Jim Laker

James Charles Laker (9 February 1922 – 23 April 1986) was an English cricketer who played for Surrey County Cricket Club from 1946 to 1959 and represented the England cricket team in 46 Test matches. He was born in Shipley, West Riding of Yorkshire, and died in Putney, London.

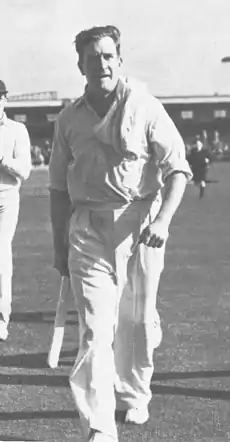

Jim Laker leaves the field after taking 19 for 90 at Old Trafford in 1956. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | James Charles Laker | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 9 February 1922 Shipley, West Riding of Yorkshire | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 23 April 1986 (aged 64) Putney, London | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Batting | Right-handed | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bowling | Right arm off break | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National side | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Test debut (cap 328) | 21 January 1948 v West Indies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Test | 18 February 1959 v Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domestic team information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years | Team | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1946–1959 | Surrey | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1951/52 | Auckland | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1962–1964 | Essex | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Career statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: Cricinfo, 28 April 2018 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A right-arm off break bowler, Laker is generally regarded as one of the greatest spin bowlers in cricket history. In 1956, he achieved a still-unequalled world record when he took nineteen (of a maximum twenty) wickets in a Test match at Old Trafford Cricket Ground in Manchester, enabling England to defeat Australia in what has become known as "Laker's Match". At club level, he formed a formidable spin partnership with Tony Lock, who was a left-arm orthodox spinner, and they played a key part in the success of the Surrey team through the 1950s including seven consecutive County Championship titles from 1952 to 1958. Laker batted right-handed as a useful tail-ender who scored two first-class centuries. He was considered a good fielder, especially in the gully position.

For his achievements in 1951, Laker was selected by Wisden Cricketers' Almanack (Wisden) as one of the five Wisden Cricketers of the Year in its 1952 edition. He was selected as the New Zealand Cricket Almanack Player of the Year in 1952 after playing for Auckland in the 1951–52 season. In 1956, his Surrey benefit season realised £11,086 and, at the end of that year, he was voted "BBC Sports Personality of the Year", the first cricketer to win the award. He later worked for BBC Sport as a cricket commentator in its outside broadcast transmissions.

Early life

Laker's family background was complicated and it was not until Alan Hill researched his biography, published in 1998, that long-term misunderstandings were resolved. For many years, it was generally believed that Laker had been orphaned at an early age and raised by four aunts. Hill was able to consult family members and discover what really happened. The information is presented in the first two chapters of his biography.[1]

Laker's mother was born circa 1878 in the Barnsley area. She was called Ellen Oxby and was the daughter of a railway worker and his wife who had moved to south Yorkshire from their native Lincolnshire. When Ellen was 20, circa 1898, she married a man called James Henry Kane, who was a journeyman printer from Bradford. Over the next few years, Ellen had two daughters, called Mollie and Margaret. Six years later, circa 1906, she had a third daughter called Doreen and, at around the same time, Kane deserted her. Hill discovered that Kane's family ostracised him but there was never a divorce, and so Ellen continued to be known as Ellen Kane.[2]

In order to make ends meet, Ellen followed the example of her sister Emily Oxby and became a schoolteacher of infant and junior children, working at schools in the Shipley district, which is in Airedale, north of Bradford. Some years later, she became involved with a man called Charles Henry Laker.[3] He was a stonemason from Sussex who had moved north to work on Bradford City Hall. They set up home together and a daughter, Susie, was born in 1916. It is not clear from Hill's researches if Charles Laker joined the armed forces during the First World War or if he was in a reserved occupation as a qualified stonemason. In February 1922, the family were living in Shipley at 36, Norwood Road, which is where Jim, originally known as Charlie, was born.[4] In 1924, Charles Laker also deserted Ellen, who again had to pick up the pieces and rely on school teaching to feed the family.[5]

Laker was two years old when this happened and was told that his father had died. He maintained that he had no recollection of his father and had never even seen a photograph of him. In the 1980s, only a few years before Laker's death, he discovered that his father had moved to Barnoldswick and had died there in 1931 after working locally as a stonemason. It transpired that Laker senior had left Ellen to live in Barnoldswick with a woman called Annie Sutcliffe. She was buried beside him, having died in 1959, and it is possible that she knew about her famous quasi-stepson.[6]

Meanwhile, the Kane family pulled together and, as Hill says, "ringfenced" the situation.[5] They told everybody that Charles Laker had died and, in due course, presumably after moving house from Norwood Avenue to nearby Carmona Avenue, that Ellen, Mollie, Margaret and Doreen were all sisters and were the aunts of orphans Susie and Jim. In 1924, Ellen was working at the church school in Calverley. As Hill asserted, the priority in those times was to "silence gossip-mongering" and protect the vital teaching role. Ellen was therefore, correctly, Mrs Kane at school but, not so, she assumed the pretence of "aunt".[7] Mollie and Margaret had already left home but were still living in the Shipley area. Apparently, no one who knew the family thought that Ellen was the mother of Susie and Jim. It was simply accepted that they were orphans and she was their aunt. Hill discovered that the children sometimes resided with a family living over a grocer's shop in Baildon. It seems that this was Margaret's family so the children on those occasions were staying with "another aunt", in fact their half-sister, perhaps if Ellen was ill or for work reasons.[8]

