Heart rate

Heart rate is the speed of the heartbeat measured by the number of contractions (beats) of the heart per minute (bpm). The heart rate can vary according to the body's physical needs, including the need to absorb oxygen and excrete carbon dioxide, but is also modulated by a myriad of factors including but not limited to genetics, physical fitness, stress or psychological status, diet, drugs, hormonal status, environment, and disease/illness as well as the interaction between and among these factors.[1] It is usually equal or close to the pulse measured at any peripheral point.

The American Heart Association states the normal resting adult human heart rate is 60–100 bpm.[2] Tachycardia is a high heart rate, defined as above 100 bpm at rest.[3] Bradycardia is a low heart rate, defined as below 60 bpm at rest. During sleep a slow heartbeat with rates around 40–50 bpm is common and is considered normal. When the heart is not beating in a regular pattern, this is referred to as an arrhythmia. Abnormalities of heart rate sometimes indicate disease.[4]

Physiology

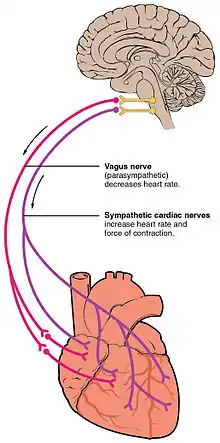

While heart rhythm is regulated entirely by the sinoatrial node under normal conditions, heart rate is regulated by sympathetic and parasympathetic input to the sinoatrial node. The accelerans nerve provides sympathetic input to the heart by releasing norepinephrine onto the cells of the sinoatrial node (SA node), and the vagus nerve provides parasympathetic input to the heart by releasing acetylcholine onto sinoatrial node cells. Therefore, stimulation of the accelerans nerve increases heart rate, while stimulation of the vagus nerve decreases it.[5]

Due to individuals having a constant blood volume, one of the physiological ways to deliver more oxygen to an organ is to increase heart rate to permit blood to pass by the organ more often.[4] Normal resting heart rates range from 60-100 bpm.[6][7][8][9] Bradycardia is defined as a resting heart rate below 60 bpm. However, heart rates from 50 to 60 bpm are common among healthy people and do not necessarily require special attention.[2] Tachycardia is defined as a resting heart rate above 100 bpm, though persistent rest rates between 80–100 bpm, mainly if they are present during sleep, may be signs of hyperthyroidism or anemia (see below).[4]

- Central nervous system stimulants such as substituted amphetamines increase heart rate.

- Central nervous system depressants or sedatives decrease the heart rate (apart from some particularly strange ones with equally strange effects, such as ketamine which can cause – amongst many other things – stimulant-like effects such as tachycardia).

There are many ways in which the heart rate speeds up or slows down. Most involve stimulant-like endorphins and hormones being released in the brain, many of which are those that are 'forced'/'enticed' out by the ingestion and processing of drugs.

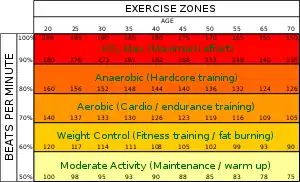

This section discusses target heart rates for healthy persons, which would be inappropriately high for most persons with coronary artery disease.[10]

Cardiovascular centres

The heart rate is rhythmically generated by the sinoatrial node. It is also influenced by central factors through sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves.[11] Nervous influence over the heart rate is centralized within the two paired cardiovascular centres of the medulla oblongata. The cardioaccelerator regions stimulate activity via sympathetic stimulation of the cardioaccelerator nerves, and the cardioinhibitory centers decrease heart activity via parasympathetic stimulation as one component of the vagus nerve. During rest, both centers provide slight stimulation to the heart, contributing to autonomic tone. This is a similar concept to tone in skeletal muscles. Normally, vagal stimulation predominates as, left unregulated, the SA node would initiate a sinus rhythm of approximately 100 bpm.[12]

Both sympathetic and parasympathetic stimuli flow through the paired cardiac plexus near the base of the heart. The cardioaccelerator center also sends additional fibers, forming the cardiac nerves via sympathetic ganglia (the cervical ganglia plus superior thoracic ganglia T1–T4) to both the SA and AV nodes, plus additional fibers to the atria and ventricles. The ventricles are more richly innervated by sympathetic fibers than parasympathetic fibers. Sympathetic stimulation causes the release of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine (also known as noradrenaline) at the neuromuscular junction of the cardiac nerves. This shortens the repolarization period, thus speeding the rate of depolarization and contraction, which results in an increased heartrate. It opens chemical or ligand-gated sodium and calcium ion channels, allowing an influx of positively charged ions.[12]

Norepinephrine binds to the beta–1 receptor. High blood pressure medications are used to block these receptors and so reduce the heart rate.[12]

Parasympathetic stimulation originates from the cardioinhibitory region of the brain[13] with impulses traveling via the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X). The vagus nerve sends branches to both the SA and AV nodes, and to portions of both the atria and ventricles. Parasympathetic stimulation releases the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) at the neuromuscular junction. ACh slows HR by opening chemical- or ligand-gated potassium ion channels to slow the rate of spontaneous depolarization, which extends repolarization and increases the time before the next spontaneous depolarization occurs. Without any nervous stimulation, the SA node would establish a sinus rhythm of approximately 100 bpm. Since resting rates are considerably less than this, it becomes evident that parasympathetic stimulation normally slows HR. This is similar to an individual driving a car with one foot on the brake pedal. To speed up, one need merely remove one's foot from the brake and let the engine increase speed. In the case of the heart, decreasing parasympathetic stimulation decreases the release of ACh, which allows HR to increase up to approximately 100 bpm. Any increases beyond this rate would require sympathetic stimulation.[12]

Input to the cardiovascular centres

The cardiovascular centres receive input from a series of visceral receptors with impulses traveling through visceral sensory fibers within the vagus and sympathetic nerves via the cardiac plexus. Among these receptors are various proprioreceptors, baroreceptors, and chemoreceptors, plus stimuli from the limbic system which normally enable the precise regulation of heart function, via cardiac reflexes. Increased physical activity results in increased rates of firing by various proprioreceptors located in muscles, joint capsules, and tendons. The cardiovascular centres monitor these increased rates of firing, suppressing parasympathetic stimulation or increasing sympathetic stimulation as needed in order to increase blood flow.[12]

