Unionism in the United Kingdom

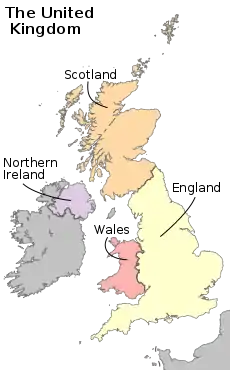

Unionism in the United Kingdom, also referred to as British unionism, is a political ideology favouring the continued unity of England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland as one sovereign state, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Those who support the union are referred to as "Unionists".[1] British unionism is closely associated with British nationalism, which asserts that the British are a nation and promotes the cultural unity of Britons,[2][3]in a definition of Britishness that may include people of English, Scottish, Welsh, Irish and Cornish descent (those living in both Northern Ireland and Great Britain and historically the whole of Ireland when it was within the United Kingdom).

In the lead up to the American War of Independence in the second half of the 18th century, there existed British loyalists and colonial rebels (Whigs or Patriots). None of the Loyalists wanted separation. Not even a majority amongst the Rebels necessarily desired to be separate from Great Britain.

Later, towards the end of the 19th century, Irish Unionism was by and large a reaction to an increase in separatist Irish nationalist agitation or self governance in Home Rule. Most of Ireland became separated from the UK in the 1920s. In Northern Ireland the polarised constitutional ideologies of republicans and loyalists has led to violent conflict, known as the Troubles.

Since the late 20th century differing views on the constitutional status of the countries within the UK has become a bigger issue in Scotland and Wales. Following the Scottish National Party's victory in Scotland's 2011 election, a referendum on Scottish independence took place on 18 September 2014: the result supported remaining within the United Kingdom, winning the vote by 55.3% No to 44.7% Yes to the question "Should Scotland be an independent country?".

Formation of the Union

The Kingdom of Great Britain was formed on 1 May 1707 through the Acts of Union 1707, two simultaneous acts passed by the parliaments of England and Scotland. These created a political union between the Kingdom of England (consisting of England and Wales) and the Kingdom of Scotland. This event was the result of the Treaty of Union that was agreed on 22 July 1706.[4]

The Acts created a single Parliament of Great Britain at Westminster as well as a customs and monetary union. However, England and Scotland remained separate legal jurisdictions.

In 1801, the Acts of Union 1800 united the Kingdom of Great Britain with the Kingdom of Ireland, through two similar independent acts of the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of Ireland. This created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland on a similar basis to how England and Scotland had been united a century earlier.

A campaign to repeal the Union in Ireland began immediately. A series of efforts in the late 19th and early 20th century to establish Home Rule for Ireland within the union were unsuccessful and, following the Anglo-Irish War and subsequent Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1922, most of Ireland left the union as the Irish Free State. Northern Ireland remained part of the union and the United Kingdom became known formally as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in 1927 (see: Partition of Ireland).

Prior to the creation of the Kingdom of Great Britain, the three kingdoms had been separate states in personal union. When James VI of Scotland succeeded his cousin, Elizabeth I of England, as king of England, the crowns of England, Ireland and Scotland were united.

Before then, in 1542, the crowns of England and Ireland had been united through the creation of the Kingdom of Ireland under the Crown of Ireland Act 1542. Since the 12th century, the King of England had acted as Lord of Ireland, under papal overlordship. The act of 1542 created the title of King of Ireland for King Henry VIII of England and his successors, removing the role of the Pope as ultimate overlord of Ireland.

Support for the Union

Support for the Union was historically highest in England and lowest in Ireland, with significant anti-Union movements in Scotland and Wales. Today, polls consistently show that a majority of people in England and Wales support the continuation of the Union, however in Scotland support for independence has regularly polled higher than support for the union.[5] Since the widespread devolution of the late 1990s, the electorate of Scotland and Wales had been more likely to vote for nationalist political parties for local or regional elections than in general elections for the House of Commons, where support for the UK-wide parties dominated. However, for Scotland, after the 2015 United Kingdom general election this is no longer the case with the SNP returning 56 and out of 59 MPs. In England, English nationalist parties have never won a seat in Parliament.

In 2014, the extent of UK-wide support for the Union came under considerable investigation as a result of the prospect of Scottish independence. The final result of the referendum saw a majority of Scottish voters electing to remain in the Union, with 55.3% voting against independence.[6] Polls conducted in 2014 found that 70% of voters in England opposed Scottish independence,[7] as did 83% of the Welsh population.[8]

The Scottish referendum prompted an increase in political activity and vocalism across the United Kingdom. Several hundred celebrities, business leaders and political figures signed open letters to the national media supporting the Union and opposing Scottish independence,[9][10] while large pro-Union rallies were held in several British cities, including in Trafalgar Square.[11]

Although support for independence declined and/or stagnated generally between 2015 and 2018, it started to increase towards the end of 2019. Independence was leading over Union support in most polls for each month of 2020 up to July. On 6th July 2020, Professor Sir John Curtice stated that "support for the Union [in Scotland] has never been weaker". [12]

In Northern Ireland, support for the Union has been found to increase since the end of The Troubles, especially within the Roman Catholic population.[13] In part, this is as a result of a decreasing association of the Union with radical or extremist political ideologies following the Good Friday Agreement.

Political parties and other groups

The following is a list of active political parties and organisations who support the union.

