and Rábano, I. (eds.), 4th European Meeting on the Palaeontology and Stratigraphy of Latin America. Cuadernos del Museo Geominero, Instituto Geológico y Minero de España 8. . Accessed 2018-10-09.

- Scheyer, T.M., and M. Delfino. 2016. The late Miocene caimanine fauna (Crocodylia: Alligatoroidea) of the Urumaco Formation, Venezuela. Palaeontologia Electronica 19. 1–57. Accessed 2018-10-09.

- Tineo, D.E.; P. Bona; L.M. Pérez; G.D. Vergani; G. González; D.G. Poiré; Z. Gasparini, and P. Legarreta. 2015. Palaeoenvironmental implications of the giant crocodylian Mourasuchus (Alligatoridae, Caimaninae) in the Yecua Formation (late Miocene) of Bolivia. Alcheringa 39. 1–12. Accessed 2018-10-09.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mourasuchus. |

.jpg.webp)