Iraqi Kurdistan

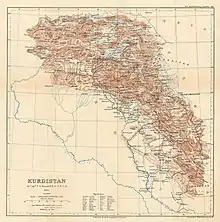

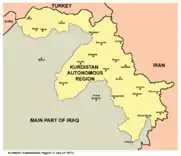

Iraqi Kurdistan or Southern Kurdistan[1] (Kurdish: باشووری کوردستان ,Başûrê Kurdistanê,[2][3][4]) is the part of Kurdistan in northern Iraq. It is one of the four parts of Kurdistan, which also includes parts of southeastern Turkey (Northern Kurdistan), northern Syria (Western Kurdistan), and northwestern Iran (Eastern Kurdistan).[5][6] Much of the geographical and cultural region of Iraqi Kurdistan is part of the Kurdistan Region (KRI), an autonomous region recognized by the Constitution of Iraq.[7]

Etymology

The exact origins of the name Kurd are unclear. The suffix -stan (Persian: ـستان, translit. stân) is Persian for region. The literal translation for Kurdistan is "Region of Kurds.”

"Kurdistan" was also formerly spelled Curdistan.[8][9] One of the ancient names of Kurdistan is Corduene.[10][11]

Geography

Southern Kurdistan is largely mountainous, with the highest point being a 3,611 m (11,847 ft) point known locally as Cheekha Dar ("black tent"). Mountains in Iraqi Kurdistan include the Zagros, Sinjar Mountains, Hamrin Mountains, Mount Nisir and Qandil mountains. There are many rivers running through the region, which is distinguished by its fertile lands, plentiful water, and picturesque nature. The Great Zab and the Little Zab flow east-west in the region. The Tigris river enters Iraqi Kurdistan from Turkish Kurdistan.

The mountainous nature of Iraqi Kurdistan, the difference of temperatures in its various parts, and its wealth of waters make it a land of agriculture and tourism. The largest lake in the region is Lake Dukan. There are also several smaller lakes, such as Darbandikhan Lake and Duhok Lake. The western and southern parts of Iraqi Kurdistan are not as mountainous as the east. Instead, it is rolling hills and plains vegetated by sclerophyll scrubland.

Ecology

Vegetation in the region includes, Abies cilicica, Quercus calliprinos, Quercus brantii, Quercus infectoria, Quercus ithaburensis, Quercus macranthera, Cupressus sempervirens, Platanus orientalis, Pinus brutia, Juniperus foetidissima, Juniperus excelsa, Juniperus oxycedrus, Salix alba, Olea europaea, Ficus carica, Populus euphratica, Populus nigra, Crataegus monogyna, Crataegus azarolus, cherry plum, rose hips, pistachio trees, pear and Sorbus graeca. The desert in the south is mostly steppe and would feature xeric plants such as palm trees, tamarix, date palm, fraxinus, poa, white wormwood and chenopodiaceae.[12][13]

Animals found in the region include the Syrian brown bear, wild boar, gray wolf, golden jackal, Indian crested porcupine, red fox, goitered gazelle, Eurasian otter, striped hyena, Persian fallow deer, onager, mangar and the Euphrates softshell turtle.[14]

Bird species include, the see-see partridge, Menetries's warbler, western jackdaw, Red-billed chough, hooded crow, European nightjar, rufous-tailed scrub robin, masked shrike and the pale rockfinch.[15][16]

Climate

Due to its latitude and altitude, Iraqi Kurdistan is cooler and much wetter than the rest of Iraq. Most areas in the region fall within the Mediterranean climate zone (Csa), with areas to the southwest being semi-arid (BSh). Due to the summers being less extreme, thousands of tourists from the hotter parts of Iraq come to visit the region in that season.[17]

Average summer temperatures range from 35 °C (95 °F) in the cooler northernmost areas to blistering 40 °C (104 °F) in the southwest, with lows around 21 °C (70 °F) to 24 °C (75 °F). Winters, however, are dramatically cooler than the rest of Iraq, with highs averaging between 9 °C (48 °F) and 11 °C (52 °F) and with lows hovering around 3 °C (37 °F) in some areas and freezing in others, dipping to −2 °C (28 °F) and 0 °C (32 °F) on average.

Among other cities in the climate table below, Soran, Shaqlawa and Halabja also experience lows which average below 0 °C (32 °F) in winter. Duhok has the hottest summers in the region, with highs averaging around 42 °C (108 °F). Annual rainfall differs across Iraqi Kurdistan, with some places seeing rainfall as low as 500 millimetres (20 in) in Erbil to as high as 900 millimetres (35 in) in places like Amadiya. Most of the rain falls in winter and spring, and is usually heavy. Summer and early autumn are virtually dry, and spring is fairly tepid. Iraqi Kurdistan sees snowfall occasionally in the winter, and frost is common. There is a seasonal lag in some places in summer, with temperatures peaking around August and September.

| Climate data for Erbil | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20 (68) |

