Gutian people

The Guti (/ˈɡuːti/) or Quti, also known by the derived exonyms Gutians or Guteans, were a nomadic people of West Asia, around the Zagros Mountains (Modern Iran) during ancient times. Their homeland was known as Gutium (Sumerian: 𒄖𒌅𒌝𒆠,Gu-tu-umki or 𒄖𒋾𒌝𒆠,Gu-ti-umki).[1][2]

Bottom: Approximate location of original Gutium territory

Conflict between people from Gutium and the Akkadian Empire has been linked to the collapse of the empire, towards the end of the 3rd millennium BC. The Guti subsequently overran southern Mesopotamia and formed the Gutian dynasty of Sumer. The Sumerian king list suggests that the Guti ruled over Sumer for several generations following the fall of the Akkadian Empire.[3]

By the 1st millennium BC, usage of the name Gutium, by the peoples of lowland Mesopotamia, had expanded to include all of western Media, between the Zagros and the Tigris. Various tribes and places to the east and northeast were often referred to as Gutians or Gutium.[4] For example, Assyrian royal annals use the term Gutians in relation to populations known to have been Medes or Mannaeans. As late as the reign of Cyrus the Great of Persia, the famous general Gubaru (Gobryas) was described as the "governor of Gutium".

Origin

Little is known of the origins, material culture or language of the Guti, as contemporary sources provide few details and no artifacts have been positively identified.[5] As the Gutian language lacks a text corpus, apart from some proper names, its similarities to other languages are impossible to verify. The names of Gutian-Sumerian kings suggest that the language was not closely related to any languages of the region, including Sumerian, Akkadian, Hurrian, Hittite, and Elamite.

W. B. Henning suggested that the different endings of the king names resembled case endings in the Tocharian languages, a branch of Indo-European known from texts found in the Tarim Basin (in the northwest of modern China) dating from the 6th to 8th centuries BC, making Gutian the earliest documented Indo-European language. He further suggested that they had subsequently migrated to the Tarim.[6] Gamkrelidze and Ivanov explored Henning's suggestion, as possibly supporting their proposal of an Indo-European Urheimat in the Near East.[7][8] However, most scholars reject the attempt to connect two groups of languages, Gutian and Tocharian, that were separated by more than two millennia.[9]

History

Overview

Since Gutian appears to have been an unwritten language, for information about the Guti, scholars must rely on external sources – often highly biased texts composed by their enemies. For example, Sumerian sources generally portray the Guti as an "unhappy", barbarous and rapacious people from the mountains – apparently the central Zagros east of Babylon and north of Elam.[10] The period of the Gutian dynasty in Sumer is portrayed as chaotic.

Initially, according to the Sumerian king list, "in Gutium ... no king was famous; they were their own kings and ruled thus for three [or five] years".[11] This may indicate that the Gutian kingship was rotated between tribes/clans, or within an oligarchical elite.

25th to 23rd centuries BC

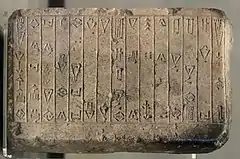

The Guti appear in texts from Old Babylonian copies of inscriptions ascribed to Lugal-Anne-Mundu (fl. circa 25th century BC) of Adab as among the nations providing his empire tribute. These inscriptions locate them between Subartu in the north, and Marhashe and Elam in the south. They were a prominent nomadic tribe who lived in the Zagros mountains in the time of the Akkadian Empire.

Sargon the Great (r. circa 2340 – 2284 BC) also mentions them among his subject lands, listing them between Lullubi, Armanum and Akkad to the north; Nikku and Der to the south. According to one stele, Naram-Sin of Akkad's army of 360,000 soldiers defeated the Gutian king Gula'an, despite having 90,000 slain by the Gutians.

