Everton Weekes

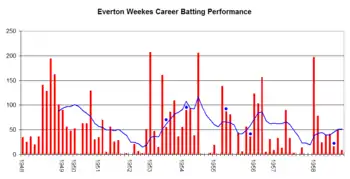

Sir Everton DeCourcy Weekes, KCMG, GCM, OBE (26 February 1925 – 1 July 2020)[1] was a cricketer from Barbados. A right-handed batsman, he was known as one of the hardest hitters in world cricket. Along with Frank Worrell and Clyde Walcott, he formed what was known as "The Three Ws" of the West Indies cricket team.[2] Weekes played in 48 Test matches for the West Indies cricket team from 1948 to 1958. He continued to play first-class cricket until 1964, surpassing 12,000 first-class runs in his final innings. As a coach he was in charge of the Canadian team at the 1979 Cricket World Cup, and he was also a commentator and international match referee.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Everton DeCourcy Weekes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 26 February 1925 Saint Michael, Barbados | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 1 July 2020 (aged 95) Christ Church, Barbados | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Batting | Right-handed | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bowling | Right-arm leg break | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Role | Occasional wicket-keeper | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relations | David Murray (son) Ken Weekes (cousin) Ricky Hoyte (grandson) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National side | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Test debut (cap 59) | 21 January 1948 v England | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Test | 31 March 1958 v Pakistan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domestic team information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years | Team | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1944–1964 | Barbados | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Career statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: ESPN Cricinfo, 1 July 2020 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Youth and early career

Born in a wooden shack on Pickwick Gap in Westbury, Saint Michael, Barbados, near Kensington Oval, Weekes was named by his father after English football team Everton (when Weekes told English cricketer Jim Laker this, Laker reportedly replied "It was a good thing your father wasn't a West Bromwich Albion fan.")[3] Weekes was unaware of the source of DeCourcy, his middle name, although he believed there was a French influence in his family.[3]

Weekes's family was poor and his father was forced to leave his family to work in the Trinidad oilfields when Weekes was eight. He did not return to Barbados for eleven years.[4] In the absence of his father, Weekes and his sister were raised by his mother Lenore and an aunt, whom Weekes credits with his successful upbringing.[4] Weekes attended St Leonard's Boys' School, where he later bragged that he never passed an exam (although he would later successfully study Hotel Management)[5] and preferred to concentrate on sport.[6] In addition to cricket, Weekes was also a keen football player, representing Barbados.[7] As a boy Weekes assisted the groundsmen at Kensington Oval and often acted as a substitute fielder[8] in exchange for free entry to the cricket, giving himself the opportunity to watch leading international cricketers at close range.[9] At age 13 Weekes began playing for Westshire Cricket Club in the Barbados Cricket League (BCL). He would have preferred to have played for his local club, Pickwick, but the club only catered to white players.[10]

Weekes left school in 1939, aged 14, and, not having a job, spent his days playing cricket and football. He later attributed much of his cricketing success to this time spent practising.[11] In 1943 Weekes enlisted in the Barbados Regiment and served as a lance corporal[10] until his discharge in 1947 and while he never saw active service,[9] the fact he was in the military meant he was eligible to play cricket for Garrison Sports Club in the higher standard Barbados Cricket Association in addition to Westshire in the BCL.[10]

Early first-class career

Weekes's performances in Barbados club cricket led to his selection in a 1945 trial match to select a first-class side to represent Barbados on a Goodwill tour of Trinidad and Tobago. Weekes scored 88 and 117 retired and was selected for the tour,[6] making his first-class debut on 24 February 1945, aged 19 years, 364 days, for Barbados against Trinidad and Tobago at Queen's Park Oval, Port of Spain. Batting at number six, he scored 0 and eight as Barbados lost by ten wickets.[12]

