Greater Albania

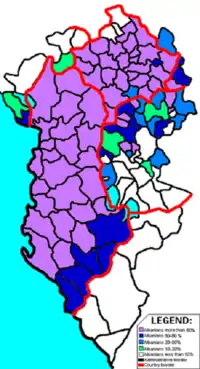

Greater Albania is an irredentist[1] and nationalist concept that seeks to unify the lands that many Albanians consider to form their national homeland[2] It is based on claims on the present-day or historical presence of Albanian populations in those areas. In addition to the existing Albania, the term incorporates claims to regions in the neighbouring states, the areas include Kosovo,[a] the Preševo Valley of Serbia, territories in southern Montenegro, northwestern Greece (the Greek regional units of Thesprotia and Preveza, referred by Albanians as Chameria, and other territories that were part of the Vilayet of Yanina during the Ottoman Empire),[3][4][5][6][7] and a western part of North Macedonia.

The unification of an even larger area into a single territory under Albanian authority had been theoretically conceived by the League of Prizren, an organization of the 19th century whose goal was to unify the Albanian inhabited lands (and other regions, mostly from the region of Macedonia, Epirus and Montenegro) into a single autonomous Albanian Vilayet within the Ottoman Empire.[8] However, the concept of a Greater Albania, as in greater than Albania within its 1913 borders, was implemented only under the Italian and Nazi German occupation of the Balkans during World War II.[9] The idea of unification, has roots in the events of the Treaty of London in 1913, when roughly half of the predominantly Albanian territories and 40% of the population were left outside the new country's borders.[10]

Terminology

Greater Albania is a term used mainly by the Western scholars, politicians, etc. Albanian nationalists dislike the expression "Greater Albania" and prefer to use the term "Ethnic Albania".[11] Ethnic Albania (Albanian: Shqipëria Etnike) is a term used primarily by Albanian nationalists to denote the territories claimed as the traditional homeland of ethnic Albanians, despite these lands also being inhabited by many non-Albanians.[12] Those that use the second term refer to an area which is smaller than the four Ottoman vilayets, while still encompassing Albania, Kosovo, western North Macedonia, Albanian populated areas of Southern Serbia and parts of Northern Greece (Chameria) that had a historic native Albanian population.[11] Albanian nationalists ignore that within these regions there are also sizable numbers of non-Albanians.[11] Another term used by Albanians, is "Albanian national reunification" (Albanian: Ribashkimi kombëtar shqiptar).[13]

History

Under the Ottoman Empire

Prior to the Balkan wars of the beginning of the 20th century, Albanians were subjects of the Ottoman Empire. The Albanian independence movement emerged in 1878 with the League of Prizren (a council based in Kosovo) whose goal was cultural and political autonomy for ethnic Albanians inside the framework of the Ottoman Empire. However, the Ottomans were not prepared to grant The League's demands. Ottoman opposition to the League's cultural goals eventually helped transform it into an Albanian national movement.

Albanian nationalism overall was a reaction to the gradual breakup of the Ottoman Empire and a response to Balkan and Christian national movements that posed a threat to an Albanian population that was mainly Muslim.[14] Efforts were devoted to including vilayets with an Albanian population into a larger unitary Albanian autonomous province within the Ottoman state while Greater Albania was not considered a priority.[14][15][16] Albanian nationalism during the late Ottoman era was not imbued with separatism that aimed to create an Albanian nation-state, though Albanian nationalists did envisage an independent Greater Albania.[6][14][17] Albanian nationalists were mainly focused on defending rights that were sociocultural, historic and linguistic within existing countries without being connected to a particular polity.[14][15]

Balkan Wars and Albanian Independence (1912–1913)

The imminence of collapsing Ottoman rule through military defeat during the Balkan wars pushed Albanians represented by Ismail Qemali to declare independence (28 November 1912) in Vlorë from the Ottoman Empire.[18] The main motivation for independence was to prevent Balkan Albanian inhabited lands from being annexed by Greece and Serbia.[18][19] Italy and Austria-Hungary supported Albanian independence due to their concerns that Serbia with an Albanian coast would be a rival power in the Adriatic Sea and open to influence from its ally Russia.[20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27] Apart from geopolitical interests, some Great powers were reluctant to include more Ottoman Balkan Albanian inhabited lands into Albania due to concerns that it would be the only Muslim dominated state in Europe.[28] Russo-French proposals were for a truncated Albania based on central Albania with a mainly Muslim population, which was also supported by Serbia and Greece who considered that only Muslims could only be Albanians.[29] As more Albanians became part of the Serbian and Greek states, Albanian scholars with nationalistic perspectives interpret the declaration of independence as a partial victory for the Albanian nationalist movement.[30]

World War II

On 7 April 1939, Italy headed by Benito Mussolini after prolonged interest and overarching sphere of influence during the interwar period invaded Albania.[31] Italian fascist regime members such as Count Galeazzo Ciano pursued Albanian irredentism with the view that it would earn Italians support among Albanians while also coinciding with Italian war aims of Balkan conquest.[32] The Italian annexation of Kosovo to Albania was considered a popular action by Albanians of both areas.[33] Western Macedonia was also annexed by Italy to their protectorate of Albania.[34][35] In newly acquired territories, non-Albanians had to attend Albanian schools that taught a curriculum containing nationalism alongside fascism and were made to adopt Albanian forms for their names and surnames.[36] Members from the landowning elite, liberal nationalists opposed to communism with other sectors of society in Albania came to form the Balli Kombëtar organisation and the collaborationist government under the Italians which all as nationalists sought to preserve Greater Albania.[37][38][36]

