Godzilla vs. Destoroyah

Godzilla vs. Destoroyah (ゴジラvsデストロイア, Gojira tai Destoroyah, also known as Godzilla vs. Destroyer)[3] is a 1995 Japanese kaiju film directed by Takao Okawara, written by Kazuki Ōmori, and produced by Shōgo Tomiyama. Produced and distributed by Toho Studios, it is the 22nd installment in the Godzilla franchise, and is the seventh and final film in the franchise's Heisei period. The film features the fictional monster characters Godzilla, Godzilla Junior, and Destoroyah, and stars Takuro Tatsumi, Yōko Ishino, Yasufumi Hayashi, Sayaka Osawa, Megumi Odaka, Masahiro Takashima, Momoko Kochi, and Akira Nakao, alongside Kenpachiro Satsuma as Godzilla, Hurricane Ryu as Godzilla Junior, and both Ryo Hariya and Eiichi Yanagida as Destoroyah.

| Godzilla vs. Destoroyah | |

|---|---|

_Japanese_theatrical_poster.jpg.webp) Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Takao Okawara |

| Produced by | Shōgo Tomiyama |

| Written by | Kazuki Ōmori |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Akira Ifukube |

| Cinematography | Yoshinori Sekiguchi |

| Edited by | Chizuko Osada |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Toho |

Release date |

|

Running time | 102 minutes |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

| Box office | ¥3.5 billion[1] ($42 million)[2] |

In the film, Godzilla's heart, which acts as a nuclear reactor, is nearing a nuclear meltdown which threatens the Earth. Meanwhile, a colony of mutated creatures known as Destoroyah emerge from the ocean, changing form and terrorizing Japan, forcing the Japanese Self-Defense Forces to devise a plan to eliminate both threats.

Godzilla vs. Destoroyah received global publicity following an announcement by Toho that the film would feature the death of Godzilla. It was the final film to be scored by composer Akira Ifukube before his death in 2006. The film was released theatrically in Japan on December 9, 1995, and received a direct-to-video release in the United States in 1999 by Columbia TriStar Home Video. It was the last Godzilla film to be produced by any studio until the 1998 film Godzilla, and was the last Godzilla film to be produced by Toho until the 1999 film Godzilla 2000.

Plot

In 1996, following the death of SpaceGodzilla, Miki Saegusa of the United Nations Godzilla Countermeasures Center (UNGCC) travels to Birth Island to check on Godzilla and Little Godzilla, only to find the entire island destroyed and both monsters missing. Not long afterwards, Godzilla reappears in Hong Kong, his body covered in glowing lava-like rashes. The JSDF hires college student Kenkichi Yamane, the grandson of Dr. Kyohei Yamane, to work at the center in an attempt to unravel the mystery of Godzilla's condition. Yamane suspects that Godzilla's heart, which acts as a nuclear reactor, is undergoing a nuclear meltdown as a result of Godzilla absorbing the energy released from a uranium deposit on Birth Island that had been triggered by a volcanic eruption. Yamane theorizes that when Godzilla's temperature reaches 1,200 °C, he will explode with a force approximately "1,000 times greater than all nuclear weapons put together, a burst of power unseen since time began," which will be hot enough to ignite Earth's atmosphere and reduce the planet's surface to ash.

The JSDF deploys a flying combat vehicle outfitted with anti-nuclear cold weapons, the Super X III, in an effort to reverse Godzilla's self-destruction; while Godzilla’s meltdown is not stopped, it is halted long enough to temporarily render him unconscious. Meanwhile, scientists discover that Dr. Serizawa's Oxygen Destroyer, which was used against the original Godzilla in 1954, has awoken and mutated a colony of Precambrian organisms lying dormant in Tokyo Bay. The creatures combine into several man-sized crab-like creatures and begin wreaking havoc after killing all the fish in an aquarium. After several deadly skirmishes with the JSDF, the creatures, dubbed "Destoroyah", merge into a single Aggregate form, which then transforms again into its Flying form and leaves the scene.

