Week

A week is a time unit equal to seven days. It is the standard time period used for cycles of rest days in most parts of the world, mostly alongside—although not strictly part of—the Gregorian calendar.

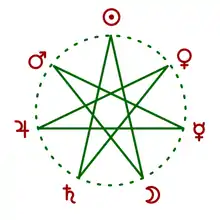

In many languages, the days of the week are named after classical planets or gods of a pantheon. In English, the names are Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday and Sunday, then returning to Monday. Such a week may be called a planetary week. This arrangement is similar to a week in the New Testament in which the seven days are simply numbered with the first day being a Christian day of worship (aligned with Sunday, offset from ISO 8601 by one day) and the seventh day being a sabbath day (Saturday).

While, for example, the United States, Canada, Brazil, Japan and other countries consider Sunday as the first day of the week, and while the week begins with Saturday in much of the Middle East, the international ISO 8601 standard[lower-alpha 1] and most of Europe has Monday as the first day of the week. The ISO standard includes the ISO week date system, a numbering system for weeks within a given year, where each week starting on a Monday is associated with the year that contains that week's Thursday (so that if a year starts in a long weekend Friday–Sunday, week number one of the year will start after that, and if, conversely, a year ends on a Monday, Tuesday or Wednesday, the last days of the year are counted as part of week 1 of the following year). ISO 8601 assigns numbers to the days of the week, running from 1 for Monday through 7 for Sunday.

The term "week" is sometimes expanded to refer to other time units comprising a few days, such as the nundinal cycle of the ancient Roman calendar, the "work week", or "school week" referring only to the days spent on those activities.

Name

The English word week comes from the Old English wice, ultimately from a Common Germanic *wikōn-, from a root *wik- "turn, move, change". The Germanic word probably had a wider meaning prior to the adoption of the Roman calendar, perhaps "succession series", as suggested by Gothic wikō translating taxis "order" in Luke 1:8.

The seven-day week is named in many languages by a word derived from "seven". The archaism sennight ("seven-night") preserves the old Germanic practice of reckoning time by nights, as in the more common fortnight ("fourteen-night").[1] Hebdomad and hebdomadal week both derive from the Greek hebdomás (ἑβδομάς, "a seven"). Septimana is cognate with the Romance terms derived from Latin septimana ("a seven").

Slavic has a formation *tъ(žь)dьnь (Serbian тједан, tjedan, Croatian tjedan, Ukrainian тиждень, tyzhden, Czech týden, Polish tydzień), from *tъ "this" + *dьnь "day". Chinese has 星期, as it were "planetary time unit".

Definition and duration

A week is defined as an interval of exactly seven days,[lower-alpha 2] so that technically, except at daylight saving time transitions or leap seconds,

- 1 week = 7 days = 168 hours = 10,080 minutes = 604,800 seconds.

With respect to the Gregorian calendar:

- 1 Gregorian calendar year = 52 weeks + 1 day (2 days in a leap year)

- 1 week = 1600⁄6957 ≈ 22.9984% of an average Gregorian month

In a Gregorian mean year, there are 365.2425 days, and thus exactly 52 71⁄400 or 52.1775 weeks (unlike the Julian year of 365.25 days or 52 5⁄28 ≈ 52.1786 weeks, which cannot be represented by a finite decimal expansion). There are exactly 20,871 weeks in 400 Gregorian years, so 5 February 1621 was a Friday just as was 5 February 2021.

Relative to the path of the Moon, a week is 23.659% of an average lunation or 94.637% of an average quarter lunation.

Historically, the system of dominical letters (letters A to G identifying the weekday of the first day of a given year) has been used to facilitate calculation of the day of week. The day of the week can be easily calculated given a date's Julian day number (JD, i.e. the integer value at noon UT): Adding one to the remainder after dividing the Julian day number by seven (JD modulo 7 + 1) yields that date's ISO 8601 day of the week. For example, the Julian day number of 5 February 2021 is 2459251. Calculating 2459251 mod 7 + 1 yields 5, corresponding to Friday.[2]

Days of the week

The days of the week were originally named for the classical planets. This naming system persisted alongside an "ecclesiastical" tradition of numbering the days, in ecclesiastical Latin beginning with Dominica (the Lord's Day) as the first day. The Greco-Roman gods associated with the classical planets were rendered in their interpretatio germanica at some point during the late Roman Empire, yielding the Germanic tradition of names based on indigenous deities.