Many Kosovo Albanians were preoccupied with driving out the Serb community, particularly the post-1919 Serbian and Montenegrin colonists,[39] often settled on confiscated Albanian property.[40] Albanians saw Serbian and Yugoslav rule as foreign,[40] and according to Ramet they felt that anything would be better than the chauvinism, corruption, administrative hegemonism and exploitation they had experienced under the Serbian authorities.[41] Albanians collaborated broadly with the Axis occupiers, who had promised them a Greater Albania.[40] Collapse of Yugoslav rule resulted in actions of revenge being undertaken by Albanians, some joining the local Vulnetari militia that burned Serbian settlements and killed Serbs while interwar Serbian and Montenegrin colonists were expelled into Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia.[42][43][35] The aim of these actions were to create a homogeneous Greater Albanian state.[43] Italian authorities in Kosovo allowed the use of the Albanian language in schools, university education and administration.[44] The same nationalist sentiments among Albanians which welcomed the addition of Kosovo and its Albanians within an enlarged state also worked against the Italians as foreign occupation became increasingly rejected in Albania.[45] An attempt to get Kosovan Albanians to join the resistance, a meeting in Bujan (1943–1944), northern Albania was convened between Balli Kombëtar members and Albanian communists that agreed to common struggle and maintenance of the newly expanded boundaries.[46] The deal was opposed by Yugoslav partisans and later rescinded resulting in limited Kosovan Albanian recruits.[46] Some Balli Kombëtar members such as Shaban Polluzha became partisans with the view that Kosovo would become part of Albania.[47] With the end of the war, some of those Kosovan Albanians felt betrayed by the return of Yugoslav rule and for several years Albanian nationalists in Kosovo resisted both the partisans and later the new Yugoslav army.[48][47][49] Albanian nationalists viewed their inclusion within Yugoslavia as an occupation.[50]

The Albanian Fascist Party became the ruling party of the Italian Protectorate of Albania in 1939 and the prime minister Shefqet Verlaci approved the possible administrative union of Albania and Italy, because he wanted the Italian support in order to get the union of Kosovo, Chameria and other "Albanian irredentism" into Greater Albania. Indeed, this unification was realized after the Axis occupation of Yugoslavia and Greece from spring 1941. The Albanian fascists claimed in May 1941 that nearly all the Albanian populated territories were united to Albania.[9][51]

Between May 1941 and September 1943, Benito Mussolini placed nearly all the land inhabited by ethnic Albanians under the jurisdiction of an Albanian quisling government. That included the region of Kosovo, parts of Vardar Macedonia and some small border areas of Montenegro. In western Greek Epirus (designated by Albanians as Chameria) an Albanian high commissioner, Xhemil Dino, was appointed by the Italians; but the area remained under the control of the Italian military command in Athens and so technically remained a region of Greece.

When the Germans occupied the area and substituted the Italians, they maintained the borders created by Mussolini, but after World War II the Albanian borders were returned by the Allies to the pre-war status.

Yugoslav Wars

The Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) was an ethnic-Albanian paramilitary organisation which sought the separation of Kosovo from Yugoslavia during the 1990s and the eventual creation of a Greater Albania, encompassing Kosovo, Albania, and the ethnic Albanian minority of neighbouring Macedonia. The KLA found great moral and financial support among the Albanian diaspora.[52][53][54][55][56]

KLA Commander Sylejman Selimi insisted:[57]

There is de facto Albanian nation. The tragedy is that European powers after World War I decided to divide that nation between several Balkan states. We are now fighting to unify the nation, to liberate all Albanians, including those in Macedonia, Montenegro, and other parts of Serbia. We are not just a liberation army for Kosovo.

By 1998 the KLA's operations had evolved into a significant armed insurrection. According to the report of the USCRI, the "Kosovo Liberation Army ... attacks aimed at trying to 'cleanse' Kosovo of its ethnic Serb population." The UNHCR estimated the figure at 55,000 refugees who had fled to Montenegro and Central Serbia, most of whom were Kosovo Serbs.[58]

Its campaign against Yugoslav security forces, police, government officers and ethnic Serb villages precipitated a major Yugoslav military crackdown which led to the Kosovo War of 1998–1999. Military intervention by Yugoslav security forces led by Slobodan Milošević and Serb paramilitaries within Kosovo prompted an exodus of Kosovar Albanians and a refugee crisis that eventually caused NATO to intervene militarily in order to stop what was widely identified as an ongoing campaign of ethnic cleansing.[59][60]

The war ended with the Kumanovo Treaty, with Yugoslav forces agreeing to withdraw from Kosovo to make way for an international presence.[61][62] The Kosovo Liberation Army disbanded soon after this, with some of its members going on to fight for the UÇPMB in the Preševo Valley[63] and others joining the National Liberation Army (NLA) and Albanian National Army (ANA) during the armed ethnic conflict in Macedonia.[64]