Similarly, baroreceptors are stretch receptors located in the aortic sinus, carotid bodies, the venae cavae, and other locations, including pulmonary vessels and the right side of the heart itself. Rates of firing from the baroreceptors represent blood pressure, level of physical activity, and the relative distribution of blood. The cardiac centers monitor baroreceptor firing to maintain cardiac homeostasis, a mechanism called the baroreceptor reflex. With increased pressure and stretch, the rate of baroreceptor firing increases, and the cardiac centers decrease sympathetic stimulation and increase parasympathetic stimulation. As pressure and stretch decrease, the rate of baroreceptor firing decreases, and the cardiac centers increase sympathetic stimulation and decrease parasympathetic stimulation.[12]

There is a similar reflex, called the atrial reflex or Bainbridge reflex, associated with varying rates of blood flow to the atria. Increased venous return stretches the walls of the atria where specialized baroreceptors are located. However, as the atrial baroreceptors increase their rate of firing and as they stretch due to the increased blood pressure, the cardiac center responds by increasing sympathetic stimulation and inhibiting parasympathetic stimulation to increase HR. The opposite is also true.[12]

Increased metabolic byproducts associated with increased activity, such as carbon dioxide, hydrogen ions, and lactic acid, plus falling oxygen levels, are detected by a suite of chemoreceptors innervated by the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves. These chemoreceptors provide feedback to the cardiovascular centers about the need for increased or decreased blood flow, based on the relative levels of these substances.[12]

The limbic system can also significantly impact HR related to emotional state. During periods of stress, it is not unusual to identify higher than normal HRs, often accompanied by a surge in the stress hormone cortisol. Individuals experiencing extreme anxiety may manifest panic attacks with symptoms that resemble those of heart attacks. These events are typically transient and treatable. Meditation techniques have been developed to ease anxiety and have been shown to lower HR effectively. Doing simple deep and slow breathing exercises with one's eyes closed can also significantly reduce this anxiety and HR.[12]

Factors influencing heart rate

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Using a combination of autorhythmicity and innervation, the cardiovascular center is able to provide relatively precise control over the heart rate, but other factors can impact on this. These include hormones, notably epinephrine, norepinephrine, and thyroid hormones; levels of various ions including calcium, potassium, and sodium; body temperature; hypoxia; and pH balance.[12]

Epinephrine and norepinephrine

The catecholamines, epinephrine and norepinephrine, secreted by the adrenal medulla form one component of the extended fight-or-flight mechanism. The other component is sympathetic stimulation. Epinephrine and norepinephrine have similar effects: binding to the beta-1 adrenergic receptors, and opening sodium and calcium ion chemical- or ligand-gated channels. The rate of depolarization is increased by this additional influx of positively charged ions, so the threshold is reached more quickly and the period of repolarization is shortened. However, massive releases of these hormones coupled with sympathetic stimulation may actually lead to arrhythmias. There is no parasympathetic stimulation to the adrenal medulla.[12]

Thyroid hormones

In general, increased levels of the thyroid hormones (thyroxine(T4) and triiodothyronine (T3)), increase the heart rate; excessive levels can trigger tachycardia. The impact of thyroid hormones is typically of a much longer duration than that of the catecholamines. The physiologically active form of triiodothyronine, has been shown to directly enter cardiomyocytes and alter activity at the level of the genome. It also impacts the beta adrenergic response similar to epinephrine and norepinephrine.[12]

Calcium

Calcium ion levels have a great impact on heart rate and contractility: increased calcium levels cause an increase in both. High levels of calcium ions result in hypercalcemia and excessive levels can induce cardiac arrest. Drugs known as calcium channel blockers slow HR by binding to these channels and blocking or slowing the inward movement of calcium ions.[12]

Caffeine and nicotine

Caffeine and nicotine are both stimulants of the nervous system and of the cardiac centres causing an increased heart rate. Caffeine works by increasing the rates of depolarization at the SA node, whereas nicotine stimulates the activity of the sympathetic neurons that deliver impulses to the heart.[12] Both stimulants are legal and unregulated, and nicotine is very addictive.[12]

Effects of stress

Both surprise and stress induce physiological response: elevate heart rate substantially.[14] In a study conducted on 8 female and male student actors ages 18 to 25, their reaction to an unforeseen occurrence (the cause of stress) during a performance was observed in terms of heart rate. In the data collected, there was a noticeable trend between the location of actors (onstage and offstage) and their elevation in heart rate in response to stress; the actors present offstage reacted to the stressor immediately, demonstrated by their immediate elevation in heart rate the minute the unexpected event occurred, but the actors present onstage at the time of the stressor reacted in the following 5 minute period (demonstrated by their increasingly elevated heart rate). This trend regarding stress and heart rate is supported by previous studies; negative emotion/stimulus has a prolonged effect on heart rate in individuals who are directly impacted.[15] In regard to the characters present onstage, a reduced startle response has been associated with a passive defense, and the diminished initial heart rate response has been predicted to have a greater tendency to dissociation.[16] Further, note that heart rate is an accurate measure of stress and the startle response which can be easily observed to determine the effects of certain stressors.

Factors decreasing heart rate

The heart rate can be slowed by altered sodium and potassium levels, hypoxia, acidosis, alkalosis, and hypothermia. The relationship between electrolytes and HR is complex, but maintaining electrolyte balance is critical to the normal wave of depolarization. Of the two ions, potassium has the greater clinical significance. Initially, both hyponatremia (low sodium levels) and hypernatremia (high sodium levels) may lead to tachycardia. Severely high hypernatremia may lead to fibrillation, which may cause CO to cease. Severe hyponatremia leads to both bradycardia and other arrhythmias. Hypokalemia (low potassium levels) also leads to arrhythmias, whereas hyperkalemia (high potassium levels) causes the heart to become weak and flaccid, and ultimately to fail.[12]

Heart muscle relies exclusively on aerobic metabolism for energy. Severe (an insufficient supply of oxygen) leads to decreasing HRs, since metabolic reactions fueling heart contraction are restricted.[12]

Acidosis is a condition in which excess hydrogen ions are present, and the patient's blood expresses a low pH value. Alkalosis is a condition in which there are too few hydrogen ions, and the patient's blood has an elevated pH. Normal blood pH falls in the range of 7.35–7.45, so a number lower than this range represents acidosis and a higher number represents alkalosis. Enzymes, being the regulators or catalysts of virtually all biochemical reactions - are sensitive to pH and will change shape slightly with values outside their normal range. These variations in pH and accompanying slight physical changes to the active site on the enzyme decrease the rate of formation of the enzyme-substrate complex, subsequently decreasing the rate of many enzymatic reactions, which can have complex effects on HR. Severe changes in pH will lead to denaturation of the enzyme.[12]