The ordering of the weekday names is not the classical order of the planets (by distance in the planetary spheres model, nor, equivalently, by their apparent speed of movement in the night sky). Instead, the planetary hours systems resulted in succeeding days being named for planets that are three places apart in their traditional listing. This characteristic was apparently discussed in Plutarch in a treatise written in c. AD 100, which is reported to have addressed the question of Why are the days named after the planets reckoned in a different order from the actual order? (the text of Plutarch's treatise has been lost).[3]

| Sunday | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | |

| Planet | Sun | Moon | Mars | Mercury | Jupiter | Venus | Saturn |

| Greco-Roman deity | Helios-Sol | Selene-Luna | Ares-Mars | Hermes-Mercury | Zeus-Jupiter | Aphrodite-Venus | Cronus-Saturn |

| Greek: | ἡμέρα Ἡλίου | ἡμέρα Σελήνης | ἡμέρα Ἄρεως | ἡμέρα Ἑρμοῦ | ἡμέρα Διός | ἡμέρα Ἀφροδίτης | ἡμέρα Κρόνου |

| Latin: | dies Sōlis | dies Lūnae | dies Martis | dies Mercuriī | dies Iovis | dies Veneris | dies Saturnī |

| interpretatio germanica | Sun | Moon | Tiwaz | Wodanaz | Þunraz | Frige | — |

| Old English | sunnandæg | mōnandæg | tiwesdæg | wōdnesdæg | þunresdæg | frīgedæg | sæterndæg |

| Vedic Navagraha | Suryavara | Chandravara | Mangalavara | Budhavara | Bṛhaspativara | Shukravara | Shanivara |

An ecclesiastical, non-astrological, system of numbering the days of the week was adopted in Late Antiquity. This model also seems to have influenced (presumably via Gothic) the designation of Wednesday as "mid-week" in Old High German (mittawehha) and Old Church Slavonic (срѣда). Old Church Slavonic may have also modeled the name of Monday, понєдѣльникъ, after the Latin feria Secunda.[5] The ecclesiastical system became prevalent in Eastern Christianity, but in the Latin West it remains extant only in modern Icelandic, Galician, and Portuguese.[6]

| 1. Sunday (Christian Sabbath) | 2. Monday | 3. Tuesday | 4. Wednesday | 5. Thursday | 6. Friday | 7. Saturday (Jewish Sabbath) | |

| Greek | Κυριακὴ ἡμέρα /kiriaki iméra/ |

Δευτέρα ἡμέρα /devtéra iméra/ |

Τρίτη ἡμέρα /tríti iméra/ |

Τετάρτη ἡμέρα /tetárti iméra/ |

Πέμπτη ἡμέρα /pémpti iméra/ |

Παρασκευὴ ἡμέρα /paraskevi iméra/[7] |

Σάββατον /sáb:aton/ |

| Latin | [dies] dominica; rarely feria prima, feria dominica |

feria secunda | feria tertia | feria quarta; rarely media septimana |

feria quinta | feria sexta | Sabbatum; dies sabbatinus, dies Sabbati; rarely feria septima, feria Sabbati |

History

Ancient Near East

The earliest evidence of an astrological significance of a seven-day period is connected to Gudea, the priest-king of Lagash in Sumer during the Gutian dynasty, who built a seven-room temple, which he dedicated with a seven-day festival. In the flood story of the Assyro-Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh, the storm lasts for seven days, the dove is sent out after seven days, and the Noah-like character of Utnapishtim leaves the ark seven days after it reaches the firm ground. [lower-alpha 3]

Counting from the new moon, the Babylonians celebrated the 7th, 14th, 21st and 28th as "holy-days", also called "evil days" (meaning "unsuitable" for prohibited activities). On these days, officials were prohibited from various activities and common men were forbidden to "make a wish", and at least the 28th was known as a "rest-day".[11] On each of them, offerings were made to a different god and goddess.

In a frequently-quoted suggestion going back to the early 20th century,[12] the Hebrew Sabbath is compared to the Sumerian sa-bat "mid-rest", a term for the full moon. The Sumerian term has been reconstructed as rendered Sapattum or Sabattum in Babylonian, possibly present in the lost fifth tablet of the Enûma Eliš, tentatively reconstructed "[Sa]bbath shalt thou then encounter, mid[month]ly".[11]

It is possible that the Hebrew seven-day week is based on the Babylonian tradition, although going through certain adaptations. George Aaron Barton speculated that the seven-day creation account of Genesis is connected to the Babylonian creation epic, Enûma Eliš, which is recorded on seven tablets.[13]

Judea

A continuous seven-day cycle that runs throughout history without reference to the phases of the moon was first practiced in Judaism, dated to the 6th century BC at the latest.[14][15]

There are several hypotheses concerning the origin of the biblical seven-day cycle.