2000s–present

Political parties advocating and willing to fight for a Greater Albania emerged in Albania during the 2000s.[65] They were the National Liberation Front of Albanians (KKCMTSH) and Party of National Unity (PUK) that both merged in 2002 to form the United National Albanian Front (FBKSh) which acted as the political organisation for the Albanian National Army (AKSh) militant group and consisted of some disaffected KLA and NLA members.[66][65] Regarded internationally as terrorist both have gone underground and its members have been involved in various violent incidents in Kosovo, Serbia and Macedonia during the 2000s.[66][67][68] In the early 2000s, the Liberation Army of Chameria (UCC) was a reported paramilitary formation that intended to be active in northern Greek region of Epirus.[69][70] Political parties active only in the political scene exist that have a nationalist outlook are the monarchist Legality Movement Party (PLL), the National Unity Party (PBKSh) alongside the Balli Kombëtar, a party to have passed the electoral threshold and enter parliament.[65][71] These political parties, some of whom advocate for a Greater Albania have been mainly insignificant and remained at the margins of the Albanian political scene.[71] The Kosovo question has limited appeal among Albanian voters who generally speaking are not interested in electing parties advocating redrawn borders creating a Greater Albania.[65] Centenary Albanian independence celebrations in 2012 generated nationalistic commentary among the political elite of whom prime-minister Sali Berisha referred to Albanian lands as extending to Preveza, northern Greece and Preševo, southern Serbia angering Albania's neighbors.[72] In Kosovo, a prominent left wing nationalist movement turned political party Vetëvendosje (Self Determination) has emerged who advocates for closer Kosovo-Albania relations and pan-Albanian self determination in the Balkans.[73][74] Another smaller nationalist party, the Balli Kombetar Kosovë (BKK) sees itself as an heir to the original Second World War organisation that supports Kosovan independence and pan-Albanian unification.[65] Greater Albania remains mainly in the sphere of political rhetoric and overall Balkan Albanians view EU integration as the solution to combat crime, weak governance, civil society and bringing different Albanian populations together.[75][71]

On 19 July 2020, singer of Albanian descent Dua Lipa faced backlash after she shared an image of a banner associated with supporters of extreme Albanian nationalism.[76] The same banner had sparked controversy at the 2014 Serbia vs. Albania football game.[77] The banner depicts the irredentist map of Greater Albania, while the caption, "autochthonous", alludes to the Illyrian theory of the origin of the Albanians. In response, Twitter users, many of them Macedonian, Greek, Montenegrin and Serbian, accused the singer of ethno-nationalism.[78][79] Political scientist Florian Bieber described Lipa's tweet as "stupid nationalism", an idea which claims that one group has greater rights because it was there earlier and that migrants to the nation should be deemed less worthy.[78]

Public opinion

According to the Gallup Balkan Monitor 2010 report, the idea of a Greater Albania was supported by the majority of Albanians in Albania (63%), Kosovo (81%) and the Republic of Macedonia (53%), although the same report noted that most Albanians thought this unlikely to happen.[80][81]

In a survey carried out by United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), published in March 2007, only 2.5% of the Albanians in Kosovo thought unification with Albania is the best solution for Kosovo. Ninety-six percent said they wanted Kosovo to become independent within its present borders.[82]

Political uses of the concept

The Albanian question in the Balkan peninsula is in part the consequence of the decisions made by Western powers in late 19th and early 20th century. The Treaty of San Stefano and the 1878 Treaty of Berlin assigned Albanian inhabited territories to other States, hence the reaction of the League of Prizren.[83] One theory posits that the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Austro-Hungary wanted to maintain a brittle balance in Europe in the late 19th century.

The degree to which different groups are working towards and what efforts such groups are undertaking in order to achieve a Greater Albania is disputed. There seems no evidence that anything more than a few unrepresentative extremist groups are working towards this cause; the vast majority of Albanians want to live in peace with their neighbors. However, they also want the human rights of the Albanian ethnic populations in North Macedonia, Serbia, Greece to be respected. An excellent example is the friendly relationship between the Montenegro and the support towards the integration of the Albanian population in North Macedonia. There is Albanian representation in government, the national parliament, local government, and the business sector, and no evidence of systematic discrimination on an ethnic or religious basis against the Albanian (or indeed any other minority) population.

In 2000, the then-US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright said that the international community would not tolerate any efforts towards the creation of a Greater Albania.[84]

In 2004, the Vetëvendosje movement was formed in Kosovo, which opposes foreign involvement in Kosovan affairs and campaigns instead for the sovereignty the people, as part of the right of self-determination. Vetëvendosje obtained 12.66% of the votes in an election in December 2010, and the party manifesto calls for a referendum on union with Albania.[85]

In 2012, the Red and Black Alliance (Albanian: Aleanca Kuq e Zi) was established as a political party in Albania, the core of its program is national unification of all Albanians in their native lands.[86]

In 2012, as part of the celebrations for 100th Anniversary of the Independence of Albania, Prime Minister Sali Berisha spoke of "Albanian lands" stretching from Preveza in Greece to Presevo in Serbia, and from the Macedonian capital of Skopje to the Montenegrin capital of Podgorica, angering Albania's neighbors. The comments were also inscribed on a parchment that will be displayed at a museum in the city of Vlore, where the country's independence from the Ottoman Empire was declared in 1912.[87]