The last variable is body temperature. Elevated body temperature is called hyperthermia, and suppressed body temperature is called hypothermia. Slight hyperthermia results in increasing HR and strength of contraction. Hypothermia slows the rate and strength of heart contractions. This distinct slowing of the heart is one component of the larger diving reflex that diverts blood to essential organs while submerged. If sufficiently chilled, the heart will stop beating, a technique that may be employed during open heart surgery. In this case, the patient's blood is normally diverted to an artificial heart-lung machine to maintain the body's blood supply and gas exchange until the surgery is complete, and sinus rhythm can be restored. Excessive hyperthermia and hypothermia will both result in death, as enzymes drive the body systems to cease normal function, beginning with the central nervous system.[12]

Physiological control over heart rate

_%E2%80%93_examples_of_instantaneous_heart_rate_(ifH)_responses.jpg.webp)

A study shows that bottlenose dolphins can learn – apparently via instrumental conditioning – to rapidly and selectively slow down their heart rate during diving for conserving oxygen depending on external signals. In humans regulating heart rate by methods such as listening to music, meditation or a vagal maneuver takes longer and only lowers the rate to a much smaller extent.[17][18]

In different circumstances

Heart rate is not a stable value and it increases or decreases in response to the body's need in a way to maintain an equilibrium (basal metabolic rate) between requirement and delivery of oxygen and nutrients. The normal SA node firing rate is affected by autonomic nervous system activity: sympathetic stimulation increases and parasympathetic stimulation decreases the firing rate.[19] A number of different metrics are used to describe heart rate.

Resting heart rate

Normal pulse rates at rest, in beats per minute (BPM):[20]

| newborn (0–1 months old) |

infants (1 – 11 months) |

children (1 – 2 years old) |

children (3 – 4 years) |

children (5 – 6 years) |

children (7 – 9 years) |

children over 10 years & adults, including seniors |

well-trained adult athletes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70-190 | 80–160 | 80-130 | 80-120 | 75–115 | 70–110 | 60–100 | 40–60 |

The basal or resting heart rate (HRrest) is defined as the heart rate when a person is awake, in a neutrally temperate environment, and has not been subject to any recent exertion or stimulation, such as stress or surprise. The available evidence indicates that the normal range for resting heart rate is 50-90 beats per minute.[6][7][8][9] This resting heart rate is often correlated with mortality. For example, all-cause mortality is increased by 1.22 (hazard ratio) when heart rate exceeds 90 beats per minute.[6] The mortality rate of patients with myocardial infarction increased from 15% to 41% if their admission heart rate was greater than 90 beats per minute.[7] ECG of 46,129 individuals with low risk for cardiovascular disease revealed that 96% had resting heart rates ranging from 48 to 98 beats per minute.[8] Finally, in one study 98% of cardiologists suggested that as a desirable target range, 50 to 90 beats per minute is more appropriate than 60 to 100.[9] The normal resting heart rate is based on the at-rest firing rate of the heart's sinoatrial node, where the faster pacemaker cells driving the self-generated rhythmic firing and responsible for the heart's autorhythmicity are located.[21] For endurance athletes at the elite level, it is not unusual to have a resting heart rate between 33 and 50 bpm.

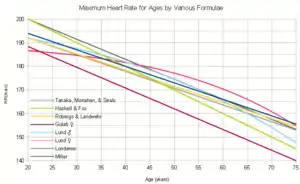

Maximum heart rate

The maximum heart rate (HRmax) is the highest heart rate an individual can achieve without severe problems through exercise stress,[22][23] and generally decreases with age. Since HRmax varies by individual, the most accurate way of measuring any single person's HRmax is via a cardiac stress test. In this test, a person is subjected to controlled physiologic stress (generally by treadmill) while being monitored by an ECG. The intensity of exercise is periodically increased until certain changes in heart function are detected on the ECG monitor, at which point the subject is directed to stop. Typical duration of the test ranges ten to twenty minutes.

Adults who are beginning a new exercise regimen are often advised to perform this test only in the presence of medical staff due to risks associated with high heart rates. For general purposes, a formula is often employed to estimate a person's maximum heart rate. However, these predictive formulas have been criticized as inaccurate because they generalized population-averages and usually focus on a person's age and do not even take normal resting pulse rate into consideration. It is well-established that there is a "poor relationship between maximal heart rate and age" and large standard deviations relative to predicted heart rates.[24] (see Limitations of Estimation Formulas).

A number of formulas are used to estimate HRmax

Nes, et al.

Based on measurements of 3320 healthy men and women aged between 19 and 89, and including the potential modifying effect of gender, body composition, and physical activity, Nes et al found

- HRmax = 211 − (0.64 × age)

This relationship was found to hold the substantially regardless of gender, physical activity status, maximal oxygen uptake, smoking, or body mass index. However, a standard error of the estimate of 10.8 beats/min must be accounted for when applying the formula to clinical settings, and the researchers concluded that actual measurement via a maximal test may be preferable whenever possible.[25]

Tanaka, Monahan, & Seals

From Tanaka, Monahan, & Seals (2001):

- HRmax = 208 − (0.7 × age) [26]

Their meta-analysis (of 351 prior studies involving 492 groups and 18,712 subjects) and laboratory study (of 514 healthy subjects) concluded that, using this equation, HRmax was very strongly correlated to age (r = −0.90). The regression equation that was obtained in the laboratory-based study (209 − 0.7 x age), was virtually identical to that of the meta-study. The results showed HRmax to be independent of gender and independent of wide variations in habitual physical activity levels. This study found a standard deviation of ~10 beats per minute for individuals of any age, meaning the HRmax formula given has an accuracy of ±20 beats per minute.[26]

Oakland University

In 2007, researchers at the Oakland University analyzed maximum heart rates of 132 individuals recorded yearly over 25 years, and produced a linear equation very similar to the Tanaka formula, HRmax = 207 − (0.7 × age), and a nonlinear equation, HRmax = 192 − (0.007 × age2). The linear equation had a confidence interval of ±5–8 bpm and the nonlinear equation had a tighter range of ±2–5 bpm [27]

Haskell & Fox

Notwithstanding the research of Tanaka, Monahan, & Seals, the most widely cited formula for HRmax (which contains no reference to any standard deviation) is still:

- HRmax = 220 − age

Although attributed to various sources, it is widely thought to have been devised in 1970 by Dr. William Haskell and Dr. Samuel Fox.[28] Inquiry into the history of this formula reveals that it was not developed from original research, but resulted from observation based on data from approximately 11 references consisting of published research or unpublished scientific compilations.[29] It gained widespread use through being used by Polar Electro in its heart rate monitors,[28] which Dr. Haskell has "laughed about",[28] as the formula "was never supposed to be an absolute guide to rule people's training."[28]

