Harvard Art Museums

The Harvard Art Museums are part of Harvard University and comprise three museums: the Fogg Museum (established in 1895[1]), the Busch-Reisinger Museum (established in 1903[1]), and the Arthur M. Sackler Museum (established in 1985[1]) and four research centers: the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis (founded in 1958),[2] the Center for the Technical Study of Modern Art (founded in 2002),[3] the Harvard Art Museums Archives, and the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies (founded in 1928).[4] The three museums that constitute the Harvard Art Museums were initially integrated into a single institution under the name Harvard University Art Museums in 1983. The word "University" was dropped from the institutional name in 2008.

| |

Location within Boston | |

| Established | 1983 |

|---|---|

| Location | 32 Quincy Street Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States |

| Coordinates | 42.3742°N 71.1147°W |

| Type | Art museum |

| Collection size | over 250,000 |

| Director | Martha Tedeschi |

| Architect | Renzo Piano |

| Owner | Harvard University |

| Public transit access | Harvard |

| Website | harvardartmuseums |

The collections include approximately 250,000 objects in all media, ranging in date from antiquity to the present and originating in Europe, North America, North Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, East Asia, and Southeast Asia.

Renovation and expansion

In 2008, the Harvard Art Museums' historic building at 32 Quincy Street, Cambridge, was closed for a major renovation and expansion project. During the beginning phases of this project, the Arthur M. Sackler Museum at 485 Broadway, Cambridge, displayed selected works from the collections of the Fogg, Busch-Reisinger, and Sackler museums from September 13, 2008 through June 1, 2013.

The renovated building at 32 Quincy Street unites the three museums in a single state-of-the-art facility designed by architect Renzo Piano, which increases gallery space by 40% and adds a glass, pyramidal roof.[5] In a view of the front facade, the glass roof and other expansions are mostly concealed, largely preserving the original appearance of the building. The renovation was supervised by LeMessurier Consultants and Silman Associates.

The renovation adds six levels of galleries, classrooms, lecture halls, and new study areas providing access to parts of the 250,000-piece collection of the museums.[6] The new building was opened in November 2014.[7]

Directors

- Charles Herbert Moore: 1896–1909

- Edward W. Forbes: 1909–1944

- John Coolidge: 1948–1968

- Agnes Mongan: 1968–1971

- Daniel Robbins: 1972–1974

- Seymour Slive: 1975–1984

- Edgar Peters Bowron: 1985–1990

- James Cuno: 1991–2002

- Thomas W. Lentz: 2003–2015

- Martha Tedeschi: 2016–present

Fogg Museum

The Fogg Museum, opened to the public in 1896, is the oldest and largest component of the Harvard Art Museums.

History

The museum was originally housed in an Italian Renaissance-style building designed by Richard Morris Hunt. According to Donald Preziosi, the museum was not initially established as a gallery for the display of original works of art, but was founded as an institution for the teaching and study of visual arts, and the original building contained classrooms equipped with magic lanterns, a library, an archive of slides and photographs of art works, and exhibition space for reproductions of works of art.[8] In 1925, the building was replaced by a Georgian Revival-style structure on Quincy Street, designed by Coolidge, Shepley, Bulfinch, and Abbott. (The original Hunt Hall remained, underutilized until it was demolished in 1974 to make way for new freshman dormitories.[9])

Collection

The Fogg Museum is renowned for its holdings of Western paintings, sculpture, decorative arts, photographs, prints, and drawings from the Middle Ages to the present. Particular strengths include Italian Renaissance, British Pre-Raphaelite, and French art of the 19th century, as well as 19th- and 20th-century American paintings and drawings.

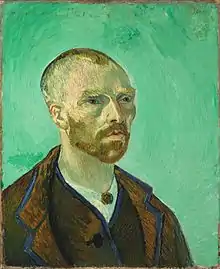

The museum's Maurice Wertheim Collection is a notable group of impressionist and post-impressionist works that contains many famous masterpieces, including paintings and sculptures by Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Vincent van Gogh. Central to the Fogg's holdings is the Grenville L. Winthrop Collection, with more than 4,000 works of art. Bequeathed to Harvard in 1943, the collection continues to play a pivotal role in shaping the legacy of the Harvard Art Museums, serving as a foundation for teaching, research, and professional training programs. It includes important 19th-century paintings, sculpture, and drawings by William Blake, Edward Burne-Jones, Jacques-Louis David, Honoré Daumier, Winslow Homer, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Alfred Barye, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Auguste Rodin, John Singer Sargent, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and James Abbott McNeill Whistler.