Friedrich Delitzsch and others suggested that the seven-day week being approximately a quarter of a lunation is the implicit astronomical origin of the seven-day week,[16] and indeed the Babylonian calendar used intercalary days to synchronize the last week of a month with the new moon.[17] According to this theory, the Jewish week was adopted from the Babylonians while removing the moon-dependency.

However, Niels-Erik Andreasen, Jeffrey H. Tigay, and others claimed that the Biblical Sabbath is mentioned as a day of rest in some of the earliest layers of the Pentateuch dated to the 9th century BC at the latest, centuries before Judea's Babylonian exile. They also find the resemblance between the Biblical Sabbath and the Babylonian system to be weak. Therefore, they suggested that the seven-day week may reflect an independent Israelite tradition.[18][19][20][21] Tigay writes:

It is clear that among neighboring nations that were in position to have an influence over Israel – and in fact which did influence it in various matters – there is no precise parallel to the Israelite Sabbatical week. This leads to the conclusion that the Sabbatical week, which is as unique to Israel as the Sabbath from which it flows, is an independent Israelite creation.[20][22]

The seven-day week seems to have been adopted, at different stages, by the Persian Empire, in Hellenistic astrology, and (via Greek transmission) in Gupta India and Tang China. [lower-alpha 4] The Babylonian system was received by the Greeks in the 4th century BC (notably via Eudoxus of Cnidus). However, the designation of the seven days of the week to the seven planets is an innovation introduced in the time of Augustus.[24] The astrological concept of planetary hours is rather an original innovation of Hellenistic astrology, probably first conceived in the 2nd century BC.[25]

The seven-day week was widely known throughout the Roman Empire by the 1st century AD,[24] along with references to the Jewish Sabbath by Roman authors such as Seneca and Ovid.[26] When the seven-day week came into use in Rome during the early imperial period, it did not immediately replace the older eight-day nundinal system.[27] The nundinal system had probably fallen out of use by the time Emperor Constantine adopted the seven-day week for official use in CE 321, making the Day of the Sun (dies Solis) a legal holiday.[28]

Achaemenid period

The Zoroastrian calendar follows the Babylonian in relating the 7th, 14th, 21st, and 28th of the month to Ahura Mazda.[29] The forerunner of all modern Zoroastrian calendars is the system used to determine dates in the Persian Empire, adopted from the Babylonian calendar by the 4th century BC.

Frank C. Senn in his book Christian Liturgy: Catholic and Evangelical points to data suggesting evidence of an early continuous use of a seven-day week; referring to the Jews during the Babylonian captivity in the 6th century BC,[15] after the destruction of the Temple of Solomon. While the seven-day week in Judaism is tied to Creation account in the Book of Genesis in the Hebrew Bible (where God creates the heavens and the earth in six days and rests on the seventh; Genesis 1:1–2:3, in the Book of Exodus, the fourth of the Ten Commandments is to rest on the seventh day, Shabbat, which can be seen as implying a socially instituted seven-day week), it is not clear whether the Genesis narrative predates the Babylonian captivity of the Jews in the 6th century BC. At least since the Second Temple period under Persian rule, Judaism relied on the seven-day cycle of recurring Sabbaths.[15]

Tablets from the Achaemenid period indicate that the lunation of 29 or 30 days basically contained three seven-day weeks, and a final week of eight or nine days inclusive, breaking the continuous seven-day cycle.[11] The Babylonians additionally celebrated the 19th as a special "evil day", the "day of anger", because it was roughly the 49th day of the (preceding) month, completing a "week of weeks", also with sacrifices and prohibitions.[11]

Difficulties with Friedrich Delitzsch's origin theory connecting Hebrew Shabbat with the Babylonian lunar cycle[30] include reconciling the differences between an unbroken week and a lunar week, and explaining the absence of texts naming the lunar week as Shabbat in any language.[31]

Hellenistic and Roman era

In Jewish sources by the time of the Septuagint, the term "Sabbath" (Greek Sabbaton) by synecdoche also came to refer to an entire seven-day week,[32] the interval between two weekly Sabbaths. Jesus's parable of the Pharisee and the Publican (Luke 18:12) describes the Pharisee as fasting "twice in the week" (Greek δὶς τοῦ σαββάτου dis tou sabbatou).