The epic Cuthean Legend of Naram-Sin claims Gutium among the lands raided by Annubanini of Lulubum during the reign of Naram-Sin (c. 2254–2218 BC).[14] Contemporary year-names for Shar-kali-sharri of Akkad indicate that in one unknown year of his reign, Shar-kali-sharri captured Sharlag king of Gutium, while in another year, "the yoke was imposed on Gutium".[15]

Prominence during the early 22nd century BC

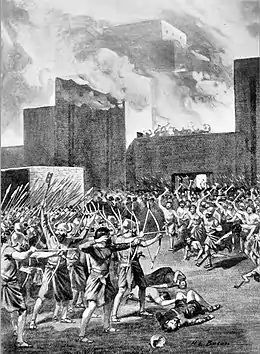

As the Akkadians went into decline, the Gutians began a campaign, decades-long of hit-and-run raids against Mesopotamia. Their raids crippled the economy of Sumer. Travel became unsafe, as did work in the fields, resulting in famine. The Gutians eventually overran Akkad, and as the King List tells us, their army also subdued Uruk for hegemony of Sumer, in about 2147–2050 BC. However, it seems that autonomous rulers soon arose again in a number of city-states, notably Gudea of Lagash.

The Gutians seem also to have briefly overrun Elam at around the same time, towards the close of Kutik-Inshushinak's reign (c. 2100 BC).[17] On a statue of the Gutian king Erridupizir at Nippur, an inscription imitates his Akkadian predecessors, styling him "King of Gutium, King of the Four Quarters".

The Weidner Chronicle (written c. 500 BC), portrays the Gutian kings as uncultured and uncouth:

Naram-Sin destroyed the people of Babylon, so twice Marduk summoned the forces of Gutium against him. Marduk gave his kingship to the Gutian force. The Gutians were unhappy people unaware how to revere the gods, ignorant of the right cultic practices. Utu-hengal, the fisherman, caught a fish at the edge of the sea for an offering. That fish should not be offered to another god until it had been offered to Marduk, but the Gutians took the boiled fish from his hand before it was offered, so by his august command, Marduk removed the Gutian force from the rule of his land and gave it to Utu-hengal.

Decline from the late 22nd century BC onwards

The Sumerian ruler Utu-hengal, Prince of the Sumerian city of Uruk is similarly credited on the King List with defeating the Gutian ruler Tirigan, and removing the Guti from the country in circa 2050 BC (short chronology).[11]

In his Victory Stele, Utu-hengal wrote about the Gutians:

.jpg.webp)

Gutium, the fanged snake of the mountain ranges, a people who acted violently against the gods, people who the kingship of Sumer to the mountains took away, who Sumer with wickedness filled, who from one with a wife his wife took away from him, who from one with a child his child took away from him, who wickedness and violence produced within the country..."

Following this, Ur-Nammu of Ur ordered the destruction of Gutium. The year 11 of king Ur-Nammu also mentions "Year Gutium was destroyed".[20] However, according to a Sumerian epic, Ur-Nammu died in battle with the Gutians, after having been abandoned by his own army.

A Babylonian text from the early 2nd millennium refers to the Guti as having a "human face, dogs’ cunning, [and] monkey's build".[4]

Biblical scholars believe that the Guti may be the "Koa" (qôa), named with the Shoa and Pekod as enemies of Jerusalem in Ezekiel 23:23,[21] which was probably written in the 6th century BC. Qôa also means "male camel" in Hebrew, and in the context of Ezekiel 23, it may be a deliberate, insulting distortion of an endonym such as Quti.