27 (81) |

30 (86) |

34 (93) |

42 (108) |

44 (111) |

48 (118) |

49 (120) |

45 (113) |

39 (102) |

31 (88) |

24 (75) |

49 (120) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12.4 (54.3) |

14.2 (57.6) |

18.1 (64.6) |

24.0 (75.2) |

31.5 (88.7) |

38.1 (100.6) |

42.0 (107.6) |

41.9 (107.4) |

37.9 (100.2) |

30.7 (87.3) |

21.2 (70.2) |

14.4 (57.9) |

27.2 (81.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 7.4 (45.3) |

8.9 (48.0) |

12.4 (54.3) |

17.5 (63.5) |

24.1 (75.4) |

29.7 (85.5) |

33.4 (92.1) |

33.1 (91.6) |

29.0 (84.2) |

22.6 (72.7) |

15.0 (59.0) |

9.1 (48.4) |

20.2 (68.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.4 (36.3) |

3.6 (38.5) |

6.7 (44.1) |

11.1 (52.0) |

16.7 (62.1) |

21.4 (70.5) |

24.9 (76.8) |

24.4 (75.9) |

20.1 (68.2) |

14.5 (58.1) |

8.9 (48.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

13.2 (55.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −4 (25) |

−6 (21) |

−1 (30) |

3 (37) |

6 (43) |

10 (50) |

13 (55) |

17 (63) |

11 (52) |

4 (39) |

−2 (28) |

−2 (28) |

−6 (21) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 111 (4.4) |

97 (3.8) |

89 (3.5) |

69 (2.7) |

26 (1.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

12 (0.5) |

56 (2.2) |

80 (3.1) |

540 (21.2) |

| Average rainy days | 9 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 62 |

| Average snowy days | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74.5 | 70 | 65 | 58.5 | 41.5 | 28.5 | 25 | 27.5 | 30.5 | 43.5 | 60.5 | 75.5 | 50.0 |

| Source 1: Climate-Data.org,[18] My Forecast for records, humidity, snow and precipitation days[19] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: What's the Weather Like.org,[20] Erbilia[21] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Barzan | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.0 (48.2) |

10.5 (50.9) |

14.7 (58.5) |

20.6 (69.1) |

27.8 (82.0) |

34.5 (94.1) |

38.7 (101.7) |

38.8 (101.8) |

34.8 (94.6) |

27.4 (81.3) |

17.9 (64.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

23.8 (74.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.3 (39.7) |

5.5 (41.9) |

9.4 (48.9) |

14.8 (58.6) |

21.1 (70.0) |

26.9 (80.4) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.8 (87.4) |

26.6 (79.9) |

20.0 (68.0) |

12.3 (54.1) |

6.3 (43.3) |

17.4 (63.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.3 (31.5) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

4.2 (39.6) |

9.0 (48.2) |

14.4 (57.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

23.2 (73.8) |

22.8 (73.0) |

18.4 (65.1) |

12.7 (54.9) |

6.7 (44.1) |

1.7 (35.1) |

11.0 (51.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 151 (5.9) |

172 (6.8) |

150 (5.9) |

114 (4.5) |

37 (1.5) |

1 (0.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.0) |

19 (0.7) |

88 (3.5) |

106 (4.2) |

839 (33) |

| Source: Climate-Data[22] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Batifa | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.7 (45.9) |

9.4 (48.9) |

13.7 (56.7) |

19.1 (66.4) |

26.3 (79.3) |

33.3 (91.9) |

37.7 (99.9) |

37.5 (99.5) |

33.2 (91.8) |

25.3 (77.5) |

16.8 (62.2) |

9.8 (49.6) |

22.5 (72.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.6 (30.9) |

0.3 (32.5) |

3.7 (38.7) |

8.1 (46.6) |

13.2 (55.8) |

18.2 (64.8) |

22.2 (72.0) |

21.7 (71.1) |

17.6 (63.7) |

11.8 (53.2) |

6.2 (43.2) |

1.5 (34.7) |

10.3 (50.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 124 (4.9) |

144 (5.7) |

132 (5.2) |

107 (4.2) |

51 (2.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.0) |

29 (1.1) |

84 (3.3) |

123 (4.8) |

795 (31.2) |

| Source: Climate-Data[23] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Amadiya | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.2 (43.2) |

7.8 (46.0) |

12.1 (53.8) |

17.8 (64.0) |

25.1 (77.2) |

31.9 (89.4) |

36.3 (97.3) |

36.2 (97.2) |

32.2 (90.0) |

24.4 (75.9) |

15.4 (59.7) |

8.4 (47.1) |

21.2 (70.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −2.4 (27.7) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

2.4 (36.3) |

7.2 (45.0) |

12.5 (54.5) |

17.4 (63.3) |

21.4 (70.5) |

20.9 (69.6) |

16.8 (62.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

5.0 (41.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

9.2 (48.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 126 (5.0) |

176 (6.9) |

156 (6.1) |

128 (5.0) |

56 (2.2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.0) |

32 (1.3) |

96 (3.8) |

126 (5.0) |

897 (35.3) |

| Average precipitation days | 7 | 6 | 10 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 60 |

| Source 1: World Weather Online (precipitation days)[24] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Climate-Data (temperatures and rainfall amount)[25] | |||||||||||||

History

Pre-Islamic period

In prehistoric times, the region was home to a Neanderthal culture such as has been found at the Shanidar Cave. The region was host to the Jarmo culture circa 7000 BC. The earliest neolithic site in Kurdistan is at Tell Hassuna, the centre of the Hassuna culture, circa 6000 BC. The region was inhabited by the northern branch of the Gutian/Hurrians around 2400 BC.

It was ruled by the Akkadian Empire from 2334 BC until 2154 BC. Assyrian kings are attested from the 23rd century BC according to the Assyrian King List, and Assyrian city-states such as Ashur and Ekallatum started appearing in the region from the mid-21st century BC. Prior to the rule of king Ushpia circa 2030 BC, the city of Ashur appears to have been a regional administrative center of the Akkadian Empire, implicated by Nuzi tablets,[26] subject to their fellow Akkadian Sargon and his successors.[27]

Large cities were built by the Assyrians, including Ashur, Nineveh, Guzana, Arrapkha, Imgur-Enlil (Balawat), Shubat-Enlil and Kalhu (Calah / Nimrud). One of the major Assyrian cities in the area, Erbil (Arba-Ilu), was noted for its distinctive cult of Ishtar,[28] and the city was called "the Lady of Ishtar" by its Assyrian inhabitants.[29] The Assyrians ruled the region from the 21st century BC.