Weekes scored his maiden first-class half century in his next match, making 53 as an opener against Trinidad in March 1945 (where he also bowled for the first time in a first class match, conceding 15 runs in four wicketless overs).[13] In his first two first-class seasons Weekes was only a moderate success with the bat, averaging 16.62 by the end of the 1945/46 season[6] but began to find form in 1946/47, when, batting at number four, his maiden first-class century, 126 against British Guiana at Bourda, Georgetown,[14] and averaged 67.57 for the season.[6] The 1947/48 season included a tour by MCC and Weekes impressed West Indian selectors with an unbeaten 118 against the tourists prior to the first Test in Bridgetown.[6]

The Three Ws

Weekes was one of the "Three Ws", along with Clyde Walcott and Frank Worrell, noted as outstanding batsmen from Barbados who all made their Test debut in 1948 against England. The three were all born within seventeen months of each other and within a mile of Kensington Oval in Barbados[15] and Walcott believed that the same midwife delivered each of them.[16] Weekes first met Walcott in 1941, aged 16, when they were team mates in a trial match.[17] They shared a room together when on tour[17] and, along with Worrell, would go dancing together on Saturday nights after playing cricket.[18]

The name "Three Ws" was coined by an English journalist during the 1950 West Indian tour of England.[19] Walcott believed that Weekes was the best all-round batsman of the three, while Worrell was the best all-rounder and modestly referred to himself as the best wicket keeper of the trio.[20] After their retirement from cricket, the three remained close and, following the death of Worrell in 1967, Weekes acted as one of the pallbearers at his funeral.[21] The 3Ws Oval, situated on the Cave Hill campus of the University of the West Indies was named in their honour, and a monument to the three Ws is opposite the oval.[22] Worrell and Walcott are buried on ground overlooking the oval.[23]

Test career

| Don Bradman (AUS) | 99.94 |

| Adam Voges (AUS) | 61.87 |

| Graeme Pollock (RSA) | 60.97 |

| George Headley (WI) | 60.83 |

| Herbert Sutcliffe (ENG) | 60.73 |

| Eddie Paynter (ENG) | 59.23 |

| Ken Barrington (ENG) | 58.67 |

| Everton Weekes (WI) | 58.61 |

| Wally Hammond (ENG) | 58.45 |

| Garfield Sobers (WI) | 57.78 |

Source: Cricinfo Qualification: 20 completed innings, career completed. | |

Weekes made his Test debut for the West Indies against England at Kensington Oval on 21 January 1948, aged 22 years and 329 days. He was one of 12 debutants; seven from the West Indies (the others were Walcott, Robert Christiani, Wilfred Ferguson, Berkeley Gaskin, John Goddard and Prior Jones) and five for England; Jim Laker, Maurice Tremlett, Dennis Brookes, Winston Place and Gerald Smithson. Batting at number three, Weekes made 35 and 25 as the match ended in a draw.[24]

Weekes's performance in his next two Tests, in the words of Wisden, "did little to indicate the remarkable feats which lay ahead"[25] and was initially dropped from the Fourth and final Test of the series against England before an injury to George Headley allowed Weekes to return to the side.[26] After being dropped on 0, Weekes scored 141, his maiden Test century[27] and was subsequently chosen for the West Indies tour of India, Pakistan and Ceylon.

In his next Test, the First against India, at Delhi, in November 1948 (the first by West Indies in India),[27] Weekes scored 128, followed by 194 in the Second Test in Bombay and 162 and 101 in the Third Test in Calcutta. Weekes then made 90 in the Fourth Test in Madras, being controversially run out[27] and 56 and 48 in the Fifth Test at Bombay. Weekes's five Test centuries in consecutive innings is a Test record, passing the record previously held by Jack Fingleton and Alan Melville[28] as was his achievement of seven Test half-centuries in consecutive innings,[27] passing the record previously jointly held by Jack Ryder, Patsy Hendren, George Headley and Melville.[29] (Andy Flower and Shivnarine Chanderpaul have since equaled Weekes' record of seven half centuries).[30]

