Francis Younghusband

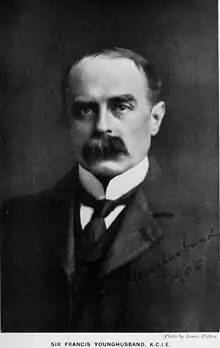

Lieutenant Colonel Sir Francis Edward Younghusband, KCSI KCIE (31 May 1863 – 31 July 1942) was a British Army officer, explorer, and spiritual writer. He is remembered for his travels in the Far East and Central Asia; especially the 1904 British expedition to Tibet, led by himself, and for his writings on Asia and foreign policy. Younghusband held positions including British commissioner to Tibet and President of the Royal Geographical Society.

Sir Francis Younghusband | |

|---|---|

Francis Younghusband c. 1905 | |

| Born | 31 May 1863 |

| Died | 31 July 1942 (aged 79) |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Royal Military College, Sandhurst |

| Occupation | British Army officer, explorer, and spiritual writer |

| Spouse(s) | Helen Augusta Magniac |

| Awards | Order of the Star of India Order of the Indian Empire Charles P. Daly Medal (1922) |

Early life

Francis Younghusband was born in 1863 at Murree, British India (now Pakistan), to a British military family, being the brother of Major-General George Younghusband and the second son of Major-General John W. Younghusband[1] and his wife Clara Jane Shaw. Clara's brother, Robert Shaw, was a noted explorer of Central Asia. His uncle Lieutenant-General Charles Younghusband CB FRS, was a British Army officer and meteorologist.

As an infant, Francis was taken to live in England by his mother. When Clara returned to India in 1867 she left her son in the care of two austere and strictly religious aunts. In 1870 his mother and father returned to England and reunited the family. In 1876 at age thirteen, Francis entered Clifton College, Bristol. In 1881 he entered the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, and was commissioned as a subaltern in the 1st King's Dragoon Guards in 1882.[1]

Military career

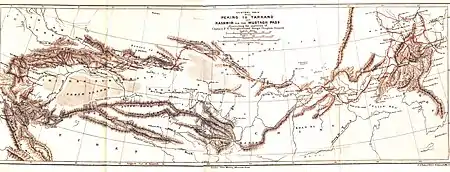

Having read General MacGregor's book Defence of India he could have justifiably called himself an expert on the "Great Game" of espionage that was unfolding on the Steppes of Asia.[3] In 1886–1887, on leave from his regiment, Younghusband made an expedition across Asia though still a young officer. After sailing to China his party set out, with Colonel Mark Bell's permission, to cross 1200 miles of desert with the ostensible authority to survey the geography; but in reality the purposes were to ascertain the strength of the Russian physical threats to the Raj. Departing Peking with a senior colleague, Henry E. M. James (on leave from his Indian Civil Service position) and a young British consular officer from Newchwang, Harry English Fulford, on 4 April 1887, Lieut Younghusband explored Manchuria, visiting the frontier areas of Chinese settlement in the region of the Changbai Mountains.[4][5]

On arrival in India he was granted three months' leave by the Commander-in-Chief Field Marshal Lord Roberts; the scientific results of this travel would prove vital information to the Royal Geographical Society. Younghusband had already carried out numerous scientific observations in particular, showing that the Changbai Mountains's highest peak, Baekdu Mountain, is only around 8,000 feet tall, even though the travellers' British maps showed [nonexistent] snow-capped peaks 10,000-12,000 ft tall in the area.[6] Fulford provided the travellers with language and cultural expertise.[7] Younghusband crossed the most inhospitable terrain in the world to the Himalayas before being ordered to make his way home. Parting with his British companions, he crossed the Taklamakan Desert to Chinese Turkestan, and pioneered a route from Kashgar to India through the uncharted Mustagh Pass.[4] He reported to the Viceroy, Lord Dufferin, his crossing through the Karakoram Range, the Hindu Kush, the Pamirs and where the range converged with the Himalayas; the nexus of three great empires. In the 1880s the region of the Upper Oxus was still largely unmapped. For this achievement, aged still only 24, he was elected the youngest member of the Royal Geographical Society and received the society's 1890 Patron's Gold Medal.