Physical appearance

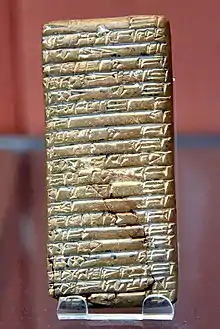

According to the historian Henry Hoyle Howorth (1901), Assyriologist Theophilus Pinches (1908), renowned archaeologist Leonard Woolley (1929) and Assyriologist Ignace Gelb (1944), the Gutians were pale in complexion and blond. But this was asserted on the basis of assumed broad links to peoples mentioned in the Old Testament.[24][25][26][27] This identification of the Gutians as fair haired first came to light when Julius Oppert (1877) published a set of tablets he had discovered which described Gutian (and Subarian) slaves as namrum or namrûtum, one of its many meanings being "light colored".[28][29] This racial character of the Gutians as light skinned cannot be equated to being blond. But yet it was also claimed by Georges Vacher de Lapouge in 1899 and later by historian Sidney Smith in his Early History of Assyria (1928).[30][31]

Ephraim Avigdor Speiser, however, criticised the translation of namrum as "light colored". A note was published by Speiser in the Journal of the American Oriental Society criticizing Gelb's translation and consequent interpretation.[32] Gelb in response accused Speiser of circular reasoning.[33] In response, Speiser claimed the scholarship regarding the translation of namrum or namrûtum is unresolved.[34]

Gutian rulers

| Ruler | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Inkishush (or Inkicuc) | 6 years | c. 2147–2050 BC (short) | ||

| Sarlagab (or Zarlagab) | 6 years | Was taken prisonner by Sharkalisharri in the year 11 of the latter's reign: "the year in which Szarkaliszarri (...) took prisoner Szarlag(ab) the king of Gutium"[35] | ||

| Shulme (or Yarlagash) | 6 years | |||

| Elulmesh (or Silulumesh or Silulu) | 6 years | |||

| Inimabakesh (or Duga) | 5 years | |||

| Igeshaush (or Ilu-An) | 6 years | |||

| Yarlagab | 3 years | |||

| Ibate of Gutium | 3 years | |||

| Yarla (or Yarlangab) | 3 years | |||

| Kurum | 1 year | |||

| Apilkin | 3 years | |||

| La-erabum | 2 years | mace head inscription | ||

| Irarum | 2 years | |||

| Ibranum | 1 year | |||

| Hablum | 2 years | |||

| Puzur-Suen | 7 years | "the son of Hablum" | ||

| Yarlaganda | 7 years | foundation inscription at Umma | ||

| Si'um or Si-u? | 7 years | foundation inscription at Umma | ||

| Tirigan | 40 days | defeated by Utu-hengal of Uruk | ||

| ||||

Modern connection theories

The historical Guti have been regarded by several scholars as having contributed to the ethnogenesis of the Kurds.[36][37][38]

Faravahar background |

| History of Greater Iran |

|---|

References

- ETCSL. The Sumerian King List Archived 2010-08-30 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 19 Dec 2010.

- ETCSL. The Cursing of Agade Accessed 18 Dec 2010.

- ETCSL - Sumerian king list

- Van De Mieroop, Marc. "GUTIANS". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- Patton, Laurie L., et al. (2004) The Indo-Aryan Controversy

- Henning, W.B. (1978). "The first Indo-Europeans in history". In Ulmen, G.L. (ed.). Society and History, Essays in Honour of Karl August Wittfogel. The Hague: Mouton. pp. 215–230. ISBN 978-90-279-7776-2.

- Gamkrelidze, T.V.; Ivanov, V.V. (1989). "Первые индоевропейцы на арене истории: прототохары в Передней Азии" [The first Indo-Europeans in history: the proto-Tocharians in Asia Minor]. Journal of Ancient History (1): 14–39.

- Gamkrelidze, T.V.; Ivanov, V.V. (2013). "Индоевропейская прародина и расселение индоевропейцев: полвека исследований и обсуждений" [Indo-European homeland and migrations: half a century of studies and discussions]. Journal of Language Relationship. 9: 109–136. doi:10.31826/jlr-2013-090111. S2CID 212688321.

- Mallory, J.P.; Mair, Victor H. (2000). The Tarim Mummies. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 281–282. ISBN 978-0-500-05101-6.