By the end of the series, which also included a century against Ceylon, at that time a non-Test cricketing nation, and a half-century against Pakistan in a match not classed as a Test match, Weekes had a Test batting average of 82.46 and had passed 1,000 Test runs in his twelfth innings, one fewer than Donald Bradman.[31] Early in the tour the West Indian team's cricket kit disappeared and Weekes was surprised to see Indian fishermen wearing flannels and West Indian cricket jumpers.[32] As a result of his series, Weekes was named one of the 1949 Indian Cricket "Cricketers of the Year".[33] The next season saw no Test cricket played by West Indies but Weekes scored 236* against British Guiana at Bridgetown, averaged 219.50 for the season and raised his career first-class average to 72.64.[34]

West Indies in England 1950

In 1950 West Indies toured England and Weekes continued his excellent form, scoring 338 runs at 56.33 and playing a significant part in the West Indies 3–1 victory in the Test series, as well as 2310 first-class runs at 79.65 (including five double centuries, a record for a West Indian tour of England).[35] By the end of the series, Weekes had scored 1,410 Test runs at 74.21 and had enhanced his reputation as one of the finest slip fielders in world cricket, taking 11 catches in the series. Additionally, his 304* against University of Cambridge remains the only triple century by a West Indian on tour in England.[35] In recognition of his performance, Weekes was named a 1951 Wisden Cricketer of the Year.[25]

West Indies in Australia and New Zealand 1951/52

Named as a member of the West Indian team to tour Australia in 1951/52, Weekes was troubled by a range of injuries throughout the tour, including an ongoing thigh injury[36] and a badly bruised right thumb when a door slammed shut on it while he was helping an injured Walcott out of his room,[37] subsequently leaving his performances below expectations.

Additionally, as the leading West Indian batsman, Weekes was targeted by the Australian fast bowlers, in particular Ray Lindwall, subjecting him to Bodyline-like tactics of sustained short pitched bowling. Reviewing the series, the Sydney Morning Herald claimed that the Australian tactics to contain Weekes may have been just within the laws of cricket but infringed on the spirit of the game.[38] Leading cricket commentator Alan McGilvray later wrote "I remain convinced to this day the bumpers hurled at Weekes had a definite influence on charging up West Indian competitiveness in future series."[39] Following the Australian tour, the West Indies visited New Zealand. In a tour match against Wellington, Weekes kept wicket in the absence of the injured Simpson Guillen and effected the only stumping of his first class career.[40]

India in the West Indies 1952/53

During the Port of Spain Test against India in February 1953, Weekes surpassed George Headley's record of 2190 as West Indies' highest Test run scorer. Weekes would hold this record until June 1966 when surpassed by Gary Sobers.[41]

Australia in the West Indies 1954/55

Weekes took his sole Test wicket in this series. In the First Test at Sabina Park, Kingston, with Australia requiring just 20 runs in their second innings to win the Test, Weekes opened the bowling and had Arthur Morris caught by Glendon Gibbs.[42] The Australians were surprised at the level of racism evident throughout the West Indies at the time, and were embarrassed to find that Weekes, Worrall and Walcott had not been invited to a cocktail party at the home of a white West Indian player.[43]

Other achievements include three centuries in consecutive innings against New Zealand in 1956, and a partnership of 338 with Worrell against England in 1954, still a West Indian record for the third wicket. In 1954 Weekes was chosen as the first tenured black captain of Barbados and the second black captain overall following Herman Griffith's temporary captaincy in 1941.[44]

West Indies in England 1957

Weekes was affected by sinusitis throughout the tour, requiring five operations,[45] and broke a finger in late June.[46] Reporting on the final day of the 1957 Lord's Test where Weekes had made a rearguard 90 as the West Indies slumped to an innings defeat, The Times's cricket correspondent wrote "It had been a day to quicken one's feeling for cricket, glowing with freshness and impulse and friendliness, and it had belong to Weekes."[47] Denis Compton said of Weekes following this innings; "In every respect, it was the innings of a genius."[48] During the tour Weekes became only the fourth West Indian to pass 10,000 first-class runs.[49] Weekes was the first West Indian to pass 3,000 Test runs, in 31 Test matches, and the first to score 4,000 Test runs, in 42 Tests.