In the years around 1930, Ellen was employed at Frizinghall Council School, which Laker attended until 1932.[9] He was very intelligent and, with the added advantage of being taught by his mother, was able to win a grammar school scholarship. This entitled him to a free place at the Salts High School in nearby Saltaire.[10] He enrolled at Salts in September 1932 and remained for seven years, later saying that he was very happy there.[11] It was around 1932 that Ellen took up with a new partner, called Bert Jordan. This was a sound relationship and Laker was able to enjoy a settled home life through his senior school years. The family moved to Kirklands Avenue in Baildon. Doreen married and went to live in Eastbourne. In due course, Susie married and moved on too, but Laker lived with Ellen and Bert until he joined the Army in 1941. He left school in February 1939 and obtained full-time employment at Barclays Bank in Bradford city centre, working a nine-hour day for £5 a month.[12]

Ellen was distraught when Laker volunteered for active service, especially as he lied about his age and said he was twenty.[13] She tried to convince the Army that Laker was under-age, although he was not, but to no avail. Laker went to Leicestershire for infantry training and was then posted to the Royal Army Ordnance Corps (RAOC), serving in the Middle East. He set sail a few days later and, until 1945, served in Palestine and Cairo, although he was never involved in front line fighting.[13] Laker returned to England on leave in 1945 but things had changed while he was away. Bert had died during the war and Ellen was forced to sell the house in Baildon. She had moved to Manningham, not far from Valley Parade (Laker was a lifelong Bradford City supporter), and was still working as a supply teacher even though she was 66. Her health had declined and Laker was worried about her. Shortly before his leave was due to end, she suggested that he visit Doreen in Eastbourne. He agreed and, while he was travelling, she collapsed and died of a massive heart attack. She managed to leave him an estate worth £1,000, which was fairly substantial at the time. With Susie and his half-sisters all married, Laker's northern roots were broken and he no longer had any pressing reason to return to Bradford. He was able to keep his options open when his military service ended.[14]

He had to return to Egypt, by way of Italy, before he was finally repatriated but he still had a year of service to perform before demobilisation. He was posted to the Shorncliffe barracks at Folkestone in late 1945 and spent a month there in freezing cold conditions. He then negotiated a transfer to the War Office itself, in central London. He was invited by an army friend called Colin Harris to lodge with his family in Forest Hill, a couple of miles from Catford. It was meant to be a temporary arrangement but Laker ended up living with the Harris family for over five years, until he was due to get married himself. His demobilisation was in August 1946 and he had the option of a permanent career, perhaps even a commission, in the Regular Army. He considered a return to banking and asked Barclays if they would reinstate him and transfer him to a London branch. They agreed, but as Fred Robinson, one of Laker's old school friends later told Alan Hill, "neither of those ventures ever really came within his considerations".[15]

The reason why Mr Robinson held that opinion was because Laker had, through many years, developed into a cricketer of enormous potential. As soon as he was demobbed, Surrey County Cricket Club offered him a professional contract which he signed, having gained permission from Yorkshire County Cricket Club.[16] He had already made his first-class debut for Surrey a month earlier and, only seventeen months later in January 1948, he made his Test debut for England at the Kensington Oval in Bridgetown, Barbados.[17]

Development as a cricketer to 1946

Laker played cricket continuously from an early age with the full encouragement of his mother, who was a lifelong enthusiast of the game. Alan Hill was told by Susie's son that Ellen used to make Susie bowl to Laker because she was convinced he had the makings of a batsman. He was a regular member of the Salts High School team, playing primarily as a batsman but also as a fast bowler. In March 1938, aged 16, he was invited to attend special coaching by Yorkshire in their winter shed at Headingley.[18] Soon afterwards, on Yorkshire's recommendation, he joined Saltaire Cricket Club, who played in the Bradford Cricket League, and made his debut for them at their Roberts Park ground against Baildon, his local club. Hill recounts that Ellen tried without success to sabotage his debut by trying to get Laker into the Baildon team. He played for Saltaire for three seasons, on one occasion scoring a century.[19] In the 1938 season, his last at school, he played for Salts HS on Saturday morning and for Saltaire CC in the afternoon.[20]

Laker recalled that Ellen took him to Leeds to buy new cricket gear at Herbert Sutcliffe's shop. He said the sacrifice she made was "frightening to contemplate" but she was determined to see him succeed as a cricketer.[21] Yorkshire's coaching sessions were run by the former county batsman Benny Wilson, who was the first to show Laker how to spin the ball and encourage him to develop the skill. Although Wilson ran the teenage coaching classes, Laker was also coached by former Yorkshire players George Hirst, Maurice Leyland, Emmott Robinson and Alfred Wormald.[22] Laker still thought of himself as a batsman and his contemporary Ronnie Burnet, who became Yorkshire's captain in the late 1950s, recalled that Laker bowled a mixed bag of "fast off-cutters-cum-spinners" before the war. Charlie Lee, one of Laker's Saltaire team-mates, had a similar recollection saying that "Jim bowled all sorts of stuff and generally enjoyed himself without ever appearing to have the makings of a great bowler".[18]

