Eodicynodon

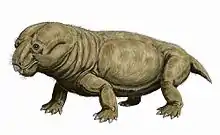

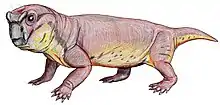

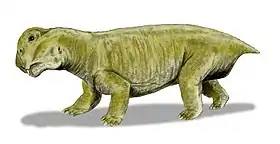

Eodicynodon (eo-, early or primitive, dicynodont) is an extinct genus of dicynodont therapsids, a highly diverse group of herbivorous synapsids that were widespread during the middle-late Permian and early Triassic. As its name suggests, Eodicynodon is the oldest and most primitive dicynodont yet identified, ranging from the middle to late Permian and possessing a mix of ancestral Anomodont/therapsid features and derived dicynodont synapomorphies.

| Eodicynodon | |

|---|---|

| |

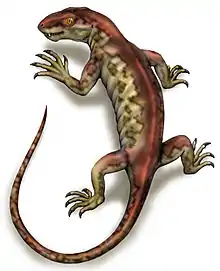

| Restoration of Eodicynodon oosthuizeni | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Clade: | †Dicynodontia |

| Family: | †Eodicynodontidae Barry, 1974 |

| Genus: | †Eodicynodon Barry, 1974 |

| Type species | |

| †E. oosthuizeni Barry, 1974 | |

First described by paleontologist T. H. Barry in 1974, its only associated species, E. oosthuizeni, is named after Roy Oosthuizeni, the South African farmer who discovered the type specimen (a partial skull without the mandible) on his Cape Province farm between 1964 and 1970.[1]

Description

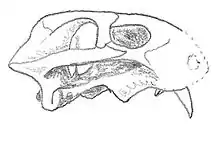

Eodicynodon was a medium-sized dicynodont, at about 450 mm long and 150 mm high.[2] While it had many features common to all dicynodonts, such as canine tusks and jaw structures related to the "cheek pivot system" of mastication, it also displayed a number of ancestral features more similar to some of its primitive therapsid relatives,[2][3][1][4] which are listed below.

Palate/snout

While the premaxillary bones are fused in more derived dicynodonts, a thin suture extending dorsally up from the palatal facet reveals that they are paired in Eodicynodon, an ancestral feature they share with their primitive relatives Venyukovia, Otsheria, and Pelycosauria.[1]

Similarly, while the vomers of later dicynodonts are fused, they are paired in Eodicynodon and together with the pterygoid border the intervomero-pterygoidal vacuity; in more derived dicynodonts, this vacuity is more posteriorly located and exclusively bordered by the pterygoid. These features are also present in more primitive relatives of dicynodonts, including Pristerodon,[5] sphenacodont pelycosaurs, cotylosaurs, and Venyukovia.[6][1]

Mastication

Dicynodonts were specialized herbivores that employed a unique “cheek pivot system” of mastication that created powerful shearing action upon closure of the jaw and subsequently ground mouth contents through a system of interlocking ridges and grooves formed from the palate and dentary.[3]

Two morphological features, present already in Eodicynodon, made this motion possible. The first was a double convex jaw joint, wherein both the quadrate and articular formed convex condyles. As the jaw closed, the articular condyle of the lower jaw slid anterio-dorsally along the quadrate condyle, resulting in closure of the mouth from back to front as the posterior end of the mandible was elevated dorsally relative to the anterior end. Forward slide of the lower jaw was limited by the second morphological feature unique to dicynodonts, a pivot point created between the dentary groove and palatal notch upon closure of the jaw. The lower jaw would then move so that the articular condyle slid anterio-ventrally along the quadrate condyle, which would cause the mandible to pivot in such a way that the front of the mouth closed and the back opened.[3]

Discovery and geology

The South African Karoo Supergroup is a fossil-rich series of bedded shales that was continuously deposited beginning in the late Carboniferous through the early Jurassic. Though a diverse assemblage of dicynodonts appears early on in the Beaufort Group, the immediately preceding Ecca was long understood to be barren of fossils, despite a lack of geological evidence for a change in paleoenvironment from Ecca to Beaufort. From 1964 to 1970, the farmer Roy Oosthuizen, whose land was located in an area firmly established as Upper Ecca (Middle Permian), collected a number of nodules containing the remains of several therapsids, including several small dicynodonts and the partial skull that is the type specimen of Eodicynodon.[1]

Classification

Synapsida

| Synapsida |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dicynodontia

Below is a cladogram modified from Angielczyk and Rubidge (2010) showing the phylogenetic relationships of Dicynodontia:[8]

| Dicynodontia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- Barry, T.H. (1974). "A NEW DICYNODONT ANCESTOR FROM THE UPPER ECCA LOWER MIDDLE PERMIAN OF SOUTH AFRICA". Annals of the South African Museum. 64: 117–136 – via BioStor.

- Rubidge, B.S.; King, G.M. & Hancox, P.J. (1994). "The Postcranial Skeleton of the Earliest Dicynodont Synapsid Eodicynodon from the Upper Permian of South Africa" (PDF). Palaeontology. 37: 397–408.

- Cox, C. Barry (1998). "The jaw function and adaptive radiation of the dicynodont mammal-like reptiles of the Karoo basin of South Africa". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 122 (1–2): 349–384. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1998.tb02534.x.

- Abdala, Fernando; Rubidge, Bruce S.; Van Den HEEVER, Juri (2008-07-01). "The Oldest Therocephalians (therapsida, Eutheriodontia) and the Early Diversification of Therapsida". Palaeontology. 51 (4): 1011–1024. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00784.x. ISSN 1475-4983.

- Barry, T. H. (1967). "The cranial morphology of the Permo-Triassic anomodont Pristerodon buffaloensis with special reference to the neural endocranium and visceral arch section". Annals of the South African Museum. 50: 131–161.

- Efremov, J. A. (1940). "Preliminary description of the new Permian and Triassic Tertrapoda from USSR". Trudy Paleont. Inst. 10: 1–140.

- Modesto, S. P.; Rubidge, B.; Visser, I. & Welman, J. (2003). "A new basal dicynodont from the Upper Permian of South Africa". Palaeontology. 46: 211–223. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00295.

- Kenneth D. Angielczyk; Bruce S. Rubidge (2010). "A new pylaecephalid dicynodont (Therapsida, Anomodontia) from the Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone, Karoo Basin, Middle Permian of South Africa". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (5): 1396–1409. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.501447.

Sources

- The Origin and Evolution of Mammals (Oxford Biology) by T. S. Kemp