German colonization of Africa

The German colonization of Africa took place during two distinct periods. In the 1680s, the Margraviate of Brandenburg, then leading the broader realm of Brandenburg-Prussia, pursued limited imperial efforts in West Africa. The Brandenburg African Company was chartered in 1682 and established two small settlements on the Gold Coast of what is today Ghana. Five years later, a treaty with the king of Arguin in Mauritania established a protectorate over that island, and Brandenburg occupied an abandoned fort originally constructed there by Portugal. Brandenburg — after 1701, the Kingdom of Prussia — pursued these colonial efforts until 1721, when Arguin was captured by the French and the Gold Coast settlements were sold to the Dutch Republic.

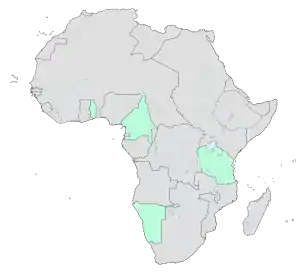

Over a century and a half later, the unified German Empire had emerged as a major world power. In 1884, pursuant to the Berlin Conference, colonies were officially established on the African west coast, often in areas already inhabited by German missionaries and merchants. The following year gunboats were dispatched to East Africa to contest the Sultan of Zanzibar's claims of sovereignty over the mainland in what is today Tanzania. Settlements in modern Guinea and Nigeria's Ondo State failed within a year; those in Cameroon, Namibia, Tanzania and Togo quickly grew into lucrative colonies. Together these four territories constituted Germany's African presence in the age of New Imperialism. They were invaded and largely occupied by the colonial forces of the Allied Powers during World War I, and in 1919 were transferred from German control by the League of Nations and divided between Belgium, France, Portugal, South Africa and the United Kingdom.

The six principal colonies of German Africa, along with native kingdoms and polities, were the legal precedents for the modern states of Burundi, Cameroon, Namibia, Rwanda, Tanzania and Togo. Parts of contemporary Chad, Gabon, Ghana, Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, the Central African Republic and the Republic of the Congo were also under the control of German Africa at various points during its existence.

German Desires for Tanganyika and Early Expansion

Germany decided to create a colony in East Africa under the leadership of Imperial Chancellor Otto von Bismarck in February 1885.[1] Germany had recently unified in 1871 and the rapid industrialization of their society required a steady stream of raw materials. The prospect of a colony in East Africa was too much to ignore; it was perfect for the continued economic stability and growth of Germany. Moreover, Bismarck was suspect of France and Great Britain’s true intentions in Africa and this only furthered his desire to create an East African colony. Soon after the agreement to create an East African colony was reached, the German Kaiser granted imperial protection to the possessions of the German East African Company, which had autonomy in the region.[2] In a way, this support by the German government completely changed the power and influence the German East African Company had. The company did not waste any time in dispatching eighteen expeditions to make treaties expanding its territories in East Africa, but these moves by the Germans stirred hostility in the region. When the company’s agents landed to take over seven coastal towns in the August of 1888, the tension finally escalated into violence.[3] Warriors flocked to a few of the coastal towns and gave the Germans two days to leave. In one instance, two Germans were killed in the town of Kilwa; German marines were eventually ordered in who cleared the town, killing every one they saw.[4] Resistance was seen all over German controlled Africa, but the German soldiers and officers came from the best army in the world, so the action of rebelling didn’t have much of a long-term impact. Resisting made the percentage of survival much less for Africans and brutality became synonymous with German imperialism in Africa.

The consolidation of German rule in Tanganyika

By 1898, the Germans controlled all of Tanganyika’s main population centers and lines of communication.[5] The next set of business for the Germans was to impose their rule over the small-scale societies further away from the caravan routes. This was done either by bargaining with African leaders or through warfare. After diplomacy concluded and the conflicts resulted in German victory, their regime used bands of gunmen to maintain authority over local leaders. Eventually, the main coastal towns, which were more settled, were converted into headquarters of administration districts, and civilian district officers were appointed.[6] Further inland, administration grew outwards from strategic garrisons but was transferred to civilian hands more slowly.[7] By 1914, Tanganyika was divided into 22 administrative districts, and only two of them were still ruled by soldiers.[8] The chief characteristic of German rule was the power and autonomy of the district officer; sheer lack of communication dictated this. Orders from the capital may have taken months to reach remote districts and a remote station could expect a visit from a senior official only once a decade. The district officer exercised full jurisdiction over ‘natives’, for although legislation specified the punishments he might impose, nothing defined the offences for which he might impose them.[9] The German rule of East Africa was solely based on force and German officials inspired great terror.