The art museum has Late Medieval Italian paintings by the Master of Offida,[10] Master of Camerino,[11] Bernardo Daddi, Simone Martini, Luca di Tomme, Pietro Lorenzetti, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Master of Orcanesque Misercordia, Master of Saints Cosmas and Damiançand Bartolomeo Bulgarini.

Flemish Renaissance paintings — Master of Catholic Kings, Jan Provoost, Master of Holy Blood, Aelbert Bouts, and Master of Saint Ursula.

Italian Renaissance period paintings — Fra Angelico, Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Gherardo Starnina, Cosme Tura, Giovanni di Paolo, and Lorenzo Lotto.

French Baroque period paintings — Nicolas Poussin, Jacques Stella, Nicolas Regnier, and Philippe de Champaigne.

Dutch Master paintings — Rembrandt, Emanuel de Witte, Jan Steen, Willem Van de Velde, Jacob Van Ruisdael, Salomon van Ruysdael, Jan van der Heyden, and Dirck Hals.

American paintings — Gilbert Stuart, Charles Willson Peale, Robert Feke, Sanford Gifford, James McNeil Whistler, John Singer Sargent, Thomas Eakins, Man Ray, Ben Shahn, Jacob Lawrence, Lewis Rubenstein, Robert Sloan, Phillip Guston, Jackson Pollock, Kerry James Marshall, and Clyfford Still.

Gallery

Titian, Rustic Idyll, 1507-1508

Titian, Rustic Idyll, 1507-1508.jpg.webp) Nicolas Poussin, Holy Family, 1645-1650

Nicolas Poussin, Holy Family, 1645-1650 Canaletto, Piazza San Marco, Venice, c. 1730-1735

Canaletto, Piazza San Marco, Venice, c. 1730-1735 John Singleton Copley, Mrs. Daniel Denison Rogers (Abigail Bromfield), 1784

John Singleton Copley, Mrs. Daniel Denison Rogers (Abigail Bromfield), 1784 Ammi Phillips, Harriet Leavens, c. 1815

Ammi Phillips, Harriet Leavens, c. 1815

Albert Bierstadt, In the Sierras, 1868

Albert Bierstadt, In the Sierras, 1868 Frédéric Bazille, Summer Scene, 1869

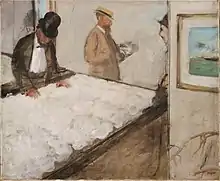

Frédéric Bazille, Summer Scene, 1869 Edgar Degas, Cotton Merchants in New Orleans, 1873

Edgar Degas, Cotton Merchants in New Orleans, 1873 Edgar Degas, The Rehearsal, 1873

Edgar Degas, The Rehearsal, 1873 Claude Monet, The Gare Saint-Lazare, Arrival of a Train, 1877

Claude Monet, The Gare Saint-Lazare, Arrival of a Train, 1877 Paul Gauguin, Self portrait, c. 1875-1877

Paul Gauguin, Self portrait, c. 1875-1877 Edgar Degas, The Singer with the Glove, 1878

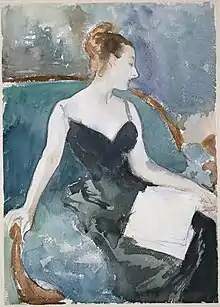

Edgar Degas, The Singer with the Glove, 1878 John Singer Sargent, Madame Gautreau (Madame X), c. 1883

John Singer Sargent, Madame Gautreau (Madame X), c. 1883 Vincent van Gogh, Three Pairs of Shoes, 1886

Vincent van Gogh, Three Pairs of Shoes, 1886

Paul Gauguin, Still Life with Apples, a Pear, and a Ceramic Portrait Jug, 1889

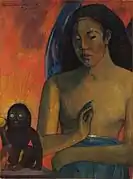

Paul Gauguin, Still Life with Apples, a Pear, and a Ceramic Portrait Jug, 1889 Paul Gauguin, Poèmes barbares, 1896