Although Laker did enough at Saltaire to be well remembered, his cricketing career really gathered pace and took off while he was with the RAOC in Egypt. Playing on coconut matting wickets in inter-service matches, he decided to develop the off spin technique he had been taught by Benny Wilson. He recalled that, "to my utter amazement", he could turn the ball "quite prodigiously" on these matting strips.[23] John Arlott later wrote that English cricketers in Egypt were writing home and talking about "a Yorkshire lad who could bowl off spin like a master".[23] In 1943, Laker went to Alexandria to play for the RAOC against an RAF team and took five wickets for ten runs including a hat-trick. In 1944, he played against a South African Air Force XI, scored a century and then took six wickets for ten runs. In these matches, he encountered several top-class players including Norman Yardley, Peter Smith, Bert Sutcliffe, Ron Aspinall, Dudley Nourse and Arthur McIntyre.[24]

Although Laker would have loved to play for Yorkshire, his circumstances after the end of the war led almost inevitably to his being approached by Surrey. While he was resident with the Harrises at Forest Hill, he continued to play for service teams and, in March 1946, he joined Catford Cricket Club.[25] Some impressive performances for Catford, including ten for 21 against Bromley, were noted by Andrew Kempton, Catford's club president, who was a member of the county club. Kempton knew Andy Sandham, the former England opening batsman who was Surrey's coach in 1946, and recommended Laker. Sandham invited Laker for a trial at The Oval.[26] Soon afterwards, on 17 July, Laker made his first-class debut when Surrey hosted a Combined Services team, whom they defeated by six wickets. Laker had the creditable figures of three for 78 and three for 43. He was still in the RAOC at the time but was demobilised in August; Surrey immediately offered him a professional contract, subject to Yorkshire's approval.[27] Yorkshire agreed to his release and Laker signed for Surrey on terms of £6 a week in winter, augmented by match fees in summer.[16] Laker played in two more first-class matches near the end of the season.

First-class and international career

1947 to 1950

Laker bowled well at county level in 1947, taking 79 wickets and topping the Surrey bowling averages. His best performances were at Portsmouth, where he dismissed Hampshire with eight for 69, and at Chelmsford, where he took seven for 94 against Essex.[28] Near the end of the season, he was invited to play for Pelham Warner's XI against the South of England in a Hastings Festival match. Whether he knew it or not at the time, this match was effectively a Test trial. He did very well, taking eight wickets in the match, including a second innings hat-trick.[29]

Soon afterwards, he was selected by Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) for their 1947–48 tour of the West Indies. He played in four Tests and, on debut, took seven for 103 in the first innings of the first Test. This tour was a disaster for MCC and the 1947 edition of Playfair Cricket Annual (Playfair) headlined it as "An Ill-Starred Venture".[30] Planning and preparation were poor and the team was badly led by Gubby Allen. Playfair said Laker was the only player who "really justified his selection".[30] In its 1948 edition, Wisden said that the discovery of Laker was "very satisfactory" for Surrey. He was described as specialising in off breaks, "fielding smartly" in the gully and showing promise as a batsman.[27]

Still inexperienced at Test level, Laker came in for some heavy punishment when he played in three Tests against the 1948 Australians and that failure created doubt in the minds of England's team selectors. Despite his continuing success for Surrey, Laker could not afterwards find a regular place in the England team until 1956 and went on only one international tour, to the West Indies again in 1953–54, between those in 1947–48 and 1956–57. England's worst performance in the 1948 series was at Headingley: they actually played well for the first four days and set Australia a seemingly impossible last day target of 404 to win. Australia, led by Don Bradman, won by seven wickets.[31] Godfrey Evans said the England team was complacent because no one had ever achieved such a target before in Test cricket. Evans himself was a prime culprit because he missed stumping chances, including one off Laker with Bradman beaten and out of his ground. Bradman later said that it was the key moment of the Australian innings.[32] In the match as a whole, Laker bowled 62 overs and took three wickets for 206 runs. Despite being a disappointing outcome, it was against an outstanding team that was unbeaten in the whole tour. The situation was well summarised by Playfair saying that England needed "a leg-spinner or a Verity" (Hedley Verity was a slow left arm orthodox bowler) but they had neither. The implication was that the pitch was not one on which an off-break bowler such as Laker could succeed. Playfair went on to criticise "tactical errors, missed chances and a sad lethargy in the field".[33] Playing for Surrey in 1948, Laker took 79 wickets and the team were runners-up in the County Championship behind first-time winners Glamorgan.[34]

Alan Hill recorded that, while Laker may not have enjoyed the 1948 Headingley Test match, its host club were very concerned indeed that Yorkshire-born Laker had eluded their attention. Fred Trueman later recalled that the Yorkshire club president Ernest Holdsworth contacted Laker in 1948 and invited him to dinner at a London restaurant. Laker accepted but was then astonished when Holdsworth tried to persuade him to return and play for Yorkshire. Although Laker did not like the social divide in place at Surrey, he wished to stay with his adopted county and thanked Holdsworth for the offer, which he declined. Len Hutton recalled that, also in 1948, he was asked by the Yorkshire committee to make some discreet enquiries about Laker's situation in Surrey. He reported back that Laker was content where he was and did not wish to play for Yorkshire. Hutton agreed that Yorkshire "went on needing Laker badly" and ruefully admitted that he "tied us in all sorts of knots" in Yorkshire's matches against Surrey.[35]