- Major, Great Britain-wide parties

- Conservative and Unionist Party

- Labour Party

- Liberal Democrats

- Reform UK[14]

- UK Independence Party (UKIP)[15]

- Northern Ireland parties

- Democratic Unionist Party (DUP)

- Progressive Unionist Party (PUP)

- Traditional Unionist Voice (TUV)

- Ulster Unionist Party (UUP)

- UKIP and the Conservatives also stand in Northern Ireland

- Parties in British Overseas Territories

- Minor parties

- Britain First[17]

- British Freedom Party (BFP)

- British National Party (BNP)[18]

- British People's Party (BPP)[19]

- British Union & Sovereignty Party (BUSP)

- National Front (NF)[20]

- Respect Party[21]

- Scottish Unionist Party (SUP)

- More United

- Militant and other groups

See also

References

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/home_rule_movement_01.shtml

- Motyl, Alexander J. (2001). Encyclopedia of Nationalism, Volume II. Academic Press. pp. 62–63. ISBN 0-12-227230-7.

- Guntram H. Herb, David H. Kaplan. Nations and Nationalism: A Global Historical Overview: A Global Historical Overview. Santa Barbara, California, USA: ABC-CLIO, 2008.

- "Articles of Union with Scotland 1707". www.parliament.uk. Retrieved 19 October 2008.

- Opinion polling on Scottish independence

- BBC News, 'Scotland Decides' (September 2014) https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/events/scotland-decides

- Populus poll for the Daily Mail, reported on Georgia Newsday (09/12/2014) "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Sky News, Scot Vote Boosts Welsh Independence Support (15 September 2014) http://news.sky.com/story/1336172/scot-vote-boosts-welsh-independence-support

- Euro Weekly News, 'Scottish Independence Opposed by Celebrities' (7 August 2014) https://www.euroweeklynews.com/news/uk/item/121924-scottish-independence-opposed-by-celebrities

- Reuters, 'Business leaders urge Scots to vote against independence' (27 August 2014) http://uk.reuters.com/article/2014/08/27/uk-scotland-independence-business-idUKKBN0GR04820140827

- 'Scottish independence: thousands attend Trafalgar Square rally urging Scots to vote 'No' in referendum', London Evening Standard (15 September 2014) https://www.standard.co.uk/news/london/trafalgar-square-rally-eddie-izzard-and-sir-bob-geldof-lead-pleas-for-scotland-to-stay-in-uk-9734619.html

- https://www.thenational.scot/news/18562858.john-curtice-support-union-never-weaker/

- BBC News, 'Do more Northern Ireland Catholics now support the Union?' (29 November 2012) https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-20547143

- https://reformuk.scot/

- Mark Aitken (12 May 2013). "UKIP leader Nigel Farage insists he will play a key role in the campaign against Scottish independence". Daily Record. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- http://www.gsd.gi/leader-of-the-opposition-post-referendum-parliamentary-address/

- Britain First official website. Statement of Principles Archived 9 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. "Britain First is a movement of British Unionism. We support the continued unity of the United Kingdom whilst recognising the individual identity and culture of the peoples of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. We abhor and oppose all trends that threaten the integrity of the Union". Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- British National Party website. The SNP. A real nationalist party? Archived 7 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- "Stand by Loyal Ulster!" – British People's Party leaflet. Official British People's Party website. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- British National Front website. What we stand for. "We stand for the continuation of the UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND – Four Countries, One Nation. Scotland, Ulster, England and Wales, united under our Union Flag – we will never allow the traitors to destroy our GREAT BRITAIN!". Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- Respect Party website. Scotland Archived 27 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. "Respect officially passed a motion at its 2014 AGM backing a ‘No’ vote in Scotland’s Independence Referendum in September". Retrieved 8 July 2014.

Further reading

- Armitage, David (2000). The Ideological Origins of the British Empire (reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78978-3.

- Brockliss, L. W. B. (1997). Brockliss, L. W. B.; Eastwood, David (eds.). A Union of Multiple Identities: The British Isles, C1750-c1850 (illustrated ed.). Manchester University Press ND. ISBN 978-0-7190-5046-6.

- Cochrane, Feargal (2001). Unionist Politics and the Politics of Unionism Since the Anglo-Irish Agreement (2, revised ed.). Cork University Press. ISBN 978-1-85918-259-8.

- English, Richard (1996). English, Richard; Walker, Graham S. (eds.). Unionism in Modern Ireland: New Perspectives on Politics and Culture. Macmillan Press. ISBN 978-0-312-15979-5.

- Hazell, Robert (2006). Hazell, Robert (ed.). The English Question. Devolution Series (illustrated, annotated ed.). Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-7369-4.

- Jackson, Alvin (2011). The Two Unions: Ireland, Scotland, and the Survival of the United Kingdom, 1707–2007 (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-959399-6.

- Kanter, Douglas (2009). The making of British unionism, 1740–1848: politics, government, and the Anglo-Irish constitutional relationship. Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-84682-160-8.

- Kearney, Hugh F. (2006). The British Isles: A History of Four Nations (2, illustrated, revised, reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84600-4.

- Kendle, John (1992). Walter Long, Ireland and the Union, 1905–1920. McGill-Queens. ISBN 978-0-7735-0908-5.

- Nicholls, Andrew D. (1999). The Jacobean Union: A Reconsideration of British Civil Policies Under the Early Stuarts. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-30835-2.

- O'Day, Alan; Boyce, David George (2001). Defenders of the Union: A Survey of British and Irish Unionism Since 1801. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-17421-3.

- Ward, Paul (2005). Unionism in the United Kingdom, 1918–1974. Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-3827-5.

.svg.png.webp)