Paul Gauguin, Poèmes barbares, 1896 Thomas Eakins, Miss Alice Kurtz, 1903

Thomas Eakins, Miss Alice Kurtz, 1903%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_51.4_x_68.6_cm%252C_Fogg_Art_Museum%252C_Harvard_University.jpg.webp) Jean Metzinger, Landscape (Marine, Composition Cubiste), 1912

Jean Metzinger, Landscape (Marine, Composition Cubiste), 1912

Busch–Reisinger Museum

Founded in 1901 as the Germanic Museum, the Busch–Reisinger Museum is the only museum in North America dedicated to the study of art from the German-speaking countries of Central and Northern Europe in all media and in all periods.[12] William James spoke at its dedication.[13] Its holdings include significant works of Austrian Secession art, German expressionism, 1920s abstraction, and material related to the Bauhaus design school. Other strengths include late medieval sculpture and 18th-century art. The museum also holds noteworthy postwar and contemporary art from German-speaking Europe, including works by Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, Gerhard Richter, and one of the world's most comprehensive collections of works by Joseph Beuys.

The Busch–Reisinger Art Museum has oil paintings by artists Lovis Corinth, Max Liebermann, Gustav Klimt, Edvard Munch, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Max Ernst, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Franz Marc, Karl Schmidt-Rotluff, Emil Nolde, Erich Heckel, Heinrich Hoerle, Georg Baselitz, László Moholy-Nagy, and Max Beckmann. It has sculpture by Alfred Barye, Kathe Kollwitz, George Minne, and Ernst Barlach.

From 1921 to 1991, the Busch–Reisinger was located in Adolphus Busch Hall at 29 Kirkland Street. The Hall continues to house the Busch–Reisinger's founding collection of medieval plaster casts and an exhibition on the history of the Busch–Reisinger Museum; it also hosts concerts on its Flentrop pipe organ. In 1991, the Busch–Reisinger moved to the new Werner Otto Hall, designed by Gwathmey Siegel & Associates, at 32 Quincy Street.[12] In 2018, Busch–Reisinger featured "Inventur–Art in Germany, 1943–55", which was named after a 1945 poem by Günter Eich.[14]

Curators

- Kuno Francke, 1903–1930[15]

- Charles L. Kuhn, 1930–1968[16]

- Peter Nisbet

- Lynette Roth[17]

Arthur M. Sackler Museum

The Arthur M. Sackler Museum opened in 1985. The museum building, which was designed by British architect James Stirling, was named for the major donor, Arthur M. Sackler, a psychiatrist, entrepreneur, and philanthropist.[18] The museum also housed offices for the History of Art and Architecture faculty, as well as the Digital Images and Slides Collection of the Fine Arts Library. As of 2016, the old Sackler Museum building houses the History of Art and Architecture Department and the Media Slide Library.[12]

Collection

The museum collection holds important collections of Asian art, most notably, archaic Chinese jades (the widest collection outside of China) and Japanese surimono, as well as outstanding Chinese bronzes, ceremonial weapons, Buddhist cave-temple sculptures, ceramics from China and Korea, Japanese works on paper, and lacquer boxes,[19] and ancient Iranian metalwork.[20]

The ancient Mediterranean and Byzantine collections comprise significant works in all media from Greece, Rome, Egypt, and the Near East. Strengths include Greek vases, small bronzes, and coins from throughout the ancient Mediterranean world.

The museum also holds works on paper from Islamic lands and India, including paintings, drawings, calligraphy, and manuscript illustrations, with particular strength in Rajput art, as well as important Islamic ceramics from the 8th through to the 19th century.

Architecture

The Sackler Museum, originally designed as an extension to the Fogg, elicited worldwide attention from the time of Harvard's commission of Stirling to design the building, following a selection process that evaluated more than 70 architects.[21][22] As a measure of the excitement generated by the project, the University mounted an exhibition of the architects' preliminary design drawings in 1981, James Stirling's Design to Expand the Fogg Museum and issued a portfolio of Stirling's drawings to the press.

After completion, the building's coverage was even greater,[23] with general acknowledgment of the building's significance as a Stirling design and a Harvard undertaking. Stirling employed an inventive design in an effort to let the museum peacefully co-exist with neighboring buildings in an area that he termed "an architectural zoo".[21] Harvard published a 50-page book on the Sackler, with extensive color photos by Timothy Hursley, an interview with Stirling by Michael Dennis, a tribute to Arthur M. Sackler, and essays by Slive, Coolidge and Rosenfield.