The region was known as Assyria, and was the center of various Assyrian empires (particularly during the periods 1813–1754 BC, 1385–1076 BC and the Neo Assyrian Empire of 911–608 BC. Between 612 and 605 BC, the Assyrian empire fell and it passed to the neo-Babylonians and later became part of the Athura Satrap within the Achaemenian Empire from 539 to 332 BC, where it was known as Athura, the Achaemenid name for Assyria.[30][31]

The region fell to Alexander The Great in 332 BC and was thereafter ruled by the Greek Seleucid Empire until the middle of the second century BC (and was renamed Syria, a Greek corruption of Assyria), when it fell to Mithridates I of Parthia. The Assyrian semi-independent kingdom of Adiabene was centred in Erbil in the first Christian centuries.[32][33][34][35] Later, the region was incorporated by the Romans as the Roman Assyria province but shortly retaken by the Sassanids who established the Satrap of Assuristan (Sassanid Assyria) in it until the Arab Islamic conquest. The region became a center of the Assyrian Church of the East and a flourishing Syriac literary tradition during Sassanid rule.[36][37][38]

Islamic period

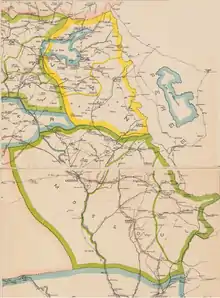

_(Mosul_vilayet).jpg.webp)

The region was conquered by Arab Muslims in the mid 7th century AD as the invading forces conquered the Sassanian Empire, while Assyria was dissolved as a geo-political entity (although Assyrians remain in the area to this day), and the area made part of the Muslim Arab Rashidun, Umayyad, and later the Abbasid Caliphates, before becoming part of various Iranian, Turkic, and Mongol emirates. Following the disintegration of the Ak Koyunlu, all of its territories including what is modern-day Iraqi Kurdistan passed to the Iranian Safavids in the earliest 16th century.

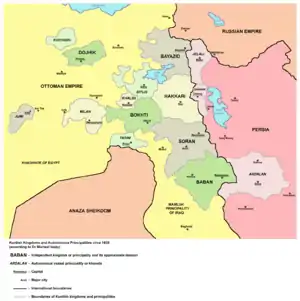

Between the 16th and 17th century the area nowadays known as Iraqi Kurdistan, (formerly ruled by three principalities of Baban, Badinan, and Soran) was continuously passed back and forth between archrivals the Safavids and the Ottomans, until the Ottomans managed to decisively seize power in the region starting from the mid 17th century through the Ottoman–Safavid War (1623–39) and the resulting Treaty of Zuhab.[39] In the early 18th century, it briefly passed to the Iranian Afsharids led by Nader Shah. Following Nader's death in 1747, Ottoman suzerainty was reimposed, and in 1831, direct Ottoman rule was established which lasted until World War I, when the Ottomans were defeated by the British.

Kurdish revolts under British control

During World War I, the British and French divided Western Asia in the Sykes-Picot Agreement. The Treaty of Sèvres (which did not enter into force), and the Treaty of Lausanne which superseded it, led to the advent of modern Western Asia and the modern Republic of Turkey. The League of Nations granted France mandates over Syria and Lebanon and granted the United Kingdom mandates over Palestine (which then consisted of two autonomous regions: Mandatory Palestine and Transjordan) and what was to become Iraq. Parts of the Ottoman Empire on the Arabian Peninsula were eventually taken over by Saudi Arabia and Yemen.

.png.webp)

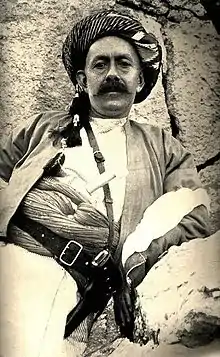

In 1922, Britain restored Shaikh Mahmud Barzanji to power, hoping that he would organize the Kurds to act as a buffer against the Turks, who had territorial claims over Mosul and Kirkuk. However, defiant to the British, in 1922 Shaikh Mahmud declared a Kurdish Kingdom with himself as king. It took two years for the British to bring Kurdish areas into submission, while Shaikh Mahmud found refuge in an unknown location.

In 1930, following the announcement of the admission of Iraq to the League of Nations, Shaikh Mahmud started a third uprising which was suppressed with British air and ground forces.[40][41]

By 1927, the Barzani clan had become vocal supporters of Kurdish rights in Iraq. In 1929, the Barzani demanded the formation of a Kurdish province in northern Iraq. Emboldened by these demands, in 1931 Kurdish notables petitioned the League of Nations to set up an independent Kurdish government. In late 1931, Ahmed Barzani initiated a Kurdish rebellion against Iraq, and though defeated within several months, the movement gained a major importance in the Kurdish struggle later on, creating the ground for such a notable Kurdish rebel as Mustafa Barzani.

