Ehrlichia chaffeensis

Ehrlichia chaffeensis is an obligate intracellular,[1] Gram-negative species of Rickettsiales bacteria.[2] It is a zoonotic pathogen transmitted to humans by the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum).[3] It is the causative agent of human monocytic ehrlichiosis.[4]

| Ehrlichia chaffeensis | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | Alphaproteobacteria |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | E. chaffeensis |

Genetic studies support the endosymbiotic theory that a subset of these organisms evolved to live inside mammalian cells as mitochondria to provide cellular energy to the cells in return for protection and sustenance. ATP production in the rickettsiae is biochemically identical to that in mammalian mitochondria; all multi-cellular eukaryotes have mitochondria in their cells, including birds, fish, reptiles, invertebrates, plants, and fungi in addition to mammals.

Human monocytic ehrlichiosis caused by E. chaffeensis is known to spread through tick infection primarily in the Southern, South-central and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.[5] In recent years, the lone star tick has expanded its range along the East Coast to New England, putting more humans at risk for tick-borne infections.[6]

It is named for Fort Chaffee, where the bacterium was first discovered in blood samples of infected patients.[2]

Transmission cycle

E. chaffeensis is maintained in nature through a complex zoonotic relationship. The white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) is known to be the main competent reservoir for E. chaffeensis[1] and the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) is the principal vector for human transmission.[3] Some evidence shows that other organisms may serve as reservoirs for the bacteria such as domestic goats, domestic dogs, raccoons,[1] and coyotes.[5]

E. chaffeensis can be transmitted to uninfected tick larvae when feeding on the blood from an infected host.[7] The infection is then maintained and can be transmitted to a reservoir organism or humans at the nymphal stage. Adult ticks can maintain the infection or be infected from feeding on the blood of an infected reservoir organism and may also pass E. chaffeensis to humans or other uninfected reservoir organisms.[1] Transovarial transmission is not known to occur, so eggs and unfed larvae are not believed to be infected.[7]

Pathogenesis

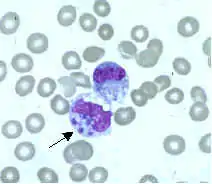

E. chaffeensis causes human monocytic ehrlichiosis and is known to infect monocytes.[1] It has also been known to infect other cell types such as lymphocytes, atypical lymphocytes, myelocytes, and neutrophils, but monocytes appear to best harbor the infection.[1]

E. chaffeensis has also been shown to infect canines both naturally[6] and artificially.[8] Symptoms in canine infections are hard to differentiate between E. chaffeensis infection and E. canis, which is the species of Ehrlichia that most commonly affects canines.[8]

Signs and symptoms

Patients display early symptoms within 1 to 2 weeks after tick infection. Early symptoms include fever, headache,[9] malaise, low-back pain, or gastrointestinal symptoms.[3] Some patients may also have myalgias or arthralgias, and an estimated 10–40% of patients may develop coughing, pharyngitis, diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and changes in mental status.[1]

Diagnosis or detection

A variety of procedures have been used to detect E. chaffeensis in humans and reservoir organisms. Most commonly, serologic testing and PCR amplification are used.[1][3]

Treatment

E. chaffeensis is susceptible to tetracyclines.[1] Doxycycline treatment is suggested for any patients presenting symptoms of an Ehrlichia infection during the appropriate season and potential tick exposure.[9]

See also

References

- Ganguly, S (2008). "Tick-borne ehrlichiosis infection in human beings" (PDF). Journal of Vector Borne Diseases. 45 (4): 273–280.

- Ehrlichia+chaffeensis at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Allan, B. F. (2012). "Blood meal analysis to identify reservoir hosts for amblyomma americanum ticks". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 16 (3): 433–440. doi:10.3201/eid1603.090911. PMC 3322017. PMID 20202418.

- Schutze GE, Buckingham SC, Marshall GS, et al. (June 2007). "Human monocytic ehrlichiosis in children". Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 26 (6): 475–9. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e318042b66c. PMID 17529862.

- Barker, R. W. (2000). "Naturally occurring ehrlichia chaffeensis infection in coyotes from oklahoma". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 6 (5): 477–80. doi:10.3201/eid0605.000505. PMC 2627953. PMID 10998377.

- Little, S. E. (2007, January). New developments in managing vector-borne diseases. Retrieved from http://www.iknowledgenow.com/tocnavc2007smallanimal.cfm

- Long, S. W. (2003). "Evaluation of transovarial transmission and transmissibility of Ehrlichia chaffeensis (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae) in Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae)". Journal of Medical Entomology. 40 (6): 1000–1004. doi:10.1603/0022-2585-40.6.1000. PMID 14765684.

- Baneth, G. (2010). Ehrlichia and anaplasma infections. Paper presented at World small animal veterinary congress. Retrieved from http://www.ivis.org/proceedings/wsava/2010/d12.pdf

- Baddour, L. M. (2011). Newly discovered ehrlichia species implicated in human infection. Journal Watch Infectious Diseases