Use in other media

The concept is also often used, especially with Ilirida (the proposed western region of North Macedonia), by nationalists in circles of Macedonian and Serbian politics in bids to rally support.[88]

Areas

| State/region/community | Territory | Area (km2) | Total population | Albanians |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albania (Albanian proper) |

28,748 | 2,821,977[89] | 2,312,356 (82% of total state pop.) | |

| Kosovo (Kosovo Albanians) |

10,908 | 1,739,825 (2011 census) |

1,616,869 (93% of total state pop.) | |

| Malësia, Kraja, Rožaje, Plav and Gusinje (Albanian community in Montenegro) |

1,173–1,400 | N/A | 25,000 | |

| Western North Macedonia (Albanian community in North Macedonia) |

2,500–4,500 | N/A | 509,083 (2002 census) | |

| Preševo Valley (Albanian community in central Serbia) |

725–1,249 | 88,966 (2002 census data) |

57,595 (65% of Preševo Valley) | |

| Epirus/Chameria (Cham Albanians) |

N/A | N/A | N/A |

Kosovo

Kosovo has an overwhelmingly Albanian majority, estimated to be around 88%.[90] The 2011 census stated a higher percentage Albanian people, but due to the exclusion of northern Kosovo, a Serb-dominated area, and a partial boycott by the Romani and Serb population in south Kosovo, those numbers are unreliable.[91]

Montenegro

The irredentist claims in Montenegro are in the border areas, including Kraja, Ulcinj, Tuzi (Malësia), Plav and Gusinje, and Rožaje (Sandžak).[92][93] According to the 2011 census, the Albanian proportion in those municipalities are following: Ulcinj–14,076 (70%), Tuzi–2,383 (50%), Plav–(19%), Rožaje–188 (2%). The claim on the Sandžak area, where the Albanian community is small and the Bosniak community is the majority, is based on the Albanian state borders in World War II and presence in the late Ottoman period.

North Macedonia

The western part of North Macedonia is an area with a large ethnic Albanian minority. The Albanian population in North Macedonia make up 25% of the population, numbering 509,083 in the 2002 census.[94][95] Cities with Albanian majorities or large minorities include Tetovo (Tetova), Gostivar (Gostivari), Struga (Struga) and Debar (Diber).[96]

In the 1980s, Albanian irredentist organizations appeared in the SR Macedonia, particularly Vinica, Kicevo, Tetovo and Gostivar.[97] In 1992, Albanian activists in Struga proclaimed also the founding of the Republic of Ilirida (Albanian: Republika e Iliridës)[98] with the intention of autonomy or federalization inside Macedonia. The declaration had only a symbolic meaning and the idea of an autonomous State of Ilirida is not officially accepted by the ethnic Albanian politicians in North Macedonia.[99][100]

Preševo Valley

The irredentist claims in Central Serbia (excluding Kosovo) are in the southern Preševo Valley, including municipalities of Preševo (Albanian: Preshevë), Bujanovac (Albanian: Bujanoc) and partially Medveđa (Albanian: Medvegjë), where there is an Albanian community. In 2001, the Albanians were estimated to have numbered 70,000 in the area.[101] According to the 2002 census, the Albanian proportion in those municipalities were following: Preševo–31,098 (89%), Bujanovac–23,681 (55%), Medveđa–2,816 (26%).

Following the Kosovo War (1998–99), the Albanian separatist Liberation Army of Preševo, Medveđa and Bujanovac (Albanian: Ushtria Çlirimtare e Preshevës, Medvegjës dhe Bujanocit, UÇPMB), fought an insurgency against the Serbian government, aiming to seceding the Preševo Valley into Kosovo.[102]

Greece

The irredentist claim in Greece are Chameria, parts of Epirus, the historical Vilayet of Janina.[3][4][5][6][7]

The coastal region of Thesprotia in northwestern Greece referred to by Albanians as Çamëria is sometimes included in Greater Albania.[12] According to the 1928 census held by the Greek state, there were around 20,000 Muslim Cams in Thesprotia prefecture. They were forced to seek refuge in Albania at the end of World War II after a large part of them collaborated and committed a number of crimes together with the Nazis during the 1941–1944 period.[103] In the first post-war census (1951), only 123 Muslim Çams were left in the area. Descendants of the exiled Muslim Chams (they claim that they are now up to 170,000 now living in Albania) claim that up to 35,000 Muslim Çams were living in southern Epirus before World War II. Many of them are currently trying to pursue legal ways to claim compensation for the properties seized by Greece. For Greece the issue "does not exist".[104]

International Crisis Group research

International Crisis Group researched the issue of Pan-Albanianism and published a report titled "Pan-Albanianism: How Big a Threat to Balkan Stability?" on February 2004.[105]

The International Crisis Group advised in the report the Albanian and Greek governments to endeavour and settle the longstanding issue of the Chams displaced from Greece in 1945, before it gets hijacked and exploited by extreme nationalists, and the Chams' legitimate grievances get lost in the struggle to further other national causes. Moreover, the ICG findings suggest that Albania is more interested in developing cultural and economic ties with Kosovo and maintaining separate statehood.[106]

See also

Notes

| a. | ^ Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Kosovo and the Republic of Serbia. The Republic of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence on 17 February 2008. Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. The two governments began to normalise relations in 2013, as part of the 2013 Brussels Agreement. Kosovo is currently recognized as an independent state by 98 out of the 193 United Nations member states. In total, 113 UN member states recognized Kosovo at some point, of which 15 later withdrew their recognition. |

References

Citations

- Dennison I. Rusinow (1978). The Yugoslav Experiment 1948–1974. Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-52003-730-4.