The ancient Romans traditionally used the eight-day nundinum but, after the Julian calendar had come into effect in 45 BC, the seven-day week came into increasing use. For a while, the week and the nundinal cycle coexisted, but by the time the week was officially adopted by Constantine in AD 321, the nundinal cycle had fallen out of use. The association of the days of the week with the Sun, the Moon and the five planets visible to the naked eye dates to the Roman era (2nd century).[33][15]

The continuous seven-day cycle of the days of the week can be traced back to the reign of Augustus; the first identifiable date cited complete with day of the week is 6 February AD 60, identified as a "Sunday" (as viii idus Februarius dies solis "eighth day before the ides of February, day of the Sun") in a Pompeiian graffito. According to the (contemporary) Julian calendar, 6 February 60 was, however, a Wednesday. This is explained by the existence of two conventions of naming days of the weeks based on the planetary hours system: 6 February was a "Sunday" based on the sunset naming convention, and a "Wednesday" based on the sunrise naming convention.[34]

China and Japan

The earliest known reference in Chinese writings to a seven-day week is attributed to Fan Ning, who lived in the late 4th century in the Jin Dynasty, while diffusions from the Manichaeans are documented with the writings of the Chinese Buddhist monk Yi Jing and the Ceylonese or Central Asian Buddhist monk Bu Kong of the 7th century (Tang Dynasty).

The Chinese variant of the planetary system was brought to Japan by the Japanese monk Kūkai (9th century). Surviving diaries of the Japanese statesman Fujiwara Michinaga show the seven-day system in use in Heian Period Japan as early as 1007. In Japan, the seven-day system was kept in use for astrological purposes until its promotion to a full-fledged Western-style calendrical basis during the Meiji Period (1868–1912).

India

The seven-day week was known in India by the 6th century, referenced in the Pañcasiddhāntikā. Shashi (2000) mentions the Garga Samhita, which he places in the 1st century BC or AD, as a possible earlier reference to a seven-day week in India. He concludes "the above references furnish a terminus ad quem (viz. 1st century) The terminus a quo cannot be stated with certainty".[35][36]

Arabia

In Arabia, a similar seven-day week system was adopted, which may have been influenced by the Hebrew week (via Christianity).

Christian Europe

The seven-day weekly cycle has remained unbroken in Christendom, and hence in Western history, for almost two millennia, despite changes to the Coptic, Julian, and Gregorian calendars, demonstrated by the date of Easter Sunday having been traced back through numerous computistic tables to an Ethiopic copy of an early Alexandrian table beginning with the Easter of AD 311.[37][38]

A tradition of divinations arranged for the days of the week on which certain feast days occur develops in the Early Medieval period. There are many later variants of this, including the German Bauern-Praktik and the versions of Erra Pater published in 16th to 17th century England, mocked in Samuel Butler's Hudibras. South and East Slavic versions are known as koliadniki (from koliada, a loan of Latin calendae), with Bulgarian copies dating from the 13th century, and Serbian versions from the 14th century.[39]

Medieval Christian traditions associated with the lucky or unlucky nature of certain days of the week survived into the modern period. This concerns primarily Friday, associated with the crucifixion of Jesus. Sunday, sometimes personified as Saint Anastasia, was itself an object of worship in Russia, a practice denounced in a sermon extant in copies going back to the 14th century.[40]

Sunday, in the ecclesiastical numbering system also counted as the feria prima or the first day of the week; yet, at the same time, figures as the "eighth day", and has occasionally been so called in Christian liturgy. [lower-alpha 5]

Justin Martyr wrote: "the first day after the Sabbath, remaining the first of all the days, is called, however, the eighth, according to the number of all the days of the cycle, and [yet] remains the first."[41]

A period of eight days, usually (but not always, mainly because of Christmas Day) starting and ending on a Sunday, is called an octave, particularly in Roman Catholic liturgy. In German, the phrase heute in acht Tagen (literally "today in eight days") means one week from today (i.e. on the same weekday). The same is true of the Italian phrase oggi otto (literally "today eight").

Week numbering

Weeks in a Gregorian calendar year can be numbered for each year. This style of numbering is often used in European and Asian countries. It is less common in the U.S. and elsewhere.

The ISO week date system

The system for numbering weeks is the ISO week date system, which is included in ISO 8601. This system dictates that each week begins on a Monday and is associated with the year that contains that week's Thursday.

Determining Week 1

In practice week 1 (W01 in ISO notation) of any year can be determined as follows:

- If January 1 falls on a Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday or Thursday, then the week of January 1 is Week 1.

- If January 1 falls on a Friday, Saturday, or Sunday however, then January 1 is considered to be part of the last week of the previous year and Week 1 will begin on the first Monday after January 1.

Examples:

- Week 1 of 2015 (2015W01 in ISO notation) started on Monday, 29 December 2014 and ended on Sunday, 4 January 2015, because 1 January 2015 fell on Thursday.

- Week 1 of 2021 (2021W01 in ISO notation) started on Monday, 4 January 2021 and will end on Sunday, 10 January 2021, because 1 January 2021 fell on Friday.