In 1889, he made captain, and was dispatched with a small escort of Gurkha soldiers to investigate an uncharted region north of Ladakh, where raiders from Hunza had disrupted trade between Yarkand and India the previous year.[8] Whilst encamped in the valley of the Yarkand River, Younghusband received a messenger at his camp, inviting him to dinner with Captain Bronislav Grombchevsky, his Russian counterpart in "The Great Game". Younghusband accepted the invitation to Grombchevsky's camp, and after dinner the two rivals talked into the night, sharing brandy and vodka, and discussing the possibility of a Russian invasion of British India. Grombchevsky impressed Younghusband with the horsemanship skills of his Cossack escort, and Younghusband impressed Grombchevsky with the rifle drill of his Gurkhas.[9] After their meeting in this remote frontier region, Grombchevsky resumed his expedition in the direction of Tibet and Younghusband continued his exploration of the Karakoram.

Political career

Younghusband received a telegram from Simla, to attend the Intelligence Department (ID) to be interviewed by Foreign Secretary Sir Mortimer Durand, transferred to the Indian Political Service. He served as a political officer on secondment from the British Army. He refused a request to visit Lhasa as an interpreter, disguised as a Yarkandi trader, a cover not guaranteed to fool the Russians, after Andrew Dalgleish, a Scots merchant, had been brutally hacked to death. Younghusband was accompanied by a Gurkha escort, celebrated for their ferocity in combat. The Forward policy was circumscribed by a legal offer to all travellers of a peaceable security crossing borders. Departure from Leh on 8 August 1889 on the caravan route took them up the mountain pass of Shimshal towards Hunza, his aim being to restore the tea trade to Xinjiang and prevent any further raids into Kashmir. Colonel Durand from Gilgit joined him. Younghusband probed the villages to gauge the reception: calculating it was a den of thieves, they ascended the steep ravine. The Hunza was barred to them, a trap was sprung; the parley terms took him inside to negotiate. The nervous reception over, they were all relieved to find safety; Younghusband wanted to know who was waylaying innocent civilian traders, and why. The ruler, Safdar Ali extended a letter of welcome to his Kashmiri kingdom; the British investigated from whence came the Russian infiltrators under Agent Gromchevsky. Further south at Ladakh, he kept close watch on their movements. Reluctantly, Younghusband dined with the Cossack leaders, who divulged the secrets of their common rivalry. Gromchevsky explained that the Raj had invited enmity for meddling in the Black Sea ports. The Russian displayed little grasp of strategy, but basic raw courage; he betrayed the confidence of Abdul Rahman as no friend to the British. Younghusband tentatively concluded that their possessions at Bokhara and Samarkand were vulnerable. Having drunk large quantities of vodka and brandy, the Cossacks presented arms in cordial salute and they parted in peace. Woefully unprepared for winter, the British garrison at Ladakh refused them entry.

Younghusband finally arrived at Gulmit to a 13-gun salute. In khaki, the envoy greeted Safdar Ali at the marquee on the Karakoram Highway, the men of Hunza kneeling at their ruler's feet. This was colonial diplomacy, based on protocol and etiquette, but Younghusband had not come for merely trivial discussions. Reinforced by Durand's troops, Younghusband's arguments were to prevent the criminal looting, murder and highway robbery. Impervious to reason though Safdar Ali was, Younghusband was not prepared to allow him to laugh at the Raj. A demonstration of firepower "caused quite a sensation", he wrote in his diaries. The British major was disdainful, but content when he left on 23 November to return to India, which he reached by Christmas.

In 1890, Younghusband was sent on a mission to Chinese Turkestan, accompanied by George Macartney as interpreter. He spent the winter in Kashgar, where he left Macartney as British consul.[10] Younghusband wanted to investigate the Pamir Gap, a possible Russian entry route to India, but he had had to ensure that the Chinese at Kashgar were sorted out, to prevent a tripartite attempt by the Hunza clans. It was for this reason he recruited a Mandarin interpreter, junior officer George Macartney, to accompany his missions into the frozen mountains. They wintered in Kashgar as a listening post, meeting in conference with the Russian Nikolai Petrovsky, who had always resisted trade with Xinjiang (Sinkiang). The Russian agent was well-informed about British India, but proved unscrupulous. Believing he had succeeded, Younghusband did not reckon on Petrovsky's deal with the Taotai, the Chinese governor of Hunza.

In July 1891, they were still in the Pamirs when news reached them that the Russians intended to send troops "to note and report with the Chinese and Afghans". At Bozai Gumbaz in the Little Pamir on 12 August he encountered Cossack soldiers, who forced him to leave the area.[11] This was one of the incidents which provoked the Hunza-Nagar Campaign. The troop of 20 or so soldiers planted a flag on what they anticipated was unclaimed territory, 150 miles south of the Russian border. However, the British considered the area to be Afghan territory. Colonel Yonov, decorated with the Order of St George, approached his camp to announce that the area now belonged to the Tsar. Younghusband learnt that they had raided the Chitral territory; furthermore, they had penetrated the Darkot Pass into the Yasin Valley. They were joined by eager intelligence officer Lieutenant Davison, but the British were disabused by Ivanov of British sovereignty: Younghusband remained polite, maintained protocol but hospitable to the big Russian bear hug.