- Eller, Jack David (1999). Kurdish History and Kurdish Identity. p. 153. ISBN 978-0472085385.

- ETCSL - The victory of Utu-ḫeĝal

- Osborne, James F. (2014). Approaching Monumentality in Archaeology. SUNY Press. p. 123. ISBN 9781438453255.

- Edwards, I. E. S.; Gadd, C. J.; Hammond, N. G. L. (1971). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. p. 444. ISBN 978-0-521-07791-0.

- Reallexikon der Assyriologie und vorderasiatischen Archäologie By Erich Ebling, Bruno

- Year-names for Sharkalisharri

- The Sumerian Kings List (PDF). p. 119, note 305.

- Martin Sicker, 2000, The Pre-Islamic Middle East, p. 19,

- Full transcription and translation in: "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu.

- THUREAU-DANGIN, Fr. (1912). "La Fin de la Domination Gutienne". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 9 (3): 111–120. ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR 23283609.

- "Year names of Ur-Nammu". cdli.ucla.edu.

- See, for example, J. D. Douglas & Merrill C. Tenney, 2011, Zondervan Illustrated Bible Dictionary (3rd ed.), HarperCollins, p. 1897.

- "Old Akkadian Letters [CDLI Wiki]". cdli.ox.ac.uk.

- Enderwitz, Susanne; Sauer, Rebecca (2015). Communication and Materiality: Written and Unwritten Communication in Pre-Modern Societies. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 10. ISBN 978-3-11-037175-8.

- Howorth, Henry H. (1901). "The Early History of Babylonia". The English Historical Review. 16 (61): 1–34 [p. 32]. doi:10.1093/ehr/XVI.LXI.1. JSTOR 549506.

- Pinches, Theophilus Goldridge (2005) [1903]. The Old Testament in the Light of the Historical Records and Legends of Assyria and Babylonia (Reprint ed.). Kessinger. p. 158. OCLC 6230149.

- Woolley, Leonard (1929). The Sumerians. Clarendon Press. p. 5. OCLC 399045.

- Gelb (1944). Hurrians and Subarians. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization. University of Chicago Press. p. 88. OCLC 1545672.

- Gelb, 1944, p. 43

- Gelb, 1944, p. 88 - further translates a tablet passage as "a light (-coloured) slave girl who is pleasing to your eye."

- Vacher de Lapouge, Georges (1939). Der Arier und seine Bedeutung für die Gemeinschaft. M. Diesterweg. OCLC 19003462.

- Early History of Assyria. Vol. 1. 1928. p. 72.

...one notable physical trait the Subaraeans and Gutians shared. Documents of the period of the Babylonian Amorite or First Dynasty mention slaves from Gutium and Subir (that is, Subartu), and specify that they shall be of fair complexion.

- "Were the ancient Gutians really blond and Indo-Europeans?". JAOS. 50: 338. 1930. JSTOR 593093.

- Gelb 1944, p.43: "Speiser's...reaction against the normal interpretation of namrum as 'light (-colored)' was caused by... assumption that Hurrians or Subarians belonged to the Armenoid race, which according to them could hardly be called light-colored".

- Speiser, E. A. (1948). "Hurrians and Subarians". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 68 (1): 1–13 [p. 12]. doi:10.2307/596231. JSTOR 596231.

- "Year Names of Sharkalisharri [CDLI Wiki]". cdli.ox.ac.uk.

- Jamie Stokes, ed. (2009). "Kurds". Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East. Facts on File. p. 380. ISBN 9781438126760.

- D. P. Erdbrink (1968). "Reviewed Work: Türken, Kurden und Iraner seit dem Altertum by E. von Eickstedt". Central Asiatic Journal. Harrassowitz Verlag. 12 (1): 64–65. JSTOR 41926760.

- Prokhorov, Aleksandr Mikhaĭlovich (1982). "Great Soviet Encyclopedia".

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)