Week 52 and 53

It is also possible to determine if the last week of the previous year was Week 52 or Week 53 as follows:

- If January 1 falls on a Friday, then it is part of Week 53 of the previous year.

- If January 1 falls on a Saturday, then it is Week 52 in a common year, but Week 53 in a leap year.

- If January 1 falls on a Sunday, then it is part of Week 52 of the previous year.

Schematic representation of ISO week date

| Dominical letter(s)1 |

Days at the beginning of January | Effect1,2 | Days at the end of December1 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mon | 2 Tue | 3 Wed | 4 Thu | 5 Fri | 6 Sat | 7 Sun |

W01-13 | 01 Jan week | ... | 31 Dec week | 1 Mon4 | 2 Tue | 3 Wed | 4 Thu | 5 Fri | 6 Sat | 7 Sun | |

| G(F) | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 01 Jan | W01 | ... | W01 | 31 (30) | (31) | |||||

| F(E) | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 31 Dec | W01 | ... | W01 | 30 (29) | 31 (30) | (31) | |||||

| E(D) | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 30 Dec | W01 | ... | W01 (W53) | 29 (28) | 30 (29) | 31 (30) | (31) | |||||

| D(C) | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 29 Dec | W01 | ... | W53 | 28 (27) | 29 (28) | 30 (29) | 31 (30) | (31) | |||||

| C(B) | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 Jan | W53 | ... | W52 | 27 (26) | 28 (27) | 29 (28) | 30 (29) | 31 (30) | (31) | |||||

| B(A) | 01 | 02 | 03 Jan | W52 (W53) | ... | W52 | 26 (25) | 27 (26) | 28 (27) | 29 (28) | 30 (29) | 31 (30) | (31) | |||||

| A(G) | 01 | 02 Jan | W52 | ... | W52 (W01) | 25 (31) | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | ||||||

Notes

1. Parts in parentheses only apply when the year is a leap year.

2. Underlined parts belong to previous year or next year.

3. First date of the first week in the year.

4. First date of the last week in the year.

In some countries, though, the numbering system is different from the ISO standard. At least six numberings are in use:[42][43]

| System | First day of week |

First week of year contains | Can be last week of previous year |

Used by or in | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISO-8601 | Monday | 4 January | 1st Thursday | 4–7 days of year | yes | EU and most of other European countries, most of Asia and Oceania |

| (Middle Eastern) | Saturday | 1 January | 1st Friday | 1–7 days of year | yes | Much of the Middle East |

| (Western traditional) | Sunday | 1 January | 1st Saturday | 1–7 days of year | yes | Canada, United States, Iceland, Japan, Taiwan, Thailand, Hong Kong, Macau, Israel, Egypt, South Africa, the Philippines, and most of Latin America |

The semiconductor package date code is often a 4 digit date code YYWW where the first two digits YY are the last 2 digits of the calendar year and the last two digits WW are the two-digit week number.[44][45]

The tire date code mandated by the US DOT is a 4 digit date code WWYY with two digits of the week number WW followed by the last two digits of the calendar year YY.[46]

"Weeks" in other calendars

The term "week" is sometimes expanded to refer to other time units comprising a few days. Such "weeks" of between four and ten days have been used historically in various places.[47] Intervals longer than 10 days are not usually termed "weeks" as they are closer in length to the fortnight or the month than to the seven-day week.

Pre-modern calendars

Calendars unrelated to the Chaldean, Hellenistic, Christian, or Jewish traditions often have time cycles between the day and the month of varying lengths, sometimes also called "weeks".

An eight-day week was used in Ancient Rome and possibly in the pre-Christian Celtic calendar. Traces of a nine-day week are found in Baltic languages and in Welsh. The ancient Chinese calendar had a ten-day week, as did the ancient Egyptian calendar (and, incidentally, the French Republican Calendar, dividing its 30-day months into thirds).

A six-day week is found in the Akan Calendar. Several cultures used a five-day week, including the 10th century Icelandic calendar, the Javanese calendar, and the traditional cycle of market days in Korea. The Igbo have a "market week" of four days. Evidence of a "three-day week" has been derived from the names of the days of the week in Guipuscoan Basque.[48]

The Aztecs and Mayas used the Mesoamerican calendars. The most important of these calendars divided a ritual cycle of 260 days (known as Tonalpohualli in Nahuatl and Tzolk'in in Yucatec Maya) into 20 weeks of 13 days (known in Spanish as trecenas). They also divided the solar year into 18 periods (winal) of 20 days and five nameless days (wayebʼ), creating a 20-day month divided into four five-day weeks. The end of each five-day week was a market day.[49][50]

The Balinese Pawukon is a 210-day calendar consisting of 10 different simultaneously running weeks of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 days, of which the weeks of 4, 8, and 9 days are interrupted to fit into the 210-day cycle.