After the Headingley match, Laker was omitted from England's team in the final Test at The Oval, his home ground. England toured South Africa in 1948–49 but he was not selected. The preferred spinners were Jack Young (slow left arm orthodox spinner), Roly Jenkins and Doug Wright (both leg break and googly). No specialist off spinner was included in the squad. England won the five-match series, defeating South Africa by two Tests to nil with three drawn. In 1949, Laker played in only one of the four Tests against New Zealand even though he took 122 wickets in the season and was easily one of the most outstanding English bowlers. In this series, England chose Eric Hollies, another leg spinner, in all the matches and Laker's only selection was a tactical one, in the final Test at The Oval, replacing a pace bowler with an extra spinner for that venue. England had no overseas tour in the winter of 1949–50.

In 1950, Laker took eight wickets for only two runs in an innings in a Test trial at Bradford Park Avenue when playing for England against "The Rest". The match, scheduled for three days, began on Wednesday, 31 May with a chill wind blowing. The wicket had been uncovered and was drying after recent rain, which meant that a spinning delivery would act unpredictably when pitched. Laker took full advantage. He set an attacking leg side field and bowled around the wicket, concentrating on line and length with minimal flight, which gave the batsmen no time to come forward to the pitch of the ball. Some balls would gain extra bite from the pitch surface and rear up while others would "turn" to an unexpected degree. The Rest were all out before lunch for only 27. Batting conditions improved afterwards and England went on to win by an innings inside two days.[36] As a Test trial, the match was of no use to the selectors and it was argued afterwards that the pitch should have been covered or, failing that, the England team should have batted first.[37] One certainty that the match ensured was that Laker would play in the first Test that summer against the West Indies.[38] Unfortunately, Laker injured his hand when batting in the Test, which impaired his bowling. He took only one wicket in the match, which England won, and the selectors decided to leave him out of the team thereafter. Without him, England lost the series one to three.

Although Laker took 166 wickets in 1950, his highest-ever season tally, the selectors continued to ignore him when they chose their squad to tour Australia in 1950–51. England, hopelessly outclassed and under poor leadership, lost the first four Tests before managing a consolation victory in the fifth. Laker accepted an invitation to tour India and Ceylon with a Commonwealth XI, playing in ten matches and taking 36 wickets. The Commonwealth squad was a multi-talented group considered stronger than the England one touring Australia.[39] It was nominally captained by Les Ames but, because of injuries, he handed over to Frank Worrell.[39] The Commonwealth XI were undefeated in 29 matches played between 1 October and 6 March, including four unofficial "tests" against India and one against Ceylon. Laker had to return home in early December because of sinusitis but he enjoyed the tour.[40] He later recalled one incident when a huge rat ran across the field and onto the pitch just as he was about to bowl. Laker stopped and was then astonished to see a kite hawk swoop down, seize the rat in its talons and fly away with it. Laker was used to pigeons on the field at The Oval. He was so surprised by this that when he did the bowl the next ball, it bounced twice and was struck to the boundary.[41]

1951 to 1955

After his recovery from sinusitis, Laker got married just before the 1951 season.[42] He took 149 wickets that season and played in two of the five Tests against South Africa. In the final Test at The Oval, he took ten wickets in the match for 119 runs and England won by four wickets. His main competitors for a place were Johnny Wardle (slow left arm orthodox) and Roy Tattersall, another off spinner. Tattersall played in all five matches.

Laker went to New Zealand in the winter of 1951–52 as a player-coach for Auckland, taking his wife with him for what was effectively an extended honeymoon. He played in four matches for Auckland, taking 24 wickets. The Lakers were in New Zealand for five months and liked it so much that they seriously considered emigrating there. Laker decided that, on balance, his cricketing future was in England and regretfully declined an offer from the Auckland Cricket Association to re-engage as player-coach in 1952–53.[43]

In 1952, the season in which Surrey won the first of their seven consecutive County Championship titles, Laker played in four Tests against India. In 1953, he played in three Tests against Australia, including the series decider at The Oval in which England won The Ashes for the first time in twenty years. He toured the West Indies again with MCC in 1953–54, playing in seven matches including four Tests and taking 22 wickets. He played in one Test against Pakistan in 1954 but was not chosen for the 1954–55 tour of Australia. He played in one Test against South Africa in 1955.