Meanwhile, Godzilla awakens from his encounter with the Super X III only instead of exploding; Godzilla's condition has worsened to the point that he will suffer a bodily meltdown which could potentially destroy the planet through a China syndrome-like incident. Miki locates Little Godzilla - now named Godzilla Junior - who has grown significantly as a result of the destruction of Birth Island and resembles the larger Godzilla very closely. Miki is instructed to telepathically lure Godzilla Junior to Tokyo, hoping that Godzilla will follow and be killed by Destoroyah. Junior arrives and battles Destoroyah's Aggregate, which severely injures Junior by sending micro oxygen into the wound, and Flying form, who is seemingly defeated after being blown into an electrical plant. Godzilla arrives at Haneda Airport and reunites with Godzilla Junior, only for the electrical plant Destoroyah was defeated at to suddenly explode, revealing Destoroyah’s final, Perfect form, which was created after the aggregate absorbed Junior's DNA during the previous fight. Before Godzilla can fight Destoroyah, Destoroyah kills Junior by dropping him from a great height onto Ariake Coliseum and blasting him with his Micro-Oxygen beam leaving Miki and Godzilla devastated over Junior's death. After being dragged away from the location of Junior by Destoroyah, Godzilla manages to subdue his adversary for just long enough to reach the airport for a second time. Godzilla mournfully approaches the body of Junior.

Godzilla tries to revive Godzilla Junior. Godzilla's radiation briefly succeeds in bringing Junior back to life, but only for a few seconds, and Junior dies again, this time at Godzilla's feet. Enraged and bereaved, Godzilla's meltdown begins to accelerate, but Destoroyah returns, brutally attacking Godzilla. In the ensuing battle, which rages across the airport and neighbouring areas of Tokyo, Godzilla's meltdown gives him an extremely powerful version of the Spiral Heat Ray, the Infinite Heat Ray. Destoroyah is severely wounded by Godzilla after he fires the beam through his shoulder and head frill. Realizing the odds are against him, Destoroyah tries to retreat, but the JSDF shreds Destoroyah's wings after firing on him with a set of freezer tanks. Destoroyah plummets to the superheated ground, and is killed instantly, dissipating into a white mist.

Godzilla, having avenged Godzilla Junior, slowly begins to die from the meltdown, but the JSDF is able to minimize the damage with the freeze weapons. While successful in preventing Earth's destruction, the JSDF is unable to prevent the massive nuclear fallout from rendering Tokyo uninhabitable while Miki tearfully says goodbye to Godzilla. Suddenly, the radiation levels plummet and a familiar roar is heard. Godzilla Junior, having absorbed the energy from the senior Godzilla's death, has not only revived but grown into the new Godzilla.

Cast

- Takuro Tatsumi as Dr. Kensaku Ijuin (伊集院 研作, Ijuin Kensaku)

- Yōko Ishino as Yukari Yamane (山根 ゆかり, Yamane Yukari)

- Yasufumi Hayashi as Kenkichi Yamane (山根 健吉, Yamane Kenkichi)

- Megumi Odaka as Miki Saegusa (三枝 未希, Seagusa Miki)

- Sayaka Osawa as Meru Ozawa (小沢 芽留, Ozawa Meru)

- Saburo Shinoda as Professor Fukazawa (深沢 博士, Fukazawa-hakase)

- Akira Nakao as Cmdr. Takaaki Aso (麻生 孝昭, Aso Takaaki)

- Momoko Kōchi as Emiko Yamane (山根 恵美子, Yamane Emiko)

- Masahiro Takashima as Major Sho Kuroki

- Takehiro Murata as Soichiro Hayami, Yukari's Editor

- Shigeru Kamiyama as Goto (後藤, Gotō)

- Kenpachiro Satsuma as Godzilla

- Ryo Hariya and Eiichi Yanagida as Destoroyah

- Hurricane Ryu as Godzilla Junior

Production

After Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla II and Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla failed to match the attendance figures of the highly successful Godzilla vs. Mothra, producer Shogo Tomiyama announced in the summer of 1995 that the next Godzilla movie would be the series' final installment. Screenwriter Kazuki Ōmori initially proposed a story treatment entitled Godzilla vs. Ghost Godzilla, in which the current Heisei Godzilla would have faced off against the ghost of the original 1954 Godzilla. While this idea was scrapped, it was decided to maintain the reference to the original film by reintroducing the Oxygen Destroyer, the weapon that killed the original Godzilla 40 years earlier. In the original script, the final battle was to have taken place in the then still under construction World City, a development project costing $2.35 billion, though Tokyo governor Yukio Aoshima scrapped the project on account of its unpopularity with taxpayers. Toho began promoting the movie via large placards featuring the kanji text ゴジラ死す ("Godzilla dies").[5][6]

Five days prior to the film's release, a large bronze sculpture of Godzilla was erected on the Hibiya cinema district. After the film's release, Toho studios was bombarded by letters of protest demanding Godzilla's resurrection, and several mourners gathered at the bronze statue to leave ¥10-100 coins and tobacco. One Japanese travel agency commemorated Godzilla's demise by hosting tours of various locations destroyed by Godzilla throughout its 40-year tenure. Toho representatives assured the public that Godzilla's death was not permanent and that they were considering rebooting the series in 2005, after the American Godzilla had its run.[6] Ultimately, Toho returned to the series in 1999 - six years earlier than originally stated - with the first film of the "Millennium Era", Godzilla 2000: Millennium.