Modern calendar reforms

A 10-day week, called décade, was used in France for nine and a half years from October 1793 to April 1802; furthermore, the Paris Commune adopted the Revolutionary Calendar for 18 days in 1871.

The Bahá'í calendar features a 19-day period which some classify as a month and others classify as a week.[51]

The International Fixed Calendar (also known as the "Eastman plan") fixed every date always on the same weekday. This plan kept a 7-day week while defining a year of 13 months with 28 days each. It was the official calendar of the Eastman Kodak Company for decades.

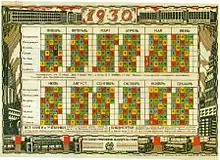

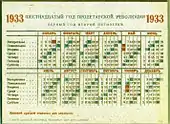

Five colors of five-day work week repeat.

Rest day of six-day work week in blue.

In the Soviet Union between 1929 and 1940, most factory and enterprise workers, but not collective farm workers, used five- and six-day work weeks while the country as a whole continued to use the traditional seven-day week.[52][53][54] From 1929 to 1951, five national holidays were days of rest (22 January, 1–2 May, 7–8 November). From autumn 1929 to summer 1931, the remaining 360 days of the year were subdivided into 72 five-day work weeks beginning on 1 January. Workers were assigned any one of the five days as their day off, even if their spouse or friends might be assigned a different day off. Peak usage of the five-day work week occurred on 1 October 1930 at 72% of industrial workers. From summer 1931 until 26 June 1940, each Gregorian month was subdivided into five six-day work weeks, more-or-less, beginning with the first day of each month. The sixth day of each six-day work week was a uniform day of rest. On 1 July 1935 74.2% of industrial workers were on non-continuous schedules, mostly six-day work weeks, while 25.8% were still on continuous schedules, mostly five-day work weeks. The Gregorian calendar with its irregular month lengths and the traditional seven-day week were used in the Soviet Union during its entire existence, including 1929–1940; for example, in the masthead of Pravda, the official Communist newspaper, and in both Soviet calendars displayed here. The traditional names of the seven-day week continued to be used, including "Resurrection" (Воскресенье) for Sunday and "Sabbath" (Суббота) for Saturday, despite the government's official atheism.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Week. |

Notes

- "ISO 8601 Data elements and interchange formats – Information interchange – Representation of dates and times" is an international standard covering the exchange of date- and time-related data.

- In pre-modern times, days were measured either from sunset to sunset, or from sunrise to sunrise so that the length of the week (and the day) would be subject to slight variations depending upon the time of year and the observer's geographical latitude.

- Copeland (1939) states as the date for Gudea "as early as 2600 BC";[8] the modern estimate according to the short chronology places Gudea in the 22nd century BC. By contrast, Anthony R. Michaelis claims that "the first great empire builder, King Sargon I of Akkad ([ruled] 2335 to 2279 BC [viz., middle chronology]), decreed a seven-day week in his empire. He lived for 56 years, established the first Semitic Dynasty, and defeated the Sumerian City-States. Thus the Akkadian language spread, it was adopted by the Babylonians, and the seven-day week was similarly inherited from him."[9] The number seven is significant in Sumerian mythology.[10]

- It was transmitted to China in the 8th century by Manichaeans, via the country of Kang (a Central Asian polity near Samarkand). Tang-era adoption is documented in the writings of the Chinese Buddhist monk Yi Jing and the Ceylonese Buddhist monk Bu Kong. According to the Chinese encyclopedia Cihai (辞海), there is some evidence that the system had been adopted twice, the first time already in the 4th century (Jin dynasty), based on a reference by a Jin era astrologer, Fan Ning (范寧 / 范宁). The Cihai under the entry for "seven luminaries calendar" (七曜曆 / 七曜历, qī yào lì) has: "method of recording days according to the seven luminaries [七曜 qī yào]. China normally observes the following order: Sun, Moon, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn. Seven days make one week, which is repeated in a cycle. Originated in ancient Babylon (or ancient Egypt according to one theory). Used by the Romans at the time of the 1st century AD, later transmitted to other countries. This method existed in China in the 4th century. It was also transmitted to China by Manichaeans in the 8th century from the country of Kang (康) in Central Asia."[23]

- This is just a reflection of the system of ordinal numbers in the Greek and Latin languages, where today is the "first" day, tomorrow the "second" day, etc. Compare the nundinal cycle (literally "nine-days" cycle, describing an eight-day week) of the Roman calendar, or the Resurrection of Jesus (after a period of less than 48 hours) being described (in texts derived from Latin) as happening on the "third day".

