Gajah Mada

Gajah Mada (ꦒꦗꦃꦩꦢ) (c. 1290 – c. 1364) was, according to Old Javanese manuscripts, poems and mythology, a powerful military leader and Mahapatih or (equal to) Prime Minister of the Javanese empire of Majapahit, credited with bringing the empire to its peak of glory.[2]:234,239 He delivered an oath called Sumpah Palapa, in which he vowed to live ascetic (by not consuming food containing spices) until he had conquered all of the Southeast Asian archipelago of Nusantara for Majapahit.[3] In modern Indonesia, he serves as an important national hero,[4] a symbol of patriotism and national unity. During his reign the Hindu epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, became ingrained in the culture and worldview of the Javanese through the performing arts of wayang kulit (“leather puppets”).[5]

Gajah Mada | |

|---|---|

Illustration of Gajah Mada, based on earlier, M. Yamin's illustration | |

| Mahapatih of Majapahit Empire | |

| In office 1329 – c.1364 | |

| Monarch | Jayanegara Tribhuwana Wijayatunggadewi Hayam Wuruk |

| Personal details | |

| Died | c. 1364 |

| Religion | Buddhism[1] |

This account of his life, political career and administration was taken from several sources. Mainly Pararaton ("The Book of Kings"), the Nagarakretagama (a Javanese language epic poem dating from the 14th century), and inscriptions dating from the late 13th and early 14th century.

The popular depiction of Gajah Mada in the media is actually an imagination of M. Yamin, in his book entitled "Gajah Mada: Pahlawan Persatuan Nusantara", first published in 1945. There is also another illustration about the figure of Gajah Mada, different from the M. Yamin's, which is the result of research at the University of Indonesia by archaeologist Agus Aris Munandar. He illustrated Gajah Mada as similar to Bima in wayang shadow puppet show, which has a transverse mustache.[6] He is mostly shown bare-chested, wearing a sarong, and using a weapon in the form of a kris. Historical sources, in fact, does not support this. A Sundanese patih explained (written in the kidung Sundayana), that Gajah Mada wore golden embossed karambalangan (breastplate), armed with gold-layered spear, and with a shield full of diamond decoration.[7][8][9]

Rise to power

Not much is known about Gajah Mada's early life, but he was born into an ordinary family. Some of the first accounts mention his career as commander of the Bhayangkara, an elite royal guard for the Majapahit king and royal family.

When Rakrian Kuti, one of the officials in Majapahit, rebelled against the Majapahit king Jayanegara (ruled 1309–1328) in 1321, Gajah Mada and the mahapatih Arya Tadah helped the king and his family to escape the capital city of Trowulan. Later Gajah Mada helped the king return to the capital and crush the rebellion. Seven years later, Jayanegara was murdered by the court physician Rakrian Tanca, one of Rakrian Kuti's aides.

Another version suggested that Jayanagara was assassinated by Gajah Mada in 1328. Jayanagara was overly protective of his two half sisters, born from Kertarajasa's youngest queen, Dyah Dewi Gayatri. Complaints by the two young princesses led to the intervention of Gajah Mada. His solution was to arrange for a surgeon to murder the king while pretending to perform a surgery.

Jayanegara was immediately succeeded by his half-sister Tribhuwana Wijayatunggadewi (ruled 1328–1350). It was under her leadership that Gajah Mada was appointed mahapatih (Prime Minister) in 1329, after the retirement of Arya Tadah.

As mahapatih under Tribhuwana Tunggadewi, Gajah Mada went on to crush another rebellion by Sadeng and Keta in 1331.

It was during Gajah Mada's reign as mahapatih, around the year 1345, that the famous Muslim traveller, Ibn Battuta visited Sumatera.

The Palapa Oath and Empire Expansion

It is said that it was during his appointment as mahapatih under queen Tribhuwanatunggadewi that Gajah Mada took his famous oath, the Palapa Oath or Sumpah Palapa. The telling of the oath is described in the Pararaton (Book of Kings), an account on Javanese history that dates from the 15th or 16th century:

“Sira Gajah Mada pepatih amungkubumi tan ayun amukita palapa, sira Gajah Mada : Lamun huwus kalah nusantara Ingsun amukti palapa, lamun kalah ring Gurun, ring Seram, Tanjungpura, ring Haru, ring Pahang, Dompo, ring Bali, Sunda, Palembang, Temasek, samana ingsun amukti palapa “

"Gajah Mada, the prime minister, said he will not taste any spice. Said Gajah Mada : If Nusantara (Nusantara= Nusa antara= external territories) are lost, I will not taste "palapa" ("fruits and/or spices"). I will not if the domain of Gurun, domain of Seram, domain of Tanjungpura, domain of Haru, Pahang, Dompo, domain of Bali, Sunda, Palembang, Tumasik (Singapore), in which case I will never taste any spice."

While often interpreted literally to mean that Gajah Mada would not allow his food to be spiced (palapa is the prose combination of pala apa= any fruits/spices) the oath is sometimes interpreted to mean that Gajah Mada would abstain from all earthly pleasures until he conquered the entire known archipelago for Majapahit.