While it is the most common (and easy to remember and calculate), this particular formula is not considered by reputable health and fitness professionals to be a good predictor of HRmax. Despite the widespread publication of this formula, research spanning two decades reveals its large inherent error, Sxy = 7–11 bpm. Consequently, the estimation calculated by HRmax = 220 − age has neither the accuracy nor the scientific merit for use in exercise physiology and related fields.[29]

Robergs & Landwehr

A 2002 study[29] of 43 different formulas for HRmax (including that of Haskell and Fox – see above) published in the Journal of Exercise Psychology concluded that:

- no "acceptable" formula currently existed (they used the term "acceptable" to mean acceptable for both prediction of VO2, and prescription of exercise training HR ranges)

- the least objectionable formula (Inbar, et al., 1994) was:

- HRmax = 205.8 − (0.685 × age) [30]

- This had a standard deviation that, although large (6.4 bpm), was considered acceptable for prescribing exercise training HR ranges.

Gulati (for women)

Research conducted at Northwestern University by Martha Gulati, et al., in 2010[31] suggested a maximum heart rate formula for women:

- HRmax = 206 − (0.88 × age)

Wohlfart, B. and Farazdaghi, G.R.

A 2003 study from Lund, Sweden gives reference values (obtained during bicycle ergometry) for men:

- HRmax = 203.7 / ( 1 + exp( 0.033 × (age − 104.3) ) ) [32]

and for women:

- HRmax = 190.2 / ( 1 + exp( 0.0453 × (age − 107.5) ) ) [33]

Other formulae

- HRmax = 206.3 − (0.711 × age)

- (Often attributed to "Londeree and Moeschberger from the University of Missouri")

- HRmax = 217 − (0.85 × age)

- (Often attributed to "Miller et al. from Indiana University")

Limitations

Maximum heart rates vary significantly between individuals.[28] Even within a single elite sports team, such as Olympic rowers in their 20s, maximum heart rates have been reported as varying from 160 to 220.[28] Such a variation would equate to a 60 or 90 year age gap in the linear equations above, and would seem to indicate the extreme variation about these average figures.

Figures are generally considered averages, and depend greatly on individual physiology and fitness. For example, an endurance runner's rates will typically be lower due to the increased size of the heart required to support the exercise, while a sprinter's rates will be higher due to the improved response time and short duration. While each may have predicted heart rates of 180 (= 220 − age), these two people could have actual HRmax 20 beats apart (e.g., 170–190).

Further, note that individuals of the same age, the same training, in the same sport, on the same team, can have actual HRmax 60 bpm apart (160–220):[28] the range is extremely broad, and some say "The heart rate is probably the least important variable in comparing athletes."[28]

Heart rate reserve

Heart rate reserve (HRreserve) is the difference between a person's measured or predicted maximum heart rate and resting heart rate. Some methods of measurement of exercise intensity measure percentage of heart rate reserve. Additionally, as a person increases their cardiovascular fitness, their HRrest will drop, and the heart rate reserve will increase. Percentage of HRreserve is equivalent to percentage of VO2 reserve.[34]

- HRreserve = HRmax − HRrest

This is often used to gauge exercise intensity (first used in 1957 by Karvonen).[35]

Karvonen's study findings have been questioned, due to the following:

- The study did not use VO2 data to develop the equation.

- Only six subjects were used, and the correlation between the percentages of HRreserve and VO2 max was not statistically significant.[36]

Target heart rate

For healthy people, the Target Heart Rate (THR) or Training Heart Rate Range (THRR) is a desired range of heart rate reached during aerobic exercise which enables one's heart and lungs to receive the most benefit from a workout. This theoretical range varies based mostly on age; however, a person's physical condition, sex, and previous training also are used in the calculation. Below are two ways to calculate one's THR. In each of these methods, there is an element called "intensity" which is expressed as a percentage. The THR can be calculated as a range of 65–85% intensity. However, it is crucial to derive an accurate HRmax to ensure these calculations are meaningful.

Example for someone with a HRmax of 180 (age 40, estimating HRmax As 220 − age):

- 65% Intensity: (220 − (age = 40)) × 0.65 → 117 bpm

- 85% Intensity: (220 − (age = 40)) × 0.85 → 154bpm

Karvonen method

The Karvonen method factors in resting heart rate (HRrest) to calculate target heart rate (THR), using a range of 50–85% intensity:[37]

- THR = ((HRmax − HRrest) × % intensity) + HRrest

Equivalently,

- THR = (HRreserve × % intensity) + HRrest

Example for someone with a HRmax of 180 and a HRrest of 70 (and therefore a HRreserve of 110):

- 50% Intensity: ((180 − 70) × 0.50) + 70 = 125 bpm

- 85% Intensity: ((180 − 70) × 0.85) + 70 = 163 bpm

Zoladz method

An alternative to the Karvonen method is the Zoladz method, which is used to test an athlete's capabilities at specific heart rates. These are not intended to be used as exercise zones, although they are often used as such.[38] The Zoladz test zones are derived by subtracting values from HRmax:

- THR = HRmax − Adjuster ± 5 bpm

- Zone 1 Adjuster = 50 bpm

- Zone 2 Adjuster = 40 bpm

- Zone 3 Adjuster = 30 bpm

- Zone 4 Adjuster = 20 bpm

- Zone 5 Adjuster = 10 bpm

Example for someone with a HRmax of 180:

- Zone 1(easy exercise): 180 − 50 ± 5 → 125 − 135 bpm

- Zone 4(tough exercise): 180 − 20 ± 5 → 155 − 165 bpm

Heart rate recovery

Heart rate recovery (HRrecovery) is the reduction in heart rate at peak exercise and the rate as measured after a cool-down period of fixed duration.[39] A greater reduction in heart rate after exercise during the reference period is associated with a higher level of cardiac fitness.[40]

Heart rates that do not drop by more than 12 bpm one minute after stopping exercise are associated with an increased risk of death.[39] Investigators of the Lipid Research Clinics Prevalence Study, which included 5,000 subjects, found that patients with an abnormal HRrecovery (defined as a decrease of 42 beats per minutes or less at two minutes post-exercise) had a mortality rate 2.5 times greater than patients with a normal recovery.[40] Another study by Nishime et al. and featuring 9,454 patients followed for a median period of 5.2 years found a four-fold increase in mortality in subjects with an abnormal HRrecovery (≤12 bpm reduction one minute after the cessation of exercise).[40] Shetler et al. studied 2,193 patients for thirteen years and found that a HRrecovery of ≤22 bpm after two minutes "best identified high-risk patients".[40] They also found that while HRrecovery had significant prognostic value it had no diagnostic value.[40][41]

Development

The human heart beats more than 3.5 billion times in an average lifetime.