- Likmeta, Besar (17 November 2010). "Poll Reveals Support for 'Greater Albania'". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

The poll, conducted by Gallup in cooperation with the European Fund for the Balkans, showed that 62 per cent of respondents in Albania, 81 per cent in Kosovo and 51.9 per cent of respondents in Macedonia supported the formation of a Greater Albania.

- Merdjanova 2013, p. 147.

- Kola 2003, p. 15.

- Seton-Watson 1917, p. 189.

- Austin 2004, p. 237.

- Vaknin 2000, pp. 102–103.

- Jelavich 1983, pp. 361–365.

- Zolo 2002, p. 24. "It was under the Italian and German occupation of 1939–1944 that the project of Greater Albania... was conceived."

- Bugajski 2002, p. 675."Roughly half of the predominantly Albanian territories and 40% of the population were left outside the new country's borders"

- Judah 2008, p. 120.

- Bogdani & Loughlin 2007, pp. 230.

- "Alternativat e ribashkimit kombëtar të shqiptarëve dhe të Shqipërisë Etnike..!". Gazeta Ditore (in Albanian). 10 December 2012. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- Puto & Maurizio 2015, p. 183."Nineteenth-century Albanianism was not by any means a separatist project based on the desire to break with the Ottoman Empire and to create a nationstate. In its essence Albanian nationalism was a reaction to the gradual disintegration of the Ottoman Empire and a response to the threats posed by Christian and Balkan national movements to a population that was predominantly Muslim. In this sense, its main goal was to gather all 'Albanian' vilayet's into an autonomous province inside the Ottoman Empire. In fact, given its focus on the defence of the language, history and culture of a population spread across various regions and states, from Italy to the Balkans, it was not associated with any specific type of polity, but rather with the protection of its rights within the existing states. This was due to the fact that, culturally, early Albanian nationalists belonged to a world in which they were at home, though poised between different languages, cultures, and at times even states."

- Shaw & Shaw 1977, p. 288.

- Kostov 2010, p. 40. "These scholars did not have access to many primary sources to be able to construct the notion of the Illyrian origin of the Albanians yet, and Greater Albania was not a priority. The goal of the day was to persuade the Ottoman officials that Albanians were a nation and they deserved some autonomy with the Empire. In fact, Albanian historians and politicians were very moderate compared to their peers in neighbouring countries.

- Goldwyn 2016, p. 276.

- Gawrych 2006, pp. 197–200.

- Fischer 2007a, p. 19.

- Vickers 2011, pp. 69–76.

- Tanner 2014, pp. 168–172.

- Despot 2012, p. 137.

- Kronenbitter 2006, p. 85.

- Ker-Lindsay 2009, pp. 8–9.

- Jelavich 1983, pp. 100–103.

- Guy 2007, p. 453.

- Fischer 2007a, p. 21.

- Volkan 2004, p. 237.

- Guy 2007, p. 454. "Benckendorff, on the other hand, proposed only a truncated coastal strip to form a central Muslim dominated Albania, in accordance with the common view amongst Slavs, and also Greeks, that only Muslims could be considered Albanian (and not even Muslims necessarily)."

- Gingeras 2009, p. 31.

- Fischer 1999, pp. 5, 21–25.

- Fischer 1999, pp. 70–71.

- Fischer 1999, pp. 88,260.

- Hall 2010, p. 183.

- Judah 2008, p. 47.

- Rossos 2013, pp. 185–186.

- Fischer 1999, pp. 115–116, 260.

- Ramet 2006, pp. 141–142.

- Fischer 1999, p. 237.

- Denitch 1996, p. 118.

- Ramet 2006, p. 114.

- Judah 2002, p. 27.

- Ramón 2015, p. 262.

- Fontana 2017, p. 92.

- Fischer 1999, p. 260.

- Judah 2002, pp. 29–30.

- Judah 2002, pp. 30.

- Denitch 1996, p. 118.

- Turnock 2004, pp. 447.

- Batkovski & Rajkocevski 2014, p. 95.

- "see map". transindex.ro. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009.

- State-building in Kosovo. A plural policing perspective. Maklu. 5 February 2015. p. 53. ISBN 9789046607497.

- Liberating Kosovo: Coercive Diplomacy and U. S. Intervention. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. 2012. p. 69. ISBN 9780262305129.

- Dictionary of Genocide. Greenwood Publishing Group. 2008. p. 249. ISBN 9780313346415.

- "Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA)". Encyclopædia Britannica. 14 September 2014. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- Karon, Tony (6 March 2001). "Albanian Insurgents Keep NATO Forces Busy". Time. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016.

