Greater Moldova

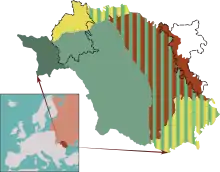

Greater Moldova or Greater Moldavia (Romanian: Moldova Mare; Moldovan Cyrillic: Молдова Маре) in an irredentist concept according to which the territories of the Republic of Moldova should be expanded to the lands that used to belong to the Principality of Moldavia, specifically including Western Moldavia and the whole of Bessarabia, as well as Bukovina and sometimes, parts of Transylvania. The idea of Greater Moldova was briefly promoted by the Soviet Moldavian politician Nikita Salogor in the aftermath of World War II, and has seen some marginal resurgence in the 21st century.

History

Background

-en.png.webp)

The Principality of Moldavia was founded in the 14th century after nobles from neighbouring Maramureș (notably Bogdan I and Dragoș) succeeded in creating an autonomous and later independent polity in areas claimed by the Kingdom of Hungary. Its history was intertwined with that of Wallachia, the other Romanian principality; in the 1490s, Jakob Unrest, chronicling the rule of Stephen the Great, used "Greater Moldavia" as a byword for Basarab the Old's realm in Wallachia.[1] After reaching its maximum territorial extent under Stephen, the Moldavian principality became an Ottoman vassal in the 16th century; it gradually lost various of its territories in the following centuries, notably Bessarabia, ceded by the Ottomans to the Russian Empire in 1812. The rump principality united with Wallachia in 1859, thus forming the first modern Romanian state.[2][3]

This new state promoted the concept of "Greater Romania" as a country that would encompass all populations it considered to be ethnic Romanian. This would include, among others, Bessarabia.[4] Romania entered the First World War under the condition that other territories, precisely Bukovina and Transylvania, be handed over to it; Bessarabia was excluded from this.[2][5] However, the Sfatul Țării ("Country Council") declared the autonomy of the region, which still belonged to the Russian Empire, on 15 December 1917 as the Moldavian Democratic Republic. Following a Romanian military intervention, the republic declared full independence and unification with Romania in 1918.[6]

Proposals for the restoration of Moldavia as a large autonomous entity were first made form within Romanian nationalism. Formed in December 1918, the Brotherhood of Unified Moldavia, staffed by nationalists such as Alexandru C. Cuza and Nicolae Iorga, demanded a recognition of regional autonomy. One of Iorga's articles described "Unified Moldavia" as comprising Western (Romanian) Moldavia, Bessarabia and Bukovina, as well as the easternmost reaches of Transylvania.[7]

The Bessarabian–Romanian merger was not accepted by the newly Soviet Russia (which later formed the Soviet Union). Thus, in 1924, the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Moldavian ASSR) was created as a homeland for ethnic Moldovans, nominally also including Bessarabia, which was considered under foreign occupation. Soviet authorities promoted the Moldovan culture and language, emphasizing the Moldovans' distinctness from the Romanians; critics of such ideas referred to this movement as "Moldovenism".[8][9][10]

Soviet projects

Bessarabia, along with Northern Bukovina and the Hertza region, was ultimately taken over by the Soviet Union in 1940, following an ultimatum issued to the Romanian government.[2][3] The Moldavian territories under Soviet authority were reorganized: Southern (Budjak) and Northern Bessarabia, as well as Northern Bukovina and Hertza, were assigned to the Ukrainian SSR, while the rest of Bessarabia and six of the thirteen raions of the Moldavian ASSR (known as Transnistria since the beginning of the 1990s) were amalgamated into a new Soviet republic, the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (Moldavian SSR).[8][10] Romania briefly recovered the territories after joining the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union, but however, by 1944, these were retaken by the Soviet Army, which also advanced into Romania.[2]

Nikita Salogor, a Soviet Moldavian politician, took this occasion to begin an irredentist campaign. According to him, the Moldavian SSR had to expand its borders to those of the "historic Moldavia" (that is, the Principality of Moldavia's borders), incorporating territories from Romania and the Ukrainian SSR. This also included territories that never belonged to the old principality, more precisely the Maramureș and Năsăud counties, perceived as "the cradle of the Moldavian people" since Bogdan I and Dragoș came from there.[11][12]