During World War II, the power vacuum in Iraq was exploited by the Kurdish tribes and under the leadership of Mustafa Barzani a rebellion broke out in the north, effectively gaining control of Kurdish areas until 1945, when Iraqis could once again subdue the Kurds with British support. Under pressure from the Iraqi government and the British, the most influential leader of the clan, Mustafa Barzani was forced into exile in Iran in 1945. Later he moved to the Soviet Union after the collapse of the Republic of Mahabad in 1946.[42][43]

Barzani Revolt (1960–1970)

After the military coup by Abdul Karim Qasim in 1958, Mustafa Barzani was invited by Qasim to return from exile, where he was greeted with a hero's welcome. As part of the deal arranged between Qasim and Barzani, Qasim had promised to give the Kurds regional autonomy in return for Barzani's support for his policies. Meanwhile, during 1959–1960, Barzani became the head of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), which was granted legal status in 1960. By early 1960, it became apparent that Qasim would not follow through with his promise of regional autonomy. As a result, the KDP began to agitate for regional autonomy. In the face of growing Kurdish dissent, as well as Barzani's personal power, Qasim began to incite the Barzanis historical enemies, the Baradost and Zebari tribes, which led to intertribal warfare throughout 1960 and early 1961.

By February 1961, Barzani had successfully defeated the pro-government forces and consolidated his position as leader of the Kurds. At this point, Barzani ordered his forces to occupy and expel government officials from all Kurdish territory. This was not received well in Baghdad, and as a result, Qasim began to prepare for a military offensive against the north to return government control of the region. Meanwhile, in June 1961, the KDP issued a detailed ultimatum to Qasim outlining Kurdish grievances and demanded rectification. Qasim ignored the Kurdish demands and continued his planning for war.

It was not until September 10, when an Iraqi army column was ambushed by a group of Kurds, that the Kurdish revolt truly began. In response to the attack, Qasim lashed out and ordered the Iraqi Air Force to indiscriminately bomb Kurdish villages, which ultimately served to rally the entire Kurdish population to Barzani's standard. Due to Qasim's profound distrust of the Iraqi Army, which he purposely failed to adequately arm (in fact, Qasim implemented a policy of ammunition rationing), Qasim's government was not able to subdue the insurrection. This stalemate irritated powerful factions within the military and is said to be one of the main reasons behind the Ba'athist coup against Qasim in February 1963. In November 1963, after considerable infighting amongst the civilian and military wings of the Ba'athists, they were ousted by Abdul Salam Arif in a coup. Then, after another failed offensive, Arif declared a ceasefire in February 1964 which provoked a split among Kurdish urban radicals on one hand and Peshmerga (Freedom fighters) forces led by Barzani on the other.

Barzani agreed to the ceasefire and fired the radicals from the party. Following the unexpected death of Arif, whereupon he was replaced by his brother, Abdul Rahman Arif, the Iraqi government launched a last-ditch effort to defeat the Kurds. This campaign failed in May 1966, when Barzani forces thoroughly defeated the Iraqi Army at the Battle of Mount Handrin, near Rawandiz. At this battle, it was said that the Kurds slaughtered an entire brigade.[44][45] Recognizing the futility of continuing this campaign, Rahamn Arif announced a 12-point peace program in June 1966, which was not implemented due to the overthrow of Rahman Arif in a 1968 coup by the Baath Party.

The Ba'ath government started a campaign to end the Kurdish insurrection, which stalled in 1969. This can be partly attributed to the internal power struggle in Baghdad and also tensions with Iran. Moreover, the Soviet Union pressured the Iraqis to come to terms with Barzani. A peace plan was announced in March 1970 and provided for broader Kurdish autonomy. The plan also gave Kurds representation in government bodies, to be implemented in four years.[46] Despite this, the Iraqi government embarked on an Arabization program in the oil rich regions of Kirkuk and Khanaqin in the same period.[47]

In the following years, Baghdad government overcame its internal divisions and concluded a treaty of friendship with the Soviet Union in April 1972 and ended its isolation within the Arab world. On the other hand, Kurds remained dependent on the Iranian military support and could do little to strengthen their forces.

Autonomy negotiations (1970–1974)

Regional autonomy had originally been established in 1970 with the creation of the Kurdish Autonomous Region following the agreement of an Autonomy Accord between the government of Iraq and leaders of the Iraqi Kurdish community. A Legislative Assembly was established and Erbil became the capital of the new entity which lay in Northern Iraq, encompassing the Kurdish authorities of Erbil, Dahuk and Sulaymaniyah. The one-party rule which had dominated Iraq however meant that the new assembly was an overall component of Baghdad's central government; the Kurdish authority was installed by Baghdad and no multi-party system had been inaugurated in Iraqi Kurdistan, and as such the local population enjoyed no particular democratic freedom denied to the rest of the country.

Second Kurdish Iraqi War Algiers Agreement

In 1973, the US made a secret agreement with the Shah of Iran to begin covertly funding Kurdish rebels against Baghdad through the Central Intelligence Agency and in collaboration with the Mossad, both of which would be active in the country through the launch of the Iraqi invasion and into the present.[48] By 1974, the Iraqi government retaliated with a new offensive against the Kurds and pushed them close to the border with Iran. Iraq informed Tehran that it was willing to satisfy other Iranian demands in return for an end to its aid to the Kurds. With mediation by Algerian President Houari Boumediene, Iran and Iraq reached a comprehensive settlement in March 1975 known as the Algiers Pact.[49] The agreement left the Kurds helpless and Tehran cut supplies to the Kurdish movement. Barzani went to Iran with many of his supporters. Others surrendered en masse and the rebellion ended after a few days.