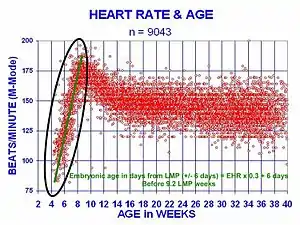

The heartbeat of a human embryo begins at approximately 21 days after conception, or five weeks after the last normal menstrual period (LMP), which is the date normally used to date pregnancy in the medical community. The electrical depolarizations that trigger cardiac myocytes to contract arise spontaneously within the myocyte itself. The heartbeat is initiated in the pacemaker regions and spreads to the rest of the heart through a conduction pathway. Pacemaker cells develop in the primitive atrium and the sinus venosus to form the sinoatrial node and the atrioventricular node respectively. Conductive cells develop the bundle of His and carry the depolarization into the lower heart.

The human heart begins beating at a rate near the mother's, about 75–80 beats per minute (bpm). The embryonic heart rate then accelerates linearly for the first month of beating, peaking at 165–185 bpm during the early 7th week, (early 9th week after the LMP). This acceleration is approximately 3.3 bpm per day, or about 10 bpm every three days, an increase of 100 bpm in the first month.[42]

After peaking at about 9.2 weeks after the LMP, it decelerates to about 150 bpm (+/-25 bpm) during the 15th week after the LMP. After the 15th week the deceleration slows reaching an average rate of about 145 (+/-25 bpm) bpm at term. The regression formula which describes this acceleration before the embryo reaches 25 mm in crown-rump length or 9.2 LMP weeks is:

There is no difference in male and female heart rates before birth.[43]

Clinical significance

Manual measurement

Heart rate is measured by finding the pulse of the heart. This pulse rate can be found at any point on the body where the artery's pulsation is transmitted to the surface by pressuring it with the index and middle fingers; often it is compressed against an underlying structure like bone. The thumb should not be used for measuring another person's heart rate, as its strong pulse may interfere with the correct perception of the target pulse.

The radial artery is the easiest to use to check the heart rate. However, in emergency situations the most reliable arteries to measure heart rate are carotid arteries. This is important mainly in patients with atrial fibrillation, in whom heart beats are irregular and stroke volume is largely different from one beat to another. In those beats following a shorter diastolic interval left ventricle does not fill properly, stroke volume is lower and pulse wave is not strong enough to be detected by palpation on a distal artery like the radial artery. It can be detected, however, by doppler.[44][45]

Possible points for measuring the heart rate are:

- The ventral aspect of the wrist on the side of the thumb (radial artery).

- The ulnar artery.

- The inside of the elbow, or under the biceps muscle (brachial artery).

- The groin (femoral artery).

- Behind the medial malleolus on the feet (posterior tibial artery).

- Middle of dorsum of the foot (dorsalis pedis).

- Behind the knee (popliteal artery).

- Over the abdomen (abdominal aorta).

- The chest (apex of the heart), which can be felt with one's hand or fingers. It is also possible to auscultate the heart using a stethoscope.

- In the neck, lateral of the larynx (carotid artery)

- The temple (superficial temporal artery).

- The lateral edge of the mandible (facial artery).

- The side of the head near the ear (posterior auricular artery).

Electronic measurement

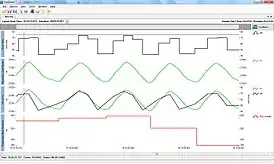

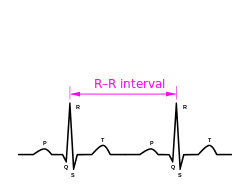

A more precise method of determining heart rate involves the use of an electrocardiograph, or ECG (also abbreviated EKG). An ECG generates a pattern based on electrical activity of the heart, which closely follows heart function. Continuous ECG monitoring is routinely done in many clinical settings, especially in critical care medicine. On the ECG, instantaneous heart rate is calculated using the R wave-to-R wave (RR) interval and multiplying/dividing in order to derive heart rate in heartbeats/min. Multiple methods exist:

- HR = 1000*60/(RR interval in milliseconds)

- HR = 60/(RR interval in seconds)

- HR = 300/number of "large" squares between successive R waves.

- HR= 1,500 number of large blocks

Heart rate monitors allow measurements to be taken continuously and can be used during exercise when manual measurement would be difficult or impossible (such as when the hands are being used). Various commercial heart rate monitors are also available. Some monitors, used during sport, consist of a chest strap with electrodes. The signal is transmitted to a wrist receiver for display.

Alternative methods of measurement include seismocardiography.[46]

Optical measurements

Pulse oximetry of the finger and laser Doppler imaging of the eye fundus are often used in the clinics. Those techniques can assess the heart rate by measuring the delay between pulses.

Tachycardia

Tachycardia is a resting heart rate more than 100 beats per minute. This number can vary as smaller people and children have faster heart rates than average adults.

Physiological conditions where tachycardia occurs:

- Pregnancy

- Emotional conditions such as anxiety or stress.

- Exercise

Pathological conditions where tachycardia occurs:

- Sepsis

- Fever

- Anemia

- Hypoxia

- Hyperthyroidism

- Hypersecretion of catecholamines

- Cardiomyopathy

- Valvular heart diseases

- Acute Radiation Syndrome

Bradycardia

Bradycardia was defined as a heart rate less than 60 beats per minute when textbooks asserted that the normal range for heart rates was 60–100 bpm. The normal range has since been revised in textbooks to 50–90 bpm for a human at total rest. Setting a lower threshold for bradycardia prevents misclassification of fit individuals as having a pathologic heart rate. The normal heart rate number can vary as children and adolescents tend to have faster heart rates than average adults. Bradycardia may be associated with medical conditions such as hypothyroidism.

Trained athletes tend to have slow resting heart rates, and resting bradycardia in athletes should not be considered abnormal if the individual has no symptoms associated with it. For example, Miguel Indurain, a Spanish cyclist and five time Tour de France winner, had a resting heart rate of 28 beats per minute,[48] one of the lowest ever recorded in a healthy human. Daniel Green achieved the world record for the slowest heartbeat in a healthy human with a heart rate of just 26 bpm in 2014.[49]

Arrhythmia

Arrhythmias are abnormalities of the heart rate and rhythm (sometimes felt as palpitations). They can be divided into two broad categories: fast and slow heart rates. Some cause few or minimal symptoms. Others produce more serious symptoms of lightheadedness, dizziness and fainting.