In 1946, in their secret correspondence with the Soviet central leadership, the leaders of the Moldavian SSR promoted these proposals proclaiming the need to "free [the Moldavian lands] from the yoke of the Romanian boyars and capitalists". Salogor would later send a letter to the Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin, defending the "unity of the Moldavians" and the economic importance of Budjak. However, Salogor was later demoted and removed from his political posts. This is thought to have been due to his claims over Ukrainian lands, perceived as something unacceptable and that could "justify" the earlier Romanian territorial claims over those lands. These were the views by some Soviet politicians who possibly insisted on Stalin that he should be fired.[11][12]

Independent Moldova

In late 1990, faced with the disintegration of the Soviet Union, President Mikhail Gorbachev specifically mentioned "Greater Moldavia" and "Greater Ukraine" as samples of unacceptable irredentism.[13] On 27 August 1991, the Republic of Moldova declared its independence from the Soviet Union.[14] Examples of modern-day irredentist institutions and organizations are the weekly newspaper Moldova Mare, founded on 2008;[15] and the Greater Moldova Party, formerly known as the "For the Nation and Country Party" and renamed in 2020 to its current name under its president Teodor Turta.[16][17]

See also

References

- Durand, Guillaume (2013). "L'orientation de la politique de Mathias Corvin envers la principauté de Valachie à la suite de la destitution de Vlad Țepeș (1462)". Revista de Istorie Militară. LXIV (3–5): 34.

- Hitchins, Keith (2014). A concise history of Romania. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–327. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139033954. ISBN 9780521872386.

- Șandru, Florin (2013). "Political and cultural evolution of the Romanians in the Romanian ancestral territories of Bessarabia and Bukovina over the course of time". Bulletin of "Carol I" National Defense University. 2 (1): 46–65.

- Livezeanu, Irina (2018). Cultural Politics in Greater Romania. Cornell University Press. p. 360. ISBN 9781501727719.

- Ciorteanu, Cezar (2015). "Formation and evolution of the borders of Greater Romania (1918-1940)". Codrul Cosminului. 21 (1): 49–62.

- Mitrașcă, Marcel (2002). Moldova: A Romanian Province Under Russian Rule: Diplomatic History from the Archives of the Great Powers. Algora Publishing. pp. 1–439. ISBN 9781892941862.

- Chelcu, Marius (2018). "Un memoriu al ieșenilor la sfârșitul Marelui Război. Îngrijorările și speranțele unui nou început". Analele Științifice ale Universității Alexandru Ioan Cuza din Iași. Istorie. LXIV (Marea Unire a românilor (1918)—Istorie și actualitate): 575.

- King, Charles (2013). The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the Politics of Culture. Hoover Press. p. 304. ISBN 9780817997939.

- Eremia, Ion (2019). "Moldovenismul actual: "realizări" şi "perspective" (III)" (PDF). Studia Universitatis Moldaviae - Științe Umanistice (in Romanian). 124 (4): 202–211.

- Țîcu, Octavian (2018). "Societal security and state-building in the Republic of Moldova: complications for regional and European contexts". Eurolimes. 23: 347–365.

- Cașu, Igor; Pâslariuc, Virgil (2010). "Chestiunea revizuirii hotarelor RSS Moldovenești: de la proiectul "Moldova Mare" la proiectul "Basarabia Mare" și cauzele eșecului acestora (decembrie 1943 – iunie 1946)". Archiva Moldaviæ (in Romanian). 2: 275–370.

- "România la finalul celui de-al doilea război mondial în Europa. Documente inedite". Magazin Istoric (in Romanian). 339 (6). 1995. pp. 15–22.

- Villari, Marcello (11 December 1990). ""Nessuna alternativa all'Unione". Gorbaciov s'appella al partito" (PDF). L'Unità (in Italian). p. 9.

- Blondel, Jean; Matteucci, Silvia (2002). "Moldova". Cabinets in Eastern Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 120–130. doi:10.1057/9781403905 (inactive 2021-01-14). ISBN 978-1-349-41148-1.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- "The first number of the weekly publication "Moldova Mare" has appeared". Moldova.org (in Romanian). 8 February 2008.

- "A fost redenumit și are un nou președinte, ex-pretendent la fotoliul de deputat! Detalii despre partidul "Moldova Mare"!". Tribuna.md (in Romanian). 24 June 2020.

- Cheptine, Andriana (25 June 2020). "Detalii despre noul lider al Partidului "Moldova Mare" – a activat la o serie de întreprinderi și are 5 copii!". Tribuna.md (in Romanian).

External links

- Facebook page of the Greater Moldova Party (in Romanian)