Nusantara

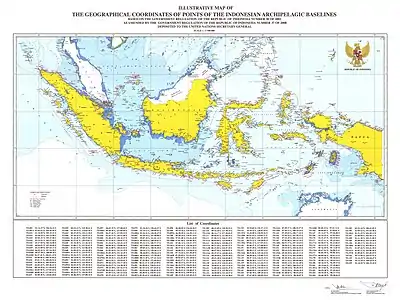

Nusantara is the Indonesian name of Maritime Southeast Asia (or parts of it). It is an Old Javanese term which literally means "outer islands".[1] In Indonesia, it is generally taken to mean the Indonesian Archipelago.[2][3]

The word Nusantara is taken from an oath by Gajah Mada in 1336, as written in the Old Javanese Pararaton and Nagarakretagama.[4] Gajah Mada was a powerful military leader and prime minister of Majapahit credited with bringing the empire to its peak of glory. Gajah Mada delivered an oath called Sumpah Palapa, in which he vowed not to eat any food containing spices until he had conquered all of Nusantara under the glory of Majapahit.

The concept of Nusantara as a unified region was not invented by Gajah Mada in 1336. Earlier in 1275, the term Cakravala Mandala Dvipantara is used to describe the Southeast Asian archipelago by Kertanegara of Singhasari.[5] Dvipantara is a Sanskrit word for the "islands in between", making it a synonym to Nusantara as both dvipa and nusa mean "island". Kertanegara envisioned the union of Southeast Asian maritime kingdoms and polities under Singhasari as a bulwark against the rise of the expansionist Mongol Yuan dynasty in mainland China.

Nusantara in modern language usage includes Malay-related cultural and linguistic lands, namely, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Southern Thailand, the Philippines, Brunei, East Timor and Taiwan, while excluding Papua New Guinea."[6]

Ancient concepts

Etymology

Nusantara is an Old Javanese word which appears in the Pararaton manuscript. In Javanese, Nusantara is derived from nūsa 'island' and antara, 'between'. It means "outer islands" or "other islands" (in the sense of "islands beyond Java in between the Indian and Pacific Oceans"), referring to the islands outside of Java under hegemony of the Majapahit Empire. The term is commonly erroneously translated as "archipelago" in modern times.[7] Based on the Majapahit concept of state, the monarch had power over three areas:

- Negara Agung, or the Grand State – the core realm of the kingdom where Majapahit formed before becoming an empire. This included the capital city and the surrounding areas where the king effectively exercised his government: the area in and around royal capital of Trowulan, port of Canggu and sections of Brantas River valley near the capital, as well as the mountainous areas south and southwest of the capital, all the way to the Pananggungan and Arjuno-Welirang peaks. The Brantas river valley corridor, connecting the Majapahit Trowulan area to Canggu and the estuarine areas in Kahuripan (Sidoarjo) and Hujung Galuh (Surabaya), is also considered to be part of Negara Agung.

- Mancanegara, the areas surrounding Negara Agung – this traditionally referred to the Majapahit provinces of East and Central Java ruled by the Bhres (dukes), the king's close relatives. This included the rest of Java as well as Madura and Bali. These areas were directly influenced by Majapahit court culture and obliged to pay annual tributes; their rulers might have been directly related to, allied with, and/or intermarried with the Majapahit royal family. Majapahit officials and officers were stationed in these places to regulate their foreign trade activities and collect taxes, but beyond this mancanegara provinces enjoyed substantial autonomy in internal affairs. In later periods, overseas provinces which had adopted Javanese culture or possessed significant trading importance were also considered mancanegara. The ruler of these provinces was either a willing vassal of the Majapahit king or a regent appointed by the king to rule the region. These realms included Dharmasraya, Pagaruyung, Lampung and Palembang in Sumatra.

- Nusantara, areas which did not reflect Javanese culture, but were included as colonies which had to pay annual tribute. This included the vassal kingdoms and colonies in Malay peninsula, Borneo, Lesser Sunda Islands, Sulawesi, Maluku, and Sulu archipelago. These regions enjoyed substantial autonomy and internal freedom, and Majapahit officials and military officers were not necessarily stationed there; however, any challenges to Majapahit oversight might have drawn a severe response.

Nusantara concept in the 20th century

In 1920, Ernest Francois Eugene Douwes Dekker (1879–1950), also known as Setiabudi, proposed Nusantara as a name for the independent country of Indonesia which did not contain any words etymologically related to the name of India or the Indies.[8] This is the first instance of the term Nusantara appearing after it had been written into Pararaton manuscript.

The definition of Nusantara introduced by Setiabudi is different from the 14th century definition of the term. During the Majapahit era, Nusantara described vassal areas that had been conquered. Setiabudi defined Nusantara as all the Indonesian regions from Sabang to Merauke, without the aggressive connotations of its former imperial usage.

Modern usage

Today in Indonesian, Nusantara is synonymous with the Indonesian archipelago or the national territory of Indonesia.[9] In this sense, the term Nusantara excludes Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, East Timor, and the Philippines. In 1967, it has transformed into the concept of Wawasan Nusantara or "archipelagic outlook", which regards the archipelagic realm of Indonesia, the islands and seas surrounding them, as a single unity of several aspects, mainly socio-cultural, language, as well as political, economic, security and defensive unity.[10]

Outside Indonesia

In Brunei, Malaysia, and Singapore the term is generally used to refer to the Malay archipelago or the Malay realm (Malay: Alam Melayu) which includes those countries.

In a more scholarly manner without national borders, Nusantara in a modern language usage "refers to the sphere of influence of the Malay cultural and linguistic islands that comprise Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, the southernmost part of Thailand, the Philippines, Brunei, East Timor and perhaps even Taiwan, but it does not involve the areas of Papua New Guinea."[6]

Nusantara studies

The Nusantara Society in Moscow conducts studies on the Nusantara region's history, culture, languages and politics.

See also

References

- Friend, T. (2003). Indonesian Destinies. Harvard University Press. p. 601. ISBN 0-674-01137-6.

- Echols, John M.; Shadily, Hassan (1989), Kamus Indonesia Inggris (An Indonesian-English Dictionary) (1st ed.), Jakarta: Gramedia, ISBN 979-403-756-7

- "Hasil Pencarian - KBBI Daring". kbbi.kemdikbud.go.id. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- Mpu, Prapañca; Robson, Stuart O. (1995). Deśawarṇana: (Nāgarakṛtāgama). KITLV. ISBN 978-90-6718-094-8.

- Wahyono Suroto Kusumoprojo (2009). Indonesia negara maritim. PT Mizan Publika. ISBN 978-979-3603-94-0.

- Evers, Hans-Dieter (2016). "Nusantara: History of a Concept". Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 89 (1): 3–14. doi:10.1353/ras.2016.0004. S2CID 163375995.

- Gaynor, Jennifer L. (2007). "Maritime Ideologies and Ethnic Anomalies". In Bentley, Jerry H.; Bridenthal, Renate; Wigen, Kären (eds.). Seascapes: Maritime Histories, Littoral Cultures, and Transoceanic Exchanges. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 59–65. ISBN 9780824830274.

- Vlekke, Bernard H.M. (1943), Nusantara: A History of the East Indian Archipelago (1st ed.), Netherlands: Ayer Co Pub, pp. 303–470, ISBN 978-0-405-09776-8

- "nusantara | Indonesian to English Translation - Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Indonesian Living Dictionary. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- Butcher, John G.; Elson, R. E. (24 March 2017). Sovereignty and the Sea: How Indonesia Became an Archipelagic State. NUS Press. ISBN 9789814722216.