As a result, the Iraqi government extended its control over the northern region after 15 years and in order to secure its influence, started an Arabization program by moving Arabs to the vicinity of oil fields in northern Iraq, particularly those around Kirkuk, and other regions, which were populated by Kurds.[50] The repressive measures carried out by the government against the Kurds after the Algiers agreement led to renewed clashes between the Iraqi Army and Kurdish guerrillas in 1977. In 1978 and 1979, 600 Kurdish villages were burned down and around 200,000 Kurds were deported to the other parts of the country.[51]

Arabization campaign and PUK insurgency

The Ba'athist government of Iraq forcibly displaced and culturally Arabized minorities (Kurds, Yezidis, Assyrians, Shabaks, Armenians, Turkmen, Mandeans), in line with settler colonialist policies, from the 1960s to the early 2000s, in order to shift the demographics of North Iraq towards Arab domination. The Baath party under Saddam Hussein engaged in active expulsion of minorities from the mid-1970s onwards.[52] In 1978 and 1979, 600 Kurdish villages were burned down and around 200,000 Kurds were deported to the other parts of the country.[51]

The campaigns took place during the Iraqi–Kurdish conflict, being largely motivated by the Kurdish–Arab ethnic and political conflict. Arab settlement programs reached their peak during the late 1970s, in line with depopulation efforts of the Ba'athist regime. The Baathist policies motivating those events are sometimes referred to as "internal colonialism",[53] described by Dr. Francis Kofi Abiew as a "Colonial 'Arabization'" program, including large-scale Kurdish deportations and forced Arab settlement in the region.[54]

Iran–Iraq War and Anfal Campaign

During the Iran–Iraq War, the Iraqi government again implemented anti-Kurdish policies and a de facto civil war broke out. Iraq was widely condemned by the international community, but was never seriously punished for oppressive measures, including the use of chemical weapons against the Kurds,[55] which resulted in thousands of deaths. The Al-Anfal Campaign constituted a systematic genocide of the Kurdish people in Iraq. The first wave of the plan was carried out in 1982 when 8,000 Barzanis were arrested and their remains were returned to Kurdistan in 2008.

The second and more extensive and widespread wave began from March 29, 1987 until April 23, 1989, when the Iraqi army under the command of Saddam Hussein & Ali Hassan al-Majid carried out a genocidal campaign against the Kurds, characterized by the following human rights violations: The widespread use of chemical weapons, the wholesale destruction of some 2,000 villages, and slaughter of around 50,000 rural Kurds, by the most conservative estimates. The large Kurdish town of Qala Dizeh (population 70,000) was completely destroyed by the Iraqi army. The campaign also included Arabization of Kirkuk, a program to drive Kurds and other ethnic groups out of the oil-rich city and replace them with Arab settlers from central and southern Iraq.[56]

After the Persian Gulf War

Even though autonomy had been agreed in 1970, local population enjoyed no particular democratic freedom denied to the rest of the country. Things began to change after the 1991 uprising against Saddam Hussein at the end of the Persian Gulf War. United Nations Security Council Resolution 688 gave birth to a safe haven following international concern for the safety of Kurdish refugees. The U.S. and the Coalition established a No Fly Zone over a large part of northern Iraq (see Operation Provide Comfort),[57] however, it left out Sulaymaniyah, Kirkuk and other important Kurdish populated regions. Bloody clashes between Iraqi forces and Kurdish troops continued and, after an uneasy and shaky balance of power was reached, the Iraqi government fully withdrew its military and other personnel from the region in October 1991 allowing Iraqi Kurdistan to function de facto independently. The region was to be ruled by the two principal Kurdish parties; the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). The region also has its own flag and national anthem.

At the same time, Iraq imposed an economic blockade over the region, reducing its oil and food supplies.[58] Elections held in June 1992 produced an inconclusive outcome, with the assembly divided almost equally between the two main parties and their allies. During this period, the Kurds were subjected to a double embargo: one imposed by the United Nations on Iraq and one imposed by Saddam Hussein on their region. The severe economic hardships caused by the embargoes fueled tensions between the two dominant political parties, the KDP and the PUK, over control of trade routes and resources.[59] Relations between the PUK and the KDP started to become dangerously strained from September 1993 after rounds of amalgamations occurred between parties.[60] This led to internecine and intra-Kurdish conflict and warfare between 1994 and 1996.

After 1996, 13% of the Iraqi oil sales were allocated for Iraqi Kurdistan and this led to relative prosperity in the region.[61] In return, the Kurds under KDP enabled Saddam to establish an oil smuggling route through territory controlled by the KDP, with the active involvement of senior Barzani family members. The taxation of this trade at the crossing point between Saddam's territory and Kurdish controlled territory and then into Turkey, along with associated service revenue, meant that whoever controlled Dohuk and Zakho had the potential to earn several million dollars a week.[62] Direct United States mediation led the two parties to a formal ceasefire in what was termed the Washington Agreement in September 1998. It is also argued that the Oil-for-Food Programme from 1997 onward had an important effect on cessation of hostilities.[63]

During and after US-led invasion

Iraqi Kurds played an important role in the Iraq War. Kurdish parties joined forces against the Iraqi government during the war in Spring 2003. Kurdish military forces, known as Peshmerga, played an important role in the overthrow of the Iraqi government;[64] however, Kurds have been reluctant to send troops into Baghdad since then, preferring not to be dragged into the sectarian struggle that so dominates much of Iraq.[65]

A new constitution of Iraq was established in 2005, defining Iraq as a federalist state consisting of Regions and Governorates. It recognized both the Kurdistan Region and all laws passed by the KRG since 1992. There is provision for Governorates to create, join or leave Regions. However, as of late 2015, no new Regions have been formed, and the KRG remains the only regional government within Iraq.

PUK leader Jalal Talabani was elected President of the new Iraqi administration, while KDP leader Masoud Barzani became President of the Kurdistan Regional Government.