Correlation with cardiovascular mortality risk

A number of investigations indicate that faster resting heart rate has emerged as a new risk factor for mortality in homeothermic mammals, particularly cardiovascular mortality in human beings. Faster heart rate may accompany increased production of inflammation molecules and increased production of reactive oxygen species in cardiovascular system, in addition to increased mechanical stress to the heart. There is a correlation between increased resting rate and cardiovascular risk. This is not seen to be "using an allotment of heart beats" but rather an increased risk to the system from the increased rate.[1]

An Australian-led international study of patients with cardiovascular disease has shown that heart beat rate is a key indicator for the risk of heart attack. The study, published in The Lancet (September 2008) studied 11,000 people, across 33 countries, who were being treated for heart problems. Those patients whose heart rate was above 70 beats per minute had significantly higher incidence of heart attacks, hospital admissions and the need for surgery. Higher heart rate is thought to be correlated with an increase in heart attack and about a 46 percent increase in hospitalizations for non-fatal or fatal heart attack.[50]

Other studies have shown that a high resting heart rate is associated with an increase in cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in the general population and in patients with chronic diseases.[51][52] A faster resting heart rate is associated with shorter life expectancy [1][53] and is considered a strong risk factor for heart disease and heart failure,[54] independent of level of physical fitness.[55] Specifically, a resting heart rate above 65 beats per minute has been shown to have a strong independent effect on premature mortality; every 10 beats per minute increase in resting heart rate has been shown to be associated with a 10–20% increase in risk of death.[56] In one study, men with no evidence of heart disease and a resting heart rate of more than 90 beats per minute had a five times higher risk of sudden cardiac death.[54] Similarly, another study found that men with resting heart rates of over 90 beats per minute had an almost two-fold increase in risk for cardiovascular disease mortality; in women it was associated with a three-fold increase.[53]

Given these data, heart rate should be considered in the assessment of cardiovascular risk, even in apparently healthy individuals.[57] Heart rate has many advantages as a clinical parameter: It is inexpensive and quick to measure and is easily understandable.[58] Although the accepted limits of heart rate are between 60 and 100 beats per minute, this was based for convenience on the scale of the squares on electrocardiogram paper; a better definition of normal sinus heart rate may be between 50 and 90 beats per minute.[59][51]

Standard textbooks of physiology and medicine mention that heart rate (HR) is readily calculated from the ECG as follows: HR = 1000*60/RR interval in milliseconds, HR = 60/RR interval in seconds, or HR = 300/number of large squares between successive R waves. In each case, the authors are actually referring to instantaneous HR, which is the number of times the heart would beat if successive RR intervals were constant.

Lifestyle and pharmacological regimens may be beneficial to those with high resting heart rates.[56] Exercise is one possible measure to take when an individual's heart rate is higher than 80 beats per minute.[58][60] Diet has also been found to be beneficial in lowering resting heart rate: In studies of resting heart rate and risk of death and cardiac complications on patients with type 2 diabetes, legumes were found to lower resting heart rate.[61] This is thought to occur because in addition to the direct beneficial effects of legumes, they also displace animal proteins in the diet, which are higher in saturated fat and cholesterol.[61] Another nutrient is omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (omega-3 fatty acid or LC-PUFA). In a meta-analysis with a total of 51 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involvingy 3,000 participants, the supplement mildly but significantly reduced heart rate (-2.23 bpm; 95% CI: -3.07, -1.40 bpm). When docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) were compared, modest heart rate reduction was observed in trials that supplemented with DHA (-2.47 bpm; 95% CI: -3.47, -1.46 bpm), but not in those received EPA.[62]

A very slow heart rate (bradycardia) may be associated with heart block.[63] It may also arise from autonomous nervous system impairment.

Notes

- Zhang GQ, Zhang W (2009). "Heart rate, lifespan, and mortality risk". Ageing Research Reviews. 8 (1): 52–60. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2008.10.001. PMID 19022405. S2CID 23482241.

- "All About Heart Rate (Pulse)". All About Heart Rate (Pulse). American Heart Association. 22 Aug 2017. Retrieved 25 Jan 2018.

- "Tachycardia| Fast Heart Rate". Tachycardia. American Heart Association. 2 May 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- Fuster, Wayne & O'Rouke 2001, pp. 78–79.

- Schmidt-Nielsen, Knut (1997). Animal physiology: adaptation and environment (5th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-521-57098-5.

- Aladin, Amer I.; Whelton, Seamus P.; Al-Mallah, Mouaz H.; Blaha, Michael J.; Keteyian, Steven J.; Juraschek, Stephen P.; Rubin, Jonathan; Brawner, Clinton A.; Michos, Erin D. (2014-12-01). "Relation of resting heart rate to risk for all-cause mortality by gender after considering exercise capacity (the Henry Ford exercise testing project)". The American Journal of Cardiology. 114 (11): 1701–06. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.08.042. ISSN 1879-1913. PMID 25439450.

- Hjalmarson, A.; Gilpin, E. A.; Kjekshus, J.; Schieman, G.; Nicod, P.; Henning, H.; Ross, J. (1990-03-01). "Influence of heart rate on mortality after acute myocardial infarction". The American Journal of Cardiology. 65 (9): 547–53. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(90)91029-6. ISSN 0002-9149. PMID 1968702.

- Mason, Jay W.; Ramseth, Douglas J.; Chanter, Dennis O.; Moon, Thomas E.; Goodman, Daniel B.; Mendzelevski, Boaz (2007-07-01). "Electrocardiographic reference ranges derived from 79,743 ambulatory subjects". Journal of Electrocardiology. 40 (3): 228–34. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2006.09.003. ISSN 1532-8430. PMID 17276451.

- Spodick, D. H. (1993-08-15). "Survey of selected cardiologists for an operational definition of normal sinus heart rate". The American Journal of Cardiology. 72 (5): 487–88. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(93)91153-9. ISSN 0002-9149. PMID 8352202.

- Anderson JM (1991). "Rehabilitating elderly cardiac patients". West. J. Med. 154 (5): 573–78. PMC 1002834. PMID 1866953.

- Hall, Arthur C. Guyton, John E. (2005). Textbook of medical physiology (11th ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 116–22. ISBN 978-0-7216-0240-0.