Two broad phases of district administration

When the Germans were in control of Tanganyika, two broad phases can summarize their rule. In the 1890’s their aims were military security and political control; to achieve this the Germans used a mixture of violence and alliances with African leaders.[10] These ‘local compromises’, as they may be called, had common characteristics. The Germans offered political and military support for their allies in exchange for the recognition of German authority, provision of labor and building materials, and the use of diplomacy instead of force in settling issues.[11] Moreover, the imposition of tax in 1898 initiated the transition to the second phase of administration whose chief characteristic was the collapse of the compromises made earlier in the decade.[12] The old compromises collapsed because the increase in German military strength made them less dependent on local allies and while earlier officers often welcomed their collaborators’ power, later ones suspected it. This led to a change from allied to adversarial relationships between some African leaders and the Germans. For example, Mtinginya of Usongo, a powerful Nyamwezi chief aided the Germans against Isike; but by 1901, he became a potential enemy and when he died a year or two later, his chiefdom was deliberately dismantled.[13] However, this was not what happened in other scenarios. Many of the old African collaborators did not necessarily lose power in this second stage of German administration, but to survive they had to adapt themselves and often reorganize their societies.[14]

Cotton

Cotton production in German East Africa was administered in a much different manner than in other areas of the continent. In some places throughout Africa, the colonial state only needed to provide seeds of encouragement as commercial agriculture was already well established. The ultimate goal of Europeans was to establish a market economy and that was done by compelling Africans into a labor pool. In German East Africa this was much harder to pursue as agriculture was less developed, and farmers sometimes needed to be coerced into producing certain crops.[15] The ‘cotton gospel’ was received less enthusiastically in Tanganyika than it was in British Uganda.[16] Perhaps this increased German brutality in East Africa, as Europeans would go to extreme measures to ensure their supply of raw materials.

In the initial stages of German control of East Africa, private German firms were given autonomy to run the establishment in East Africa. These German companies operated out of Bremen and Hamburg; the businesses were at the commercial and political frontier of the expanding colonial state.[17] However, this was quickly discovered to be inefficient as many of these firms went bankrupt because of mismanagement and African resistance.[18] Most companies eventually gave way to governmental authority by the beginning of the 1920s, but the German colonial empire had already collapsed by that point.

German Kamerun

The German consul, Gustav Nachtigal, declared Kamerun a protectorate of Germany on July 12, 1884.[19] A slow and cautious interest in Kamerun had been growing among German businessmen for thirty years before the finalization of Kamerun as a protectorate. The key to the initial German interest in Kamerun was German businessmen's desire for trade.[20] The Germans hoped to exploit the natural resources of the region and provide their country with a new market for manufactured goods; Kamerun was never considered to be a settler colony, as the climate was too hostile.[21] For a period of time, after the Germans declared Kamerun a protectorate, they only had a solidified position on the coast; the Germans had not been successful in opening trade routes in the interior, partly for geographical reasons. The forest aided the Africans in discouraging whites from extending trade activities beyond the coast. Nevertheless, the German interest in the interior continued, heightened by favorable reports from travelers such as Heinrich Barth in the 1850's; Gerhard Rohlfs in the 1860’s; and Gustav Nachtigal, from 1869 to 1873.[22] After the German navy cemented their control over the Kamerun coast, and further troop landings were made, the Germans were more inclined to move inland. The Germans were aided by the severe ethnic and political fragmentation of the inland groups. The extent of the forest prevented the coastal groups from uniting with the Grassfields peoples to stem the German tide.[23] Once the protectorate was officially declared, the German military was purposely slow to enlist locals as soldiers lest they acquire too great a proficiency with guns and turn those guns on the whites. This fear persisted because the Germans never numbered more than 200 white officers and barely enlisted 1,300 Africans as troops.[24] The army in the protectorate remained small because its major task was to suppress scattered African rebellions, not to ward off other Europeans. German planners anticipated that the fate of their African empire would be settled, if necessary, by wars in Europe, not in Africa itself. Never really deployed at forts, the troops were first grouped into three expeditionary companies, who were marched from place to place to suppress revolts. These troops were all that stood between the meagre German administration and the African population.[25] The Germans used these troops to combat many revolts against their rule. Germans met armed resistance from the Bassa-Bakoko, one of the largest ethnic groups of the coastal and northwest Kamerun areas, who staged an armed rebellion trying to halt German inland penetration, but were defeated between 1892 and 1895.[26] As the Germans subdued rebellious Africans, their expeditions also resulted in obtaining forced laborers for the coastal plantations. This activity led to the depopulation of inland zones. The exploitative nature of the German regime swept the natives of Kamerun into a changed world. Suddenly, the barter economy was replaced by a money economy.[27]