During his service in Kashmir, he wrote a book called Kashmir at the request of Edward Molyneux. Younghusband's descriptions went hand in glove with Molyneux's paintings of the valley. In the book, Younghusband declared his immense admiration of the natural beauty of Kashmir and its history. The Great Game, between Britain and Russia, continued beyond the start of the 20th century until officially ended by the 1907 Anglo-Russian Treaty. Younghusband, among other explorers such as Sven Hedin, Nikolay Przhevalsky, Shoqan Walikhanov and Sir Auriel Stein, had participated in earnest.[12] Rumours of Russian expansion into the Hindu Kush with a Russian presence in Tibet prompted the new Viceroy of India Lord Curzon to appoint Younghusband, by then a major, British commissioner to Tibet from 1902–1904.

Expedition to Tibet

In 1903, Curzon appointed Younghusband head of the Tibet Frontier Commission with John Claude White, political officer of Sikkim, and E. C. Wilton as deputy commissioners.[13] He subsequently led the 1903-04 British expedition to Tibet, whose putative aim was to settle disputes over the Sikkim-Tibet border, but by exceeding instructions from London, the expedition controversially became a de facto invasion of Tibet.[14]

About 100 miles (160 km) inside Tibet, on the way to Gyantse, thence to the capital of Lhasa, a confrontation outside the hamlet of Guru led to a victory by the expedition over 600-700 Tibetan militia, largely monks.[15] Some estimates of Tibetan casualties are far higher; inciting other conflicts,[16] Younghusband's well-trained troops were armed with rifles and machine guns, confronting disorganized monks wielding hoes, swords, and flintlocks. Some accounts estimated that more than 5,000 Tibetans were killed during the campaign, while the total number of British casualties was about five.

The British force was supported by King Ugyen Wangchuck of Bhutan, who was knighted in return for his services. The incident, portrayed by Chinese sources as a "massacre", embarrassed the British Government, which desired good relations with China for the sake of the coastal Chinese trade. Accordingly, the British repudiated the treaty known as the Treaty of Lhasa that Younghusband's services had obtained.

In 1891, Younghusband received the Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire, which was upgraded to Knight Commander in 1904;[1] and in 1917, he was awarded the honour of Knight Commander of the Order of the Star of India. He was also awarded the Kaisar-I-Hind Medal (gold) in 1901[1] and the Gold Medal of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society in 1905.[17]

In 1906, Younghusband settled in Kashmir as the British representative before returning to Britain, where he was an active member of many clubs and societies. In 1908, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel. During the First World War, his patriotic Fight for Right campaign commissioned the song "Jerusalem".

Himalaya and mountaineering

In 1889, Younghusband reached base of Turkestan La (North) from north, and he noted that this was a long glacier and a major Central Asian dividing range.[18]

In 1919, Younghusband was elected President of the Royal Geographical Society, and two years later became Chairman of the Mount Everest Committee which was set up to coordinate the initial 1921 British Reconnaissance Expedition to Mount Everest.[19] He actively encouraged the accomplished climber George Mallory to attempt the first ascent of Mount Everest, and they followed the same initial route as the earlier Tibet Mission. Younghusband remained Chairman through the subsequent 1922 and 1924 British Expeditions.

In 1938, Younghusband encouraged Ernst Schäfer, who was about to lead a German expedition to "sneak over the border" when faced with British intransigence towards Schäfer's efforts to reach Tibet.[20]

Personal life

In 1897 Younghusband married Helen Augusta Magniac, the daughter of Charles Magniac, MP. Augusta's brother, Vernon, served as Younghusband's private secretary during the expedition to Tibet.[21] The Younghusbands had a son who died in infancy, and a daughter, Eileen Younghusband (1902–1981), who became a prominent social worker.[22]

From 1921 to 1937 the couple lived at Westerham, Kent, but Helen did not accompany her husband on his travels. In July 1942 Younghusband suffered a stroke after addressing a meeting of the World Congress of Faiths in Birmingham. He died of cardiac failure on 31 July 1942 at Madeline Lees' home Post Green House, at Lytchett Minster, Dorset.[23] He was buried in the village churchyard.[22]