Lancashire League

In 1949 Weekes accepted an offer of £500 to play as the professional for Bacup in the Lancashire League.[50] When he first arrived in Bacup, Weekes was greatly affected by the cold and took to wearing an army great coat everywhere, to the extent it became part of his League image.[51] His homesickness for Barbados was tempered by his landlady's potato pies and the presence of Worrell and Walcott, who were playing for League clubs Radcliffe and Enfield respectively. The three Ws would regularly meet at Weekes's house midweek for an evening of piano playing and jazz singing.[52]

In all, Weekes played seven seasons in the Lancashire League between 1949 and 1958, passing 1000 runs in each.[53] His 1,518 runs scored in 1951 is still the club record and for 40 years was the League record, until broken by Peter Sleep.[54] Weekes scored a total of 9,069 runs for Bacup at 91.61, with 25 centuries, including 195* against Enfield, a score that remains a League record,[51] as does his 1954 batting average of 158.25.[52] Weekes also had success with the ball, taking at least fifty wickets in all but one season at Bacup, including 80 wickets in 1956.[51]

During the 1954 season he also played for neighbouring Central Lancashire League club Walsden as sub professional in the Wood Cup Final. His 150 runs and 9 wickets helped the village club to their first trophy in the seventy years since they became founder members of the CLL. Weekes's performances were a significant contribution to League crowds, with over 325,000 spectators attending Lancashire League matches in 1949, a record as yet unsurpassed.[51] He also played up for the crowds; batting in a match against Rawtenstall Cricket Club, Weekes waited until a ball had passed him before taking his left hand off his bat and hitting the ball around his back through square leg for four.[51]

Style

Weekes had a classic batting style, possessed a variety of shots on both sides of the wicket,[9] and is considered one of the hardest hitters in cricket history.[55] The Times described him as lightly bow-legged, with a wonderful eye, wrists the envy of any batsman, and feet always in the right place to play a shot,[47] and Richie Benaud stated that many Australians who saw Weekes in action said he was the closest batsman in style to the pre-World War II Donald Bradman.[55] He was also compared to Bradman in his ability to keep the scoreboard moving and in using his feet to come down the pitch to slower bowlers.[56] Additionally, Weekes was an excellent fielder, initially in the covers before moving into the slips,[56] and produced a training manual entitled Aspects of Fielding.

Retirement and post-cricketing career

Weekes retired from Test cricket in 1958 due to a persistent thigh injury but continued in first-class cricket until 1964, his final first-class match being against Trinidad and Tobago in Port-of-Spain, scoring 19 and 13.[57] Weekes passed 12,000 first-class runs in his final innings, becoming only the third West Indian, after Worrell and Roy Marshall, to do so.[58]

Post-retirement, Weekes would make occasional appearances in charity and exhibition matches, including for the International Cavaliers.[59] In one 1967 match, aged 42, Weekes, out of practice and in borrowed gear, dominated a bowling attack half his age.[59] Weekes also participated in a Cavaliers tour of Rhodesia in the early 1960s, where he was the focus of racial discrimination, including having a match against a Bulawayo side moved to a substandard ground in a black area due to a local bylaw banning blacks from playing in a white area.[60] Feeling humiliated, Weekes and fellow West Indian Rohan Kanhai threatened to abandon the tour but remained following an apology from Rhodesian government officials.[61]

While Weekes was never coached as a young player, he was appointed a Barbados Government Sports Officer in 1958[62] and found great success as a coach, encouraging young players to obey their instincts and develop their own style.[63] Such was his success, Weekes was appointed coach of the Canadian side at the 1979 Cricket World Cup.[64] Additionally, Weekes served on the executive of the Barbados Cricket Association for many years[65] and helped develop many leading Barbadian players, including Conrad Hunte and Seymour Nurse, both deeply influenced by Weekes.[66] Weekes also found time to work as a television and radio cricket commentator, known for his acerbic wit and deep knowledge of the game[67] and began to play Dominoes and Bridge competitively, representing Barbados in regional Bridge championships.[68] The New York Times referred to his style as "aggressive".[69]