- Betts, J. Gordon (2013). Anatomy & physiology. pp. 787–846. ISBN 978-1938168130. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- Garcia A, Marquez MF, Fierro EF, Baez JJ, Rockbrand LP, Gomez-Flores J (May 2020). "Cardioinhibitory syncope: from pathophysiology to treatment-should we think on cardioneuroablation?". J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 59 (2): 441–461. doi:10.1007/s10840-020-00758-2. PMID 32377918. S2CID 218527702.

- Mustonen, Veera; Pantzar, Mika (2013). "Tracking social rhythms of the heart". Approaching Religion. 3 (2): 16–21. doi:10.30664/ar.67512.

- Brosschot, J.F.; Thayer, J.F. (2003). "Heart rate response is longer after negative emotions than after positive emotions". International Journal of Psychophysiology. 50 (3): 181–87. doi:10.1016/s0167-8760(03)00146-6. PMID 14585487.

- Chou, C.Y.; Marca, R.L.; Steptoe, A.; Brewin, C.R. (2014). "Heart rate, startle response, and intrusive trauma memories". Psychophysiology. 51 (3): 236–46. doi:10.1111/psyp.12176. PMC 4283725. PMID 24397333.

- "Dolphins conserve oxygen and prevent dive-related problems by consciously decreasing their heart rates before diving". phys.org. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- Fahlman, Andreas; Cozzi, Bruno; Manley, Mercy; Jabas, Sandra; Malik, Marek; Blawas, Ashley; Janik, Vincent M. (2020). "Conditioned Variation in Heart Rate During Static Breath-Holds in the Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus)". Frontiers in Physiology. 11. doi:10.3389/fphys.2020.604018. ISSN 1664-042X. S2CID 227128277. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

Available under CC BY 4.0.

Available under CC BY 4.0. - Sherwood, L. (2008). Human Physiology, From Cells to Systems. p. 327. ISBN 9780495391845. Retrieved 2013-03-10.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services - National Ites of Health Pulse

- Berne, Robert; Levy, Matthew; Koeppen, Bruce; Stanton, Bruce (2004). Physiology. Elsevier Mosby. p. 276. ISBN 978-0-8243-0348-8.

- "HRmax (Fitness)". MiMi.

- Atwal S, Porter J, MacDonald P (February 2002). "Cardiovascular effects of strenuous exercise in adult recreational hockey: the Hockey Heart Study". CMAJ. 166 (3): 303–07. PMC 99308. PMID 11868637.

- Froelicher, Victor; Myers, Jonathan (2006). Exercise and the Heart (fifth ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. ix, 108–12. ISBN 978-1-4160-0311-3.

- Nes, B.M.; Janszky, I.; Wisloff, U.; Stoylen, A.; Karlsen, T. (December 2013). "Age‐predicted maximal heart rate in healthy subjects: The HUNT Fitness Study". Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 23 (6): 697–704. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2012.01445.x. PMID 22376273. S2CID 2380139.

- Tanaka H, Monahan KD, Seals DR (January 2001). "Age-predicted maximal heart rate revisited". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 37 (1): 153–56. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(00)01054-8. PMID 11153730.

- "Longitudinal Modeling of the Relationship between Age and Maximal Heart Rate", GELLISH, RONALD L.; GOSLIN, BRIAN R.; OLSON, RONALD E.; McDONALD, AUDRY; RUSSI, GARY D.; MOUDGIL, VIRINDER K. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise: May 2007 - Volume 39 - Issue 5 - p 822-829 doi: 10.1097/mss.0b013e31803349c6 https://journals.lww.com/acsm-msse/Fulltext/2007/05000/Longitudinal_Modeling_of_the_Relationship_between.11.aspx

- Kolata, Gina (2001-04-24). "'Maximum' Heart Rate Theory Is Challenged". New York Times.

- Robergs R, Landwehr R (2002). "The Surprising History of the 'HRmax=220-age' Equation" (PDF). Journal of Exercise Physiology. 5 (2): 1–10.

- Inbar O., Oten A., Scheinowitz M., Rotstein A., Dlin R., Casaburi R. (1994). "Normal cardiopulmonary responses during incremental exercise in 20-70-yr-old men". Med Sci Sport Exerc. 26 (5): 538–546. doi:10.1249/00005768-199405000-00003.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Gulati M, Shaw LJ, Thisted RA, Black HR, Bairey Merz CN, Arnsdorf MF (2010). "Heart rate response to exercise stress testing in asymptomatic women: the st. James women take heart project". Circulation. 122 (2): 130–37. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.939249. PMID 20585008.

- Wohlfart B, Farazdaghi GR (May 2003). "Reference values for the physical work capacity on a bicycle ergometer for men -- a comparison with a previous study on women". Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 23 (3): 166–70. doi:10.1046/j.1475-097X.2003.00491.x. PMID 12752560. S2CID 25560062.

- Farazdaghi GR, Wohlfart B (November 2001). "Reference values for the physical work capacity on a bicycle ergometer for women between 20 and 80 years of age". Clin Physiol. 21 (6): 682–87. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2281.2001.00373.x. PMID 11722475.

- Lounana J, Campion F, Noakes TD, Medelli J (2007). "Relationship between %HRmax, %HR reserve, %VO2max, and %VO2 reserve in elite cyclists". Med Sci Sports Exerc. 39 (2): 350–57. doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000246996.63976.5f. PMID 17277600.

- Karvonen MJ, Kentala E, Mustala O (1957). "The effects of training on heart rate; a longitudinal study". Ann Med Exp Biol Fenn. 35 (3): 307–15. PMID 13470504.

- Swain DP, Leutholtz BC, King ME, Haas LA, Branch JD (1998). "Relationship between % heart rate reserve and % VO2 reserve in treadmill exercise". Med Sci Sports Exerc. 30 (2): 318–21. doi:10.1097/00005768-199802000-00022. PMID 9502363.

- Karvonen J, Vuorimaa T (May 1988). "Heart rate and exercise intensity during sports activities. Practical application". Sports Medicine. 5 (5): 303–11. doi:10.2165/00007256-198805050-00002. PMID 3387734. S2CID 42982362.

- Zoladz, Jerzy A. (2018). Muscle and Exercise Physiology (first ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 9780128145937.

- Cole CR, Blackstone EH, Pashkow FJ, Snader CE, Lauer MS (1999). "Heart-rate recovery immediately after exercise as a predictor of mortality". N. Engl. J. Med. 341 (18): 1351–57. doi:10.1056/NEJM199910283411804. PMID 10536127.

- Froelicher, Victor; Myers, Jonathan (2006). Exercise and the Heart (fifth ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-4160-0311-3.

