Eastern Settlement

The Eastern Settlement (Old Norse: Eystribygð) was the first and by far the largest of the two main areas of Norse Greenland, settled c. AD 985-1000 by Norsemen from Iceland. At its peak, it contained approximately 4,000 inhabitants. The last written record from the Eastern Settlement is of an Icelandic/Greenlandic wedding in Hvalsey in 1408, placing it about 50–100 years later than the end of the more northern Western Settlement.[1]

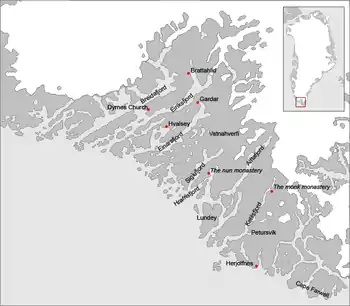

Despite its name, the Eastern Settlement was more south than east of its companion and, like the Western Settlement, was located on the southwestern tip of Greenland at the head of long fjords such as Tunulliarfik Fjord or Eiriksfjord, Igaliku or Einarsfjord, and Sermilik Fjord (see map at right). Approximately 500 groups of ruins of Norse farms are found in the area, including 16 church ruins, including Brattahlíð, Dyrnæs, Garðar, Hvalsey and Herjolfsnes.[2] The Vatnahverfi district to the southeast of Einarsfjord had some of the best pastoral land in the colony, and boasted 10% of all the known farm sites in the Eastern Settlement.

The economy of the medieval Norse settlements was based on livestock farming – mainly sheep and cattle, with significant supplement from seal hunting. A climate deterioration in the 14th century may have increased the demand for winter fodder and at the same time decreased productivity of hay meadows. Isotope analysis of bones excavated at archaeological investigations in the Norse settlements has found that fishing played an increasing economic role towards the end of the settlement's life. While the diet of the first settlers consisted of 80% agricultural products and 20% marine food, from the 14th century the Greenland Norsemen had 50–80% of their diet from the sea.[3][4]

In the Greenlandic Inuit tradition, there is a legend about Hvalsey. According to this legend, there was open war between the Norse chief Ungortoq and the Inuit leader K'aissape. The Inuit made a massive attack on Hvalsey and burned down the Norse inside their houses, but Ungortoq escaped with his family. K'aissape conquered him after a long pursuit, which ended near Cape Farewell. However, according to archaeological studies, there is no sign of a conflagration. Other explanations have also been offered including soil erosion due to overgrazing and the effects of the Black Death.[5][6]

See also

- History of Greenland

- Norse colonization of the Americas

- Western Settlement

- Ivittuut, the scene of a smaller "Middle Settlement"

- Danish colonization of the Americas

References

- Dale Mackenzie Brown (February 28, 2000). "The Fate of Greenland's Vikings". Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- Kathy A. Svitil (July 1, 1997). "The Greenland Viking Mystery". Discover Magazine. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- Arneborg, Jette; Heinemeier, Jan; Lynnerup, Niels; Nielsen, Henrik L.; Rud, Niels; Sveinbjörnsdóttir, Árný E. (1999). "Change of diet of the Greenland vikings determined from stable carbon isotope analysis and 14C dating of their bones" (PDF). Radiocarbon. 41 (2): 157–168.

- Andrew J. Dugmore; et al. "Norse Greenland settlement and limits to adaptation" (PDF). North Atlantic Biocultural Organization cooperative. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-07. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- Magnús Sveinn Helgason (December 18, 2015). "What happened to the Viking settlement of Greenland? New research shows cooling weather not a factor". Iceland Magazine. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- Andrew J. Dugmore; et al. (December 23, 2011). "Cultural adaptation, compounding vulnerabilities and conjunctures in Norse Greenland". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. vol. 109 no. 10. Retrieved January 20, 2016.