- Liberating Kosovo: Coercive Diplomacy and U. S. Intervention. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. 2012. p. 69. ISBN 9780262305129.

- Allan & Zelizer 2004, p. 178.

- UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo – 4. March–June 1999: An Overview Archived 3 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Hrw.org. Retrieved on 14 March 2013.

- Perlez, Jane (24 March 1999). "Conflict in the Balkans: The Overview; Nato Authorizes Bomb Strikes; Primakov, In Air, Skips U.S. Visit". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- "Kosovo war chronology". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 28 August 2010.

- "The Balkan wars: Reshaping the map of south-eastern Europe". The Economist. 9 November 2012. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- "Kosovo one year on". BBC. 16 March 2000. Archived from the original on 20 April 2010. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- Huggler, Justin (12 March 2001). "KLA veterans linked to latest bout of violence in Macedonia". The Independent. London. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- Stojarova 2010, p. 49.

- Banks, Muller & Overstreet 2010, p. 22.

- Schmid 2011, p. 401.

- Koktsidis & Dam 2008, p. 180.

- Vickers 2002, pp. 12–13.

- Stojarová 2016, p. 96.

- Austin 2004, p. 246.

- Endresen 2016, p. 208.

- Schwartz 2014, pp. 111–112.

- Venner 2016, p. 75.

- Merdjanova 2013, p. 49.

- "Dua Lipa sparks controversy with 'Greater Albania' map tweet". BBC. 20 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Maričić, Slobodan (19 July 2020). "Dua Lipa, Kosovo i Srbija: O Eplu, granicama i tome ko je prvi došao". BBC (in Serbian). Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Milton, Josh (20 July 2020). "Absolutely nobody had 'Dua Lipa comes out as an Albanian nationalist' on their 2020 bingo cards, so everyone is confused". PinkNews. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Savitsky, Shane (20 July 2020). "Dua Lipa courts controversy with tweet backing Albanian nationalism". AXIOS. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Gallup Balkan Monitor Archived 27 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 2010

- Balkan Insight Poll Reveals Support for 'Greater Albania' , 17 November 2010

- "Early Warning Report: Kosovo – Report # 15" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. October–December 2006. p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2007.

- Jelavich 1983, pp. 361.

- "Albright warns Albania against expansion". BBC News. 19 February 2000. Archived from the original on 22 October 2014.

- "Lëvizja Vetëvendosje" (PDF). Lëvizja Vetëvendosje. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- "Aleanca Kuq e Zi". Archived from the original on 17 October 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- Albania celebrates 100 years of independence, yet angers half its neighbors Associated Press, 28 November 2012.

- "Macedonia: Authorities Allege Existence of New Albanian Rebel Group". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- "Population and Housing Census 2011". INSTAT (Albanian Institute of Statistics). Archived from the original on 3 August 2017.

- CIA. "The World Factbook". Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- CIA. "The World Factbook". Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- Branko Petranović (2002). The Yugoslav Experience of Serbian National Integration. East European Monographs. ISBN 978-0-88033-484-6.

... unite with Albania, and to form the second Albanian state outside Yugoslavia, which would gather the Albanians of Kosovo and Metohija, western Macedonia and the border regions of Montenegro from Plav, Gusinje and Rozaje, through Tuzi, near the Montenegrin capital, the hinterland of Lake Skadar (Krajina) up to Ulcinj.

- Kenneth Morrison (11 January 2018). Nationalism, Identity and Statehood in Post-Yugoslav Montenegro. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-4742-3520-4.

- Macedonian Census (2002), Book 5 – Total population according to the Ethnic Affiliation, Mother Tongue and Religion Archived 27 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine, The State Statistical Office, Skopje, 2002, p. 62.

- "The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- Unrepresented Nations & Peoples Organization, Yearbook 1995 Page 41 By Mary Kate Simmons ISBN 90-411-0223-X

- Sabrina P. Ramet (1995). Social Currents in Eastern Europe: The Sources and Consequences of the Great Transformation. Duke University Press. p. 203. ISBN 0-8223-1548-3.

- Ramet 1997, p. 80.

- Bugajski 1994, pp. 116.

- "Macedonia: Authorities Allege Existence of New Albanian Rebel Group". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017.

- Partos, Gabriel (2 February 2001). "Presevo valley tension". BBC. Archived from the original on 23 October 2007. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

Initially, the guerrillas' publicly acknowledged objective was to protect the local ethnic Albanian population of some 70,000 people from the repressive actions of the Serb security forces.

- Rafael Reuveny; William R. Thompson (5 November 2010). Coping with Terrorism: Origins, Escalation, Counterstrategies, and Responses. SUNY Press. p. 185. ISBN 978-1-4384-3313-4.

- Meyer 2008, p. 702.

- "The Cham Issue – Where to Now?" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2008. Retrieved 22 February 2008.

Despite the Cham-induced controversy, during a visit to Albania in mid-October 2004, Greek President Konstantinos Stephanopoulos stated at a news conference that the Cham issue did not exist for Greece and that claims for the restoration of property presented by both the Cham people and the Greek minority in Albania belonged to a past historical period which he considered closed. "I don't know if it is necessary to find a solution to the Cham issue, as in my opinion it does not need to be solved," he said. "There have been claims from both sides, but we should not return to these matters. The question of the Cham properties does not exist," he said. When speaking of claims from both sides, Stephanopoulos was referring (also) to the Greek claims over Northern Epirus, which include a considerable part of southern Albania.

