Gravitation of the Moon

The acceleration due to gravity on the surface of the Moon is about 1.625 m/s2, about 16.6% that on Earth's surface or 0.166 ɡ.[1] Over the entire surface, the variation in gravitational acceleration is about 0.0253 m/s2 (1.6% of the acceleration due to gravity). Because weight is directly dependent upon gravitational acceleration, things on the Moon will weigh only 16.6% (≈ 1/6) of what they weigh on the Earth.

Gravitational field

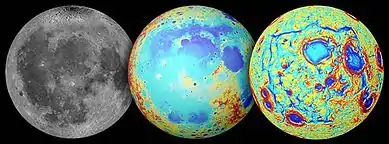

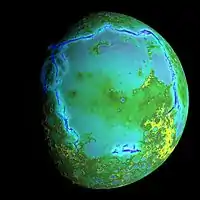

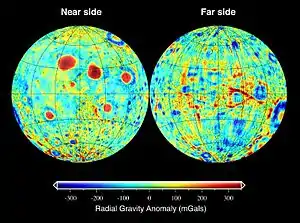

The gravitational field of the Moon has been measured by tracking the radio signals emitted by orbiting spacecraft. The principle used depends on the Doppler effect, whereby the line-of-sight spacecraft acceleration can be measured by small shifts in frequency of the radio signal, and the measurement of the distance from the spacecraft to a station on Earth. Since the gravitational field of the Moon affects the orbit of a spacecraft, one can use these tracking data to detect gravity anomalies. However, because of the Moon's synchronous rotation it is not possible to track spacecraft from Earth much beyond the limbs of the Moon, so until the recent Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) mission the far-side gravity field was not accurately known.

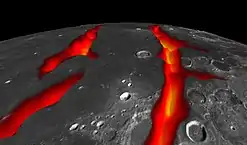

A major feature of the Moon's gravitational field is the presence of mascons, which are large positive gravity anomalies associated with some of the giant impact basins. These anomalies significantly influence the orbit of spacecraft around the Moon, and an accurate gravitational model is necessary in the planning of both manned and unmanned missions. They were initially discovered by the analysis of Lunar Orbiter tracking data:[2] navigation tests prior to the Apollo program showed positioning errors much larger than mission specifications.

Mascons are in part due to the presence of dense mare basaltic lava flows that fill some of the impact basins.[3] However, lava flows by themselves cannot fully explain the gravitational variations, and uplift of the crust-mantle interface is required as well. Based on Lunar Prospector gravitational models, it has been suggested that some mascons exist that do not show evidence for mare basaltic volcanism.[4] The huge expanse of mare basaltic volcanism associated with Oceanus Procellarum does not cause a positive gravity anomaly. The center of gravity of the Moon does not coincide exactly with its geometric center, but is displaced toward the Earth by about 2 kilometers.[5]

References

- C. Hirt; W. E. Featherstone (2012). "A 1.5 km-resolution gravity field model of the Moon". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 329–330: 22–30. Bibcode:2012E&PSL.329...22H. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2012.02.012. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

- P. Muller; W. Sjogren (1968). "Mascons: Lunar mass concentrations". Science. 161 (3842): 680–84. Bibcode:1968Sci...161..680M. doi:10.1126/science.161.3842.680. PMID 17801458. S2CID 40110502.

- Richard A. Kerr (12 April 2013). "The Mystery of Our Moon's Gravitational Bumps Solved?". Science. 340 (6129): 138–39. doi:10.1126/science.340.6129.138-a. PMID 23580504.

- A. Konopliv; S. Asmar; E. Carranza; W. Sjogren; D. Yuan (2001). "Recent gravity models as a result of the Lunar Prospector mission". Icarus. 50 (1): 1–18. Bibcode:2001Icar..150....1K. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.18.1930. doi:10.1006/icar.2000.6573.

- Nine Planets