Special effects

Effects artist Koichi Kawakita originally envisioned Godzilla being luminescent, and coated a Godzilla suit with luminescent paint and reflective tape, though this was deemed to look too unnatural. The final product was the result of placing 200 small orange light bulbs on the suit previously used for Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla and covering them with semitransparent vinyl plates. The resulting suit proved difficult for suit actor Kenpachiro Satsuma to perform in, as the cable powering the light bulbs added extra weight to the suit, and the carbonic acid gas emitted by the costume nearly suffocated him six times.[7] For Godzilla's confrontation with the Super-X III, the now-expendable suit previously used for Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla II was used, as it was predicted that it would have suffered irreparable damage from the liquid nitrogen used during the scene.[8]

Godzilla Junior and Destoroyah were also portrayed via traditional suitmation techniques, though because the Junior suit was almost the same size as the main Godzilla one, a small animatronic prop was used in scenes where Junior interacts with its father. During the scene where the JSDF bombards the immature Destoroyahs, the creatures were realized with Bandai action figures. Kawakita made greater use of CGI than in previous installments, having used it for the Super-X III's freezing of Godzilla, shots showing helicopters, computer schematics showing the outcome of Godzilla's meltdown, and Godzilla's death.[9][10]

Music

Composer Akira Ifukube, who had previously refused to compose the score of Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla, agreed to work on Godzilla vs. Destoroyah's soundtrack since he "felt that since [he had] been involved in Godzilla's birth, it was fitting for [him] to be involved in his death." For Destoroyah's theme, Ifukube had initially wanted to give each of Destoroyah's forms their own motif, though he subsequently chose to give them all the same theme. He chose not to use the Oxygen Destroyer theme from the original 1954 film, as he felt that the theme expressed the tragedy of the weapon's creator, and thus was inappropriate for a monster. He also deliberately avoided using Godzilla's death theme from the original film, as he wanted to focus more on the dark side of humanity rather than on Godzilla itself.[11] In describing his composition of Godzilla's death theme, he stated that it was one of the most difficult pieces he had ever composed, and that he approached it as if he were writing the theme to his own death.[12]

English version

After the film was released in Japan, Toho commissioned a Hong Kong company to dub the film into English. In this international version of the movie, an English title card was superimposed over the Japanese title, as had been done with the previous 1990s Godzilla films.

Columbia TriStar Home Entertainment released Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla and Godzilla vs. Destoroyah on home video on January 19, 1999, the first time that either film had been officially released in the United States. TriStar used the Toho dubs, but cut the end credits and created new titles and opening credits for both films. The complete Toho international version of Godzilla vs. Destoroyah has been broadcast on several premium movie channels since the early 2000s.

Reception

Box office

The film sold approximately 4 million tickets in Japan, and grossed a total of ¥3.5 billion [1] ($42 million ).[2] It earned ¥2 billion in distribution income (around $18 million ).[13] It was the number one domestic film at the box office in Japan by distribution income for 1996 and Fourth Place overall behind Twister, SE7EN and Mission: Impossible.[14]

Critical reception

Critical and fan reaction to the film has been very positive. Toho Kingdom said, "With an elegant style, a powerful plot, brilliant effects, and believable acting, this entry is definitely a notch above favorites from all three timelines, and its impact on the series is challenged by only a handful of competitors. Godzilla vs. Destoroyah is without a doubt a paradigm all its own."[15] Michael Hubert of Monster Zero praised the "spectacular monster battles," calling Godzilla vs. Destoroyah "a great movie" and "one to add to your collection," adding: "Even for non-Godzilla fans, this movie might help dispel some of the preconceptions you have about Godzilla's 'cheese factor'."[16]

Japan Hero called the film "a work of art" and "a must see for anyone who loves Godzilla" that features "something for everyone".[17] Mike Bogue of American Kaiju felt the film suffered from "several visual weaknesses" and a "disappointing editing", but that "the positive aspects of the visuals outweigh the negatives" and praised the film for "treating Godzilla with the same awe, majesty, and terror as [the original 1954 Godzilla]." [18]