1956

Laker finally secured his Test place in 1956 and took part in all five Tests against Australia. He took all ten wickets in an innings for Surrey against the Australians. This was the first time a bowler had taken all ten against the Australians since Ted Barratt in 1878.[44] Laker took 46 wickets in the 1956 Ashes series to establish a still-unbroken record for a five-match Test series between England and Australia, but Sydney Barnes still holds the world record of 49 wickets taken in 1913–14 for England in South Africa. Laker's effort led to him being awarded the BBC Sports Personality of the Year Award in 1956, the first cricketer to win the award. Surrey won the County Championship for the fifth consecutive time in 1956. Roy Webber's history of the competition was published soon afterwards and, in his review of the contemporary county teams, he wrote that "it is difficult to imagine a better and more balanced bowling attack than that presented by Alec Bedser, Peter Loader, Stuart Surridge, Jim Laker and Tony Lock".[45]

"Laker's Match"

In its report of the fourth Test at Old Trafford, Wisden began by saying that "this memorable game will always be known as Laker's Match because of the remarkable performance by the Surrey off-break bowler in taking nine wickets for 37 runs in the first innings and ten wickets for 53 in the second".[46] The match took place from Thursday, 26 to Tuesday, 31 July. England, who had won the toss and decided to bat first, won the match by an innings and 170 runs.[47]

England batted until mid-afternoon on the Friday and amassed a total of 459, which included centuries by Peter Richardson and David Sheppard. In reply, Australia were dismissed for 84 and, following on, reached 53 for one at the close. In Australia's first innings, England's two pace bowlers, Trevor Bailey and Brian Statham, bowled only ten overs between them before Laker and Lock were introduced. Laker began from the Warwick Road End but did not take a wicket until he switched to the Stretford End. Before tea, when Australia were 62 for two, he dismissed opener Colin McDonald, who was caught by Lock for 32, and Neil Harvey, who was bowled without scoring. Lock took the wicket of Jim Burke, caught by Colin Cowdrey at slip, with the first ball bowled after tea and England dominated from then on. In only 37 minutes from the restart, Australia collapsed to 84 all out. Laker terminated the innings by taking the last seven wickets for only eight runs in just 22 deliveries. His figures were nine for 37 while Lock's were one for 37.

Australia were asked to follow-on and had reached 28 for no wicket when McDonald suffered a knee injury which forced him to retire hurt. Harvey replaced him and was out first ball after hitting Laker to Cowdrey at short mid-on. Australia's best batsman had collected a "pair" and, despairingly, threw his bat into the air as he departed. Burke and Ian Craig put up some resistance and were still together at the close. According to Wisden, the Australians made a protest about the pitch on Friday evening and accused the hosts, Lancashire County Cricket Club, of preparing a pitch suited to spin bowling. Lancashire strongly denied the charge. Australian captain Ian Johnson made no public comment about the issue.

It then seemed as if the match was doomed to be ruined by the weather as only 47 minutes of play were possible on the Saturday and only an hour on the Monday. During that time, Australia lost Burke to Laker and reached 84 for two with McDonald (who returned when Burke was out) and Craig batting.[48] On Tuesday, the final day, conditions improved and play began only ten minutes late. McDonald did his best and put up a strong defence, eventually scoring 89. Craig, who made 38, stayed with him until lunch when the score was 112 for two. With four hours left, there seemed to be a reasonable chance that Australia would escape with a draw. The morning had been cloudy and the sun began to shine as lunch was taken. This caused the ball to spin quickly and create increased problems for the batsmen. During the afternoon session, Laker took four wickets in nine overs for three runs but then Richie Benaud joined McDonald and they stayed together for 75 minutes to the tea interval. The pitch was taking prodigious spin after tea and Australia's hopes faded when Laker dismissed McDonald with the second ball of the evening session. At 17:27, with just over an hour to go, Laker bowled to Len Maddocks and appealed for leg before wicket. Maddocks was given out and Laker had taken all ten wickets for 53 runs to give England victory.[46]

Wisden pointed out that the rain returned on Tuesday night and, on the Wednesday, the entire first-class programme was washed out. Wisden commented that "it can be seen how close was England's time margin, and how the greatest bowling feat of all time nearly did not happen".[46] Writing in 2005, Richie Benaud recalled that there was rain in the Old Trafford area on the final day itself but it did not fall at the venue. Benaud was so impressed by Laker that he decided to shorten his own run-up and, he said, "my bowling attitude".[49] In its match report, Playfair said that Laker "had enjoyed one of the most remarkable bowling performances that has ever been seen on a cricket field". The 1957 edition of Wisden included an article by Neville Cardus that paid tribute to Laker's performances in 1957.[50]

Laker's ten for 53 was the first time a bowler had taken all ten wickets in a Test innings. The only other bowler to achieve the feat is India's Anil Kumble, who took ten for 74 at Delhi's Feroz Shah Kotla against Pakistan in 1999.[51] Including Laker himself with nine for 37 in the first innings, there have been 17 instances of a bowler taking nine wickets in a Test match innings.[51] Laker's match bowling figures of nineteen for 90 remain a world record in first-class cricket.[52] The record for the most wickets taken in a Test match was previously held by England's Sydney Barnes who took seventeen for 159 at the Old Wanderers, in Johannesburg, against South Africa in December 1913. Barnes remains the only bowler other than Laker to take seventeen in a Test match.[52] Two common factors link Laker and Barnes. They are the only two bowlers who have taken seventeen or more wickets in a Test match and they both played for Saltaire in the Bradford League, Barnes from 1915 to 1923, Laker from 1938 to 1940.[53] Laker is the only bowler to have taken more than eighteen wickets in a first-class match. There had been 23 previous instances of seventeen or more in a match but, since Laker's feat, only John Davison of Canada in 2004 and Kyle Abbott of Hampshire in 2019 have taken seventeen wickets in a match.[52]

1956–57 to 1964

Laker toured South Africa with MCC in 1956–57, playing in fourteen matches including all five Tests. He took fifty wickets, which was his career-best tally in an overseas season. He played in four Tests against the West Indies in 1957 and four against New Zealand in 1958.