- Emren, Sadık Volkan; Gediz, Rahman Bilal; Şenöz, Oktay; Karagöz, Uğur; Şimşek, Ersin Çağrı; Levent, Fatih; Özdemir, Emre; Gürsoy, Mustafa Ozan; Nazli, Cem (February 2019). "Decreased heart rate recovery may predict a high SYNTAX score in patients with stable coronary artery disease". Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences. 19 (1): 109–115. doi:10.17305/bjbms.2019.3725. ISSN 1512-8601. PMC 6387669. PMID 30599115.

- OBGYN.net "Embryonic Heart Rates Compared in Assisted and Non-Assisted Pregnancies" Archived 2006-06-30 at the Wayback Machine

- Terry J. DuBose Sex, Heart Rate and Age Archived 2012-06-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Fuster, Wayne & O'Rouke 2001, pp. 824–29.

- Regulation of Human Heart Rate. Serendip. Retrieved on June 27, 2007.

- Salerno DM, Zanetti J (1991). "Seismocardiography for monitoring changes in left ventricular function during ischemia". Chest. 100 (4): 991–93. doi:10.1378/chest.100.4.991. PMID 1914618. S2CID 40190244.

- Puyo, Léo, Michel Paques, Mathias Fink, José-Alain Sahel, and Michael Atlan. "Waveform analysis of human retinal and choroidal blood flow with laser Doppler holography." Biomedical Optics Express 10, no. 10 (2019): 4942-4963.

- Guinness World Records 2004 (Bantam ed.). New York: Bantam Books. 2004. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-553-58712-8.

- "Slowest heart rate: Daniel Green breaks Guinness World Records record". World Record Academy. 29 November 2014.

- Fox K, Ford I (2008). "Heart rate as a prognostic risk factor in patients with coronary artery disease and left-ventricular systolic dysfunction (BEAUTIFUL): a subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trial". Lancet. 372 (6): 817–21. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61171-X. PMID 18757091. S2CID 6481363.

- Jiang X, Liu X, Wu S, Zhang GQ, Peng M, Wu Y, Zheng X, Ruan C, Zhang W (Jan 2015). "Metabolic syndrome is associated with and predicted by resting heart rate: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study". Heart. 101 (1): 44–9. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305685. PMID 25179964.

- Cook, Stéphane; Hess, Otto M. (2010-03-01). "Resting heart rate and cardiovascular events: time for a new crusade?". European Heart Journal. 31 (5): 517–19. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp484. ISSN 1522-9645. PMID 19933283.

- Cooney, Marie Therese; Vartiainen, Erkki; Laatikainen, Tiina; Laakitainen, Tinna; Juolevi, Anne; Dudina, Alexandra; Graham, Ian M. (2010-04-01). "Elevated resting heart rate is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease in healthy men and women". American Heart Journal. 159 (4): 612–19.e3. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2009.12.029. ISSN 1097-6744. PMID 20362720.

- Teodorescu, Carmen; Reinier, Kyndaron; Uy-Evanado, Audrey; Gunson, Karen; Jui, Jonathan; Chugh, Sumeet S. (2013-08-01). "Resting heart rate and risk of sudden cardiac death in the general population: influence of left ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart rate-modulating drugs". Heart Rhythm. 10 (8): 1153–58. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.05.009. ISSN 1556-3871. PMC 3765077. PMID 23680897.

- Jensen, Magnus Thorsten; Suadicani, Poul; Hein, Hans Ole; Gyntelberg, Finn (2013-06-01). "Elevated resting heart rate, physical fitness and all-cause mortality: a 16-year follow-up in the Copenhagen Male Study". Heart. 99 (12): 882–87. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303375. ISSN 1468-201X. PMC 3664385. PMID 23595657.

- Woodward, Mark; Webster, Ruth; Murakami, Yoshitaka; Barzi, Federica; Lam, Tai-Hing; Fang, Xianghua; Suh, Il; Batty, G. David; Huxley, Rachel (2014-06-01). "The association between resting heart rate, cardiovascular disease and mortality: evidence from 112,680 men and women in 12 cohorts". European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 21 (6): 719–26. doi:10.1177/2047487312452501. ISSN 2047-4881. PMID 22718796. S2CID 31791634.

- Arnold, J. Malcolm; Fitchett, David H.; Howlett, Jonathan G.; Lonn, Eva M.; Tardif, Jean-Claude (2008-05-01). "Resting heart rate: a modifiable prognostic indicator of cardiovascular risk and outcomes?". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 24 Suppl A: 3A–8A. doi:10.1016/s0828-282x(08)71019-5. ISSN 1916-7075. PMC 2787005. PMID 18437251.

- Nauman, Javaid (2012-06-12). "Why measure resting heart rate?". Tidsskrift for den Norske Lægeforening: Tidsskrift for Praktisk Medicin, Ny Række. 132 (11): 1314. doi:10.4045/tidsskr.12.0553. ISSN 0807-7096. PMID 22717845.

- Spodick, DH (1992). "Operational definition of normal sinus heart rate". Am J Cardiol. 69 (14): 1245–46. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(92)90947-W. PMID 1575201.

- Sloan, Richard P.; Shapiro, Peter A.; DeMeersman, Ronald E.; Bagiella, Emilia; Brondolo, Elizabeth N.; McKinley, Paula S.; Slavov, Iordan; Fang, Yixin; Myers, Michael M. (2009-05-01). "The effect of aerobic training and cardiac autonomic regulation in young adults". American Journal of Public Health. 99 (5): 921–28. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.133165. ISSN 1541-0048. PMC 2667843. PMID 19299682.

- Jenkins, David J. A.; Kendall, Cyril W. C.; Augustin, Livia S. A.; Mitchell, Sandra; Sahye-Pudaruth, Sandhya; Blanco Mejia, Sonia; Chiavaroli, Laura; Mirrahimi, Arash; Ireland, Christopher (2012-11-26). "Effect of legumes as part of a low glycemic index diet on glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial". Archives of Internal Medicine. 172 (21): 1653–60. doi:10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.70. ISSN 1538-3679. PMID 23089999.

- Hidayat K, Yang J, Zhang Z, Chen GC, Qin LQ, Eggersdorfer M, Zhang W (Jun 2018). "Effect of omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation on heart rate: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 72 (6): 805–817. doi:10.1038/s41430-017-0052-3. PMC 5988646. PMID 29284786.

- "Atrioventricular Block: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology". Medscape Reference. 2 July 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

References

- This article incorporates text from the CC-BY book: OpenStax College, Anatomy & Physiology. OpenStax CNX. 30 Jul 2014.