Even his closest friends were at first doubtful of his oath, but Gajah Mada kept pursuing his dream to unify Nusantara under the glory of Majapahit. Soon he conquered the surrounding territory of Bedahulu (Bali) and Lombok (1343). He then sent the navy westward to attack the remnants of the thalassocratic kingdom of Sriwijaya in Palembang. There he installed Adityawarman, a Majapahit prince as vassal ruler of the Minangkabau in West Sumatra.

He then conquered the first Islamic sultanate in Southeast Asia, Samudra Pasai, and another state in Svarnadvipa (Sumatra). Gajah Mada also conquered Bintan, Tumasik (Singapore), Melayu (now known as Jambi), and Kalimantan.

At the resignation of the queen, Tribuwanatunggadewi, her son, Hayam Wuruk (ruled 1350–1389) became king. Gajah Mada retained his position as mahapatih (Prime Minister) under the new king and continued his military campaign by expanding eastward into Logajah, Gurun, Seram, Hutankadali, Sasak, Buton, Banggai, Kunir, Galiyan, Salayar, Sumba, Muar (Saparua), Solor, Bima, Wandan (Banda), Ambon, Timor, and Dompo.

He thus effectively brought the modern Indonesian archipelago under Majapahits's control, which spanned not only the territory of today's Indonesia, but also that of Temasek (old name of Singapore), the states comprising modern-day Malaysia, Brunei, the southern Philippines and East Timor.

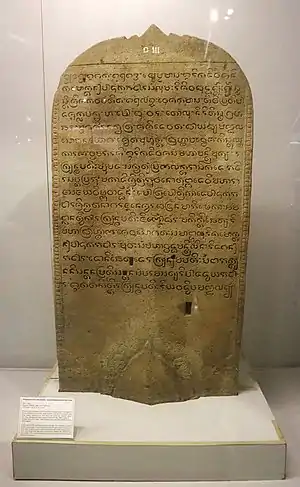

According to Gajah Mada inscription, dated 1273 Saka (1351 CE), on the month of Wesakha, Sang Mahamantrimukya Rakryan Mapatih Mpu Mada (Gajah Mada) commanded, created and inaugurated a sacred building of caitya, dedicated for the late Paduka Bhatara Sang Lumah ri Siwa Buddha (King Kertanegara) that was died in 1214 Saka (1292 CE) on the month Jyesta. The inscription was discovered in Singosari subdistrict, Malang, East Java, and was written in Old Javanese script and language. The caitya or temple mentioned in this inscription is highly possible Singhasari temple. The special reverence to King Kertanegara of Singhasari demonstrated by Gajah Mada suggests that the Prime Minister honoured the late king tremendously, and possibly the two are related. Some historian suggests that possibly Kertanegara was Gajah Mada's grandfather.[10]

The Bubat Incident

.jpg.webp)

In 1357, the only remaining state refusing to acknowledge Majapahit's hegemony was Sunda, in West Java, bordering the Majapahit Empire. King Hayam Wuruk intended to marry Dyah Pitaloka Citraresmi, a princess of Sunda and the daughter of Sunda's king. Gajah Mada was given the task to go to the Bubat square in the northern part of Trowulan to welcome the princess as she arrived with her father and escort to Majapahit palace.

Gajah Mada took this opportunity to demand Sunda submission to Majapahit rule. While the Sunda King thought that the royal marriage was a sign of a new alliance between Sunda and Majapahit, Gajah Mada thought otherwise. He stated that the Princess of Sunda was not to be hailed as the new queen consort of Majapahit, but merely as a concubine, as a sign of submission of Sunda to Majapahit. This misunderstanding led to embarrassment and hostility, which quickly rose into a skirmish and then the full scale Battle of Bubat. The Sunda King with all of his guards as well as the royal party were overwhelmed by Majapahit troops and subsequently killed in the field of Bubat. Tradition mentioned that the heartbroken princess, Dyah Pitaloka Citraresmi, committed suicide.

Hayam Wuruk was deeply shocked by the tragedy. Majapahit courtiers, ministers and nobles blamed Gajah Mada for his recklessness, and the brutal consequences were not to the taste of the Majapahit royal family. Gajah Mada was promptly demoted and spent the rest of his days at the estate of Madakaripura in Probolinggo in East Java.

Death

Gajah Mada died in obscurity in 1364.[2]:240 King Hayam Wuruk considered the power Gajah Mada had accumulated during his time as mahapatih too much to handle for a single person. Therefore, the king split the responsibilities that had been Gajah Mada's, between four separate new mahamantri (equal to ministries), thereby probably increasing his own power. King Hayam Wuruk, who is said to have been a wise leader, was able to maintain the hegemony of Majapahit in the region, gained during Gajah Mada's service. However Majapahit slowly fell into decline after the death of Hayam Wuruk.