The 1958 season was the last of Surrey's seven consecutive County Championships but it was marred by a quarrel between Laker and the team captain Peter May, who had accused Laker of "not trying" in a match against Kent at Blackheath in July. Kent won the match by 29 runs. Laker bowled a total of 54 overs in the match and that immediately followed a haul of 63 overs in a match against Glamorgan at Swansea, which Surrey won. It seems that Laker's spinning finger was definitely suffering from "wear and tear" at the time and this probably reduced his effectiveness. His colleagues held differing views about the matter. Peter Loader said May was completely out of order while Micky Stewart suggested that May should have been aware that "Jim was knackered". Godfrey Evans, who played for Kent in the match, said that Laker was "ill-supported by May". Raman Subba Row blamed May for his "management style" which was not at all people-oriented, unlike that of Stuart Surridge, May's predecessor as Surrey captain, who was a "people person" and "down to earth". On the other hand, Arthur McIntyre blamed Laker for his batting in the Kent match because he "holed out" and made a more general comment about Laker "crying wolf" over injuries to his fingers.[54]

On England's disastrous tour of Australia in 1958–59, Laker was one of the few players to enhance his reputation, bowling well on unhelpful pitches. He played in ten matches including four Tests. The fifth Test at the Melbourne Cricket Ground in February was his last. He was not selected by England for the series against India in 1959. He retired from playing at the end of the season, in which Surrey surrendered the title to Yorkshire. His final match for Surrey was against Northamptonshire at The Oval in September. Surrey lost by four wickets and Laker took only one wicket.

In 1960, Laker's ghost-written autobiography Over To Me was published. It was controversial because it contained severe criticism of May, especially about the row which followed the match against Kent at Blackheath in 1958.[55] Hill says that the book "testified primarily to Laker's abiding dislike of the social chasm in cricket" created by amateurism.[56] Micky Stewart commented on Laker's view that the game should not be run by the "traditional Oxbridge axis" by saying Laker firmly believed that ability and not background were what counted in administration of the sport, but Stewart added that Laker had no problems with Oxbridge amateurs who were capable.[57] Official displeasure with Over To Me led to the withdrawal by Surrey of Laker's free entry pass to facilities at The Oval. Soon afterwards, the MCC decided to support Surrey and cancelled Laker's honorary membership.[58] Both were eventually restored. Surrey reinstated his free entry pass in 1964 and the MCC his honorary membership in 1967.[59]

In 1962, Laker was "persuaded" out of retirement by his old England team-mate Trevor Bailey and, as an amateur, played in twenty matches for Essex before retiring for good in 1964. He remained a formidable bowler through 1962 and 1963, but he was less so in 1964.

Statistical summary

For the details of this, see the Playfair annuals of 1960 and 1965. Alan Hill's biography has an extensive career stats appendix compiled by Paul E. Dyson, starting on page 215.

Laker played in 450 first-class matches and took a total of 1,944 wickets. His best return was ten for 53 in the 1956 Test at Old Trafford. His career average was 18.41 runs per wicket (any long-term career average below 20 is considered exceptional). He captured five wickets in an innings on 127 occasions and ten wickets in a match 32 times. First-class statistics include Test matches. Laker played in 46 Tests and took 193 wickets at the average of 21.24, which is exceptional at that level of competition. His best return was, again, ten for 53. He took five wickets in an innings nine times and ten in a match three times. He first took 100 wickets in a season in 1948 and achieved the target in eleven consecutive seasons to 1958 with a highest tally of 166 in 1950. His best season average was an outstanding 14.23 in 1958, the last year of Surrey's run of seven titles. Laker's best overseas tally was 50 in 1956–57 on the MCC tour of South Africa. His best overseas average was 15.79 in 1951–52 when he played for Auckland.

Although Yorkshire considered Laker a potential batsman when they invited him for trials at Headingley, his focus on bowling meant that he was never more than a useful tail-ender. Nevertheless, he scored two first-class centuries (113 his highest score) and had one score of 99 among eighteen half-centuries. He was considered a good fielder, especially at gully. His best season as a fielder was 1954 when he held 29 catches in as many matches. In total, Laker held 270 career catches and scored 7,304 runs at the modest average of 16.60.