German Togoland

German control of Togoland dates back to February 1884 when a group of German soldiers kidnapped chiefs in Anecho, in present-day south-Eastern Togo and forced them into negotiations among the German warship Sophie.[28] To establish official control of the rest of the region, Germany signed treaties with Great Britain. During its thirty-year occupation by the Germans, Togoland was held up by many European imperialists as a model colony, primarily because the German regime produced balanced budgets and was devoid of any major wars. The formation of impressive rail networks and telegraph systems further supported this opinion. However, it was a combination of forced labor and excessive taxation imposed on the Togolanders that created these. While Togoland might have appeared to be "model" to Europeans, Togolanders endured a regime characterized by the aforementioned labor and taxation policies, harsh punishments inflicted by German district officers, grossly inadequate health care and education systems, and prohibition from many commercial activities.[29] The Germans made sure that they had complete control over both Togoland and its inhabitants. However, at the start of the First World War, the combined forces of the British and the French invaded the colony and the Germans capitulated, after only a few skirmishes, on 26 August 1914.[30] The Togolanders were beyond thankful to be freed from German rule, this conflicted with the previously-held contention among many European imperialists that Togoland was a model colony.[31] A British writer, Albert E Calvert, tried to understand this distinct difference; Calvert argued that the natives of Togoland ended their ‘allegiance’ with the Germans as soon as the Germans were put in a position of pressure, that the terrible treatment they endured under the Germans was the reason for their welcoming of the British and French invasion as well as the joy they exerted after the German surrender.[32] Germans quickly responded, to defend their honor, by stating that the Africans were more than satisfied with German sovereignty, that they desired nothing more than its continuance.[33] Some Germans also argued that the colonial territories which blossomed under their rule were economically ruined after they were expunged.[34] This tension between the Allied and German governments over German colonies lasted until the outbreak of World War II.

German South West Africa and the Herero and Nama Genocide

The Germans colonized South West Africa in a different manner than the rest of their holdings. The main goal of the Germans in Namibia was to provide a Lebensraum for its people; more territory that a state believes is needed for its natural development. German urban areas were overcrowded because of a recent population boom, the poor became people without space to operate in. German officials understood that their people needed space to grow and prosper; the Germans faced a choice of decline through lack of space and loss of population (as many had already left for America), or expanding into new lands.[35] The Germans realized that Namibia would be perfect for this, and ethnic cleansing was necessary to create the Lebensraum. Before it reached that point, the Germans started off slow in Namibia, from a position of relative weakness. Originally, the Germans used negotiation and bargaining tactics with the Herero for land. These practices were completely at odds with the German and overall European belief that they were superior to Africans and the Germans resented it.[36] The Germans expected to come in and simply begin colonization efforts, but instead they were renting land from the people who they were supposed to be colonizing; a paradoxical relationship. Eventually, when the Germans believed the time was right to assert more control, they began disputing the Herero claims over land. The Germans also started to treat the Herero harshly, started minor instances of conflict with them, and raped their women; the Herero became convinced that resistance was the only way to combat this.[37] As the Germans became more determined to take Herero land for Lebensraum, the Herero edged closer to open rebellion and killed a number of Germans as a result of this treatment. After the first Germans were killed by the Herero, the Germans turned extreme and believed ethnic cleansing was necessary. Not all Herero acted against the Germans originally and even expressed their continued loyalty. In fact, it was more of a localized rebellion, but the Germans did not care; they attempted to wipeout as many Herero as possible. The Germans forced many Herero into a war they did not want. It was a mixture of nationalism, militarism, and racism that prompted Kaiser Wilhelm II to send a large army to crush the Herero.[38] Negotiation was not an option and the Herero did not see any of this coming; they believed the earlier disputes had been resolved; the Herero moved as far away as possible from the German settlements to try and survive. The Herero hoped for negotiations, but a colonial army arrived instead. The Germans attacked the Herero where they were mainly gathered, right next to the Kalahari Desert. The Germans encircled the Herero but left one part open for them to escape into the Kalahari, expecting them to die of starvation and thirst.[39] After the Germans pushed the Herero deeper and deeper into the Kalahari, they created a wall of guard posts to seal them off. The Germans believed this behavior was entirely acceptable, there was an official sanctioning of genocide. Eventually, with pressures from inside the German government as more people learned about the brutality, the Kaiser was forced to tell his military to accept the surrender of the Herero. To persuade their surrender, the Germans told the Herero they would be allowed to return to their homeland; that they had been pardoned by the Kaiser.[40] However, this was a lie and the Herero that were rounded up were sent to concentration camps. The Herero were beaten, overworked, and starved to death by the army of the Second Reich, this became the first genocide of the twentieth century. There were almost no free Herero people after the establishment of the concentration camps; slave labor became part of the colonial economy. The German colony rented slaves to private companies, but some companies were so big that they ran their own concentration camps. Arguably the most brutal camps in Namibia was the one located on Shark Island. Entrance to this camp was strictly forbidden as it was an extermination camp, unlike the forced labor camps. Most victims of the Shark Island camp were the Nama people; they saw the tragedy that the Herero went through and rebelled against the Germans because of that.[41] Overall, the camps in Namibia provided the blueprint for death camps of 20th century, that Nazi Germany used. The African natives were shipped by cattle cars and taken to a place far from public view to be exterminated. The idea of separating people out from typical society and killing them as quick as possibly was probably born on Shark Island.