In spite of global critical acclaim, a few have been critical, Martin Peretz even proposing demolition, though his case was undermined by mis-attributing the building to another British architect, Norman Foster.[24]

As of 2013, the future use of the building was unclear,[25] as its collection has been relocated to the Renzo Piano extension to the Fogg. Stirling's structure still stands as of December 2016. Since 1984, the building has housed the University's department of the History of Art + Architecture, with building renovations being completed in early 2019 to better accommodate the faculty and students.[26]

See also

References

- "History". Harvard Art Museums. Archived from the original on 2013-06-18. Retrieved 2013-07-20.

- "Archaeological Exploration of Sardis". Harvard Art Museums. Retrieved 2013-07-20.

- "Center for the Technical Study of Modern Art". Harvard Art Museums. Retrieved 2013-07-20.

- "Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies". Harvard Art Museums. 2008-02-18. Retrieved 2013-07-20.

- "After 6 years, Harvard Art Museums reemerging". Boston Globe. 12 April 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- "Renzo Piano reconfigures Harvard Art Museums around a grand courtyard atrium". Dezeen magazine. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- Farago, Jason (15 November 2014). "Renzo Piano reboot of Harvard art museums largely triumphs". The Guardian.

- Preziosi, Donald (Winter 1992). "The Question of Art History". Critical Inquiry. 18 (2): 363–386. doi:10.1086/448636. JSTOR 1343788.

- Harvard News Office (2002-04-04). "Harvard Gazette: Color, form, action and teaching". News.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2013-07-18.

The first Fogg Museum, known as Hunt Hall, was built in 1893 and demolished in 1974 to make way for Canaday. The "new" Fogg was built in 1925 where the home of Harvard naturalist Louis Agassiz once stood — the original Agassiz neighborhood. The building is named for William Hayes Fogg, a Maine merchant who was born in 1817, left school at 14, and grew rich in the China trade. After he died in 1884, his widow, Elizabeth, left $200,000 and the couple's Asian art collection to Harvard.

- "The Virgin and Child Enthroned; Christ on the Cross between the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist". Harvard Art Museums. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- "The Virgin and Child Enthroned". Harvard Art Museums. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- "History and the Three Museums". Harvard Art Museums. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- The Dedication of the Germanic Museum of Harvard University. Harvard University. Germanic Museum. German American Press. 1904. p. 28.

dedication germanic museum william james.

- Scharmann, Allison (February 12, 2018). "Inventur: Forgotten Art Rediscovered at the Harvard Art Museums". The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- Lenger, John. "Busch–Reisinger marks a century". The Harvard Gazette. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- "Busch–Reisinger's Kuhn to Retire After 38 Years as Museum Head". The Harvard Crimson. March 26, 1968. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- "Staff and Contact". Harvard Art Museums. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Glueck, Grace (October 18, 1985). "Sackler Art Museum to open at Harvard". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- "Arthur M Sackler Museum". Time Out North America. Retrieved July 30, 2012.

- Arthur M. Sackler Gallery (Smithsonian Institution);Gunter, Ann Clyburn;Jett (1992). "Ancient Iranian metalwork in the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and the Freer Gallery of Art". library.si.edu. Retrieved 2020-08-21.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Stapen, Nancy (October 28, 1985). "Harvard's startling Sackler. Challenge was to fit museum into 'architectural zoo' - CSMonitor.com". Csmonitor.com. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- Cannon-Brookes, Peter (September 1982). "James Stirling's design to expand the Fogg Museum". International Journal of Museum Management and Curatorship. 1 (3): 237–242. doi:10.1016/0260-4779(82)90056-5.

- Jennifer A. Kingson (October 22, 1984). "Warehouse or Museum?". Thecrimson.com. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- Peretz, Martin (29 June 2008). "A List Of Buildings To Demolish In Cambridge, Massachusetts". New Republic. Retrieved 2016-12-09.

- MacGregor, Brianna D. (September 26, 2013). "Sackler Building Faces Uncertain Future | News | The Harvard Crimson". www.thecrimson.com. Retrieved 2016-12-09.

- "About". haa.fas.harvard.edu. April 18, 2019.

Further reading

- Manuel, Steven (13 December 2014). "Connected Dialogues: experiencing Harvard Art Museums". ArtsEditor. Retrieved 11 January 2015. Review of the renovation

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Harvard Art Museums. |