In 1994 Weekes was appointed as an International Cricket Council match referee, refereeing in four Tests and three One Day Internationals.[70] Weekes published his memoirs Mastering the Craft: Ten years of Weekes, 1948 to 1958 in December 2007, when it was announced that the book will be included in the curriculum of the Caribbean Civilisation Foundation course at the University of the West Indies.[71] Outside of cricket, Weekes became a Justice of the Peace and served on a number of Barbados Government bodies, including the Police Service Commission.[72] Weekes' cousin Kenneth Weekes and son David Murray also played Test cricket for the West Indies, while his grandson Ricky Hoyte played first-class cricket for Barbados[73] and his nephew Donald Weekes played one first-class match for Sussex.[74]

In June 2019, Weekes was placed in intensive care, after suffering a heart attack in Barbados.[75] On 1 July 2020, he died at the age of 95 in Christ Church.[76][77]

Honours and legacy

Following the end of his cricketing career, Weekes received a range of distinctions, including being made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE), the Barbados Gold Crown of Merit (GCM) and in 1995 Weekes was made a Knight of the Order of St Michael and St George (KCMG) for his services to cricket.[78] For the 2000 edition of Wisden Cricketers' Almanack, Weekes was asked to be a member of the 100 strong electorate to select the Five Cricketers of the 20th Century. All voters were allowed to nominate five players and while there was no disclosure of which five each voter chose, Wisden editor Matthew Engel revealed that Weekes voted for Dennis Lillee and, as Sir Donald Bradman received 100 votes, it is obvious Weekes voted for Bradman as well.[79]

The former Prime Minister of Barbados Owen Arthur paid tribute to Weekes for his role in bringing social change to Barbados and the Caribbean, stating "Through his excellence on the cricket field, Sir Everton helped in a fundamental way to change Barbados for the better, forever, by proving that true excellence cannot be constrained by social barriers."[80] In addition to the 3Ws Oval, Weekes has been honoured throughout Barbados, including having a roundabout in Warrens, St. Michael named after him.[81] In January 2009 Weekes was one of 55 players inducted into the ICC Cricket Hall of Fame and will choose new inductees to the Hall of Fame.[82]

Weekes had a Test batting average of nearly 97.92 in innings immediately after those in which he scored a hundred, the second highest (after Vijay Hazare) for those who had scored five Test centuries.[83] As of 2 July 2020, Weekes' career Test batting average of 58.61 is the ninth highest of all players with 30 or more innings.[84] An oddity of his career was the first innings bias averaging 71.44 compared with 36.64 in the second, and only one of his fifteen tons came in the second innings.

Records

- Fastest in world to reach 1000 Test runs (shares the record with Herbert Sutcliffe) by achieving the feat in the 12th innings of his career.

Notes

- https://www.thetimes.co.uk/edition/register/sir-everton-weekes-hfncshblx

- "Sir Everton Weekes, the last of the three Ws, dies aged 95". ESPN Cricinfo. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Walcott p. 14.

- Weekes p. 4.

- Walcott p. 18.

- Sandiford, K. (1995) Everton DeCourcey Weekes, Famous Cricketers Series: No 29, Association of Cricket Statisticians and Historians, Nottingham. ISBN 0-947774-55-6

- Walcott p. 17.

- Spooner, P. (1998) "Sir Everton Weekes: My First Test", The Barbados Nation, 18 December 1998

- Walcott p. 20.

- Sandiford (1995) p. 6.

- Weekes, p. 5.

- Cricket Archive, Trinidad v Barbados scorecard http://www.cricketarchive.co.uk/Archive/Scorecards/17/17467.html Accessed 24 April 2008.