Impact of Treaty of Versailles

Before the Treaty of Versailles was even signed, Great Britain, France, and Japan had total control over the German colonies since 1915, except for East Africa.[42] Great Britain and France had made secret arrangements splitting German territory and the Treaty of Versailles only cemented what had already taken place. The treaty only further confirmed that “Germany renounced to the Allied and Associated powers all rights and titles to her overseas territories”.[43] After World War I, Germany did not just lose territory but lost commercial footholds, spheres of influence, and imperialistic ambitions of continued expansion. Germany was severely weakened by the Treaty of Versailles but attempted everything to regain their overseas empire. The Germans thought the dispossession of their colonies was an injustice, and reiterated their economic need of the colonies, and their duty to civilize the backward races.[44] The Germans put forward two proposals for colonial settlement: first, that a special committee, who would at least hear Germany’s side of the issue, handle the matter; and second, that Germany be allowed to administer her former colonies.[45] The Allies rejected these proposals and refused to alter the colonial settlement that an agreement was reached upon. The Allies rejected the proposals because the native inhabitants of the German colonies were strongly opposed to being brought under their control again. German frustration from their territories being stolen from them and the extensive amount of reparations they were forced to pay led directly to World War II.

List of colonies

- Established by Brandenburg-Prussia, 1682–1721:

- Established by the German Empire, 1884–1919:

See also

References

- Iliffe, John. A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge University Press, 1979, 88.

- Iliffe, John. A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge University Press, 1979, 90.

- Iliffe, John. A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge University Press, 1979, 92.

- Iliffe, John. A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge University Press, 1979, 92-93.

- Iliffe, John. A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge University Press, 1979, 116.

- Iliffe, John. A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge University Press, 1979, 118.

- Iliffe, John. A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge University Press, 1979, 118.

- Iliffe, John. A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge University Press, 1979, 118.

- Iliffe, John. A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge University Press, 1979, 119.

- Iliffe, John. A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge University Press, 1979, 119.

- Iliffe, John. A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge University Press, 1979, 119.

- Iliffe, John. A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge University Press, 1979, 120.

- Iliffe, John. A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge University Press, 1979, 120.

- Iliffe, John. A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge University Press, 1979, 120.

- Reid, Richard J. A History of Modern Africa: 1800 to the Present. John Wiley & Sons Limited, 2020, 183.

- Reid, Richard J. A History of Modern Africa: 1800 to the Present. John Wiley & Sons Limited, 2020, 183.

- Reid, Richard J. A History of Modern Africa: 1800 to the Present. John Wiley & Sons Limited, 2020, 194.

- Reid, Richard J. A History of Modern Africa: 1800 to the Present. John Wiley & Sons Limited, 2020, 194.

- Richardson, Marjorie L. From German Kamerun to British Cameroons, 1884--1961 with Special Reference to the Plantations, University of California, Los Angeles, Ann Arbor, 1999. ProQuest, https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.albany.edu/docview/304496352?accountid=14166 (25).

- Richardson, Marjorie L. From German Kamerun to British Cameroons, 1884--1961 with Special Reference to the Plantations, University of California, Los Angeles, Ann Arbor, 1999. ProQuest, https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.albany.edu/docview/304496352?accountid=14166 (25).