Spiritual life

Biographer Patrick French described Younghusband's religious belief as one who was

brought up an Evangelical Christian, read his way into Tolstoyan simplicity, experienced a revelatory vision in the mountains of Tibet, toyed with telepathy in Kashmir, proposed a new faith based on virile racial theory, then transformed it into what Bertrand Russell called 'a religion of atheism.'[24]

Ultimately he became a spiritualist and "premature hippie" who "had great faith in the power of cosmic rays, and claimed that there are extraterrestrials with translucent flesh on the planet Altair."[25]

During his 1904 retreat from Tibet, Younghusband had a mystical experience which suffused him with "love for the whole world" and convinced him that "men at heart are divine."[26] This conviction was tinged with regret for the invasion of Tibet, and eventually, in 1936, profound religious convictions invited a founder's address to the World Congress of Faiths (in imitation of the World Parliament of Religions). Younghusband published a number of books with what one might call New Age themes, with titles like The Gleam: Being an account of the life of Nija Svabhava, pseud. (1923); Mother World (in Travail for the Christ that is to be) (1924); and Life in the Stars: An Exposition of the View that on some Planets of some Stars exist Beings higher than Ourselves, and on one a World-Leader, the Supreme Embodiment of the Eternal Spirit which animates the Whole (1927). The last drew the admiration of Lord Baden-Powell, the Boy Scouts founder.[27] Key concepts consisted of the central belief that would come to be known as the Gaia hypothesis, pantheism, and a Christlike "world leader" living on the planet "Altair" (or "Stellair"), exploring the theology of spiritualism, and guidance by means of telepathy.

In his book Within: Thoughts During Convalescence (1912), Younghusband stated:

We are giving up the idea that the Kingdom of God is in Heaven, and we are finding that the Kingdom of God is within us. We are relinquishing the old idea of an external God, above, apart, and separate from ourselves; and we are taking on the new idea of an internal spirit working within us - a constraining, immanent influence, a vital, propelling impulse vibrating through us all, expressing itself and fulfilling its purpose through us, and uniting us together in one vast spiritual unity.[28]

Younghusband took interest in Eastern philosophy and Theosophy and dismissed the idea of an anthropomorphic god.[29] Taking influence from Henri Bergson's Creative Evolution, he proposed purpose in the cosmos through a creative life force. Younghusband's philosophy of cosmic spiritual evolution was outlined in his books Life in the Stars (1927) and The Living Universe (1933).[29] In the latter book he proposed the idea that the universe is a living organism. Younghusband held the view that spiritual forces in the universe are directing evolution and producing life and intelligence on many different planets.[29] Younghusband's ideas were dismissed by scientists and few took his ideas seriously. He founded the World Congress of Faiths to promote dialogue between different religions.[29]

Younghusband allegedly believed in free love ("freedom to unite when and how a man and a woman please"), marriage laws examined as a matter of "outdated custom."[30] One of Younghusband's domestic servants, Gladys Aylward, became a Christian missionary in China.

Fictional portrayal

The Ingrid Bergman film The Inn of the Sixth Happiness (1958) is based on Gladys Aylward's life, with Ronald Squire portraying Younghusband.[31]

Works

Younghusband wrote 26 books in all between 1885 and 1942. Subjects ranged from Asian events, exploration, mountaineering, philosophy, spirituality, politics and more.

- Confidential Report of a Mission to the Northern Frontier of Kashmir in 1889 (Calcutta, 1890).

- The Relief of Chitral (1895) (co-authored with his brother George John Younghusband)

- South Africa of Today (1896)

- The Heart of a Continent (1896) The heart of a continent: vol.1

- . The Empire and the century. London: John Murray. 1905. pp. 599–620.

- Kashmir (1909)

- India and Tibet: a history of the relations which have subsisted between the two countries from the time of Warren Hastings to 1910; with a particular account of the mission to Lhasa of 1904. London: John Murray. 1910.

- Within: Thoughts During Convalescence (1912)

- Mutual Influence: A Re-View of Religion (1915)

- The Sense of Community (1916)

- The Gleam (1923)

- Modern Mystics (1923) (ISBN 1-4179-8003-6, reprint 2004)

- Mother World in Travail for the Christ that is to be (1924)

- Wonders of the Himalayas (1924)[32]

- The Epic of Mount Everest (1926) (ISBN 0-330-48285-8, reprint 2001).