- Cricket Archive, http://www.cricketarchive.co.uk/Archive/Scorecards/17/17469.html Accessed 24 May 2008

- Cricket Archive, Scorecard British Guiana v Barbados in 1946/47 http://www.cricketarchive.co.uk/Archive/Scorecards/17/17878.html Accessed 29 May 2008

- Dyde p. 160.

- Walcott p. 2.

- Walcott p. vii.

- Walcott p. 7.

- Walcott p. 13.

- Walcott p. 15.

- Walcott p. 19.

- "West Indies Cricket: 3Ws Oval, Barbados" http://www.barbados.org/3ws_oval.htm Accessed 27 April 2008

- "West Indies Cricket: 3Ws Monument" http://www.barbados.org/3ws_memorial.htm Accessed 27 April 2008

- Cricinfo, "Scorecard, 1st Test: West Indies v England at Bridgetown, 21–26 Jan 1948" Accessed 27 April 2008

- Belson, F. (1951) "Cricketer of the Year – 1951 Everton Weekes", Wisden Cricketer's Almanack

- Sandiford (1995) p. 13.

- Sandiford, K. (2004) "Everton Weekes – West Indies' Whirlwind", The Journal of the Cricket Society, vol. 21 no. 4 Spring 2004

- The Adelaide Advertiser, "Young West Indian's Test Record" 4 January 1949, p. 10.

- "Fifties in consecutive innings", ESPNcricinfo, Accessed 6 October 2008.

- Lynch, S. (2007) "Losing four times running, and seven fifties in a row", ESPNcricinfo, Accessed 6 October 2008.

- "Cricinfo: Fastest To 1000 Runs". Archived from the original on 13 February 2006. Retrieved 20 May 2007.

- Sobers p. 64

- Cricket Archive, "Indian Cricketer Cricketers of the Year", http://www.cricketarchive.co.uk/Archive/Players/Overall/Indian_Cricket_Cricketers_of_the_Year.html Accessed 27 April 2008.

- Sandiford (1995) p. 16.

- Sandiford (1995) p. 17.

- Canberra Times, "Weekes may play in Second Test, 30 November 1951

- Canberra Times, "West Indies Bad Luck Continues", 21 December 1951

- Goodman, T. "Lindwall's bowling to Weekes was overdone", Sydney Morning Herald, 30 January 1952.

- McGilvray, A. (1989) Alan McGilvray's Backpage of Cricket, Lester Townsend Publishing, Paddington.

- Sandiford (1995) p. 23.

- Basevi, T. & Binoy, G. (2009) "From Charles Bannerman to Ricky Ponting", ESPNcricinfo, 5 August 2009, Accessed 9 August 2009

- Cricket Archive, Scorecard, West Indies v Australia in 1954/55, Sabina Park, Kingston http://www.cricketarchive.co.uk/Archive/Scorecards/21/21455.html Accessed 28 April 2008

- Beckles p. 78.

- Sandiford (1998) p. 22.

- Sandiford (1995) p. 8.

- Sandiford (1995) p. 29.

- Our Cricket Correspondent, "Weekes and West Indies earn Honour in Defeat", The Times, 24 June 1957.

- Armstrong p. 123.

- Sandiford (1995) p. 30

- Kay, J. (1969) "An Invitation from the Forgotten Leagues", The International Cavaliers Cricket Book, Purnell, London

- Edmundson p. 69.

- Edmundson p. 71.

- Lancashire League http://lancashireleague.com/Records/LL1000RUNS.html 1,000 runs in a Lancashire League season Accessed 26 April 2008

- Edmundson p. 125.

- Armstrong p. 122.

- Walcott p. 21.

- Cricket Archive, "Scorecard, Trinidad and Tobago v Barbados in 1963/64", http://www.cricketarchive.co.uk/Archive/Scorecards/26/26610.html Accessed 8 May 2008

- Sandiford (1995) p. 38.

- Bailey (1968) p. 52.

- Majumdar & Mangan p. 139

- Majumdar & Mangan pp. 138–9

- Sandiford (1995) p. 9.

- Bailey (1968) p. 56.

- Sandiford (1998) p. 150.