Stomp Kaiju gave the film a score of 4 out of 5, saying "This is one of the biggest productions the big G ever had. The new Super-X III, looking black and stealth-bombery, is a great addition, and the return of Lt. Sho Kuroki (Masashiro Takashima) from Godzilla vs Biollante as its pilot is a nice touch." as well as saying that "There are several small ways in which this film pays homage to the Godzilla legacy, like a cameo appearance by Emiko (Momoko Kouchi) from Godzilla (1954), and they really make the movie. It's nice to see a company handle its property, beloved by millions, with a little respect and knowledge of that property's history".[19] Tim Brayton of Alternate Ending called it "A Godzilla movie of particular grandeur and seriousness", saying "it's the best Godzilla film of the VS era: visually robust, focused on great heaving gestures and emotions that work so much better in this franchise than the attempts at human-scaled storytelling that some of the more recent sequels gestured towards. It flags its seriousness and desire to have an impact maybe a bit too eagerly, but the results are hard to argue with: it is a sufficiently epic finale for an iconic character, and our foreknowledge of how far awry things would go with the plan to bring a temporary close to the Japanese Godzilla saga shouldn't color just how bold and roiling that close succeeded in being, in its moment".[20] One of the few mixed reviews came from DVD Talk, saying that "Although it benefits from having an honest-to-goodness storyline with some continuity from the previous Godzillas (going back to the earliest films), Destoroyah's portentous pacing, cardboard-thin characters and cheeseball effects apparently served as a primer on what not to do when Hollywood picked up the franchise". [21]

Awards

| Year | Award | Category | Recipient | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | Golden Awards | Best Grossing Film Award | Godzilla vs. Destoroyah | Won |

| Japan Academy Awards | Best Special Effects | Godzilla vs. Destoroyah | Won | |

| Best Editing | Chizuko Osada | Nominated | ||

| Best Sound | Kazuo Miyauchi | Nominated |

Home media

The film has been released on DVD by Columbia/Tristar Home Entertainment on February 1, 2000 along with Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla.[22]

It was released on blu-ray in The Toho Godzilla Collection by Sony on May 6, 2014 along with Godzilla vs. Megaguirus.[23]

References

- Ryfle 1998, p. 346.

- "Yen to USD".

- Ryfle 1998, p. 305.

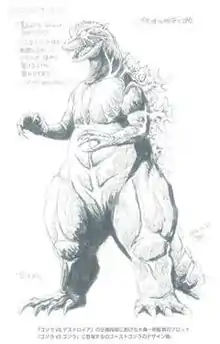

- Nishikawa, Shinji (2016), 西川伸司ゴジラ画集 [Drawing Book of Godzilla], Yosensha, ISBN 480030959X

- Ryfle 1998, p. 306.

- Ryfle 1998, p. 313.

- Ryfle 1998, p. 310.

- "Godzilla vs. Destoroyah 20 Years Later-Part I: Making Monsters Meltdown", Scified (January 11, 2016)

- Ryfle 1998, p. 308.

- Ryfle 1998, p. 309.

- David Milner, "Akira Ifukube Interview III", Kaiju Conversations (December 1995)

- Ryfle 1998, p. 316.

- "Godzilla vs. Destoroyah". Tohokingdom.com. Retrieved 2014-07-20.

- "Kako haikyū shūnyū jōi sakuhin 1996-nen" (in Japanese). Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- "Godzilla vs. Destoroyah (Review)". Tohokingdom.com. 2005-04-16. Retrieved 2014-07-20.

- Archived June 24, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Archived September 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "American Kaiju: Mike Bogue's Articles and Reviews: Godzilla vs. Destoroyah". Americankaiju.kaijuphile.com. 1995-12-09. Retrieved 2014-07-20.

- "Godzilla vs. Destoroyah: review by Scott Hamilton and Chris Holland". Stomp Tokyo. 1999-11-11. Retrieved 2017-03-14.

- "REVIEW ALL MONSTERS! – SOME SAY THE WORLD WILL END IN FIRE". Alternate Ending. 2014-03-24. Retrieved 2017-03-14.

- "Godzilla Vs. Destoroyah/Godzilla Vs. Megaguirus Set (Blu-ray) Review". DVD Talk. 2014-05-06. Retrieved 2017-03-14.

- "Rewind @ www.dvdcompare.net - Godzilla vs. Destoroyah AKA Gojira VS Desutoroia (1995)". Dvdcompare.net. Retrieved 2014-07-20.

- "Godzilla vs. Destoroyah Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved 2014-07-20.

- Bibliography

- Ryfle, Steve (1998). Japan’s Favorite Mon-Star: The Unauthorized Biography of the Big G. ECW Press. ISBN 1550223488.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Godzilla vs. Destoroyah |

- Godzilla vs. Destoroyah at IMDb

- Godzilla vs. Destoroyah at AllMovie

- Godzilla vs. Destoroyah at Rotten Tomatoes

- "ゴジラvsデストロイア (Gojira tai Desutoroia)" (in Japanese). Japanese Movie Database. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- Godzilla vs. Destoroyah on Wikizilla