References

- sennight at worldwidewords.org (retrieved 12 January 2017)

- Richards, E. G. (2013). "Calendars". In S. E. Urban & P. K. Seidelmann, eds. Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac, 3rd ed. (pp. 585–624). Mill Valley, Calif.: University Science Books. 2013, pp. 592, 618. This is equivalent to saying that JD0, i.e. 1 January 4713 BC of the proleptic Julian calendar, was a Monday.

- E. G. Richards, Mapping Time, the Calendar and History, Oxford 1999. p. 269.

- "Territory Information". www.unicode.org. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- Max Vasmer, Russisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, s.v. понедельник; however, the Slavic languages later introduced a secondary numbering system that names Tuesday as the "second day".

- the latter specifically due to the influence of Martin of Braga, 6th-century archbishop of Braga. Richard A. Fletcher (1999). The Barbarian Conversion: From Paganism to Christianity. University of California Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-520-21859-8.McKenna, Stephen (1938). "Pagan Survivals in Galicia in the Sixth Century". Paganism and Pagan Survivals in Spain Up to the Fall of the Visigothic Kingdom. Catholic University of America. pp. 93–94. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- "day of preparation", i.e. the day before Sabbath, c.f. Luke 23:54 (καὶ ἡμέρα ἦν Παρασκευῆς, καὶ σάββατον ἐπέφωσκεν.)

- Copeland, Leland S. (1939). "Sources of the Seven-Day Week". Popular Astronomy. 47 (4): 176. Bibcode:1939PA.....47..175C.

- Michaelis, Anthony R. "The Enigmatic Seven" (PDF). Interdisciplinary Science Reviews. 7: 373.

- "The power of seven". The Economist. 20 December 2001.

- Pinches, T.G. (2003). "Sabbath (Babylonian)". In Hastings, James (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. 20. Selbie, John A., contrib. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 889–891. ISBN 978-0-7661-3698-4. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- "The Babylonian Sabbath". The American Antiquarian and Oriental Journal. Vol. XXX. 1908. p. 181. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- "Each account is arranged in a series of sevens, the Babylonian in seven tablets, the Hebrew in seven days. Each of them places the creation of man in the sixth division of its series." cited after Albert T. Clay, The Origin of Biblical Traditions: Hebrew Legends in Babylonia and Israel, 1923, p. 74.

- Zerubavel (1989), p. 11.

- Senn, Frank C. (1997). Christian Liturgy: Catholic and Evangelical. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-2726-3.

- Leland, S. Copeland (April 1939). "Sources of the Seven-Day Week". Popular Astronomy. XLVII (4): 176 ff. Bibcode:1939PA.....47..175C.

- A month consisted of three seven-day weeks and the fourth week of eight or nine days, thus breaking the seven-day cycle every month. Consequently, there is no evidence that the days of the week were given individual names in Babylonian tradition. Pinches, T.G. (2003). "Sabbath (Babylonian)". In Hastings, James (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. 20. Selbie, John A., contrib. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 889–891. ISBN 978-0-7661-3698-4. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- Andreasen, Niels-Erik A. (1972). The Old Testament Sabbath: A Tradition-historical Investigation. Society of Biblical Literature.

- Shafer, Byron E. (1974). "Reviewed Work: The Old Testament Sabbath: A Tradition-Historical Investigation by Niels-Erik A. Andreasen". Journal of Biblical Literature. 93 (2): 300–301. doi:10.2307/3263102. JSTOR 3263102.

- Tigay, Jeffery H. (1998). "Shavua". Mo'adei Yisra'el: Time and Holy Days in the Biblical and Second Commonwealth Periods (Heb.), Ed. Jacob S. Licht: 22–23.

- Hallo, William W. (1977). "New Moons and Sabbaths: A Case-Study in the Contrastive Approach". Hebrew Union College Annual. 48: 1–18. JSTOR 23506909.

- Friedman, Allen (September 2008). "Unnatural Time: Its History and Theological Significance". The Torah U-Madda Journal. 15: 104–105. JSTOR 40914729, Tigay's citation.

- "Japanese Days of the Week: the 'Seven Luminaries'". Days of the Week in Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese & Mongolian. cjvlang.

- Keegan, Peter; Sears, Gareth; Laurence, Ray (12 September 2013). Written Space in the Latin West, 200 BC to AD 300. A&C Black. ISBN 9781441123046.

- Zerubavel (1989), p. 14.