Legacy

His reign helped further Indianisation of Javanese culture through the spread of Hinduism and sanskritization.[2][5]

The Blahbatuh royal house in Gianyar, Bali, has been performing Gajah Mada's mask dance drama ritually for the past 600 years. The mask of Gajah Mada has been protected and brought to life every couple of years to unite and harmonize the world, this sacred ritual was intended to bring peace to Bali.[11]

Gajah Mada's legacy is important for Indonesian Nationalism, and invoked by the Indonesian Nationalist movement in the early 20th century. The Nationalists prior to the Japanese invasion, notably Sukarno and Mohammad Yamin, often cited Gajah Mada's oath and Nagarakretagama as the inspiration and a historical proof of Indonesian past greatness — that Indonesians could unite, despite vast territory and various cultures. The Gajah Mada campaign that united the far flung islands within the Indonesian archipelago under Majapahit suzerainty, was used by Indonesian nationalists to argue that an ancient form of unity had existed prior to Dutch colonialism.[12] Thus, Gajah Mada was a great inspiration during the Indonesian National Revolution for independence from Dutch colonization.

In 1942, only 230 Indonesian natives held a tertiary education. The Republicans sought to mend the Dutch apathy and established the first state university, which freely admitted native pribumi Indonesians. Universitas Gadjah Mada, in Yogyakarta is named in honour of Gajah Mada and was completed in 1945, and had the honour of being the first Medicine Faculty freely open to natives.[13][14][15]

Launched in 9 July 1976, Indonesia's first telecommunication satellite was called Satelit Palapa signifying its role in uniting the vast archipelagic nation.

The Army Military Police Corps of the Indonesian Army has honored Gajah Mada as their unit symbol. The symbol of the Army MP corps also has the picture of Gajah Mada.

Many cities in Indonesia have streets named after Gajah Mada, such as Jalan Gajah Mada and Jalan Hayam Wuruk. There is a brand of badminton shuttlecock named after him as well.

In popular culture

- Gajah Mada appeared in the expansion pack Brave New World for the PC video game Sid Meier's Civilization V as the leader of the Indonesian civilization.

- Gajah Mada has a campaign for the Malay civilization in the Age of Empires II expansion pack, Rise of the Rajas. The campaign revolves around the establishment of the Majapahit empire with the Mongol invasion, the conquest of the archipelago after the Palapa Oath and the Bubat Tragedy that led to his downfall. He also made appearance in the Age of Empires II Definitive Edition.

- Gajah Mada appears centrally in a pentalogy of novels by Langit Kresna Hariadi, which were published between 2004 and 2007.[16]

- Gajah Mada is also mentioned as Prime Minister of Majapahit Empire in the anime Joukamachi no Dandelion.

See also

Notes

- Yunanto Wiji Utomo (22 June 2017). "Agama Gajah Mada dan Majapahit yang Sebenarnya Akhirnya Diungkap". Kompas.

- Cœdès, George (1968). The Indianized states of Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824803681.

- Pradipta, Budya (2004). "Sumpah Palapa Cikal Bakal Gagasan NKRI" (PDF) (in Indonesian). Perpustakaan Nasional Republik Indonesia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 February 2009.

- "Majapahit Story : The History of Gajah Mada". Memory of Majapahit. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Mark Juergensmeyer and Wade Clark Roof, 2012, Encyclopedia of Global Religion, Volume 1, Page 557.

- Darmajati, Danu (29 December 2015). "Sejarawan: Wajah Gajah Mada Karya M Yamin Pertama Ada Tahun 1945". Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- Berg, Kindung Sundāyana (Kidung Sunda C), Soerakarta, Drukkerij “De Bliksem”, 1928.

- Nugroho, Irawan Djoko (2011). Majapahit Peradaban Maritim. Suluh Nuswantara Bakti. ISBN 9786029346008.

- Nugroho, Irawan Djoko (6 August 2018). "The Golden Armor of Gajah Mada". Nusantara Review. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- "Siapa Sebenarnya Kakek Gajah Mada?". Historia - Majalah Sejarah Populer Pertama di Indonesia (in Indonesian). Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- Sertori, Trisha (16 June 2010). "The mask of unity". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- Wood, Michael. "The Borderlands of Southeast Asia Chapter 2: Archaeology, National Histories, and National Borders in Southeast Asia" (PDF): 36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2015. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Stephen Lock, John M. Last, George Dunea. The Oxford illustrated companion to medicine Oxford Companions Series-Oxford reference online. Oxford University Press US: 2001. ISBN 0-19-262950-6. 891 pages: pp. 765

- James J. F. Forest, Philip G. Altbach. Volume 18 of Springer international handbooks of education: International handbook of higher education, Volume 1. Springer: 2006. ISBN 1-4020-4011-3. 1102 pages. pp772

- R. B. Cribb, Audrey Kahin. Volume 51 of Historical dictionaries of Asia, Oceania, and the Middle East: Historical dictionary of Indonesia. Scarecrow Press: 2004. ISBN 978-0-8108-4935-8. 583 pages. 133

- Langit Kresna Hariadi at Goodreads

_last_quarter_of_the_10th%E2%80%93first_half_of_the_11th_century.jpg.webp)