- "The Cham Issue – Where to Now?" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2008. Retrieved 22 February 2008.

Cham demonstrators was enough to galvanise Greece into defensive mode. The country embarked upon a series of military and diplomatic initiatives, which suggested a fear of Pan-Albanian expansion towards north-western Greece. Serbian and Macedonian media reports were claiming that new Pan-Albanian organisations were planning to expand their operations into north-western Greece to include Meanwhile, Chameria in their plans for the unification of "all Albanian territories." international observers were concerned that Kosovo politicians might start speculating with the Cham issue. The report observed that the "notions of pan-Albanianism are far more layered and complex than the usual broad brush characterisations of ethnic Albanians simply bent on achieving a greater Albania or a greater Kosovo." Furthermore, the report stated that amongst Albanians, "violence in the cause of a greater Albania, or of any shift of borders, is neither politically popular nor morally justified.

- "Pan-Albanianism: How Big a Threat to Balkan Stability?, Europe Report N°153, 25 February 2004". Archived from the original on 9 May 2007.

Sources

- Allan, Stuart; Zelizer, Barbie (2004). Reporting war: Journalism in wartime. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415339971.

- Austin, Robert C. (2004). "Greater Albania: The Albanian state and the question of Kosovo". In Lampe, John; Mazower, Mark (eds.). Ideologies and national identities: The case of twentieth-century Southeastern Europe. Budapest: Central European University Press. pp. 235–253. ISBN 9789639241824.

- Banks, A.; Muller, Thomas C.; Overstreet, William R. (2010). Political Handbook of the World. Washington D.C.: CQ Press. ISBN 9781604267365.

- Batkovski, Tome; Rajkocevski, Rade (2014). "Psychological Profile and Types of Leaders of Terrorist Structures - Generic Views and Experiences from the Activities of Illegal Groups and Organizations in the Republic of Macedonia". In Milosevic, Marko; Rekawek, Kacper (eds.). Perseverance of Terrorism: Focus on Leaders. Amsterdam: IOS Press. pp. 84–102. ISBN 9781614993872.

- Bogdani, Mirela; Loughlin, John (2007). Albania and the European Union: the tumultuous journey towards integration and accession. London: IB Tauris. ISBN 9781845113087.

- Bugajski, Janusz (1994). Ethnic politics in Eastern Europe: A guide to nationality policies, organizations, and parties. Armonk: ME Sharpe. p. 116. ISBN 9781315287430.

- Bugajski, Janusz (2002). Political Parties of Eastern Europe: A Guide to Politics in the Post-Communist Era. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 9781563246760.

- Denitch, Bogdan Denis (1996). Ethnic nationalism: The tragic death of Yugoslavia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. p. 117. ISBN 9780816629473.

- Despot, Igor (2012). The Balkan Wars in the Eyes of the Warring Parties: Perceptions and Interpretations. Bloomington: iUniverse. ISBN 9781475947038.

- Endresen, Cecile (2016). "Status Report Albania 100 Years: Symbolic Nation-Building Completed". In Kolstø, Pål (ed.). Strategies of Symbolic Nation-building in South Eastern Europe. Farnham: Routledge. pp. 201–226. ISBN 9781317049364.

- Fischer, Bernd Jürgen (1999). Albania at war, 1939–1945. London: Hurst & Company. ISBN 9781850655312.

- Fischer, Bernd Jürgen (2007a). "King Zog, Albania's Interwar Dictator". In Fischer, Bernd Jürgen (ed.). Balkan strongmen: dictators and authoritarian rulers of South Eastern Europe. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. pp. 19–50. ISBN 9781557534552.

- Fontana, Giuditta (2017). Education policy and power-sharing in post-conflict societies: Lebanon, Northern Ireland, and Macedonia. Birmingham: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 9783319314266.

- Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. ISBN 9781845112875.

- Gingeras, Ryan (2009). Sorrowful Shores: Violence, Ethnicity, and the End of the Ottoman Empire 1912-1923. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199561520.

- Goldwyn, Adam J. (2016). "Modernism, Nationalism, Albanianism: Geographic Poetry and Poetic Geography in the Albanian and Kosovar Independence Movements". In Goldwyn, Adam J.; Silverman, Renée M. (eds.). Mediterranean Modernism: Intercultural Exchange and Aesthetic Development. Springer. pp. 251–282. ISBN 9781137586568.

- Guy, Nicola C. (2007). "Linguistic boundaries and geopolitical interests: the Albanian boundary commissions, 1878–1926". Journal of Historical Geography. 34 (3): 448–470. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2007.12.002.

- Hall, Richard C. (2010). Consumed by war: European conflict in the 20th century. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813159959.

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983). History of the Balkans: Eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 361. ISBN 9780521274586.

- Judah, Tim (2002). Kosovo: War and revenge. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300097252.

- Judah, Tim (2008). Kosovo: What everyone needs to know. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199704040.

- Ker-Lindsay, James (2009). Kosovo: the path to contested statehood in the Balkans. London: IB Tauris. ISBN 9780857714121.