Issues with amateurism

According to the former amateur player Charles Williams, Laker was a "serial complainer" about "shamateurism". Unfortunately, however, he sometimes spoke and acted unwisely in his opposition to the amateur concept which, in any event, was abolished only three years after he retired.[60]

In March 1958, an MCC sub-committee delivered a report on the continuance of amateurism with special emphasis on the question of broken-time payments. Soon afterwards, Laker addressed a meeting of The Cricket Society and declared that a cricketer who can't afford to play as an amateur should either turn professional or stop playing. He described broken-time payments as "poppycock" because they were "payments on the side" that enabled amateurs to make more money than professionals; even so, he was not saying anything new as the issue pre-dated even the Grace brothers.[61] After MCC announced their squad to tour Australia in 1958–59, Laker proposed to turn amateur for the duration of the tour and then become a professional again on his return to Surrey. His thinking was based on the possible misinformation that amateurs on the tour would be paid an allowance of £1,000 to cover their expenses while the professionals were to receive a fee of £800. MCC refused his request. Williams wrote that Laker ruined his case through characteristic bluntness and by not fully understanding the reasons why amateurism existed, rightly or wrongly, in the first place. Ironically, Laker did end up playing as an amateur when he came out of retirement to join Essex in 1962.[62]

Style and personality

In the 1986 Barclays World of Cricket, Colin Cowdrey wrote a mini-biography of Laker, whom he praised as "perhaps the best off-spin bowler the game has seen".[63] Cowdrey described Laker as the "perfect model" for an aspiring slow bowler because he was tall and strong with big hands and a high action. Laker's strength gave him the capability to undertake long spells of bowling. His varied flight of the ball was difficult for the batsman to predict and, if he was given any assistance by pitch or weather conditions, Laker could generate extra pace and spin so as to be at times "almost unplayable".

John Arlott once wrote that batsmen at the non-striking end "could hear the ball buzz" as Laker imparted spin on to it.[64] Garry Sobers agreed with him, saying that "you could hear the ball fizz as Jim spun it".[65] Sobers said that Laker was the "undoubtedly the best off-spinner I ever saw" with Lance Gibbs not far behind. Sobers was especially wary of Laker's straight ball because, unusual among spinners, it was delivered at lesser pace than his spinning deliveries and it "drifted" (i.e. it was an outswinger).

Fred Trueman, who knew and got along with Laker very well, described him as "a modest, laconic, sometimes dour guy".[66] Like everyone else in cricket, Trueman was astounded by Laker's world record at Old Trafford in 1956 but was more impressed by Laker's "self-effacing" reaction to the achievement. As Trueman says, photographs of Laker in the next day's newspapers show him strolling towards the pavilion, not even smiling, sweater over his shoulder, "as if returning from net practice".[67] Trueman went on to say how he "shuddered to think" what sort of posturing would ensue in the unlikely event that Laker's performance should be matched by a 21st-century cricketer.

In Peter May's autobiography, he wrote about how Arthur McIntyre kept superbly to the great Surrey bowling attack of Bedser, Loader, Laker and Lock on difficult wickets. McIntyre himself said that, of the four, he had the greatest difficulty keeping wicket to Laker who "spun the ball so viciously".[68]

In 2006, Peter Richardson considered the differences between Laker and Lock, saying that Laker was "slightly cynical, difficult to connect with, laconic and moody". Richardson said that Laker and Lock did not get on together and were always competing. Their approaches to the game differed as Lock "would attack" while Laker just kept "chipping away". Richie Benaud had also noted their different characteristics in the way they appealed for a dismissal: "Laker was apologetic, Lock a demander". May, who was Laker's Surrey captain after Stuart Surridge retired in 1956, said that the mere idea of Laker showing enthusiasm was "absurd".

Personal life and post-retirement

Having recovered from the sinusitis he contracted in India in December 1950, Laker began to think seriously about marriage. He had courted his fiancée Lilly for some years. She was born in Vienna but, opposed to Nazism, she left Austria after the Anschluss and was in the Middle East when World War II began. She joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service in Cairo and met Laker when he was posted there with the RAOC.[69] They worked in the same office and then met again in London at a service reunion event. They decided to marry on 27 March 1951 at the Kensington register office and spent a rain-swept honeymoon in Bournemouth before the cricket season began.[42] Lilly survived Laker by many years. She and their daughters Fiona and Angela helped Alan Hill with his research for Laker's biography.[9]

Being Austrian, Lilly did not know much about cricket. She took numerous congratulatory telephone calls after his 19-wicket feat and, when Laker arrived home, she asked him: "Jim, did you do something good today?"[70]

In July 1956, only three weeks before his record-breaking performance at Old Trafford, Laker was Roy Plomley's guest on his Desert Island Discs radio programme. His musical choices included Ol' Man River by Paul Robeson, songs by Vera Lynn and Gracie Fields and classical pieces by Pietro Mascagni and Franz Schubert. His luxury choices were a piano and a cricket ball.[71]

Laker developed an interest in broadcasting and, after he retired from playing, became a highly regarded cricket commentator for ITV in the 1960s and then for BBC Television during the 1970s and 1980s. Fellow commentator John Arlott described Laker's commentary style as: "Wry, dry, laconic, he thought about cricket with a deep intensity and a splendidly ironic point of view"[72] whilst Colin Cowdrey praised Laker's "brand of television commentary" that made him a respected figure in the medium. Ted Dexter, as a summariser, worked with commentators Laker and Richie Benaud at the BBC and later remarked on how "a new style of interpretation had evolved as ball-by-ball commentary became their preserve", their trademarks being "patience, accuracy and persistence".[73]

Laker was still employed by the BBC when he died in Putney, aged 64, on 23 April 1986.[74] The cause of death was complications from gall bladder surgery. His body was cremated at Putney Vale Crematorium and his ashes were scattered at The Oval.

References

- Hill 1998, pp. xiv–xv, 1–36.

- Hill 1998, p. 2.