- So, Ky-Chun (6 April 2017). Jesus in Q: The Sabbath and Theology of the Bible and Extracanonical Texts. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781498282116.

- Brind'Amour, Pierre (1983). Le calendrier Romain :Recherches chronologiques (in French). Editions de l'Universitá d'Ottawa. pp. 256–275. ISBN 2760347028.

- Schaff, Philip (1884). History of the Christian Church Vol. III. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. p. 380. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- Boyce, Mary (ed. & trans.). Textual Sources for the Study of Zoroastrianism. University of Chicago Press, 1984, p. 19-20.

- Landau, Judah Leo. The Sabbath. Johannesburg, South Africa: Ivri Publishing Society, Ltd. pp. 2, 12. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- Sampey, John Richard (1915). "Sabbath: Critical Theories". In Orr, James (ed.). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Howard-Severance Company. p. 2630.

- Strong's Concordance, 4521.

- Zerubavel (1989), p. 45.

- Nerone Caesare Augusto Cosso Lentulo Cossil fil. Cos. VIII idus Febr(u)Arius dies solis, luna XIIIIX nun(dinae) Cumis, V (idus Februaries) nun(dinae) Pompeis.

Robert Hannah (2013). "Time in Written Spaces". In Peter Keegan; Gareth Sears; Ray Laurence (eds.). Written Space in the Latin West, 200 BC to AD 300. A&C Black. p. 89. - Shashi, Shyam Singh (2000). Encyclopaedia Indica India, Pakistan, Bangladesh Vol. 76 Major dynasties of ancient Orissa: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh. Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. pp. 114–115. ISBN 978-81-7041-859-7.

- Pandurang Vaman Kane (1930–1962). History of Dharmaśāstra.

- Neugebauer, Otto (1979). Ethiopic astronomy and computus. Verl. d. Österr. Akad. d. Wiss. ISBN 978-3-7001-0289-2.

- Jayne Lutwyche (22 January 2013). "Why are there seven days in a week?". Religion & Ethics. BBC.

The Roman context of the spread of Christianity meant that Rome contributed a lot to the structure and calendar of the new faith

- William Francis Ryan, The Bathhouse at Midnight: An Historical Survey of Magic and Divination in Russia, Penn State Press, 1999 p. 380.

- William Francis Ryan, The Bathhouse at Midnight: An Historical Survey of Magic and Divination in Russia, Penn State Press, 1999 p. 383.

- Peter Kirby. "Saint Justin Martyr: Dialogue with Trypho". Early Christian Writings.

- Peter Johann Haas (26 January 2002). "Weeknumber sorted by definition". pjh2.de.

- "Calendar Weeks". J. R. Stockton. Archived from the original on 13 January 2014.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- "Quality & Lead-free (Pb-free): Marking Convention". Texas Instrument. Archived from the original on 5 April 2014.

- "Top Mark Convention – 4-Digit Date Code". Fairchild Semiconductor. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014.

- "49 CFR 574.5 – Tire identification requirements". Legal Information Institute.

- OED s.v. "week n.", entry 1.c.: "Sometimes applied transf. to other artificial cycles of a few days that have been employed various peoples"

- Astronomy and Basque Language, Henrike Knörr, Oxford VI and SEAC 99 "Astronomy and Cultural Diversity", La Laguna, June 1999. It references Alessandro Bausani, 1982, The prehistoric Basque week of three days: archaeoastronomical notes, The Bulletin of the Center for Archaeoastronomy (Maryland), v. 2, 16–22. 1. astelehena ("week-first", Monday), 2. asteartea ("week-between", Tuesday), 3. asteazkena ("week-last", Wednesday).

- Zerubavel (1989), pp. 50–54.

- "Aztec calendar stone". aztec-history.com.

- Zerubavel, Eviatar (1985). The Seven-Day Circle. New York: The Free Press. pp. 48–50. ISBN 0029346800.

- Foss, Clive (September 2004). "Stalin's topsy-turvy work week". History Today. 54 (9): 46–47.

- "La réforme en Russie: il faudra attendre… plus de trois siècles" [The reform in Russia: it will be necessary to wait… more than three centuries]. iCalendrier (in French).

- Zerubavel, Eviatar (1985). "The Soviet five-day Nepreryvka". The Seven Day Circle. New York: Free Press. pp. 35–43. ISBN 0029346800.

- Zerubavel, Eviatar (1989). The Seven Day Circle: The History and Meaning of the Week. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-98165-9.

Further reading

- Colson, Francis Henry (1926). The Week: An Essay on the Origin and Development of the Seven-day Cycle. Cambridge University Press. OCLC 59110177.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.