- Sandiford (1998) p. 23.

- Sandiford (1998) p. 26.

- Sandiford (1995) p. 10.

- Sobers p. 65

- Truscott, A. "Bridge; Can't Be Beat?", The New York Times, 3 July 1988.

- Cricinfo, "Everton Weekes Profile", http://content-www.cricinfo.com/westindies/content/player/53241.html Accessed 24 April 2008.

- Indo-Asian News Service "Sir Everton pens a book" 4 December 2007

- Government of Barbados, Official Gazette, 1986.

- Cricket Archive, "Everton Weekes" http://www.cricketarchive.co.uk/Archive/Players/0/812/812.html Accessed 24 April 2008.

- Cricinfo, "Donald Weekes", http://content-www.cricinfo.com/westindies/content/player/22829.html Accessed 24 April 2008.

- "Sir Everton Weekes: West Indies cricketing great suffers heart attack". BBC Sport. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- Richards, Huw (10 July 2020). "Everton Weekes, Cricket Star and Racial Pioneer, Is Dead at 95". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- "Sir Everton Weekes: West Indies legend dies at 95". BBC. 1 July 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Reuters, "Everton Weekes and Peter Blake Knighted" 16 June 1995.

- Engel, M. "How they were chosen", Wisden Cricketers' Almanack 2000, John Wisden & Co. Ltd, Guildford, Surrey.

- Arthur in Weekes, p. iv.

- Small, M. "A Brit like home", The Sunday Mirror, 14 December 2008, p. 14

- Asian News International, "ICC Launches Cricket Hall of Fame in Association With FICA", 2 January 2009

- Basevi, T. & Binoy, G. "Unsated by a century", ESPNcricinfo, 8 April 2009 http://content.cricinfo.com/magazine/content/story/398018.html?CMP=OTC-FCS Accessed 9 April 2009

- espncricinfo, "Highest Batting Averages in Test Cricket" http://www.cricketarchive.co.uk/Archive/Records/Tests/Overall/Highest_Batting_Average.html Accessed 7 July 2008

References

- Armstrong, G. (2006) The Greatest 100 Cricketers, New Holland: Sydney. ISBN 1-74110-439-4.

- Bailey, T. (1968) The Greatest of My Time, Eyre & Spottiswoode: London. SBN 41326910.

- Beckles, H. (1998) The Development of West Indian Cricket, Pluto Press ISBN 0-7453-1462-7.

- Belson, F. (1951) "Cricketer of the Year – 1951 Everton Weekes", Wisden Cricketer's Almanack.

- Dyde, B. (1992) Caribbean Companion: The A-Z Reference, MacMillan Press, ISBN 0-333-54559-1.

- Edmundson, D. (1992) See the Conquering Hero: The Story of the Lancashire League 1892–1992, Mike McLeod Litho Limited, Accrington. ISBN 0-9519499-0-X.

- McGilvray, A. (1989) Alan McGilvray's Backpage of Cricket, Lester Townsend Publishing, Paddington.

- Majumdar, B. & Mangan, J. (2003) Cricketing Cultures in Conflict: World Cup 2003, Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-8407-4.

- Sandiford, K. (1995) Everton DeCourcey Weekes, Famous Cricketers Series: No 29, Association of Cricket Statisticians and Historians, Nottingham. ISBN 0-947774-55-6.

- Sandiford, K. (1998) Cricket Nurseries of Colonial Barbados: The Elite Schools, 1865–1966, Press University of the West Indies, ISBN 976-640-046-6.

- Sobers, G. (2002) My Autobiography, Headline, London. ISBN 0-7553-1006-3.

- Walcott, C. (1999) Sixty Years on the Back Foot, Orion, London. ISBN 0-7528-3408-8.

- Weekes, E. (2007) Mastering the Craft: Ten Years of Weekes 1948 to 1958, Universities of the Caribbean Press Inc, Barbados. ISBN 978-976-95201-2-7.

External links

- Everton Weekes at ESPNcricinfo

- Obituary on Cricbuzz