Since the downfall of the regime of Saddam Hussein, the relations between the KRG and Turkey have been in flux. Tensions marked a high stage in late February 2008 when Turkey unilaterally took military action against the PKK which at times uses the northern Iraq region as a base for militant activities against Turkey. The incursion, which lasted eight days, could have drawn the armed forces of Kurdistan into a broader regional war. However, relations have been improved since then, and Turkey now has the largest share of foreign investment in Kurdistan.

Following US withdrawal

Tensions between Iraqi Kurdistan and the central Iraqi government mounted through 2011–2012 on the issues of power sharing, oil production and territorial control. In April 2012, the president of Iraq's semi-autonomous northern Kurdish region demanded that officials agree to their demands or face the prospect of secession from Baghdad by September 2012.[66]

In September 2012, the Iraqi government ordered the KRG to transfer its powers over the Peshmerga to the central government. Relations became further strained by the formation of a new command center (Tigris Operation Command) for Iraqi forces to operate in a disputed area over which both Baghdad and the Kurdistan Regional Government claim jurisdiction.[67] On 16 November 2012 a military clash between the Iraqi forces and the Peshmerga resulted in one person killed.[67] CNN reported that two people were killed (one of them an Iraqi soldier) and ten wounded in clashes at the Tuz Khurmato town.[68]

As of 2014, Iraqi Kurdistan is in dispute with the Federal Iraqi government on the issues of territorial control, export of oil and budget distribution and is functioning largely outside Baghdad's control. With the escalation of the Iraqi crisis and fears of Iraq's collapse, Kurds have increasingly debated the issue of independence. During the 2014 Northern Iraq offensive, Iraqi Kurdistan seized the city of Kirkuk and the surrounding area, as well as most of the disputed territories in Northern Iraq. On 1 July 2014, Masoud Barzani announced that "Iraq's Kurds will hold an independence referendum within months."[69] After previously opposing the independence for Iraqi Kurdistan, Turkey later gave signs that it could recognize an independent Kurdish state.[69][70] On 11 July 2014, KRG forces seized control of the Bai Hassan and Kirkuk oilfields, prompting a condemnation from Baghdad and a threat of "dire consequences" if the oilfields were not relinquished back to Iraq's control.[71]

In September, Kurdish leaders decided to postpone the referendum so as to focus on the fight against ISIL.[72] In November, Ed Royce, Chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the United States House of Representatives, introduced legislation to arm the Kurds directly, rather than continue working through the local governments.[73]

In August 2014, the US began a campaign of airstrikes in Iraq, in part to protect Kurdish areas such as Erbil from the militants.[74]

In February 2016, Kurdish president Barzani stated once again that "Now the time is ripe for the people of Kurdistan to decide their future through a referendum", supporting an independence referendum and citing similar referenda in Scotland, Catalonia and Quebec.[75] On March 23, Barzani officially declared that Iraqi Kurdistan will hold the referendum some time "before October" of that year.[76] On April 2, 2017, the two governing parties released a joint statement announcing they would form a joint committee to prepare for a referendum to be held on 25 September.[77]

The 2017 Kurdistan Region independence referendum took place on September 25, with 92.73% voting in favor of independence.[78] This triggered a military operation in which the Iraqi government retook control of Kirkuk and surrounding areas,[79] and forced the KRG to annul the referendum.[80]

Culture

Kurdish culture is a group of distinctive cultural traits practiced by Kurdish people. The Kurdish culture is a legacy from the various ancient peoples who shaped modern Kurds and their society, but primarily Iranian. Among their neighbours, the Kurdish culture is closest to Persian culture. For example, they celebrate Newroz as the new year day, which is celebrated on March 21. It is the first day of the month of Xakelêwe in Kurdish calendar and the first day of spring.[81] Other peoples such as Arabs, Assyrians, Armenians, Shabaks and Mandeans have their own distinctive cultures.

References

- Ali, Othman (October 1997). "Southern Kurdistan during the last phase of Ottoman control: 1839–1914". Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 17 (2): 283–291. doi:10.1080/13602009708716377.

- "مێژوو "وارماوا" له كوردستان" (in Kurdish). Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- "عێراقی دوای سەددام و چارەنووسی باشووری کوردستان" (in Kurdish). Lund University Publications. 2008.

- "Ala û sirûda netewiya Kurdistanê" (in Kurdish). Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- Bengio, Ofra (2014). Kurdish Awakening: Nation Building in a Fragmented Homeland. University of Texas Press. p. 2.

Hence the terms: rojhalat (east, Iran), bashur (south, Iraq), bakur (north, Turkey), and rojava (west, Syria).

- Khalil, Fadel (1992). Kurden heute (in German). Europaverlag. pp. 5, 18–19. ISBN 3-203-51097-9.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-28. Retrieved 2016-11-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- The Edinburgh encyclopaedia, conducted by D. Brewster—Page 511, Original from Oxford University—published 1830

- An Account of the State of Roman-Catholick Religion, Sir Richard Steele, Published 1715

- N. Maxoudian, "Early Armenia as an Empire: The Career of Tigranes III, 95–55 BC", Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society, Vol. 39, Issue 2, April 1952, pp. 156–163.

- A.D. Lee, The Role of Hostages in Roman Diplomacy with Sasanian Persia, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, Vol. 40, No. 3 (1991), pp. 366–374 (see p.371)

- Village on the Euphrates: From Foraging to Farming at Abu Hureyra, by A.M.T Moore, G.C. Hillman and A.J Legge, Published 2000, Oxford University Press

- A Dictionary of Scripture Geography, p 57, by John Miles, 486 pages, Published 1846, Original from Harvard University

- Al-Sheikhly, O.F.; and Nader, I.A. (2013). The Status of the Iraq Smooth-coated Otter Lutrogale perspicillata maxwelli Hayman 1956 and Eurasian Otter Lutra lutra Linnaeus 1758 in Iraq. Archived 2017-08-07 at the Wayback Machine IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 30(1).