- Hill 1998, p. 3.

- Hill 1998, p. 1.

- Hill 1998, p. 4.

- Hill 1998, pp. 4–5.

- Hill 1998, p. 5.

- Hill 1998, pp. 6–7.

- Hill 1998, p. 6.

- Hill 1998, p. 7.

- Hill 1998, p. 8.

- Hill 1998, pp. 8–9.

- Hill 1998, p. 26.

- Hill 1998, pp. 31–32.

- Hill 1998, p. 35.

- Hill 1998, p. 42.

- Hill 1998, p. 50.

- Hill 1998, p. 16.

- Hill 1998, pp. 15–16.

- Preston, Norman (1952). "Cricketer of the Year 1952 – Jim Laker". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- Hill 1998, p. 15.

- Hill 1998, p. 14.

- Hill 1998, p. 27.

- Hill 1998, pp. 27–33.

- Hill 1998, p. 36.

- Hill 1998, p. 40.

- Wisden 1948, p. 466.

- Hill 1998, pp. 45–46.

- Hill 1998, p. 48.

- Playfair 1947, p. 11.

- Hill 1998, p. 54.

- Hill 1998, pp. 55–56.

- Playfair 1949, p. 58.

- Playfair 1949, pp. 88–90.

- Hill 1998, p. 62.

- Arlott 1984, pp. 261–262.

- Arlott 1984, p. 262.

- Arlott 1984, p. 263.

- Hill 1998, p. 74.

- Hill 1998, p. 76.

- Hill 1998, p. 75.

- Hill 1998, pp. 76–77.

- Hill 1998, p. 78.

- Lemmon 1989, p. 245.

- Webber 1957, p. 103.

- "Fourth Test Match – England v Australia 1956". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. 1957. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- "4th Test, Manchester, July 1956, Australia tour of England – summary". ESPNcricinfo. London: ESPN Sports Media Ltd. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- Playfair 1957, p. 41.

- Benaud 2005, p. 169.

- Cardus, Neville (1957). "Laker's wonderful year". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- "Best Figures in an Innings (Test matches)". ESPN cricinfo. London: ESPN Sports Media Ltd. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- "Best Figures in a Match (first-class)". ESPN cricinfo. London: ESPN Sports Media Ltd. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- Hill 1998, pp. 20–22.

- Hill 1998, pp. 166–167.

- Birley 1999, p. 290.

- Hill 1998, p. 159.

- Hill 1998, p. 160.

- Swanton 1977, p. 92.

- Hill 1998, p. 175.

- Williams 2012, pp. 93–94.

- Williams 2012, pp. 129–130.

- Williams 2012, p. 184.

- Swanton, Plumptre & Woodcock 1986, p. 200.

- Arlott 1984, p. 261.

- Sobers 2003, p. 200.

- Trueman 2004, p. 193.

- Trueman 2004, p. 194.

- Smith 2013, pp. 67–69.

- Hill 1998, pp. 68–69.

- Steen, Rob (30 July 2006). "Heroes & villains". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- "Jim Laker". Desert Island Discs. London: BBC Home Service. 9 July 1956. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- Arlott, John (24 April 2008). "From the Vault: Arlott on Laker". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- Swanton, Plumptre & Woodcock 1986, p. 666.

- "Obituary – Jim Laker". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. 1987. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

Bibliography

Biographical

- Hill, Alan (1998). Jim Laker: A Biography. London: Andre Deutsch Ltd. ISBN 978-02-33050-43-0.

- Laker, Jim (1960). Over To Me. London: Frederick Muller Ltd. ASIN B0000CKKU2.

Annual reviews

- Playfair Cricket Annual. London: Playfair Books Ltd. 1947–1965.

- Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. Ltd. 1947–1965.

Miscellaneous

- Arlott, John (1984). Arlott on Cricket. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-00-02180-82-5.

- Swanton, E. W.; Plumptre, George; Woodcock, George, eds. (1986). Barclays World of Cricket. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-00-02181-93-8.

- Benaud, Richie (2005). My Spin on Cricket. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-03-40833-93-3.

- Birley, Derek (1999). A Social History of English Cricket. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-18-54106-22-3.

- Lemmon, David (1989). The History of Surrey County Cricket Club. London: Christopher Helm (Publishers) Ltd. ISBN 978-07-47020-10-3.

- Smith, Martin, ed. (2013). The Promise of Endless Summer: Cricket Lives from the Daily Telegraph (Telegraph Books). London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-17-81310-48-9.

- Sobers, Garry (2003). My Autobiography. London: Headline Publishing Group. ISBN 978-07-55310-07-4.

- Swanton, E. W. (1977). Follow On. Glasgow: William Collins. ISBN 978-00-02162-39-5.

- Trueman, Fred (2004). As It Was. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-14-05041-48-5.

- Webber, Roy (1957). The County Cricket Championship: A history of the competition from 1873 to the present day. London: Phoenix House Ltd. ASIN B0000CJNYB.

- Williams, Charles (2012). Gentlemen & Players: The Death of Amateurism in Cricket. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson (Orion Publishing Group). ISBN 978-07-53829-27-1.

| Sporting positions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Gordon Pirie |

BBC Sports Personality of the Year 1956 |

Succeeded by Dai Rees |