- Kola, Paulina (2003). The Search for Greater Albania. London: C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 9781850655961.

- Kostov, Chris (2010). Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto 1900-1996. Oxford: Peter Lang. ISBN 9783034301961.

- Koktsidis, Pavlos Ioannis; Dam, Caspar Ten (2008). "A success story? Analysing Albanian ethno-nationalist extremism in the Balkans" (PDF). East European Quarterly. 42 (2): 161–190.

- Kronenbitter, Günter (2006). "The militarization of Austrian Foreign Policy on the Eve of World War I". In Bischof, Günter; Pelinka, Anton; Gehler, Michael (eds.). Austrian Foreign Policy in Historical Context. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9781412817684.

- Meyer, Hermann Frank (2008). Blutiges Edelweiß: Die 1. Gebirgs-division im zweiten Weltkrieg. Berlin: Links Verlag. ISBN 9783861534471.

- Puto, Artan; Maurizio, Isabella (2015). "From Southern Italy to Istanbul: Trajectories of Albanian Nationalism in the Writings of Girolamo de Rada and Shemseddin Sami Frashëri, ca. 1848–1903". In Maurizio, Isabella; Zanou, Konstantina (eds.). Mediterranean Diasporas: Politics and Ideas in the Long 19th Century. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781472576668.

- Merdjanova, Ina (2013). Rediscovering the Umma: Muslims in the Balkans between nationalism and transnationalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190462505.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (1997). Whose Democracy? Nationalism, Religion, and the Doctrine of Collective rights in post-1989 eastern Europe. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780847683246.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The three Yugoslavias: State-building and legitimation, 1918–2005. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.

- Ramón, Juan Corona (2015). "Kosovo: Estado actual de una balcanización permanente". In Weber, Algora; Dolores, María (eds.). Minorías y fronteras en el mediterráneo ampliado. Un desafío a la seguridad internacional del siglo XXI. Madrid: Dykinson. pp. 259–272. ISBN 9788490857250.

- Rossos, Andrew (2013). Macedonia and the Macedonians: A history. Stanford: Hoover Institution Press. ISBN 9780817948832.

- Schmid, Alex P. (2011). The Routledge Handbook of Terrorism Research. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781136810404.

- Schwartz, Stephan (2014). "'Enverists' and 'Titoists' – Communism and Islam in Albania and Kosova, 1941–99: From the Partisan Movement of the Second World War to the Kosova Liberation War". In Fowkes, Ben; Gökay, Bülent (eds.). Muslims and Communists in Post-transition States. New York: Routledge. pp. 86–112. ISBN 9781317995395.

- Seton-Watson, Robert William (1917). The Rise of Nationality in the Balkans. New York: E. P. Dutton and Company. ISBN 9785877993853.

- Shaw, Stanford J.; Shaw, Ezel Kural (1977). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey: Volume 2, Reform, Revolution, and Republic: The Rise of Modern Turkey 1808-1975. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521291668.

- Stojarova, Vera (2010). "Nationalist parties and the party systems of the Western Balkans". In Stojarova, Vera; Emerson, Peter (eds.). Party politics in the Western Balkans. New York: Routledge. pp. 42–58. ISBN 9781135235857.

- Stojarová, Vera (2016). The far right in the Balkans. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781526117021.

- Tanner, Marcus (2014). Albania's mountain queen: Edith Durham and the Balkans. London: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781780768199.

- Turnock, David (2004). The economy of East Central Europe, 1815-1989: Stages of transformation in a peripheral region. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781134678761.

- Vaknin, Samuel (2000). After the Rain: How the West Lost the East. Skopje: Narcissus Publishing. ISBN 9788023851731.

- Venner, Mary (2016). Donors, Technical Assistance and Public Administration in Kosovo. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781526101211.

- Vickers, Miranda (2002). The Cham Issue - Albanian National & Property Claims in Greece (Report). Swindon: Defence Academy of the United Kingdom.

- Vickers, Miranda (2011). The Albanians: A modern history. London: IB Tauris. ISBN 9780857736550.

- Volkan, Vamik (2004). Blind trust: Large groups and their leaders in times of crisis and terror. Charlottesville: Pitchstone Publishing. ISBN 9780985281588.

- Zolo, Danilo (2002). Invoking humanity: War, law and global order. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9780826456564.

Further reading

- Canak, Jovan M. Greater Albania: concepts and possibile [sic] consequences. Belgrade: Institute of Geopolitical Studies, 1998.

- Jaksic G. and Vuckovic V. Spoljna politika srbije za vlade. Kneza Mihaila, Belgrade, 1963.

- Dimitrios Triantaphyllou. The Albanian Factor. ELIAMEP, Athens, 2000.

- Mandelbaum, Michael (1998). The new European diasporas: national minorities and conflict in Eastern Europe. Council on Foreign Relations Press, New York. ISBN 9780876092576.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Greater Albania. |

- Albanian Canadian League Information Service (ACLIS)

- Perspective: Albania and Kosova by Van Christo

- High Albania by M. Edith Durham

- Albanian Identities by Antonina Zhelyazkova

- The Kosovo Chronicles by Dusan Batakovic

- Albania and Kosovo | What happened to Greater Albania?, The Economist, 18 January 2007