- C.Michael Hogan. 2009. Hooded Crow: Corvus cornix. GlobalTwitcher. Archived 2010-11-26 at the Wayback Machine ed. N.Stromberg

- "Iraq's Marshes Show Progress toward Recovery". Wildlife Extra. Archived from the original on 9 May 2010. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- "Shaqlawa". Ishtar Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 2016-08-27. Retrieved 2017-01-21.

- "Climate: Arbil – Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- "Irbil, Iraq Climate". My Forecast. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- "Erbil climate info". What's the Weather Like.org. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- "Erbil Weather Forecast and Climate Information". Erbilia. Archived from the original on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- "Climate statistics for Barzan". Climate Data. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- "Climate statistics for Batufa". Climate-Data. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- "Weather averages for Amadiya". World Weather Online. Archived from the original on September 6, 2014. Retrieved September 6, 2014.

- "Weather averages for Amadiya". Climate-Data. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- Malati J. Shendge (1 January 1997). The language of the Harappans: from Akkadian to Sanskrit. Abhinav Publications. p. 46. ISBN 978-81-7017-325-0. Archived from the original on 20 June 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- Bertman, Stephen (2003). Handbook to life in ancient Mesopotamia. Infobase Publishing. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-8160-4346-0. Archived from the original on 2016-01-07. Retrieved 2015-10-12.

- Barton, George Aaron (1902). A sketch of Semitic origins: social and religious. The Macmillan Company. p. 262.

ishtar shrine arbela.

- J. F. Hansman, ARBELA Archived 2011-12-30 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopedia Iranica.

- Curtis, John (November 2003). "The Achaemenid Period in Northern Iraq" (PDF). L'Archéologie de l'Empire Achéménide. Paris, France: 3–4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-06-13. Retrieved 2011-06-20.

- Dandamatev, Muhammad:"Assyria. ii- Achaemenid Aθurā". Archived from the original on 2008-05-29. Retrieved 2008-04-12., Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- "The Chronicle of Arbela" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-04-28. Retrieved 2011-06-20.

In 115, the Romans invaded Adiabene and re named it Assyria.

- The Biblical Geography of Central Asia: with a General Introduction, by Ernst Friedrich Carl Rosenmüller. Page 122.

- Neusner, Jacob (1962). "In Memory of Rabbi and Mrs. Carl Friedman: Studies on the Problem of Tannaim in Babylonia (ca. 130–160 C.E.)". Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research. 30: 79–127. doi:10.2307/3622535. JSTOR 3622535.

- Ammianus Marcellinus, another fourth-century writer. In his excursus on the Sasanian Empire, he describes Assyria in such a way that there is no mistaking he is talking about lower Mesopotamia (Amm. Marc. XXIII. 6. 15). For Assyria, he lists three major cities – Babylon, Ctesiphon and Seleucia (Amm. Marc. xxIII. 6. 23) – whereas he refers to Adiabene as Assyria priscis temporibus vocitata (Amm. Marc. xxIII. 6. 20).

- K. Schippmann, ASSYRIA Archived 2011-12-30 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopedia Iranica

- Lightfoot, C. S. (1990). "Trajan's Parthian War and the Fourth-Century Perspective". Journal of Roman Studies. 80: 115–126. doi:10.2307/300283. JSTOR 300283.

- Lightfoot p. 121; Magie p. 608.

- Roemer (1989), p. 285

- Dahlman, C. (2002). "The Political Geography of Kurdistan". Eurasian Geography and Economics. 43 (4): 271–299 [p. 286]. doi:10.2747/1538-7216.43.4.271. S2CID 146638619.

- Eskander, Saad (2000). "Britain's Policy in Southern Kurdistan: The Formation and Termination of the First Kurdish Government, 1918-1919". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 27 (2): 139–163 [pp. 151, 152, 155, 160]. doi:10.1080/13530190020000501. S2CID 144862193.

- Harris, G. S. (1977). "Ethnic Conflict and the Kurds". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 433 (1): 112–124 [p. 118]. doi:10.1177/000271627743300111. S2CID 145235862.

- Saedi, Michael J. Kelly; foreword by Ra'id Juhi al (2008). Ghosts of Halabja : Saddam Hussein and the Kurdish genocide. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Security International. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-275-99210-1. Archived from the original on 2016-01-07. Retrieved 2015-10-12.

- O'Ballance, Edgar (1973). The Kurdish Revolt, 1961–1970. Hamden: Archon Books. ISBN 0208013954.

- Pollack, Kenneth M. (2002). Arabs at War. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803237332.

- Harris, G. S. (1977). "Ethnic Conflict and the Kurds". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 433 (1): 112–124 [pp. 118–120]. doi:10.1177/000271627743300111. S2CID 145235862.

- "Introduction : GENOCIDE IN IRAQ: The Anfal Campaign Against the Kurds (Human Rights Watch Report, 1993)". Hrw.org. Archived from the original on 2010-06-15. Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- "A Chronology of U.S.-Kurdish History" Archived 2017-10-10 at the Wayback Machine, PBS. Retrieved 20 Aug 2011.

- "Page 9 – The Internally Displaced People of Iraq" (PDF). The Brookings Institution–SAIS Project. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- Harris, G. S. (1977). "Ethnic Conflict and the Kurds". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 433 (1): 112–124 [p. 121]. doi:10.1177/000271627743300111. S2CID 145235862.

- Farouk-Sluglett, M.; Sluglett, P.; Stork, J. (July–September 1984). "Not Quite Armageddon: Impact of the War on Iraq". MERIP Reports: 24.