- ABRAMSON, PAMELA J. The Development Of German Colonial Administrative Practices In Kamerun, Duquesne University, Ann Arbor, 1976. ProQuest, https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.albany.edu/docview/302789694?accountid=14166 (1).

- Richardson, Marjorie L. From German Kamerun to British Cameroons, 1884--1961 with Special Reference to the Plantations, University of California, Los Angeles, Ann Arbor, 1999. ProQuest, https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.albany.edu/docview/304496352?accountid=14166 (25).

- Richardson, Marjorie L. From German Kamerun to British Cameroons, 1884--1961 with Special Reference to the Plantations, University of California, Los Angeles, Ann Arbor, 1999. ProQuest, https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.albany.edu/docview/304496352?accountid=14166 (29)

- Richardson, Marjorie L. From German Kamerun to British Cameroons, 1884--1961 with Special Reference to the Plantations, University of California, Los Angeles, Ann Arbor, 1999. ProQuest, https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.albany.edu/docview/304496352?accountid=14166 (30)

- Richardson, Marjorie L. From German Kamerun to British Cameroons, 1884--1961 with Special Reference to the Plantations, University of California, Los Angeles, Ann Arbor, 1999. ProQuest, https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.albany.edu/docview/304496352?accountid=14166 (30)

- Richardson, Marjorie L. From German Kamerun to British Cameroons, 1884--1961, with Special Reference to the Plantations, University of California, Los Angeles, Ann Arbor, 1999. ProQuest, https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.albany.edu/docview/304496352?accountid=14166 (33).

- ABRAMSON, PAMELA J. The Development Of German Colonial Administrative Practices In Kamerun, Duquesne University, Ann Arbor, 1976. . ProQuest, https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.albany.edu/docview/302789694?accountid=14166 (2).

- Laumann, Dennis. “A Historiography of German Togoland, or the Rise and Fall of a ‘Model Colony.’” History in Africa, vol. 30, 2003, pp. 195–211. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3172089 (195-6).

- Laumann, Dennis. “A Historiography of German Togoland, or the Rise and Fall of a ‘Model Colony.’” History in Africa, vol. 30, 2003, pp. 195–211. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3172089 (196).

- Laumann, Dennis. “A Historiography of German Togoland, or the Rise and Fall of a ‘Model Colony.’” History in Africa, vol. 30, 2003, pp. 195–211. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3172089 (196).

- Laumann, Dennis. “A Historiography of German Togoland, or the Rise and Fall of a ‘Model Colony.’” History in Africa, vol. 30, 2003, pp. 195–211. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3172089 (197).

- Laumann, Dennis. “A Historiography of German Togoland, or the Rise and Fall of a ‘Model Colony.’” History in Africa, vol. 30, 2003, pp. 195–211. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3172089 (199-200).

- Laumann, Dennis. “A Historiography of German Togoland, or the Rise and Fall of a ‘Model Colony.’” History in Africa, vol. 30, 2003, pp. 195–211. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3172089 (201).

- Laumann, Dennis. “A Historiography of German Togoland, or the Rise and Fall of a ‘Model Colony.’” History in Africa, vol. 30, 2003, pp. 195–211. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3172089 (201).

- Bildungskanal. “Namibia: Genocide and the Second Reich (BBC).” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rbon6HqzjEI

- Bildungskanal. “Namibia: Genocide and the Second Reich (BBC).” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rbon6HqzjEI

- Bildungskanal. “Namibia: Genocide and the Second Reich (BBC).” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rbon6HqzjEI

- Bildungskanal. “Namibia: Genocide and the Second Reich (BBC).” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rbon6HqzjEI

- Bildungskanal. “Namibia: Genocide and the Second Reich (BBC).” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rbon6HqzjEI

- Bildungskanal. “Namibia: Genocide and the Second Reich (BBC).” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rbon6HqzjEI

- Bildungskanal. “Namibia: Genocide and the Second Reich (BBC).” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rbon6HqzjEI

- Townsend, Mary Evelyn. The Rise and Fall of Germany's Colonial Empire: 1884-1918. Howard Fertig, 1966, 377.

- Townsend, Mary Evelyn. The Rise and Fall of Germany's Colonial Empire: 1884-1918. Howard Fertig, 1966, 379.

- Townsend, Mary Evelyn. The Rise and Fall of Germany's Colonial Empire: 1884-1918. Howard Fertig, 1966, 387-88.

- Townsend, Mary Evelyn. The Rise and Fall of Germany's Colonial Empire: 1884-1918. Howard Fertig, 1966, 388.