- Life in the Stars (1927)

- The Light of Experience (1927)[32]

- Dawn in India (1930)

- The Living Universe (1933)

- The Mystery of Nature in Frances Mason. The Great Design: Order and Progress in Nature (1934)

- The Sum of Things (1939)

- Vital Religion (1940)

References

- C. Hayavando Rao, ed. (1915). The Indian Biographical Dictionary. Madras: Pillar & Co. pp. 470–71. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- James 1887, pp. 235–238

- General Sir C MacGregor, The Defence of India, (Simla, 1884)

- Younghusband, Francis E. (1896). The Heart of a Continent, pp. 58-290. John Murray, London. Facsimile reprint: (2005) Elbiron Classics.

- James, Sir Henry Evan Murchison (1888), The Long White Mountain, or, A journey in Manchuria: with some account of the history, people, administration and religion of that country, Longmans, Green, and Co.

- [[#CITEREF|]], pp. 254,262)

- [[#CITEREF|]], pp. 125,217)

- The Heart of a Continent, pp. 186ff

- The Heart of a Continent, pp. 234ff

- Dictionary of National Biography Sir George Macartney

- Riddick, John (2006). The history of British India. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-313-32280-8.

- David Nalle (June 2000). "Book Review – Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia". Middle East Policy. Washington DC: Blackwell. VII (3). ISSN 1061-1924. Archived from the original on 1 June 2006.

- Patrick French (2011). Younghusband: The Last Great Imperial Adventurer. Penguin Books Limited. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-14-196430-0.

- "Tibetans' fight against British invasion". En.Tibet.cn – China Tibet Information Center. Archived from the original on 3 November 2007. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- Morris, James: Farewell the Trumpets (Faber & Faber, 1979), p.102.

- Nick Heil (2008). Dark Summit: The Extraordinary True Story of One of the Deadliest Seasons on Everest. Virgin Books Ltd. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-7535-1359-0.

- "Scottish Geographical Medal". Royal Scottish Geographical Society. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- 1999, Saga of Siachen, The Himalayan Journal, Vol.55.

- "Text of The Epic of Mount Everest, Sir Francis Younghusband". Archived from the original on 26 May 2008. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- Hale, Christopher. Himmler's Crusade (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2003) pp. 149-151

- Fleming, Peter (2012). Bayonets to Lhasa - the British invasion of Tibet. Tauris Parke, London. ISBN 9780857731432.

- Dictionary of National Biography

- Anon. 1942 Obituary: Sir Francis Edward Younghusband. Geographical Review 32(4):681

- French, p.313.

- French, p. xx

- quoted in French, p.252.

- French, p. 321

- Drake, Durant (1919). "Seekers After God" (PDF). The Harvard Theological Review. 12 (1): 67–83.

- Bowler, Peter J. (2001). Reconciling Science and Religion: The Debate in Early-Twentieth-Century Britain. University of Chicago Press. pp. 391-393. ISBN 0-226-06858-7

- French, p. 283

- French., p. 364

- Hopkirk, op cit.

- Secondary sources

- Allen, Charles (2004). Duel in the Snows: The True Story of the Younghusband Mission to Lhasa. London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-5427-6.

- Broadbent, Tom (2005). On Younghusband's Path: Peking to Pindi. ISBN 0-9548542-2-5.

- Candler, Edmund (1905). The Unveiling of Lhasa. Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd.

- Carrington, Michael (2003). "Officers Gentlemen and Thieves: The Looting of Monasteries during the 1903/4 Younghusband Mission to Tibet". Modern Asian Studies. 37, 1: 81–109. doi:10.1017/S0026749X03001033.

- Fleming, Peter (1986). Bayonets to Lhasa. ISBN 978-0195838626.

- French, Patrick (1997). Younghusband: The Last Great Imperial Adventurer. ISBN 0-00-637601-0.

- Hopkirk, Peter (1990). The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia. pp. 447–482. ISBN 1-56836-022-3.

- Mehra, P. (1968). The Younghusband Expedition.

- Meyer, Karl E.; Brysac, Shareen Blair (25 October 1999). Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia. Basic Books. ISBN 978-1-58243-106-2.

- Seaver, George (1952). Francis Younghusband: Explorer and Mystic.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Francis Younghusband |

- Halkias, Giorgos, The 1904 Younghusband's Expedition to Tibet, ELINEPA, 2004

- Description of rare Younghusband photograph collection held by the Royal Geographical Society of South Australia

- Works by Francis Younghusband at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Francis Younghusband at Internet Archive

- Portraits of Francis Younghusband at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- "Archival material relating to Francis Younghusband". UK National Archives.

- World Congress of Faiths' History

- Royal Geographic Society photograph of Younghusband's Mission to Tibet

- 1st King's Dragoon Guards (regiments.org)

- The heart of nature (1921)

- India and Tibet (1910)