- Eva Savelsberg, Siamend Hajo, Irene Dulz. Effectively Urbanized – Yezidis in the Collective Towns of Sheikhan and Sinjar. Etudes rurales 2010/2 (n°186). ISBN 9782713222955

- Prof. Rimki Basu. International Politics: Concepts, Theories and Issues:p103. 2012.

- Francis Kofi Abiew. The Evolution of the Doctrine and Practice of Humanitarian Intervention:p146. 1991.

- "Death Clouds: Saddam Hussein's Chemical War Against the Kurds". Dlawer.net. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- "Human Rights Watch Report About Anfal Campaign, 1993". Hrw.org. Archived from the original on 2010-10-19. Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- Fawcett, L. (2001). "Down but not out? The Kurds in International Politics". Review of International Studies. 27 (1): 109–118 [p. 117]. doi:10.1017/S0260210500011098.

- Leezenberg, M. (2005). "Iraqi Kurdistan: contours of a post-civil war society" (PDF). Third World Quarterly. 26 (4–5): 631–647 [p. 636]. doi:10.1080/01436590500127867. S2CID 154579710.

- Barkey, H. J.; Laipson, E. (2005). "Iraqi Kurds And Iraq's Future". Middle East Policy. 12 (4): 66–76 [p. 67]. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4967.2005.00225.x.

- Stansfield, G. R. V. (2003). Iraqi Kurdistan: Political Development and Emergent Democracy. New York: Routledge. p. 96. ISBN 0415302781.

- Gunter, M. M.; Yavuz, M. H. (2005). "The continuing Crisis In Iraqi Kurdistan". Middle East Policy. 12 (1): 122–133 [pp. 123–124]. doi:10.1111/j.1061-1924.2005.00190.x.

- Stansfield, G.; Anderson, L. (2004). The Future of Iraq: Dictatorship, Democracy, or Division?. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 174. ISBN 1403963541.

- Leezenberg, M. (2005). "Iraqi Kurdistan: contours of a post-civil war society" (PDF). Third World Quarterly. 26 (4–5): 631–647 [p. 639]. doi:10.1080/01436590500127867. S2CID 154579710.

- "Title page for ETD etd-11142005-144616". Etd.lib.fsu.edu. 2005-10-28. Archived from the original on 2010-08-20. Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- Abdulrahman, Frman. "Kurds Reluctant to Send Troops to Baghdad". IWPR Institute for War & Peace Reporting. Archived from the original on 2010-08-20. Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-05-08. Retrieved 2013-06-23.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Iraqi Kurdish leader says region will defend itself". Reuters. 2012-11-18. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2017-07-01.

- "Two dead, 10 wounded after Iraqi, Kurdish forces clash in northern Iraq – CNN.com". CNN. 2012-11-19. Archived from the original on 2012-11-22. Retrieved 2013-06-23.

- Agence France Presse (1 July 2014). "Kurdish Leader: We Will Vote For Independence Soon". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- "The tide is finally turning for the Kurds – Especially in Turkey". Business Insider. 3 July 2014. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "Tensions mount between Baghdad and Kurdish region as Kurds seize oil fields". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- Gutman, Roy (2014-09-05). "Kurdish leaders are postponing plans for a referendum on independence and say they instead will devote their efforts to forging a new Iraqi government". The Toronto Star. ISSN 0319-0781. Archived from the original on 2016-03-17. Retrieved 2016-03-30.

- McLEARY, PAUL (20 November 2014). "House Republican Wants To Work Around Baghdad, Arm the Kurds". www.defensenews.com. Gannett. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- Arun, Neil (1970-01-01). "BBC News – Iraq conflict: Why Irbil matters". Bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2014-08-09. Retrieved 2014-08-09.

- By Rudaw. "Barzani: Time is ripe for referendum; Kurdish independence brings the region peace". Rudaw. Archived from the original on 2018-10-29. Retrieved 2018-10-29.

- "Barzani: Kurdistan will hold referendum before October". Kudistan24. March 23, 2016. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- "Kurdistan will hold independence referendum in 2017, senior official". Archived from the original on 2017-04-02. Retrieved 2017-04-02.

- "Massive 'yes' vote in Iraqi Kurd independence referendum". Rappler. 27 September 2017. Retrieved 2020-08-11.

- "Iraqi forces seize oil city Kirkuk from Kurds in bold advance". Reuters. 17 October 2017. Retrieved 2017-08-11.

- "Iraq's Kurdistan says to respect court decision banning secession". Reuters. 14 November 2017. Retrieved 2020-08-11.

- "Cultural Orientation Resource Center". Archived from the original on 2001-04-19. Retrieved 2008-10-22.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Iraqi Kurdistan. |

- Travel Iraqi Kurdistan – Travel Information and forum for the region.

- The Kurdish Institute of Paris – Provides news, bulletins, articles and conference information on the situation in Iraqi Kurdistan.

- Iraqi Kurdistan timeline

- Kurdistan’s Politicized Society Confronts a Sultanistic System (Carnegie Paper)

- The Kurds of Iraq

- Kurdistan – The Other Iraq at the Wayback Machine (archived 2012-02-13)

- Baghdad Invest at the Library of Congress Web Archives (archived 2015-11-15) – Kurdistan Investment Research

- GoKurdistan.com – Detailed travel guide to Iraqi Kurdistan

- Iraq Visas at the Wayback Machine (archived 2012-01-20) – Information and photos regarding Iraqi Kurdistan visas issued by the Kurdistan Regional Government (as opposed to federal Iraqi government)

- Kurds in the Contemporary Middle East

.jpg.webp)