Equidae

Equidae (sometimes known as the horse family) is the taxonomic family of horses and related animals, including the extant horses, donkeys, and zebras, and many other species known only from fossils. All extant species are in the genus Equus, which originated in North America. Equidae belongs to the order Perissodactyla, which includes the extant tapirs and rhinoceros, and several extinct families.

| Equidae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Wild horses | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Suborder: | Hippomorpha |

| Family: | Equidae Gray, 1821 |

| Extant and subfossil genera | |

|

For fossil genera and classification see text | |

The term equid refers to any member of this family, including any equine.

Evolution

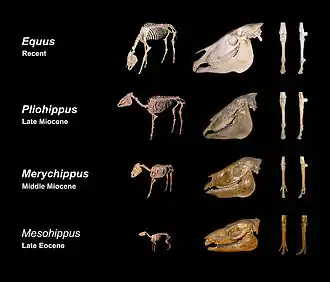

The oldest known fossils assigned to Equidae were found in North America, and date from the early Eocene, 54 million years ago. They used to be assigned to the genus Hyracotherium, but the type species of that genus now is regarded to be not a member of this family. The other species have been split off into different genera. These early equids were fox-sized animals with three toes on the hind feet, and four on the front feet. They were herbivorous browsers on relatively soft plants, and already adapted for running. The complexity of their brains suggest that they already were alert and intelligent animals.[1] Later species reduced the number of toes, and developed teeth more suited for grinding up grasses and other tough plant food.

The equids, like other perissodactyls, are hindgut fermenters. They have evolved specialized teeth that cut and shear tough plant matter to accommodate their fibrous diet.[2] Their seemingly inefficient digestion strategy is a result of their size at the time of its evolution,[3] as they would have already had to be relatively large mammals to be supported on such a strategy.

The family became relatively diverse during the Miocene, with many new species appearing. By this time, equids were more truly horse-like, having developed the typical body shape of the modern animals.[4] Many of these species bore the main weight of their bodies on their central, third, toe, with the others becoming reduced, and barely touching the ground, if at all. The sole surviving genus, Equus, had evolved by the early Pleistocene, and spread rapidly through the world.[5]

Classification

- Order Perissodactyla (In addition to Equidae, Perissodactyla includes four species of tapir in a single genus, as well as five living species (belonging to four genera) of rhinoceros.) † indicates extinct taxa.

- Family Equidae

- Genus †Epihippus

- Genus †Haplohippus

- Genus †Eohippus

- Genus †Minippus[6]

- Genus †Orohippus

- Genus †Pliolophus

- Genus †Protorohippus

- Genus †Sifrhippus

- Genus †Xenicohippus[6]

- Genus †Eurohippus

- Genus †Propalaeotherium

- Subfamily †Anchitheriinae

- Genus †Anchitherium

- Genus †Archaeohippus

- Genus †Desmatippus

- Genus †Hypohippus

- Genus †Kalobatippus

- Genus †Megahippus

- Genus †Mesohippus

- Genus †Miohippus

- Genus †Parahippus

- Genus †Sinohippus

- Subfamily Equinae

- Genus †Merychippus

- Genus †Scaphohippus

- Genus †Acritohippus

- Tribe †Hipparionini

- Genus †Eurygnathohippus

- Genus †Hipparion

- Genus †Hippotherium

- Genus †Nannippus

- Genus †Neohipparion

- Genus †Proboscidipparion

- Genus †Pseudhipparion

- Tribe Equini

- Genus †Haringtonhippus[7]

- Genus †Heteropliohippus[8]

- Genus †Parapliohippus[8]

- Subtribe Protohippina

- Genus †Calippus

- Genus †Protohippus

- Subtribe Equina

- Genus †Astrohippus

- Genus †Dinohippus

- Genus Equus (22 species, 7 extant)

- Genus †Hippidion

- Genus †Onohippidium

- Genus †Pliohippus

- Family Equidae

References

- Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 255. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- Engels, Sandra; Schultz, Julia A. (June 2019). "Evolution of the power stroke in early Equoidea (Perissodactyla, Mammalia)". Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments. 99 (2): 271–291. doi:10.1007/s12549-018-0341-4. ISSN 1867-1594. S2CID 133808650.

- Janis, Christine (1976). "The Evolutionary Strategy of the Equidae and the Origins of Rumen and Cecal Digestion". Evolution. 30 (4): 757–774. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1976.tb00957.x. ISSN 1558-5646. PMID 28563331. S2CID 5053639.

- MacFadden, B. J. (March 18, 2005). "Fossil Horses--Evidence for Evolution". Science. 307 (5716): 1728–1730. doi:10.1126/science.1105458. PMID 15774746. S2CID 19876380.

- Savage, RJG & Long, MR (1986). Mammal Evolution: an illustrated guide. New York: Facts on File. pp. 200–204. ISBN 0-8160-1194-X.

- Froehlich, D.J. (February 2002). "Quo vadis eohippus? The systematics and taxonomy of the early Eocene equids (Perissodactyla)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 134 (2): 141–256. doi:10.1046/j.1096-3642.2002.00005.x.

- Hay, Oliver P. (1915). "Contributions to the Knowledge of the Mammals of the Pleistocene of North America". Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 48 (2086): 535–549. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.48-2086.515

- Bravo-Cuevas, V.M.; Ferrusquía-Villafranca, I. (2010). "The oldest record of Equini (Mammalia: Equidae) from Mexico" (PDF). Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas. 27 (3): 593–603. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

| Look up Equidae or equid in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |